Instagram bots in the debate of free labor

In the recent years there has been a growing trend of Instagram bots creating accounts, liking content and posting comments on Instagram. For a cheap price, these bots are offered as a service, by sites such as Gramista to users who want to inflate their engagement with other users. These Instagram bots serve, specifically, as an effective marketing mechanism, mimicking human behavior, in order to attract the attention of users in the hopes that the users will follow or like them in return.

In an article, conducted by Digiday.com, an Instagram influencer has admitted the usage of Instagram bots, in order to artificially inflate the engagement with users. The influencer states that there was a necessity to grow followers, as brands pay influencers for their reach and their capability to make the products well known on certain platforms. Brands are willing to pay users to advertise products, as users are tended to click more on an ad if a friend likes that particular ad. In other words, this influencer reflects on the notion that user activities on Instagram can be seen as part of labor, as building a substantial followers base is fundamental to attract brands, which are willing to pay users to promote a product.

In this article I point out that Instagram bots, offered by web services such as Graminsta, allow us to critically reassess if user activities can be seen as a form of free labor that is being exploited by platforms such as Instagram. In the debate of free labor Terranova argues that web services are reliant on the activities of users, without financially compromising them for their activities. Simultaneously, Terranova argues that free labor is not necessarily exploited, as users voluntary generate activities and they seem to enjoy it. (Terranova 2012, 34). I argue that Instagram bots implicate the concept of free labor and exploitation, as it reveals the marketing and capitalistic objectives of (some) users on Instagram. Within this line of thought I argue that there is an asymmetrical relationship, between users and Instagram, as both strive for profit, but Instagram is extracting most economic value. Although one could argue that Gramista artificially generates the activities of users and thus they do not actually do the work, I argue that this argument is too black and white, as the Instagram bots work in such an unnoticeable way (due to the manner in which they mimic human behavior and the possibility for users to manually produce and consume content while the Instagram bots are active) that it blurs the lines between human production/consumption and technological production. Lastly, by considering Instagram bots as part of the production process of activities and content on platforms, I implicate concepts such as prosumer (Ritzer & Jurgenson 2008) and produser (Bruns 2008), which describes the blurring line between production and consumption on platforms that are typically referred to as human activities.

How do the Instagram bots on Graminsta work?

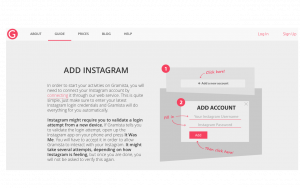

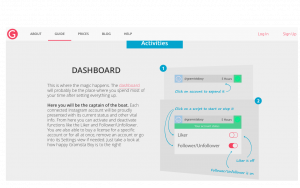

Graminsta is a service that puts science in marketing, by copying human behavior. To start the activities users need to connect their Instagram accounts, with the web service of Graminsta (image 1). In the dashboard users are presented with the current status and other vital information concerning their Instagram account. In the dashboard users can activate and deactivate functions like the Liker and Follower/Unfollower (image 2). The function Liker automatically likes other users content and is based on the notion that other people will like in return. You can adjust the speed level of this function. So it is possible that the Liker will like content on a slow level, but also on speed level. The smart mode will automatically follow and unfollow users. The basic idea is that when you follow people, they will follow you back. After a while when the smart mode has recognized that you’ve followed a maximum of followers it will start to unfollow those users, without them even knowing. The aim is to keep the amount of users that you follow low, while your followers base keeps on growing. In the setting users can target people according to hash tags, locations, blacklists and time zone.

Image 1: Add instagram account to Gramista

Image 2 Dashboard Gramista

Produser, Prosumer, Free labor and exploitation on Instagram

Fundamental to the debate of free labor is the intersection of production and consumption of content on Web 2.0 platforms such as Instagram. This intersection of production and consumption has led to portmanteaus such as:

- Produser; which blurs the boundaries between the passive roles of users as media consumers and the active role of users as producers of media content. (Bruns 2008)

- Prosumer; which elaborates on the intersection between production and consumption and adds that there is a trend towards users doing unpaid work, by offering products at no cost. It simultaneously raises questions concerning whether users are being exploited for their unpaid labor, as the owners of Web 2.0 enterprises extract value from this labor (Ritzer & Jurgenson 2008).

