What Apple’s new cookie blocker says about platforms and privacy

Apple’s new built-in cookie blocker may be welcomed by most consumers, but what does it say about the power yielded by the company, which maintains vast amounts of data on its own users? If platforms are allowed to make one decision affecting the usership of their technology, such as blocking certain ads or information, what level of control or visibility should be expected?

Last week, the latest version of Apple’s operating system, iOS 11, went live for installation on iPhones and iPads globally.

Before the upgrade hit any users’ devices however, it had already provoked criticism from an unlikely source – digital advertisers.

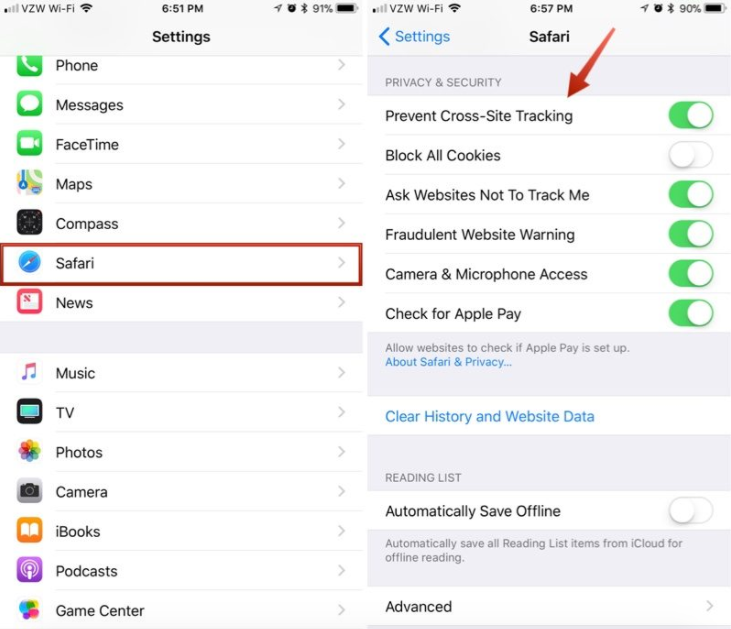

The complaints lie with the news that iOS 11 integrates cookie-blocking technology into the Safari browser for the first time. Dubbed ‘intelligent tracking prevention’, the default feature overrides third party cookie preferences with a series of Apple-controlled benchmarks.

Third-party sites are allowed to track Safari users for 24 hours, but after that, the cookies can only be used for log-ins, meaning that advertisers won’t be able to track conversions and sales that happen after that time. The technology is expected to be made available on Apple computers later this month.

Apple’s new ‘intelligent tracking prevention’ in iOS 11 settings.

The new feature isn’t an ad-blocker – the same volume of ads will still show up for users as normal. What changes is the degree of personalisation that the advertiser will be able to serve up to individual users. Digital advertisers use cookie technology to ‘follow’ users around the web by retargeting ads based on products or services the user has previously expressed interest in.

By signalling its intent to block advertisers’ ability to track the behaviour of Safari users, Apple had cast an obstacle in the path of their complainants’ business model. Digital marketers claim that giving iPhone users the ability to opt out of this tracking greatly reduces the ability to serve more effective ads.

The Guardian described the move as causing ‘unprecedented disruption’ for internet advertisers (Hern). A coalition of leading advertising groups including the American Association of Advertising Agencies, the Association of National Advertisers, and the Data & Marketing Association amongst others, released an open letter claiming that Apple threatened to ‘“sabotage” the economic model of the internet’ (Swant).

Of course, third-party ad-blocking technology is already widespread. Industry research group eMarketer estimates that 27.5% of US internet users will block ads in 2017 (eMarketer Scales Back Estimates). But Apple’s decision, while still allowing de-personalised ads, differs greatly in its potential scale and reach.

The most significant difference between ad-blocking technology, from providers like AdBlock Plus and Brave Browser, and Apple’s cookie blocker lies in implementation. AdBlock Plus users firstly need be aware of the technology, and then take steps to install the browser plug-in. Apple’s ‘intelligent tracking prevention’ meanwhile is already on, by default, for any iOS user that upgrades their operating system.

Built-in cookie blockers like Apple’s ‘intelligent tracking prevention’ are not yet mainstream in mobile devices and browsers, but this is a trend that appears to be gathering impetus amongst platforms and other digital infrastructure providers.

