Painting your password on your face: Apple´s new Face ID and its implications on the security of its users.

On the 12th of September, Apple launched their new flagship model, the iPhone X. As usual, it was either met with oohs and aahs, or it was met with cynicism. This article will not focus on the price, design or whether Steve Jobs would have hated it, but will instead focus on a specific feature called ‘Face ID’, the successor of Apple’s Touch ID.

Facial scan

According to Professor Anil Jane, the simplest way of explaining this new feature is that “it compares two face images and determines how similar they are” (qtd. in Chamary “How Face ID Works On Apple’s IPhone X.”). This image is created by the combination of light projectors and sensors to create a full map of a person´s facial features. Apple calls this system the “TrueDepth camera system”.

As Apple throws around their buzzwords, such as Future, Revolution and Reinvention, it is hard not to get excited. However, the addition of using your face to access your phone has sparked up discussion again about the security of using biometrics to unlock your phone. An important question that should be asked is what this could mean for the secureness and privacy of its userbase. Another important question is whether the rising of biometrics is something to cherish and whether we even should strive to make traditional passwords obsolete.

This article will provide some explanation on how this new technology works. However, it will mainly focus on the implications that using biometrics to authenticate users may have on the security of those users. Furthermore, this article will attempt to assess what way of authentication provides the best security.

How it works and compares to Android

https://youtube.com/watch?v=njhlO2HSNz0

Apple presenting Face ID

Facial recognition on phones is nothing new, as the Galaxy S8 and Note 8 already provide their users with a way of unlocking their phone with their face. Nevertheless, it was cracked quickly, by using photos of the owner of the telephone. Therefore, Apple´s Face ID, even though it uses the same principles, is a whole new way of using facial recognition software. The iPhone X boasts some impressive hardware to make the facial recognition possible.

The hardware that makes Face ID work

The big difference between Android’s take on facial recognition and Apple’s, is that Apple uses a 3D-scan of the users face. It does so, by projecting more than 30,000 invisible dots on the users face and reads these dots with the help of an infrared camera. A flood illuminator also provides users with a way of scanning their face when it is dark. This is a completely new technology, at least in the smartphone industry.

Android phones do feature several biometrical scanners, for example, the Galaxy Note 8 has an iris scanner, fingerprint scanner and facial recognition (Haselton, par. 4). Apple has created a far more polished facial recognition feature, which is harder to hack than its Android counterpart, according to Apple. Furthermore, Apple confirmed that the software will adapt over time, which means that it is still possible to unlock your phone if you grow a beard or if you grow older, for example. Apple has set the bar for future phones with facial recognition, and other phone manufactures will surely follow in Apple’s footsteps. Something that also happened after the introduction of Touch ID.

Security concerns of using biometrics as authentication

Following a new feature like this, a debate about the secureness of Face ID has already been sparked. This debate created two fronts of yea-sayers and nay-sayers. Both fronts have stated some arguments to whether Face ID is secure or not. These arguments will be expounded upon below.

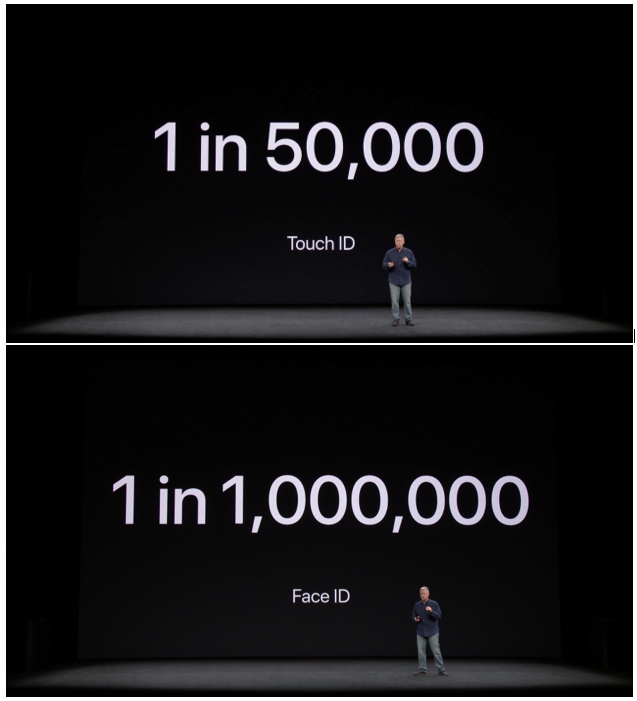

Apple proudly presenting the statistics

An argument in favour of the safety comes from Philip Schiller. During the presentation of Face ID, Schiller stated that the chance for someone to unlock your phone with their own fingerprint was around 1 in 50,000. He also stated that with Face ID, that same chance was 1 in 1,000,000. This was met with applause and even though these numbers may seem like a great improvement, according to Chamary, it is not relevant with regard to relative safety. He states that, unless the number of people is low (<100) it does not matter whether a random person could unlock it. Far more important is the chance that someone with nefarious intentions can unlock the phone. Adding to that point, a stolen password can be changed easily, while a stolen biometric is impossible to change. This means that it is risky to return to biometric authentication, once these biometrics are compromised (“No, Apple’s Face ID Is Not A ‘Secure Password”).

