ArtPassport: How Virtual Reality Technology is Shaping Our Cultural Experiences

Pesce, Maurizio. “Google Cardboard 2.” Wikimedia Commons, 29 May 2015, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Google_Cardboard_2_(18446561558).jpg. Accessed 18 Sept. 2017.

One of the most influential figures of our time, Apple co-founder Steve Jobs once said, “Innovation distinguishes between a leader and a follower.” On the contrary, writer Evgeny Morozov believes that “Celebrating innovation for its own sake is in bad taste” (21). These quotes seem to essentially summarize the social climate we live in today. These polarizing views shape how most people view technological innovation; while some praise innovation and its gradual dissemination of accessibility and convenience, others find it to be heading towards a kind of dystopic world devoid of meaningful human connection. As the world becomes increasingly digitalized, virtual reality (VR) has become an object of curiosity for technocrats and ordinary people alike. Although VR finds its origins as early as the 1990’s, it has been gaining prominence in recent years and has become far more accessible to the general public. A simple Google search for “google cardboard virtual reality headset” results in a selection of various online shops that sell them at a starting price of only 3,95 euros.

The Popularity of VR

The charm of this phenomenon is outlined by Michael Heim in his work The Metaphysics of Virtual Reality. He finds that VR does not simply entertain or allow temporary escape, but it in essence transforms reality as such that we build a new sense of perception and awareness of our surroundings (Heim 124). He even touches upon how VR can potentially alter our understanding of presence, instead of just spectating or viewing and having vision be the primary sense, VR could eventually engage the other four senses simultaneously and enhance our perceptions (128). So, VR is far more than a plaything. Its constant development, improvement, and popularity can in fact have serious implications on how we might immerse with the future world.

The gaming world has undoubtedly been one of the biggest adopters of VR. This seems understandable as the natural aim of gaming is to wholly sensorially immerse the user, and what better way to achieve this than through a headset that can virtually elevate the gamer into another realm? However, VR is slowly making its way into educational and other cultural institutes. Museums have become curious about the ways in which VR can enhance the museum-goer’s experience and indulge them further in the artworks on display. The Cultural Center “Hellenic Cosmos” in Athens held a VR Cave wherein a digital reconstruction of the old town of Miletus could be experienced. Albeit impressive in its details, the essence of the town was missing, “after all, the buildings were made by and for their inhabitants. What is a town without people” (Mosaker 18)? Therefore, even though the visuals could be appreciated, the model was partly unsuccessful in creating an understanding of the cultural past of Miletus. Similarly, not technically virtual reality but still digital, the app Kunstporten was designed by Norwegian experts to complement the artworks in seven different museums. The app created more interest in the art especially among the youth, but still visitors seemed more fascinated by the app than the art, and the creators’ “working ‘head up’ instead of ‘head down’” policy seemed to falter (Varvin et al. 281).

In a recent article by The Verge, Nikki Erlick explores how the integration of virtual reality is affecting different museums. She finds that the trigger for the adaptation of digital means in historical and non-historical museums, is due to the decline of visitors over the past two decades, in particular millennials. To create enthusiasm among the younger generations for the displayed art, virtual means have been taken up by museums. One of the most startling statistics that prove the efficiency of VR is one provided by the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum who found that the implementation of digital interaction and immersion methods led to the average visitor age to drop from from 60 years old in 2011 to 27 years old in 2014 (Erlick). It is especially interesting that museums representing history are willing to accommodate the virtual and digital, even though the two respectively symbolize the old and the new, and there may be a lingering fear of the latter hindering the experience of the former. Even if any such interference is occurring, at the least more people of different age groups are drawn to museums, which is already an improvement from not attending at all.

Stenger, Nicole. “Stenger with VPL gear.” Wikimedia Commons, 4 July 2013, upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/61/Nicole_Stenger_Virtual_Reality.jpg/996px-Nicole_Stenger_Virtual_Reality.jpg. Accessed 18 Sept. 2017.

