Digital Gerrymandering, Computational Propaganda and the Electronic Electoral Advantage: Towards a Case for Reform

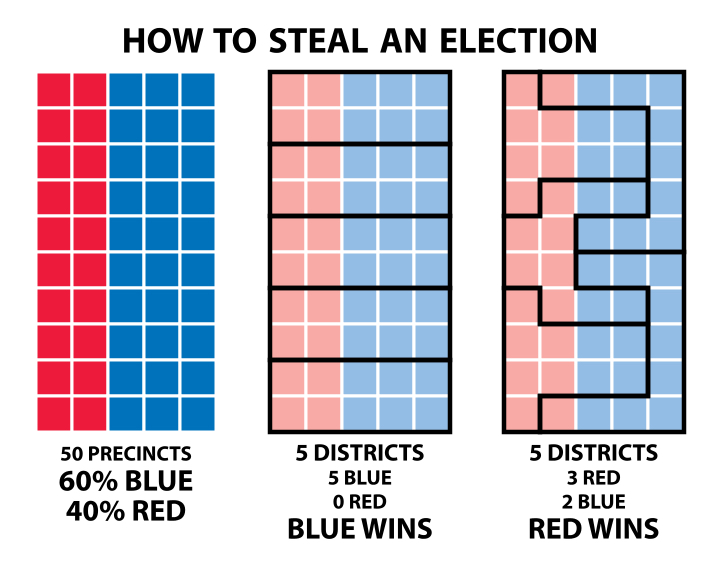

Jonathan Zittrain, professor of international law at Harvard University, coined the term ‘digital gerrymandering’ in 2014. Traditionally, gerrymandering was the political practice of manipulating constituency boundaries to cultivate a party-political advantage. Although the etymology derives from Elbridge Gerry’s governorship of Massachusetts in 1812, constituency deficiencies have persisted far longer.

The ideology of gerrymandering derives, in part, from the British phenomenon of ‘rotten boroughs’. Because of a failure to update constituencies based on contemporary demographic trends, oligarchic elites were able to ‘purchase’ (read: bribe) parliamentary boroughs, often containing just a dozen houses, to elect their favoured representative to the House of Commons.

So what is digital gerrymandering?

Zittrain defines it as “the selective presentation of information by an intermediary to meet its agenda rather than to serve its users” (336). Yet the interpretation seems vague and in need of elaboration.

Four years previously, in 2010, Facebook and the University of California, San Diego, combined to conduct a sociological experiment published in Nature. The study, involving over 61 million unwitting participants, sought to measure the social influence of political mobilisation via ‘nudging’ a certain user set to vote in the upcoming congressional elections (Bond et al).

With this in mind, Zittrain considers a hypothetical: Suppose a partisan Mark Zuckerberg “creates a very special group that won’t receive the message. He knows that Facebook ‘likes’ and other behaviours can easily predict political views … Zuck simply chooses not to spice the feeds of those unsympathetic to his views with a voter encouragement message” (336).

Although it is a very specific hypothesis, yet Zittrain has tapped into the crux of a much broader issue within new media: The potential manipulation of technology to advance partisan beliefs. This can take two forms.

Digital gerrymandering by tech:

