You cannot log out from the grave: The implications of Facebook suggesting immortality within its death policy.

People are barely aware that all their online profiles, pictures, and status updates will remain available online after they decease. When uploading those memories onto Facebook, we create our “digital self”. But when signing up for Facebook, users are hardly conscious about Facebook’s death policy – or, in other words: of what should happen to that “digital self” after they die. Thus, in most cases, according to the default settings, Facebook will keep your “digital self” alive – including the offer to become immortal in its service.

By Marissa Radermacher, Katrin Puvogel & Drea Rodríguez Cervantes.

1. Methodology

The role of the interpretive policy analyst is to map the ‘architecture’ of debate relative to the policy issue under investigation, by identifying the language and its entailments (understandings, actions, meanings) used by different interpretive communities in their framing of the issue. (Yanow 12)

Interpretive policy analysis will help us to identify the meanings of Facebook’s death policy and how they are processed and communicated to its audience. Therefore, we seek support from literary theory (Yanow 17). The reader-response theory represents the idea of not only authors or, in this case, legislators adding meaning to a text, but also the reader acting as an active interpreter of the text. This results in the difficulty that prior existing problems like implementation difficulties may no longer be simply fixed by removing ambiguous policy language, but that user’s and reader’s interpretations cannot be predetermined and controlled (Yanow 18). This implies that the policy investigated can only be interpreted by someone internal to the subject (e.g. Facebook user with own profile). Therefore, interpretive policy analysts “put their skills to the service of many groups, not just elected officials” (Yanow 19). The representation of various user groups and clients is evident in this method. Moreover, it is possible to formulate new ideas for policy actions from this perch.

Working with this method, there are two steps which an interpretive policy analyst should take:

- “Identify artifacts that are significant carriers of meaning for the interpretive communities relative to a given policy issue” (Yanow 20)

- “Identify community relevant to the policy issue that creates or interpret these artifacts and meanings” (Yanow 20)

- The third step an interpretive policy analyst must take, is to engage with the communities’ “discourses” about the given artifact, in this case, Facebook’s death policy (Yanow 20).

The communities’ discourse with our research object is being displayed in the guidebooks that have been written about deceased people’s digital legacies. An example for this is the opus “Your Digital Afterlife: When Facebook, Flickr and Twitter Are Your Estate, What’s Your Legacy?” (Carroll and Romano 1). People start to think about what traces they leave behind online after they die and therefore engage in an ongoing, only recently starting discussion about how to handle the digital afterlife. The fact that people write guidebooks for ordinary users shows that not enough education and information is given to users who sign up for Facebook and other social media platforms. Therefore, we investigate in how far Facebook suggests immortality in their death policy and in what way they communicate this to their users.

2. The digital self and online identities facing death

During our lifetime, we try to leave traces that persist after we are gone – the will is the most obvious example (Stokes 371). Sigmund Freud argues in “Beyond the Pleasure Principle” that the aim of life is death; meaning that through our whole lifespan we are preparing for this moment through living (Massimi and Charise 4). In the process, we experience numerous events, feelings and we share them with other individuals. And ironically this is exactly how Facebook works: While the traces of our lives used to be merely physical, now they have become more and more digital. For example, we don’t keep physical letters or photos but store these memories within our social media accounts – on our “Timeline”.

Thus, users create social media profiles that essentially resemble their offline identities, as they include components that resemble their offline relationships (Stokes 365). The “digital self” or “digital identity” are constructed and can only ever be an extended version of us, but they become an essential part of who we are – because as a consciously constructed version of us, they “extend our practical, psychological and even corporeal identity” (Stokes 363). And even if we die, these “digital identities” will stay alive, or possibly even keep on thriving: the “dynamic nature” (Brubaker, Hayes, and Dourish 158) of social media profiles can result in “interactive digital tombstones” (Brubaker, Hayes, and Dourish 158) because friends can still add content, enabling an “open-ended electronic wake” (Stokes 366).