ArtPassport

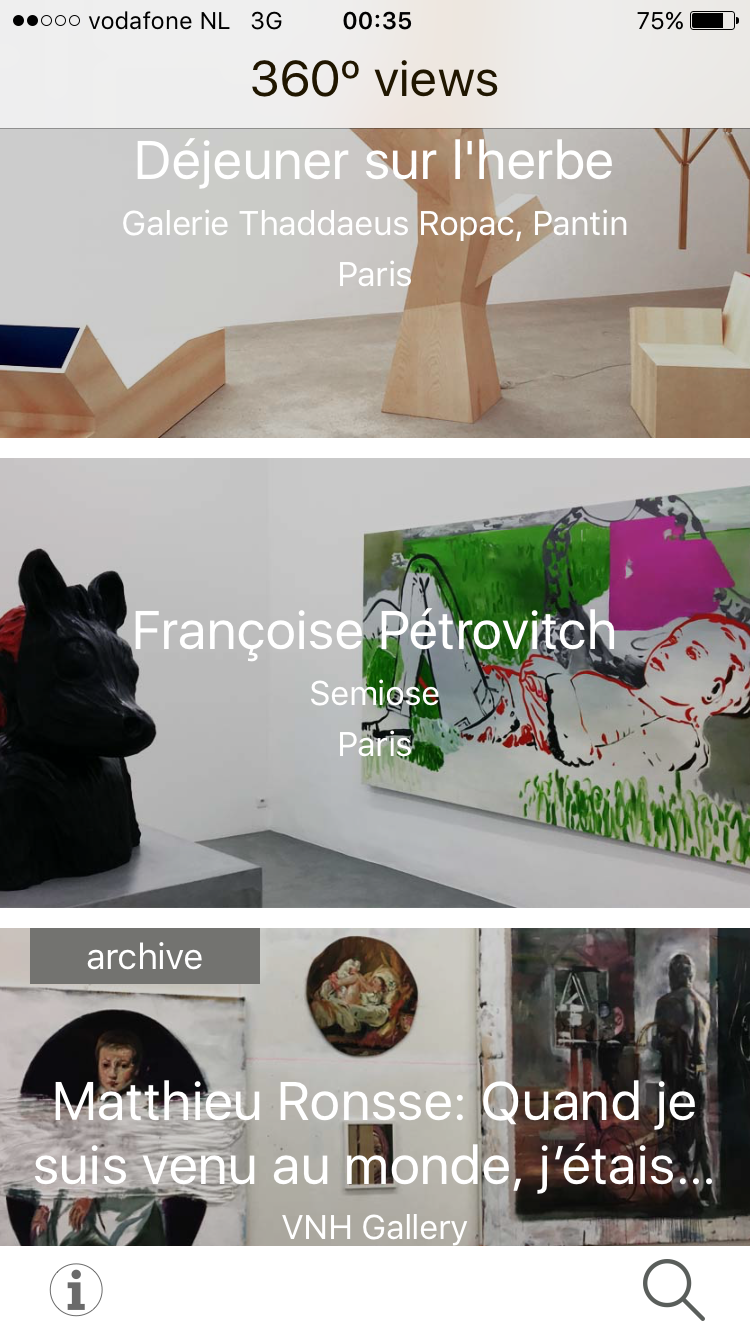

In May of 2017, the London-based organization GalleriesNow released a free-to-download app on iTunes called ArtPassport. The aim of the app is very simple: to provide the user with 360 degrees panoramas of art exhibitions from all over the world, with a focus on modern and contemporary art. The director of GalleriesNow, Tristram Fetherstonhaugh’s, intention is to engage not only art connoisseurs but anybody who is interested in art at all (CultureLabel). The archiving quality of the app erases the problem of ephemerality as galleries are usually temporary. Now with ArtPassport you can access any gallery even if the exhibition has ceased to exist. Accessibility is also a strong point of this application. Clearly it would be ludicrous, if not impossible, to visit every exhibition in various museums around the world in a span of a week or even a month. Best summarized by a technology writer at Forbes, “I can [ . . . ] see things that perhaps I missed when I went to the space, or perhaps that I can’t visit because of time or geography” (Morris).

As if the obliteration of obstacles of distance, expense, and time was not enough, the app also supports VR devices. ArtPassport has a VR icon which at a click gives clear instructions about connecting your headset to the app. Upon downloading the app myself, which is currently only available for iOS users, I became familiar with its workings. The interface is very simple, with the homepage providing an overview of recently added galleries and a search function at the bottom-right corner. Upon clicking on a gallery, you are provided with information about the artworks, artists, and dates and times. The “Visit” button gives you the physical location of the gallery, the “Artworks” button shows you high quality pictures of some works, and the “360” button takes you on a virtual tour of the exhibition. Thus far according to the U.S. iTunes website, from a total of 23 ratings, the app has received an underwhelming average of two and a half stars out of five. I was only able to access one comment which gave a five star rating and expressed much enjoyment and support for the app. Then why is the overall rating so low? There could be several reasons, including glitches in the app, but I want to explore the cultural aspect of why this app may not garner as much support as expected.