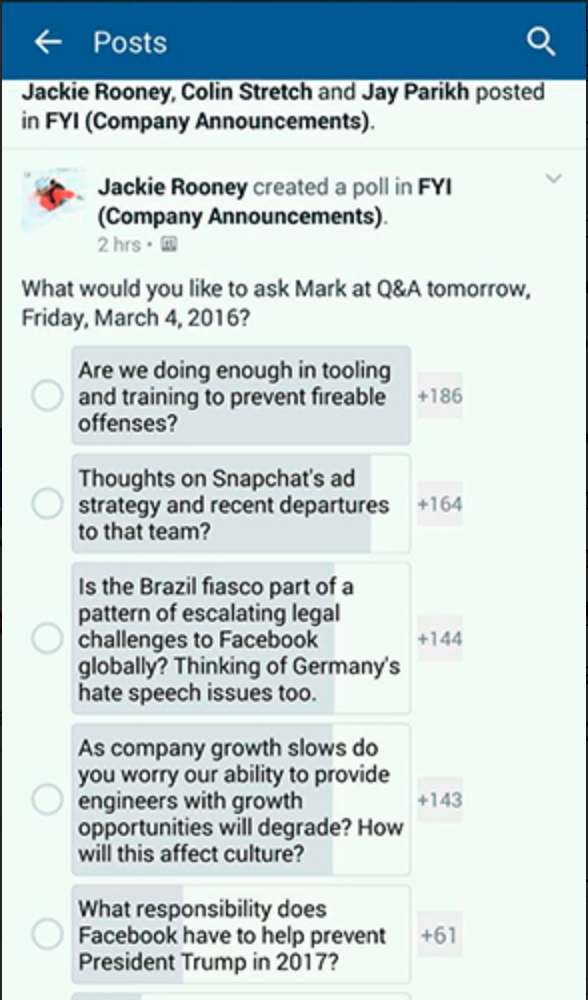

The first is envisaged by Zittrain: Digital gerrymandering by ‘big-tech’ juggernauts. Although Silicon Valley have constructed a discursive framework positioning themselves as neutral gatekeepers of an objective reality, there is evidence to suggest that at least some of the biggest players harbour political bias (Nunez; 2012 Presidential Race Fundraising).

A screenshot from an internal Facebook employee poll. Source: Gizmodo.

As both monopolies on knowledge and aggregates of vast datasets of vote-eligible citizens, these private institutions are in a unique position to exploit these advantages to befit a political agenda if they wish.These exploitations are deeply rooted in the fields of behavioural economics and psychometrics. Already big data companies are springing up, augmenting consumer datasets and cross-referencing them with the OCEAN (openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism) personality model in order to pinpoint everything from our class, diet, education level, music taste – and political leanings (Grassegger & Krogerus).

Robert Epstein has perhaps worked most extensively on the political implications of big tech companies utilising psychological techniques. Discovering what he calls the ‘search engine manipulation effect’ (SEME), he describes the way in which our consumer or political preferences can be unconsciously altered by exploiting inherent cognitive weaknesses, such as the negativity and confirmation biases (Fallis 154-55), and the serial position effect (Troyer 2263-64).

In one study into SEME published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Epstein and Robertson found that deliberately biased search results could increase the likelihood of an undecided constituent voting for the preferred candidate by 48% (Epstein & Robertson E4513).

It’s important to note, however, that SEME does not exist in a psychological vacuum enacted by a ‘Homo Psychologicus’. While the serial position effect, along with other biases, are hugely influential, these effects are played out in the context of deeply internalised socio-cultural norms. Our instinctive trust of Google, for instance, and our distrust of the ‘partisan’ mainstream media. Epstein does mention these contributory factors in later discussions (Google Can Shift Votes 25).

This debate around big data, politics and behavioural economics ultimately leads back to ‘nudges’. The nefarious motives articulated by Zittrain and Epstein are a far cry from Thaler & Sunstein’s ‘libertarian paternalism’ (Nudge 4-14). Rather, digital gerrymandering seems to fall within Karen Yeung’s moniker ‘hypernudge’, which schematises nudges as “brought about by the algorithmic configuration of informational choice architecture seeking to ‘nudge’ her click-through behaviour in directions favoured by the choice architect” (Yeung 121; emphasis added).

So far, we have explored the potential for tech companies to exploit their platforms to further a perceived political agenda, along with a brief psychological contextualisation. But is another type of digital gerrymandering?

Digital gerrymandering by parties:

“The Tories Are Exploiting A New Spending Loophole To Launch A Last-Minute Facebook Ad Blitz” was the headline Buzzfeed ran with on June 7, one day before the United Kingdom’s 2017 general election (Waterson & Dugan). Under UK electoral law, there are two limits on advertising spend by a party: Up to £19.5m for the central government, but just £10-16,000 for individual, local candidates. Because of these disproportionate spending limits, there is a huge incentive for candidates to pass off local campaigning expenses as national costs. And this problem is further exacerbated by a first-past-the-post electoral system, which places enormous significance in a few marginal constituencies.

The rise of social media advertising in political campaigns has birthed new opportunities to manipulate electoral regulations. The loophole Buzzfeed referred to involved the Conservative Party using Facebook’s geo-targeting feature to overwhelm the UK’s marginal seats with customised advertisements. Electoral regulations currently stipulate that advertisements that promote the party are likely to be paid for from the central government’s advertising budget (Electoral Commission 3:14). By using geo-targeted ads without mentioning the local candidate’s name, this effectively gave the Conservatives an almost unlimited budget to spend on the most crucial swing seats in the country.

