Privatising public transport: tech companies are getting their foot in the door of London’s public transport

Route-planning app Citymapper has decided to take public transport into its own hands. It seems the popular urban navigation app, after years of watching the bus routes of London, didn’t like what it saw, and now a Citymapper-branded bus has launched.

Source: Citymapper

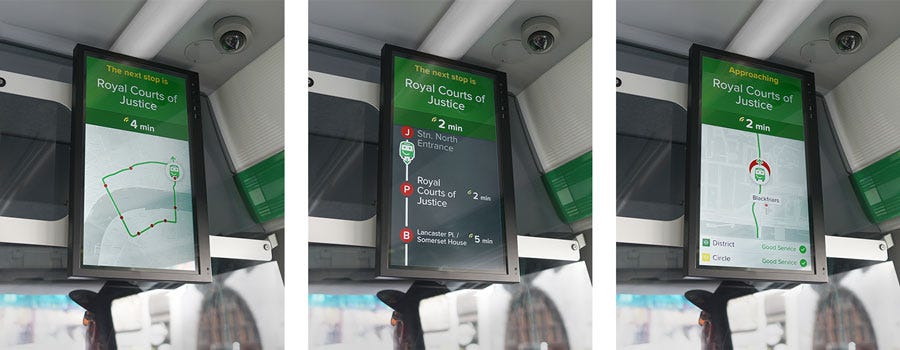

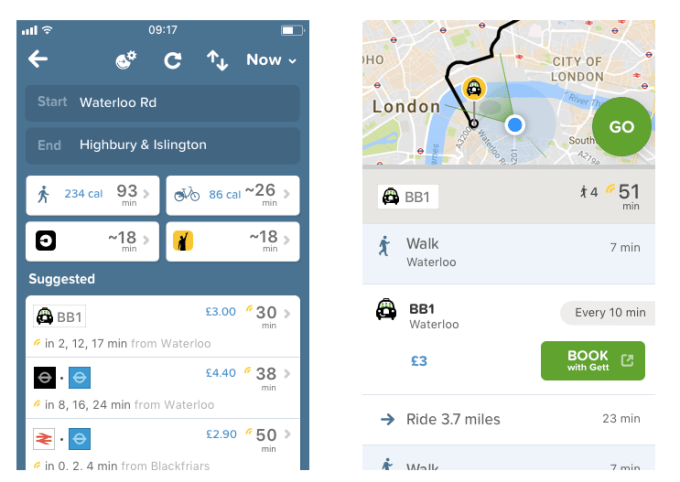

They began their venture with short trial and have recently begun a night bus route called the CM2 running in East London between Aldgate East and Highbury and Islington. Their buses are green (in colour, not in eco-friendliness) with ‘smart’ displays, USB ports and real-time app updates about bus locations and number of spare seats. Recently Citymapper also announced a partnership with London black cab hailing app Gett, and their plans for a ‘black bus’ – essentially a black cab turned into a bus by running along a regular fixed route and picking people up along the way.

It is quite rare to see a software company move into the physical world like this, let alone in such a swerve of their business model. One action of piggybacking on the existing infrastructure of Gett cabs, and one of building and running their own new material forces. Not even Uber expanded beyond software – a big part of its rationale was not owning its own cars. But now that Citymapper is in the hardware realm I think there are two questions pertinent: why do it in the first place, and what are the implications of companies like this running our transport?

The conversation about a new company entering its horse into the London transport race is especially interesting because of the very recent news that Transport for London (TfL) will not be renewing Uber’s license. Uber had aimed to get a monopoly on taxi service, running up against the iconic black cabs, but have now been thwarted and kicked out of the runnings. Could the Citymapper bus be the new rival of iconic London transport? It seems like an odd area to run against; the bus service in the city has constant renovations and improvements, 8000 buses running 700 routes and carrying 1.8 billion passengers in a year. The ‘why’ question seems pretty pressing.

Why?

Modernising the old system

Citymapper have said that they used data from running their app to decide on gaps in the transport infrastructure of the city. They saw that the night routes in East London were lacking so decided to fill them up with their CM2 Night Rider. This is their answer to the ‘why’ question, and more generally they state that existing transport systems are inflexible and old-fashioned in terms of the routes they run. Citymapper aims to keep an eye on customer demand and tailor bus routes to fluctuating needs. This seems a little far fetched for a city bus, but if passengers are finding them via app anyway maybe it isn’t such a wild idea. The only problem is that as it stands, regulations for buses in London only allow fixed routes, so a core idea behind the project of flexible routes is already dead on arrival.

Source: Citymapper

Being ‘smart’

One word Citymapper has stressed repeatedly is ‘smart’. Their buses will be smart, screens will be smart, routes and (presumably) drivers will be smart. This word has less and less meaning as technology moves forward, but it seems as ever that it just means the physical elements of the bus are connected with the interactive software. However, as Morozov (2016) has said, ‘smart’ is merely a synonym for ‘privatised’. Citymapper’s new buses are not any smarter than the public bus system, they are just another private company trying to get a slice of the London bus action.

Source: Citymapper

A crucial indicator of this is that the green buses will not accept Oyster cards, the universalised London transport card. They only accept contactless or mobile payments, whereas red London buses accept these as well as Oyster cards. TfL has given the company permission to run alongside them, and perhaps the connection with Oyster cards will come in the future, but for now it just looks like the first steps of a big company’s aim to take over a well-established market.