ArtPassport homepage as viewed on the iPhone 6. 23 Sept. 2017.

Solutionism – Fixing What is Not Broken

Earlier in this article Morozov was mentioned, who is very vocal in his opposition to what he claims is technological solutionism. His main point, in brief, is that on-going innovation is trying to create a solution for every problem; even if the problem does not exist, should not be fixed, or is far more complex and not susceptible to a technological fix. He provides the example of cameras that monitor cooking and take note of every mistake you make while preparing your food, in an attempt to improve your skills in the kitchen. He finds such technology bizarre because it takes away the enjoyable aspect of cooking which is making mistakes and progressively improving. He thinks a cookbook does the job and anything beyond it is unnecessary. More importantly such solutionism is harmful, because it gives a reductionist account of human behavior and views every struggle as open to be solved by a device or app (Morozov 21).

Although ArtPassport puts forward an impressive concept, has a charming interface, and a passionate group of art experts behind it, it is hard to substitute the museum-going experience for a virtual one. Being unable to visit certain exhibitions does not strike me as an imperative issue that needs resolving. The museum-going experience is something special, especially for ordinary people who have no professional or personal attachments to art. We have culturally constructed it as something to do to connect with history or art, something to share with others or as quality personal time, something that is confined to physical space and requires a physical visit to be experienced. Allowing this experience to occur on an iOS device through VR may give us the opportunity to look at the artworks, but would not engage our other senses. Heim’s hope for VR engaging us wholly is promising, but taking the human being out of the museum surroundings physically is unconscionable. Upon conversation with fellow students, we nearly unanimously agreed that visiting a gallery or museum also entails smelling the surroundings, this could be paint, photo paper, or even the smell of wires or machines, the spatial awareness, the feeling of the floors or brushing past other people, the sounds of footsteps and visitors discussing the artworks. Just as the VR Cave in Athens and Kunstporten in Norway intrigued the visitors, but did not wholly immerse them, I am afraid the excitement surrounding ArtPassport is more about its 360 and VR capabilities, than the artworks it hopes to represent.

Growing up in the twenty-first century, I am thrilled by technological advents and the prospect of VR creating all-sensory experiences in the near future. However, Morozov has merit in his worries about solutionist approaches and his doubts are mirrored through the creations of apps such as ArtPassport, that greatly simplify cultural and human experiences. Education, simplicity, and accessibility through technology can be fruitful, but not at the cost of compromising human connection and cultural practices.

Calvo, Adrianna. “People at an exhibition.” Pexels, static.pexels.com/photos/21264/pexels-photo.jpg. Accessed 18 Sept. 2017.

Works Cited

“ArtPassport from GalleriesNow: An Interview with Director Tristam Fetherstonhaugh | CultureLabel London.” CultureLabel, www.culturelabel.com/blogs/culturelabel-du-jour/artpassport-from-galleriesnow-an-interview-with-director-tristam-feth. Accessed 18 Sept. 2017.

Erlick, Nikki. “How museums are turning to virtual reality and apps to engage visitors.” The Verge, The Verge, 6 May 2017, www.theverge.com/2017/5/6/15563922/museums-vr-ar-apps-digital-technology. Accessed 18 Sept. 2017.

Heim, Michael. The metaphysics of virtual reality. New York, Oxford University Press, 1994. (chapter “The Essence of VR”)

Limited, GalleriesNow. “ArtPassport on the App Store.” App Store, 12 Sept. 2017, itunes.apple.com/us/app/artpassport/id1220878305?mt=8. Accessed 18 Sept. 2017.

Morozov, Evgeny. 2013. To Save Everything, Click Here: The Folly of Technological Solutionism. New York: Public Affairs. (chapter “Solutionism and Its Discontents”)

Morris, Ian. “Experience Art In VR, From Your iPhone, With ArtPassport.” Forbes, Forbes Magazine, 14 Sept. 2017, www.forbes.com/sites/ianmorris/2017/09/14/experience-art-in-vr-from-your-iphone-with-artpassport/#6270df15372e. Accessed 18 Sept. 2017.

Mosaker, Lidunn. “Visualising historical knowledge using virtual reality technology.” Digital Creativity, vol. 12, no. 1, Jan. 2001, pp. 15–25., doi:10.1076/digc.12.1.15.10865.

Varvin, Gunhild, et al. “The journey as concept for digital museum design.” Digital Creativity, vol. 25, no. 3, May 2014, pp. 275–282., doi:10.1080/14626268.2014.904365.