Another argument given in favour of Face ID is that with the introduction of Touch ID, the same concerns were raised. As Rene Ritchie states about Touch ID: “someone could wait for you to fall asleep, or incapacitate or restrain you, and then simply touch your finger to the sensor to unlock your phone.” (par. 13). Furthermore, it is possible to disable these biometric unlocks and just choose to go with a secure password. Users can assess whether they will choose convenience over security or the other way around. This however, assumes that consumers will be able to make the rational decision of choosing security over convenience.

According to Clarke and Furnell, mobile users are indeed security conscious, but when faced with a choice between security and convenience, show an inclination to choose for convenience (521). Choosing convenience over privacy was also tested by Anne Yaus, whose study also proved that consumers of technology are more inclined to value convenience over security and privacy (68).

Biometrics versus traditional passwords

The usage of biometrics versus the use of traditional passwords has been a debate since biometric authentication first came to light. There are upsides and downsides to using biometrics compared to traditional passwords, for example, biometrics cannot be lost. Furthermore, they are difficult to steal or forge, however it is not impossible and has happened before (Ratha, Connel and Bolle 633) .

According to Ratha, Connel, and Bolle, the greatest strength of biometrics is also its greatest liability. The fact that biometrical data does not change over time makes is so that once it has been compromised, it is compromised forever, as stated earlier in this text (633).

Even though Clarke and Furnell state that using biometrics could be an appropriate means of improving security (526). This does not necessarily prove to be true. Using biometrics may be better than only providing a password in certain situations where users use poorly chosen passwords. Unfortunately, studies show that people often choose trivial passwords, which are not changed frequently (Summers and Bosworth 2) or do not take passwords seriously (Cole 285).

Furthermore, biometrics are not flawless, just like passwords. This is confirmed by, Tom Grissen, CEO of biometrics firm Daon who has stated that, Face ID is more secure than Touch ID and/or badly chosen passwords. However, he also stated: “None of these systems are flawless. And you’ll see it with Apple. They can be defeated. Somebody will do that” (qtd. in Lovelace).

Why not both?

No matter how good biometric technology or passwords can get, one single authentication tool will most likely not be enough to provide strong protection. Biometrics can be used to further improve security by using biometrics and traditional passwords conjunctively (Jackson). This seems like the most secure solution, but will have some effect on the user’s convenience.

Adding traditional passwords on top of biometrics also provides users with more robust security in some cases. For example, traditional passwords can offer more safety against law enforcement unlocking the device against the will of the owner (Lomas).

In 2016 a warrant was issued that let LAPD cops unlock an iPhone with the owner’s fingerprints. This is a case where biometrical information was forcibly used by law enforcement. This was a direct consequence of a ruling in 2014, where a judge declared that it was illegal to force someone to hand over their password, but not illegal to forcibly make someone hand over biometrical information (LaPlante).

It is hard to say if it will be possible for law enforcement to make use of this ruling easily, however it does create a greater need for traditional passwords. Considering this, Apple has announced that there will be a way to disable Face ID and Touch ID (for the earlier models) by pressing the home button five times in quick succession. This brings up a second screen where the phone can only be unlocked with a long, complex password, making it impossible for law enforcement to open it without the password (Buhr).

Lastly, to ensure that the data is not used for other purposes than authenticating the user, it is crucial that biometrics are stored locally on the device instead of in a database. Data stored locally after encryption is safer than storing it in a database after all. Fortunately, Apple already confirmed to store Face ID data locally on the devices, and also confirmed they will not be able to access it (Glaser).

What now?

Apple´s Face ID has provided us with a more advanced facial recognition software that is sure to set the bar for future smartphones. Even though this feat should not be underestimated, the implications on the security of its users should not be taken lightly.

Using biometrics to unlock a phone has become a staple in the smartphone industry, where users choose convenience over security. Concerns about the security of these biometrics have been stated before and were also prevalent when fingerprint scanners were first released.

It is too soon to say whether Face ID will be as safe as Apple claims it to be or if it will unleash a plethora of problems, however its secureness should remain a point of discussion. In an ideal world users would use both a traditional password, as well as their biometrics to unlock the phone. This would provide the strongest protection against infringement of people’s privacy.

