The fake fame – Black market on social media

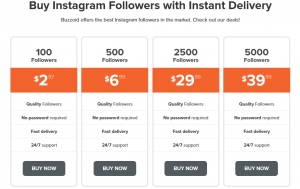

Sitting on a Saturday morning at my desk, it took me ten seconds to find a website which wanted to sell me 2,500 ‘quality Instagram followers’ to boost my account for the price of about 25€. The website claims with being the fastest, cheapest and best Instagram service on the Internet (Buzzoid). Buying ‘Instagram-fame’ sounds tempting, especially in a period where the term ‘Influencer-Marketing’ is mentioned in nearly every marketing conference.

I would not be the first, because many public figures and brands are known to boost their social media accounts with fake followers and so-called bots which enrich their account with likes and interaction. During his US election campaign in 2012, the Twitter account of candidate Mitt Romney experienced an abrupt increase of followers in a short period of time. Later the majority turned out to be fake (Considine). Also the US election in 2016 was not free of bots and resulting scandals (Bessi and Ferrara).

To be honest it is comprehensible why people or companies buy followers and likes. Social media channels are not only a good opportunity to build and maintain the customer relationship, they also become an important channel of distribution. It is an open secret that brands pay massive amounts to social influencers in return for promoting their product. Therefore it is obvious that more follower means more potential costumers which can result in larger payments.

If this is not enough, the internet community goes one step further: Verification badges are sold illegally for massive sums. While Twitter and Facebook make it possible to apply for a verification, Instagram has strict rules to assign the verified badge. But what is this blue crest with a white tick really about? The verification badge has become something of a status symbol across social media. It is “a sign that the person is real, trustworthy and, in the case of Instagram’s influencer network, a way to make your account an ideal candidate for brands to use for advertising” (Charlton).

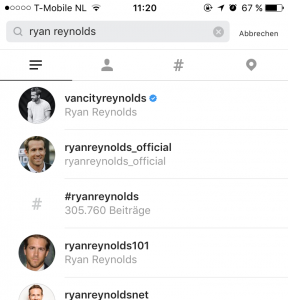

Verified accounts are more likely to show up in search results and get more attention on Instagram. We know that attention is the currency on social media. Therefore brands will pay more for posts by these accounts. In addition, brands who have a verification tick, seem to be trustworthy and established. To come to the point: Verification allows for attention and attention means money. Where you can make money, there are always people who try anything to make more out of it (Cox).

Now, a digital black market for these verification badges has been uncovered. According to the digital media website Mashable, you can get a verification tick via a middleman in the black market – the fees range from the price of a bottle of wine to 12,000€. A contact working inside Instagram charges 1,000€ per verification and grants the blue checkmark. The middleman charges whatever he likes, depending on the needs and the resources of his verification-clients (Flynn).

Now, a digital black market for these verification badges has been uncovered. According to the digital media website Mashable, you can get a verification tick via a middleman in the black market – the fees range from the price of a bottle of wine to 12,000€. A contact working inside Instagram charges 1,000€ per verification and grants the blue checkmark. The middleman charges whatever he likes, depending on the needs and the resources of his verification-clients (Flynn).

It seems to be unethical, dishonest and even illegal, but why is it not possible on Instagram to apply for a verification? On their website Instagram claims to only allocating them to selective “public figures, celebrities and brands” (Instagram). Perhaps they challenge it and transform the simple certification in a sought-after source of fame and money. In the influencer community the black market is an open secret – Instagram declined any comment on this.

There are also some voices that declare oneself in favour of buying the blue tick. The price of several thousand Euro for a simple badge is heavy, but compared with advertising on media as billboards, print or TV let one reconsider this investment. The advertising standards has transformed to social media where other rules supply (Wells). For some people or brands it help to get their foot in the door and raise a stabile follower base.

It reminds of the Utilitarianism theory formulated by the philosopher John Stuart Mill in the middle of the nineteenth century. It focuses on the results or consequences of our actions and treats intentions as irrelevant. Therefore, good consequences equals good actions – with happiness as our final end (Mill). According to that hypothesis, the term ‘fake it ‘till you make it’ is seen in a new, more valuable light. You never get a second chance for the first impression. In the digital word this impression is characterised by the number of followers or even a little blue tick next to the name. Generating these fakes on social networks can be used to gain quick recognition and also to increase the reputation in the market. Fake tools can improve the visual identity and make the naïve audience thinking that the person or brand is real and currently trending (Rastogi 3).

Regarding the ethics of transparency in the social web, such behaviour seems unethical and immoral. Laughlin claims that “the argument that high-octane deception is acceptable because it’s a feature of commerce, and commerce is good, cuts very little ice when the house one just bought is found to be infested with termites” (259). However, deception is perfectly natural behaviour of humans (Kornet). Laughlin sees the problem of false electronic communication, which is going beyond fake followers, not in the failure of people’s self-control, but rather in the “failure of regulatory machinery designed by nature to prevent people from doing selfish things that they want to do but shouldn’t because those things are hurtful to everyone else”(259). Therefore the solution is not a falsehood-detecting robot, because truth and false are economic concepts, not objectives, which makes it impossible to distinguished them by mechanical methods. The key is, as Laughlin says, the principle of witness where people being observe and knowing to be observed with the aim to create correct behaviour (259).