For instance, Google is also in the midst of a campaign to neutralise what it sees as the ill-effects of digital advertising on its Chrome browser. This month the search giant revealed it will no longer autoplay content with sound from January 2018, in order to make the format ‘more consistent with user expectations’ (Unified Autoplay). In June, the platform announced that it would stop showing ads that are not compliant with an agreed code (the ‘Better Ads Standard’) from early 2018. In a communiqué titled ‘Building a better web for everyone’, Google Senior VP for Ads & Commerce, Sridhar Ramaswamy, wrote “Chrome has always focused on giving you the best possible experience browsing the web… We believe these changes will ensure all content creators, big and small, can continue to have a sustainable way to fund their work with online advertising.”

What is notable in Google’s plans ad-block plans for Chrome is that ads which do meet a standard set by the ‘Coalition for Better Ads’, a group made up of publishers, advertisers and, critically, platforms including Facebook and Google, are unaffected. These two platforms together are expected to collect around half of total internet advertising spend globally this year, reaching billions of people. It can therefore be argued that these platforms have an outsized role in dictating the outcome of the coalition’s suggestions.

For online advertisers, eye-catching autoplay videos, pop-ups and other tactics are all part of the game of attention harvesting. Many digital publishers such news and entertainment sites rely on the placement of these ads as part of their business models. (Gomer et al, 549).

Apple and digital platforms such as Facebook, Instagram and Google, however, see user experience as critical. Users must be enticed to stay within the walls of the platform for as long as possible, and encouraged to return regularly. In an interview with Ad Age in 2012, Facebook’s head of consumer marketing Rebecca Van Dyck linked the platform with the innate human desire to connect. Dyck said, “We make the tools and services that allow people to feel human, get together, open up. Even if it’s a small gesture, or a grand notion — we wanted to express that huge range of connectivity and how we interact with each other” (Lee, 28).

Too many irritating experiences with intrusive advertising lessens that desire to connect, and risks negatively impacting platforms’ all-important monthly active users metric.

If adopted unilaterally, these changes have the potential to force significant changes in how online advertising is conducted, and consequently, how a large part of the economic model of the web operates. This leaves the platforms and other internet infrastructure gatekeepers like Apple with the potential to make decisions about what kind of ads and potentially other information are ‘suitable’ for their users, raising questions about how platforms may use such precedents in the context of information distribution more generally.

For its part, Apple claimed it only had the general population’s best interests in mind with the cookie blocker. “Apple believes that people have a right to privacy… Ad tracking technology has become so pervasive that it is possible for ad tracking companies to recreate the majority of a person’s web browsing history,” read a statement issued by the company in wake of the backlash (Dalrymple).

Apple’s new iPhone X

But Safari users assuming that the new measures would ensure that their online privacy would be protected in perpetuity would be misled. Apple itself already has comprehensive tracking information on its users. For most iPhone users, a visit to the privacy settings section of their phone can be an eye-opening experience. iOS 10 can track where users parked their car, send location-based ads and alerts, scan private messages and emails for dates and times to automatically create event reminders, and more (Thomas).

Sometimes, smartphone users see the use of this ‘owned’ personal data as being more invasive than the targeted ads themselves. In a 2011 experiment, researchers designed a survey to see how users valued various aspects of their smartphone privacy. Offered the option of paying 99 cent for an ad-free app, 77.7% of respondents said they would rather get the free version, which featured targeted advertisements. In the same survey, the researchers found that ‘participants were significantly more concerned over the use of address book data’ on their phones (Egelman, Felt and Wagner, pg 232).

The Apple case isn’t the first example of a major digital infrastructure provider making a policy or regulatory decision with the potential to impact hundreds of millions of people, in the name of doing what is right for the ‘consumer’. Other software giants have demonstrated similar willingness to take vigorous measures in changing user experience or system features to safeguard their usership.

Like Apple, Google also already has extremely extensive tracking information on its users, across multiple devices. Until June 2017, Google scanned the contents of non-paying Gmail users in order to deliver more targeted ads to users (Greene).

It’s certain that the accumulation of user data collected by the likes of Apple and Google could potentially be used for alternative purposes, in areas of government and wider societal issues. Discussing big data in his book ‘The Data Revolution’, Rob Kitchin describes the potential uses of such information for causes beyond any one company’s financial interests, to “help address some of the most pressing social, political, economic and environmental issues facing the planet” (79).