Luckily Apple has already announced that there will be a way to quickly disable Face ID (and Touch ID) on iOS 11. With this feature a password is needed to unlock the phone and if the password is strong enough, it may provide some extra protection when it is needed.

Unfortunately, as we all know, people will most likely choose convenience over security and will choose for the least annoying way to unlock their phone, even if they must sacrifice a big chunk of their security for it.

References:

Apple. Face ID hardware, Apple, 12 September 2017, <https://www.apple.com/iphone-x/#face-id>.

Buhr, Sarah. “An IOS 11 Feature Could Let You Quickly Disable TouchID and Keep Cops Out.” TechCrunch, 17 August 2017, <techcrunch.com/2017/08/17/an-ios-11-feature-could-let-you-quickly-disable-touchid-and-keep-cops-out/>.

Chamary, JV. “How Face ID Works On Apple’s IPhone X.” Forbes, Forbes Magazine, 16 September 2017, <www.forbes.com/sites/jvchamary/2017/09/16/how-face-id-works-apple-iphone-x/>.

——— “No, Apple’s Face ID Is Not A ‘Secure Password’.” Forbes, Forbes Magazine, 18 September 2017, <www.forbes.com/sites/jvchamary/2017/09/18/security-apple-face-id-iphone-x/>.

Clarke, Nathan L., and Steven M. Furnell. “Authentication of users on mobile telephones–A survey of attitudes and practices.” Computers & Security 24.7 (2005): 519-527.

Cole, Eric. Hackers beware. Carmel: Sams Publishing, 2002.

Glaser, April. “You’ll Love Unlocking Your IPhone X With Your Face. So Will Police Trying to Access It.” Slate Magazine, 12 September 2017, <www.slate.com/blogs/future_tense/2017/09/12/the_iphone_x_s_face_id_is_a_major_privacy_concern.html>.

Grossman, Lev. “Apple CEO Tim Cook: Inside His Fight With the FBI.” Time, Time, 17 Mar. 2016, <time.com/4262480/tim-cook-apple-fbi-2/>.

“Facial Recognition on Samsung’s New Phone Has Already Been Cracked.” Naked Security, Sophos, 3 Apr. 2017, <nakedsecurity.sophos.com/2017/04/03/facial-recognition-on-samsungs-new-phone-has-already-been-cracked/>.

Haselton, Todd. “Here’s How the IPhone X Compares to the Galaxy Note 8.” CNBC, NBCUniversal, 18 September 2017, <www.cnbc.com/2017/09/16/iphone-x-vs-galaxy-note-8-comparing-features.html>.

Jackson, William. “Passwords vs. Biometrics.” GCN, 1105 Media, Inc., 19 September 2017, <gcn.com/blogs/cybereye/2014/09/passwords-vs-biometrics.aspx>.

LaPlante, Alice. “CenturyLinkVoice: 4 Ways To Stop Hackers From Invading Your Connected Home.” Forbes, Forbes Magazine, 13 September 2017, <www.forbes.com/sites/centurylink/2017/09/13/4-ways-to-stop-hackers-from-invading-your-connected-home/>.

Lomas, Natasha. “IPhone X’s Face ID Raises Security and Privacy Questions.” TechCrunch, TechCrunch, 13 September 2017, <techcrunch.com/2017/09/13/iphone-xs-face-id-raises-security-and-privacy-questions/>.

Lovelace, Berkeley. “Apple’s Face ID Isn’t Flawless — Technology Can and Will Be Hacked, Cybersecurity Expert Says.” CNBC, CNBC, 15 September 2017, <www.cnbc.com/2017/09/15/apples-face-id-isnt-flawless–tech-can-and-will-be-hacked-expert.html>.

Ratha, Nalini, et al. “Cancelable biometrics: A case study in fingerprints.” Pattern Recognition 4. (2006): 519-527.

Ritchie, Rene. “Face ID: Why You Shouldn’t Be Worried about IPhone X Unlock.” IMore, IMore, 13 September 2017, <www.imore.com/face-id>.

Sabena, Fathimath, Ali Dehghantanha, and Andrew P. Seddon. “A review of vulnerabilities in identity management using biometrics.” Future Networks 2010. (2010): 42-49.

Summers, Wayne C., and Edward Bosworth. “Password policy: the good, the bad, and the ugly.” Proceedings of the winter international synposium on Information and communication technologies. (2004). Trinity College Dublin.

Yau, Anne. “Measuring Levels of Privacy Concern: Context and Trade-offs Between Competing Desires.” PACIS 2007 Proceedings (2007): 72.