Facial ID scanning: An advertisers’ dream, or a consumers’ nightmare?

A couple of weeks ago, a traveler noticed a camera in one of the digital advertising screens at a train station in the Netherlands. A photo of this ‘hidden’ camera was then posted on Twitter, questioning the purpose of these camera’s. What is this way of advertising and how come this is triggering such a shocked response by consumers?

https://twitter.com/Nsdefect/status/904582967409987585

Translation: “@NS_online @ROVER_online what are these mini-camera’s doing in the advertising screens!

This does not look like surveillance to me! Train station Amersfoort platform 6/7″

This discovery lead to a lot of fuss and frustrations on the platform and has re-opened a national discussion on privacy in diverse media. People are worried about being recorded by the advertising screens for other causes than surveillance and they are concerned about their privacy. What are these camera’s doing? Is Big Brother really watching us?

It turned out that not Big Brother, but advertising company Exterion – the owner of these screens – was watching us. These ‘hidden’ camera’s are not recording, but they are equipped with special sensors that are used to collect metadata about the performance of the showcased ads. By taking facial ID scans of trespassers, the sensor can measure several things about them, for instance, if they look at the ad and for how long. This is very useful information for advertisers and can help them to improve their content.

How does it work?

The automated facial coding software that is used for these scans is called VidiPort and is owned by the international company Quividi. Quividi offers Application Programming Interfaces (API’s) which is a code that allows other computer programs to access services offered by an application (Manovich 16).

Quividi provides two main sets of API’s for this kind of data-collection.

As explained on their website:

1. The Real-Time API works from within VidiReports and makes it possible to get a live reading on each single tracked watcher in a scenery. Up to 10 times per second, the position, distance, gender, age, mood, attentive state and other variables are made available, either on a TCP socket or a Websocket.

2. The Cloud API works from within VidiCenter and provides raw or aggregated audience data and information on the video sensors. The Cloud API is intended to help build custom made reports and dashboards.

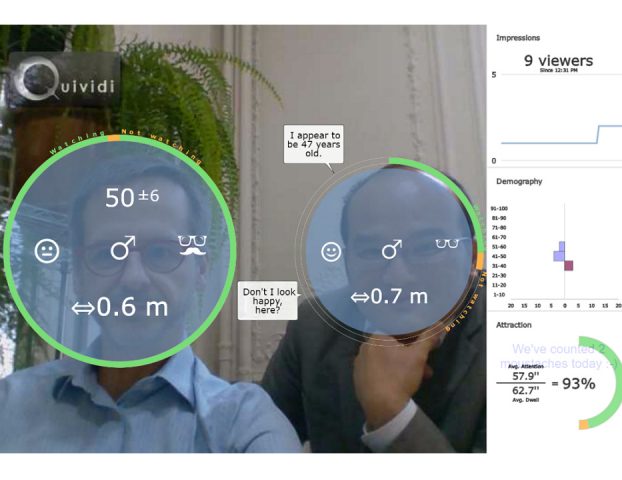

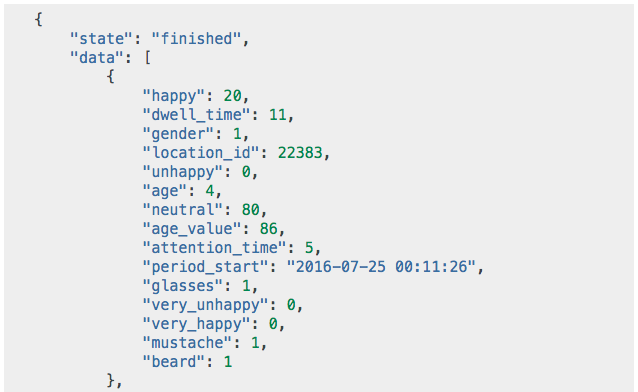

The ‘live reading’ through facial ID scanning by the VidiReports API looks as follows:

As you can see, several features can be recognized by the system based off the face scan. The computer system then translates these video findings into a code and transfers it to a database. This database is what will be visible after the processing of the scans and what the ad(vertiser) can act upon.

Yet, unlike in the extensive database-example above, Exterion claims to only track age, gender and watching period. They don’t track moods for example.

Facing privacy issues

Quividi declares not to use face recognition but face detection and therefore cannot recognize any individuals. They do not record people, they just count numbers so to say.

Important to know is that the program does not save any of the video footage after it’s being processed into code, and it is only this coded database that is accessible for use. Because of this protocol, the code can never be traced back to the individual personal scans.

As Quividi writes on the privacy section on their website:

“Quividi does not collect or record any image or video, it only collects the anonymous “metadata” that describes the size and the demographics of an audience. As soon as our video processing solution processes an image, the image is immediately ‘forgotten’ by the software.”

Because no personal data is stored, Quividi and Exterion claim that what they do is completely legal.

What about personal data?

However, when personal data is not stored does not mean that it’s not processed. In fact, Quividi literally speaks of “processing images”. When personal data is processed, it has once been possible to identify a consumer and thus should be considered as personal data and has to be treated as such (Lewinski et al. 736). This realization is important because the Dutch Privacy Law states that: “The processing of any personal data in the Netherlands requires the data subject’s unambiguous consent”. Since it appears impossible to use automated facial coding software without processing personal data, users of this software have to comply with the privacy rules on data protection (Lewinski et al. 740).

The problem here lies in the “data subject’s unambiguous consent”. Because the collecting – and processing – of all this data has been carried out without consumers knowing it and thus without their permission. Exterion hasn’t let the trespassers know, yet asked them, that their faces were being scanned for the sake of data collection for advertising purposes.

One could thus argue that the processing of personal data is not the only questionable topic here. The bigger issue actually lies in the lack of clear communication on behalf of the advertising company and in the absence of ways to validate consumers’ permission for the processing of their personal data.