The cookie-blocking dispute pits two usually complimentary commercial interests against each other: a software and hardware provider in Apple, and the digital marketing industry on the other. In the regular course of things, Apple provide the infrastructure with which to reach custom segments of the population, which digital advertisers pay for. It seems likely that we’re set to see more of these types of conflicts emerge between the ‘infrastructure’ set, and other interests dependent on platforms to reach audiences.

This raises the question of who, ultimately, is looking after the interests of the internet public. What is clear is that there are a multitude of actors involved in the field of digital infrastructure management. Each party, platform, advertiser and regulator, claims to be concerned with improving the ‘experience’ for users, yet the above examples show that there are several standards currently being deployed in the management of platform infrastructure.

There’s a case to be made that the platform’s efforts to combat what they see as overly intrusive or irritating advertising on their properties are an exercise in public relations. Do the seemingly benevolent Silicon Valley and Mountain View pronouncements and decrees around privacy and tracking relate more to a genuine desire to safeguard users, or to protect their own metrics, and consequently commercial interests?

Perhaps the real answer lies somewhere in between.

References

“Unified autoplay.” blog.chromium.org, 2017. Google. Accessed 18 Sept. 2017. <https://blog.chromium.org/2017/09/unified-autoplay.html.>

Dalrymple, Jim. “Apple responds to ad group’s criticism of Safari cookie blocking”. The Loop, 2017. Accessed 18 Sept. 2017. <www.loopinsight.com/2017/09/15/apple-responds-to-ad-groups-criticism-of-safari-cookie-blocking/.>

Egelman S., Felt A.P., Wagner D. ‘Choice Architecture and Smartphone Privacy: There’s a Price for That.’ The Economics of Information Security and Privacy, edited by Böhme R. Springer, 2013. pp. 211-236.

“eMarketer Scales Back Estimates of Ad Blocking in the US.” eMarketer.com. 2017. Accessed 19 Sept. 2017. <www.emarketer.com/Article/eMarketer-Scales-Back-Estimates-of-Ad-Blocking-US/1015243.>

Greene, Diane. “As G Suite gains traction in the enterprise, G Suite’s Gmail and consumer Gmail to more closely align”. Blog.google. 2017. Google. Accessed 19 Sept. 2017. <www.blog.google/products/gmail/g-suite-gains-traction-in-the-enterprise-g-suites-gmail-and-consumer-gmail-to-more-closely-align/.>

Gomer, Richard; Mendes Rodrigues, Eduarda; Milic-Frayling, Natasa; Schraefel, M. C. “Network Analysis of Third Party Tracking: User Exposure to Tracking Cookies through Search.” IEEE/WIC/ACM International Joint Conferences on Web Intelligence, Nov. 2013, Vol.1, pp.549-556

Hern, Alex. “Apple blocking ads that follow users around web is ‘sabotage’, says industry.” The Guardian. 2017.Accessed 19 Sept. 2017. <www.theguardian.com/technology/2017/sep/18/apple-stopping-ads-follow-you-around-internet-sabotage-advertising-industry-ios-11-and-macos-high-sierra-safari-internet.>

Kitchin, R. “Big Data.” The Data Revolution. London: Sage, 2014. 67 – 80. Print.

Lee, Newton. “Social Networks in the Age of Privacy.” Facebook Nation, 2nd Ed. New York: Springer, 2014. 23 – 55. Print.

Ramaswamy, Sridhar. “Building a better web for everyone”. Blog.google. 2017. Google. Accessed 20 Sept. 2017. <www.blog.google/topics/journalism-news/building-better-web-everyone/.>

Swant, Marty. “Every Major Advertising Group Is Blasting Apple for Blocking Cookies in the Safari Browser.” AdWeek. 2017. Accessed 18 Sept. 2017. <www.adweek.com/digital/every-major-advertising-group-is-blasting-apple-for-blocking-cookies-in-the-safari-browser/.>

Thomas, Dallas. “23 Important iOS 10 Privacy Settings Everyone Should Double-Check”. Gadget Hacks. 2017. Accessed 21 Sept. 2017. <ios.gadgethacks.com/how-to/23-important-ios-10-privacy-settings-everyone-should-double-check-0173873/.>