Regarding the ethics of transparency in the social web, such behaviour seems unethical and immoral. Laughlin claims that “the argument that high-octane deception is acceptable because it’s a feature of commerce, and commerce is good, cuts very little ice when the house one just bought is found to be infested with termites” (259). However, deception is perfectly natural behaviour of humans (Kornet). Laughlin sees the problem of false electronic communication, which is going beyond fake followers, not in the failure of people’s self-control, but rather in the “failure of regulatory machinery designed by nature to prevent people from doing selfish things that they want to do but shouldn’t because those things are hurtful to everyone else”(259). Therefore the solution is not a falsehood-detecting robot, because truth and false are economic concepts, not objectives, which makes it impossible to distinguished them by mechanical methods. The key is, as Laughlin says, the principle of witness where people being observe and knowing to be observed with the aim to create correct behaviour (259).

On the contrary, Alves de Lima and Berente think that social bots that behave unethically for example with spreading misinformation in form of ‘fake news’, could be controlled by other social bots which ferret out such deceitful activity. It is important to distinguish between bots with good and bad behaviour. There are many social bots that inhabiting social network platforms that are useful and help people for instance to lead people to socially interaction and infuse them with social feelings (Bakardjieva 244).

However, this is no reason to understate the growing malicious variety of social bots as for example “fraudulent accounts [as] automatically generated credentials used to disseminate scams, phishing, and malware” (Chris et al. 1). A few years ago Chris et al. uncovered a commercial ecosystem in the form of an underground market for automated Twitter accounts. According to that, at least 3% of active Twitter accounts are fraudulent – and this was only in 2011 (Chris et al. 1). A recent study from the Davis et al. estimate the percentage of social bots on Twitter between 9% and 15% (1). It is not surprising that there already exist a large number of studies to identify these malicious bots. The mentioned study from Chris et al. presented a framework for bot detection on Twitter with a machine learning system (1).

To come back to the marketing and advertising industry on the social networks, there are many ways to find out if an account is boosted with fake followers. For example with simple websites and apps that allows everyone to make the ‘fake check’ (Ibex). Sometimes a brief glance at the follower interaction or even some follower-profiles shows if the account has many fake followers.

Unsurprisingly, I could not make the transaction and really boost my account with the view to become ‘Instagram-famous’. Buying my own followers speak against my ethics and is morally dishonest in my view. Moreover, it is possibly dangerous and can tear down trust people have in companies and public figures. “Buying followers is the easy route, but it’s like cheating during your favorite board game: you’re likely to be labeled a fraud and a cheat than win like you wanted to” (Hockenson). But that does not mean that it discourage everyone, because there are always cheaters.

References

Alves de Lima, Carolina, and Nicholas Berente. “Is That Social Bot Behaving Unethically?” Communication of the ACM, vol. 60, no. 9, pp. 29–31. cacm.acm.org/magazines/2017/9/220438-is-that-social-bot-behaving-unethically/fulltext.

Bakardjieva, Maria. “Rationalizing Sociality: An Unfinished Script for Socialbots.” The Information Society, vol. 31, no. 3, 2015, pp. 244–56. www-tandfonline-com.proxy.uba.uva.nl/doi/full/10.1080/01972243.2015.1020197.

Bessi, Alessandro, and Emilio Ferrara. Social bots disort the 2016 U.S. Presidential election online discussion. 24 Oct. 2016, firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/7090/5653.

Buzzoid. Buy Instagram Followers. 2017, buzzoid.com/buy-instagram-followers/.

Charlton, Alistair. There is a black market charging $15,000 for Instagram verification. 4 Sep. 2017, www.ibtimes.co.uk/there-black-market-charging-15000-instagram-verification-1637851.

Chris, et al. “Trafficking Fraudulent Accounts: The Role of the Underground Market in Twitter Spam and Abuse.” 22nd USENIX Security Symposium: Aug. 14 – 16, 2013, Washington, D. C, edited by Sam King, USENIX Association, 2013, pp. 195–210.

Considine, Austin. “Buying Their Way to Twitter Fame.” The New York Times, 22 Aug. 2012, www.nytimes.com/2012/08/23/fashion/twitter-followers-for-sale.html?smid=pl-share.

cox, Kate. How Much Is Instagram Verification Worth On The Black Market? 1 Sep. 2017, consumerist.com/2017/09/01/how-much-is-instagram-verification-worth-on-the-black-market/.

Davis, Clayton A., et al. Online Human-Bot Interactions: Detection, Estimation, and Characterization. Center for Complex Networks and Systems Research, 2017, arxiv.org/pdf/1703.03107.pdf.

Flynn, Kerry. Inside the black market where people pay thousands of dollars for Instagram verification. 1 Sep. 2017, mashable.com/2017/09/01/instagram-verification-paid-black-market-facebook/.

Hockenson, Lauren. Buy Twitter followers: An easy game, but not worth the risk. 2012, thenextweb.com/twitter/2012/12/15/fake-followers-an-easy-game-but-not-worth-the-risk/.

Ibex, Ashlee. Buying Fake Twitter Followers: Is It Worth It? 2014, www.brandba.se/blog/2014/4/17/fakefollower.

Instagram. Instagram-Help. 2014, help.instagram.com/854227311295302.

Kornet, A. “The truth about lying.” Psychology Today., 2012,

Laughlin, Robert B. “Truth Telling and Deception in the Internet Society.” Transparency in social media: Tools, methods and algorithms for mediating online interactions, edited by Sorin Adam Matei et al., Springer, 2015, pp. 257–75. Computational Social Sciences.

Mill, John Stuart. Utilitarianism. 4th ed., Harvard University, 1871.

Rastogi, Tushti. A Power Law Approach to Estimating Fake Social Network Accounts. 2016, arxiv.org/ftp/arxiv/papers/1605/1605.07984.pdf.

Wells, Ione. Is paying for Instagram verification really such a terrible thing? 15 Sep. 2017, metro.co.uk/2017/09/15/is-paying-for-instagram-verification-really-such-a-terrible-thing-6931097/.