This was facilitated by a hopelessly outmoded regulatory system. The Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000, from which the UK derives most of its electoral laws, was passed four years before the creation of Facebook. Since then, Facebook in the UK has grown exponentially. According to the website Statista, it now has 44 million unique users and 74% of the UK’s social networking market share (Leading Countries of Facebook Users; Market Share). The website also dominates digital advertising budgets for political campaigns, which has a causal relationship with the growing trend of eschewing traditional broadcast media advertising in favour of the micro-targeting Facebook offers.

Whilst the digital advertising landscape is left largely unregulated, the UK retains strict regulations on political advertisements in broadcast media. Political advertisements on television are banned in order to promote a ‘level playing field’, and a report from LSE’s Media Policy Project notes that UK broadcasting licences contain a caveat of political impartiality (Goodman et al. 7). The report also notes that “political advertising on non-broadcast media are exempt from the Advertising Code, and therefore not subject to regulation by the Advertising Standards Authority, leaving it essentially unregulated” (8).

These two examples of digital gerrymandering don’t effectively clarify what, if anything, digital gerrymandering is. In its broadest context, digital gerrymandering stands at the intersection of big data, behavioural economics, psychometrics, micro-targeting and, crucially, political partisanship. Yet given the differential nature of the two practices explored above, the term seems insufficient. There are still many strands left unexplored by this post. The role of automated ’bots’, for instance, in shaping online political discourse around the EU referendum.

Perhaps the Oxford Internet Institute, an organisation leading the discussion around these bots, give us a more useful term for conceptualising digital gerrymandering, even if used narrowly themselves: computational propaganda.

Tools:

This collision of technology and electoral politics has spawned an array of fascinating tools and platforms which warrant analysis in their own right. Berghel, for instance, has touched on the potential geopolitical ramifications of cross-referencing Geographic Information Systems (GIS) with huge datasets to remap constituencies along partisan lines. Tools such as iRedistrict and Redistricter, in the hands of nefarious political agents, could easily be used to circumvent the democratic process (Chasing Elbridge’s Ghost, 2016).

A GIS developed by the University of Southern Carolina. Source.

In recent years, partisan ecosystems have also been developed by third parties, aiming to sell software to causes looking to cultivate ‘walled garden’ communities and lock users inside echo chambers. Nation Builder is perhaps the most popular, which offers a ‘turn-key’ solution to online community engagement, with integration for WordPress, Paypal and Mailchimp. A report claims the ‘Remain’ campaign of the EU referendum used analytics software supplied by Nation Builder. The software encourages canvassers to assign each voter a score based on their likeliness to vote remain. This data was then processed and used to produce target lists for Facebook advertising and telephone canvassing (Mullen 89).

A screen taken from Nation Builder’s website. Source.

Another company, used by both the Donald Trump campaign and the ‘Leave’ camp of the EU referendum, offers bespoke app creation based on principles of gamification and psychometric targeting. A report by Business Insider claims that uCampaign matches the contact files of a user’s address book with profiles harvested by ‘conservative big data groups like Cambridge Analytica’ to identify which users to send a text message to, encouraging them to vote (Tani 13).

Some of uCampaign’s customers. Source.

Electoral manipulation is a practice almost as old as democracy itself. So what is unique about computational propaganda? It is useful here to take five of Fogg’s ‘captology’ (computers as persuasive technology) schema (Fogg 5-11):

- Anonymity: Computational propaganda can now occur either within, or by, media ecosystems owned by private institutions. In the case of Google, the reliance on algorithms to ‘objectively’ present data makes it extremely difficult to spot purposeful bias. The fact that these algorithms are proprietary and largely beyond the scope of investigatory powers raises questions of accountability.

- Manage huge volumes of data: This problem is amplified by big data and its application to micro and geo-targeting. Thousands of unique political adverts can be tailored to specific demographics. In the case of first-past-the-post systems, psychographic analysis of millions of voters can be leveraged to determine swing voters who usually decide elections.

- Use many modalities of influence: Parties are able to communicate to voters with a dizzying panoply of multimedia. Graphics, text, videos, hyperlinked content and gamification can all be utilised within custom-built ‘walled garden’ applications supplied by third parties.

- Scale easily: The director of the Vote Leave EU campaign said: “we ran many different versions of ads, tested them, dropped the less effective and reinforced the most effective in a constant iterative process” (Cummings 13).