Transparency is key

One of the biggest concerns consumers have with regards to privacy, is transparency and their levels of awareness in the collection and dissemination of personal data (Rapp et al. 51). Given this, in combination with the Dutch Privacy Law makes it hard not to see the use of ‘hidden’ face scanners as rather remarkable to say the least. If your consumer’s biggest concern is transparency, this should be the first topic ticked off the checklist.

Exterion did acknowledge their lack of transparency in an official statement on their website after the commotion:

“We regret that this discussion has emerged due to our lack of clear communication on what it is we exactly measure… It was never our purpose to cause any commotion.”

In response to all the outrage and negativity, Exterion has declared to switch off all the sensors for now. Consumers often have little to no control in these decisions (Lewinsky et al. 740). This is why there is an obligation of companies to comply to (Privacy) Laws but the compliance of these companies to (Privacy) Laws, it protects consumers and gives them back some power. The Autoriteit Persoonsgegevens (Dutch authority of personal information) has announced to further investigate the use of such sensors.

Consumer control

In their personal online interface, consumers can be offered two methods to control the unforeseen use of personal data: opt-in and opt-out (Fletcher 260). Opt-in gives consumers the opportunity to actively register before they receive direct marketing messages whereas opt-out means that the consumer is responsible for his own prevention of receiving these direct messages (260). The Exterion advertising screens however, are situated in extremely public spaces such as railway stations and shopping streets. This makes it almost impossible for consumers to avoid these screens if they wanted to. Opt-in possibilities are not very feasible in the offline world and since these advertising screens are in the public sphere there simply is no way to opt-out. This makes it impossible to give people the control over what they want to engage in or not.

People feel comfortable when they have a sense of self-determination through autonomy and the right to privacy is an extension of that (McStay 601). However this lack of control leads to reduced confidence (Fletcher 260) which can explain the online outrage and frustration.

We live in a world where new technologies and new features develop exponentially, but if transparency and honesty on the developers’ side are not developing accordingly, it’s hard for citizens to adapt to these technologies. The use of facial ID scans in an advertisement environment clearly needs some more explanation for consumers in order to be able to adapt to it. It is argued that when companies are more open about their intentions and be transparent about their data-processing, this can be beneficial for both advertisers and consumers in terms of trust (McStay 609). The best ethical way would be to provide truly opt-in approaches to consent in order to provide autonomy for the consumers (609). However this is difficult to carry out, since the public sphere makes it hard to ask consumers for permission.

An Exterion screen with a covered sensor.

Advertising companies should have a remarkable sense of responsibility in the privacy debate since they are the ones on the operating side. Therefore they should ensure a clear understanding of their new ways of working in the digital age to their consumers to remain trust and avoid commotion. It is mostly their task to seek for new and suitable ways of asking for consent and providing consumers with the most transparent environment.

Nevertheless, consumers now have adapted their own ways of opting-out for the time being, by demonstratively covering the Exterion screen-sensors with stickers. This is their way of letting the big boys know that they don’t thoughtlessly approve this kind of data collection. They are not ready for it, or at least not in this sneaky non-transparent way. Exterion has found out the hard way they shouldn’t mess with their audience and that the offline power of the community cannot be taken away so easily.

A sticker-covered Exterion camera.

References

Fletcher, Keith. “Consumer Power and Privacy: the Changing Nature of CRM.” International Journal of Advertising 22.2 (2003): 249-272.

Lewinski, Peter, Jan Trzaskowski, and Joasia Luzak. “Face and Emotion Recognition on Commercial Property under EU Data Protection Law.” Psychology & Marketing 33.9 (2016): 729-746.

Library of Congress. 2012. Wendy Zeldin. 19 September 2017. <www.loc.gov/law/help/online-privacy-law/netherlands.php>.

Manovich, Lev. Software Takes Command. Vol. 5. A&C Black, 2013.

McStay, Andrew. “I Consent: An analysis of the Cookie Directive and its Implications for UK Behavioral Advertising.” New Media & Society15.4 (2013): 596-611.

@NSdefect. “@NS_online @ROVER_online wat doen die mini-cameratjes in die reclamezuil! Dit lijkt me geen beveiliging! Station amersfoort perron 6/7.” Twitter, 3 Sept. 2017, 10:52 p.m., <twitter.com/Nsdefect/status/904582967409987585/photo/1?>.

Online Privacy Law: Netherlands. 23 Sept. 2017, <www.loc.gov/law/help/online-privacy-law/netherlands.php.>.

Rapp, Justine, et al. “Advertising and Consumer Privacy.” Journal of Advertising 38.4 (2009): 51-61.

Privacy. 2017. Quividi. 22 Sept. 2017, <www.quividi.com/privacy/>.

Products & Services. 2017. Quividi. 22 Sept. 2017, <www.quividi.com/products-services/>.

Sondermeijer, Vincent. “Exploitant Schakelt Cameras In Reclamezuilen Uit”. NRC.nl. 2017. NRC Handelsblad. 19 September 2017. <http://www.nrc.nl/nieuws/2017/09/11/exploitant-schakelt-cameras-in-reclamezuilen-uit-a1573012>.

Sondermeijer, Vincent. “Reclamezuilen Filmen Reizigers Op NS Stations”. NRC.nl. 2017. NRC Handelsblad. 4 September 2017. <http://www.nrc.nl/nieuws/2017/09/11/exploitant-schakelt-cameras-in-reclamezuilen-uit-a1573012>.

Versluis, Els. “An Exterion Screen with Covered Sensor.” 2017. JPEG file.

Versluis, Els. “A Sticker-Covered Exterion Camera.” 2017. JPEG file.