What are the implications?

The tech industry is a giant, and one that has not only the resources to displace existing structures, but its success is almost measured by this capacity to disrupt (Preston, 2015). The companies may promise a cheaper or more convenient way, but at the heart of it they are still operating for the purpose of making money. We can see this in Uber, for example: they kept their prices so low that they were turning losses, but investors held their interest because the company planned to hike up their prices once they had crushed their competition. The hierarchical force behind these companies always looks friendly and helpful on the outside, but still aims towards monopolising its industry and deposing less profitable structures that focus on the people.

There is no indication at the moment that Citymapper aims to become as booming an overlord as Uber, however. It just looks a little like the same sort of disruption to an established system as Uber did when it first began threatening black cabs. One difference with the Citymapper bus is that right now they are not promising any particular thing it does better than the current London buses. Not that they are cheaper, or more luxurious – only that there are some screens and charging ports. It makes it looks like a tentative toe in the water of the bus game, while they figure out what exactly the basis is that they want to depose the existing system. But, according to Dudley et al (2017), this is the phenomenon of disruptive innovation, and Citymapper has entered into a game where the measure of success is disruption of the existing system.

Taxi drivers in Santiago, Chile protest Uber. Source: Getty

Citymapper’s other venture seems interesting on some other levels. Their ‘black bus’ raises even more ‘why’ questions than the green one. It seems that the selling point of this is cab luxury for a bus price. Except cabs are not buses, and can only hold up to five people at a time. So this seems to solve nothing for the commuting gaps they identified. The times the cabs will run are at rush hours, supposedly to ease the traffic, but it is a little far-fetched to assume that a few cabs holding five people can make that much of a difference. The only explanation here is that Citymapper is taking advantage of a lucrative partnership opportunity with Gett in an attempt to suss out both the bus and taxi taker markets.

The taxi buses also cost £3, which is a little suspiciously low for an expensive vehicle. Even UberPool was rarely that low. This project operates on the existing infrastructure of black cabs, so doesn’t seem like a disruption. But offering cab rides for that cheaply seems reminiscent of the criticisms of Uber in London. It raises the questions of how the drivers can benefit from this if both Gett and Citymapper stand to be the benefactors of the partnership. Now that Uber is no longer allowed in London, maybe this will be the new big private company holding transport workers hostage.

Source: Citymapper

When talking about Citymapper’s move from mapping to physical transport, I think it’s important to broaden the questions and ask what we (the travellers) stand to lose or gain from having our transport owned by tech companies. Tech-led gentrification is well underway, as corporations can undercut locally-owned businesses with lower prices and more expensive marketing, and drive poorer people out of their livelihoods. (Maharawal, 2017) The source of this behaviour is the ruthless competitive hierarchies we see in tech companies that expand like this, and such ruthlessness leads to harm done not only to the displaced local businesses, but their own employees. We see this for example in the ways that Uber have been shown to mistreat their staff. Transport companies like TfL may be interested in profit, but they still operate the public transport system and so it is important for them to keep the public in mind. Citymapper would have no such obligation, and could offer us fleeting pleasures like £3 taxis in return for economically abused workers.

For the moment none of this is a problem: Citymapper has only just begun their foray into operating London buses, and have nowhere near a monopoly. But as tech companies like this decide to delve into public necessities rather than handy software, it is important to keep an eye out for disruption in their end games and carelessness to workers in their means.

References

Dreher, Julia and Pick, Francesca. ‘Sustaining Hierarchy – Uber isn’t sharing’, Kings Review, May 2015.

Dudley, G., Banister, D. and Schwanen, T. ‘The Rise of Uber and Regulating the Disruptive Innovator’, The Political Quarterly, 88: 492–499. 16 May 2017. doi:10.1111/1467-923X.12373

Etherington, Darrell. ‘Citymapper will offer actual paid bus service in London this year’, Tech Crunch, 20 July 2017. https://techcrunch.com/2017/07/20/citymapper-will-offer-actual-paid-bus-service-in-london-this-year/. Accessed 23 Sep 2017.

Lomas, Natasha. ‘Citymapper ties with Gett to launch shared taxi commuter route in London’, Tech Crunch, 21 Sep 2017. https://techcrunch.com/2017/09/21/citymapper-ties-with-gett-to-launch-shared-taxi-commuter-route-in-london/. Accessed 23 Sep 2017.

Maharawal, Manissa. ‘San Francisco’s tech-led gentrification’, City Unsilenced: Urban Resistance and Public Space in the Age of Shrinking Democracy, Taylor & Francis, 2017.

Morozov, Evgeny. ‘Only a cash-strapped public sector still finds ‘smart’ technology sexy’, The Guardian, 11 Sep 2016. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/sep/10/only-public-sector-finds-smart-technology-sexy. Accessed 23 Sep 2017.

Preston, Rob. ‘Digital disruption: it’s not what you think’, Forbes, 20 April 2015. https://www.forbes.com/sites/oracle/2015/04/20/digital-disruption-its-not-what-you-think/#179934689e06. Accessed 23 Sep 2017.

Temperton, James. ‘Citymapper’s bus, Amazon Echo Show: Podcast 317’, The Wired Podcast, 12 May 2017. Podcast.

Temperton, James. ‘UK porn blocks, Citymapper’s bus: Podcast 327’, The Wired Podcast, 21 July 2017. Podcast.