While these concepts are very useful to elaborate on in the discussion of how users are active producers and passive consumers of media content, these concepts seem to neglect the productivity of actors such as bots. One could argue that with regard to Instagram bots, that when we speak of the production of activities on Instagram, there is an intertwinement of active human and technological actors. I point out that this is due to that Instagram bots work in such an unobtrusive manner that it is possible, for users to manually produce and consume content, while the Instagram bots are active. This makes it difficult for other users to distinguish human activities from the activities of bots on the platform.

The blurring lines between human activities and the activities of Instagram bots is interesting, because it allows us to consider Instagram bots as an actor in the discussion of free labor, as they contribute to the production of media content. A scholar who elaborates on the notion of free labor and exploitation is Terranova, who points out that users can be seen as a source of monetary value in the digital economy, as web services are reliant on the participation and active contribution of users (2000). However, she point out that free labor is not necessarily exploited, as free labor is voluntarily given and users seem to enjoy the activities they undertake (Terranova 2012, 34). I argue that to some users the motives to (artificially) produce content is not simply, because they enjoy it, but that they see their activities as a way to market themselves in order to extract economic value. I argue that the Instagram bots play a significant role in this marketing process, as they stimulate the circulation of the content, and inflate the reach and influence of users on Instagram. One could point out that users are exploited for their labor on Instagram, as this platform draws on the audience participation to valorize the advertising space they sell to advertiser, but do not pay their audiences for it. As both parties (users and Instagram) try to maximize profit, users suffer infinite level of exploitation as the revenue of Instagram is forecasted to be at 5.5 billion and users are not compromised for their activities (Arvidsson & Colleoni 2012, 136). This creates an asymmetrical relationship between users and Instagram. In this sense, one could argue that users are exploited in the same sense as underpaid workers, because the notion that users voluntarily produce content and enjoy the activities on the platform does not always apply, as there are users whose motives are driven by marketing and capitalistic purposes.

Conclusion/Discussion

In this article I have discussed how Instagram bots implicate the notion of production and consumption on Instagram, by shedding light on the intertwinement of human and bot activities. I’ve argued how the use of Instagram bots reveals the marketing and capitalistic purposes of users and how their activities can be seen as a form of free labor that is exploited by Instagram, creating an asymmetrical relationship between users and Instagram. Although these insights are interesting, there are some shortcomings such as that Arvidsson & Colleoni argue that labor on online prosumer platforms are hardly related to time and that is what is being valorized is not the amount of likes or comments, but the ability to mobilize affective attention and engagement (2012, 135, 144). Due to the short length of this article I suggest that in further research one could take up this shortcoming by arguing that for users the time spent building ones account (artificially or not), is the time they need to invest to produce the equivalent of their own livelihood. Another shortcoming of these insights is that not all users have marketing and capitalistic motives and thus the notion of Instagram bots are not applicable for every user. To conclude, I want to suggest a solution for the asymmetrical relationship, where Instagram incorporates a function into their interface, where users can choose to promote a brand and get paid according to how many other users they have reached and influenced.

References

Arvidsson, Adam, and Elanor Colleoni. 2012. “Value in Informational Capitalism and on the Internet.” The Information Society 28 (3): 135–50. doi:10.1080/01972243.2012.669449.

Bruns, Axel. 2008. Blogs, Wikipedia, Second Life, and Beyond: From Production to Produsage. New York:

Peter Lang. Ritzer, G. and Jurgenson, N. (2008) ‘Producer, Consumer . . . Prosumer?’, paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Sociological Association, August, Boston, MA.

Terranova, Tiziana. 2000. “Free Labor: Producing Culture for the Digital Economy.” Social Text 18 (2): 33–58.

Terranova, Tiziana. 2012. “Free Labor.” In Digital Labor: The Internet as Playground and Factory, edited by Trebor Scholz, 33–57. New York, NY: Routledge