- Ubiquity: Imagine it’s 11pm. You receive an automated SMS from a friend who has downloaded the Donald Trump app. The message encourages you to vote for him. Now imagine a canvasser, who you have never met, knocking on your door at around this time.

To be clear, there is no evidence to suggest that the big-tech companies have engaged in computational propaganda. What’s more, at present, political parties have only flirted with it. However, the coming together of new media and electoral politics has, in reality, only just begun. Returning to Zittrain: ‘the mechanisms are in place’ (338).

References:

‘2012 Presidential Race | OpenSecrets’. N.p., n.d. Web. 25 Sept. 2017.

Berghel, Hal. ‘Chasing Elbridge’s Ghost: The Digital Gerrymander’. Computer 49.11 (2016): 91–95. CrossRef. Web.

Bond, R. et al. ‘A 61-Million-Person Experiment in Social Influence and Political Mobilization’. Nature 489.7415 (2012): 295–298. Web. 24 Sept. 2017.

Cummings, Dominic. ‘On the Referendum #20: The Campaign, Physics and Data Science – Vote Leave’s “Voter Intention Collection System” (VICS) Now Available for All’. Dominic Cummings’s Blog. N.p., 29 Oct. 2016. Web. 25 Sept. 2017.

Dugan, Emily, and Jim Waterson. ‘The Tories Are Exploiting A New Spending Loophole To Launch A Last-Minute Facebook Ad Blitz’. BuzzFeed. N.p., n.d. Web. 24 Sept. 2017.

Electoral Commission, ‘UK Parliamentary general elec on 2015: guidance for candidates and agents’, 3:14.

Epstein, Robert. ‘“Google Has Power to Control Elections, Can Shift Millions of Votes to Clinton”’. RT International. N.p., n.d. Web. 25 Sept. 2017.

Epstein, Robert, and Ronald E. Robertson. ‘The Search Engine Manipulation Effect (SEME) and Its Possible Impact on the Outcomes of Elections’. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112.33 (2015): E4512–E4521. Web.

‘Facebook Users by Country | Statistic’. Statista. N.p., n.d. Web. 24 Sept. 2017.

Fallis, T. The Oxford Handbook of Political Communication. Ed. K Kenski and K Jamieson. Oxford University Press, 2017. Print.

Fogg, B. J. ‘Persuasive Technology: Using Computers to Change What We Think and Do’. Ubiquity 2002.December (2002): n. pag. ACM Digital Library. Web. 25 Sept. 2017.

Goodman, Emma et al. (2017) The new political campaigning. LSE Media Policy Project Series, Tambini, Damian and Goodman, Emma (eds.) Media Policy Brief 19. The London School of Economics and Political Science, London, UK.

Grassegger, H, and Krogerus, M. ‘The Data That Turned the World Upside Down’. Motherboard. N.p., n.d. Web. 24 Sept. 2017.

Mullen, Andrew. ‘Leave versus Remain: The Digital Battle’. EU Referendum Analysis 2016: Media, Voters and the Campaign. Ed. Jackson, Daniel and Einar Thorsen and Dominic Wring. Bournenmouth: The Centre for the Study of Journalism, Culture and Community. 2016.

Nunez, M. ‘Facebook Employees Asked Mark Zuckerberg If They Should Try to Stop a Donald Trump Presidency’. Gizmodo. N.p., n.d. Web. 24 Sept. 2017.

‘Social Networks Ranked by Market Share UK 2017 | Statistic’. Statista. N.p., n.d. Web. 24 Sept. 2017.

Tani, Maxwell. ‘Donald Trump’s Campaign Is Using the Same App the “Leave” Campaign Used during Brexit to Spur Voter Turnout’. Business Insider. N.p., 7 Nov. 2016. Web. 25 Sept. 2017.

Thaler, Richard H, and Cass R. Sunstein. Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness. , 2009. Print.

Troyer, Angela K. ‘Serial Position Effect’. Encyclopedia of Clinical Neuropsychology. Ed. Jeffrey S. Kreutzer, John DeLuca, and Bruce Caplan. New York, NY: Springer New York, 2011. 2263–2264. Web.

Yeung, Karen. ‘“Hypernudge”: Big Data as a Mode of Regulation by Design’. Information, Communication & Society 20.1 (2017): 118–136. Web.

Zittrain, J. (2014). Engineering an Election: Digital gerrymandering poses a threat to democracy. Harvard Law Review, 127(8), p.336.