The question then is how we will be remembered: Today, there are 5.54 social media profiles to be managed per person on average after one dies (Mander 201) – and only very few users decide in advance what ought to happen to these accounts. Therefore, it can be questioned how well we can be represented if we are not able to decide about the content anymore (Brubaker, Hayes, and Dourish 158), which does not leave aside the issue that through this form of memorialization only some an extension of the dead person themselves will be honored (Stokes 367).

2.1 Desire to be immortal

Yet, social media profile can fulfill a prevailing human desire to leave a meaningful trace, as we “unavoidably leave digital traces: […] our digital remains” (Wright 2). That implies that our constructed identities can eventually overcome death, as they are not tied to our biological life (Stokes 367). If we describe mortality as “an intrinsic and ongoing state over the entire lifespan of all persons” (Massimi and Charise 2), we realize that it is an “universal aspect of the human condition” (Massimi and Charise 4), making the desire to overcome it by becoming immortal understandable. This is not only about “the egoism of always wanting to be” (Gibson 66) but also about “wanting others to be and wanting always to be with others” (Gibson 66).

So, if profiles are memorialized (see 1.3), a certain form of “immortalization” becomes possible (Stokes 367), even though it cannot be understood as “immortality in the sense of unending life” (Overall 168) as human activities and experiences are no longer possible, but rather as a certain form of “containment” or “preservation” (Overall 168). Stokes argues in this context, that living on online “counts as me-surviving to at least some small degree” (Stokes 372) to others and that this persistent identity could make the death of the loved one “not-as-bad”, while also allowing to still interact and remember (Stokes 375). It could be seen as part of the “identity preservation strategies” in the sense of Unruh (341), who describes “sanctifying meaningful symbols” (like a Facebook profile) as part of maintaining the attachment to a deceased person (Brubaker, Hayes, and Dourish 153).

2.2 (Self-assigned) role of Facebook

How death in computing can be handled by being part of software planning has been part of various studies (Maciel 2011; Massimi and Charise 2009). As Maciel states, computing has not initially taken into account that users will die at some point. Thus, it is not surprising that Facebook introduced its death policy years after launching (McCallig 113) – providing an answer to the difficulty of handling deaths of users that directly corresponds with “identity preservation strategy” mentioned before: the digital identity will remain “largely intact” (Stokes 366). Therefore, Facebook can be seen as part of the notion of “preservationists”, who are in favor of passing a “digital legacy” on, rather than “deletionists”, who argue that the internet needs to learn how to forget, as Maciel puts it (4).

However, Facebook does not make users aware of these terms right when signing up but rather has designed default settings, for example introducing the “legacy contact” (s. chapter 3). The wording and how the settings are composed within the policy raises questions about how Facebook positions itself in our lives: it facilitates to expand our grief, taking it from the funeral into everyday-life (Brubaker, Hayes, and Dourish 156) and making a continuous form of relationship with the deceased possible (Wright 6). Still, that can also produce discomfort as developers and users are yet to “find a balance between expanded access to content and the appropriateness of engaging with that content in a particular context” (Brubaker, Hayes, and Dourish 156).

3. Analyzing Facebook’s Interface and its Death Policy:

Maciel expresses that computing was not designed thinking that users will eventually die (…), that is why it is interesting to take into account that Facebook introduced its first approach to deceased users in early 2015, specifically expressing the following (Maciel 4): “We hope this work will help people experience loss with a greater sense of possibility, comfort and support” (Facebook will let you pick someone to manage your account after you die n. pag.) wrote product manager Vanessa Callison Burch, content strategist Jasmine Probst and software engineer Mark Govea in the Facebook newsroom.

From the very moment a new user accepts Facebook’s terms and conditions, the process of gathering and collecting data starts; it begins with your email address, your name, birthdate, relationship status and pictures uploaded. Ironically Facebook works as a ‘timeline’ and its interface is designed to look as one. The social media platform started with calling its feed a wall, changing it then to the word timeline. This revamped version of the wall is a visual history of yourself, starting from the moment you were born (Parr n. pag.). This update is by far the most significant and it is decisive as it defines the new way we are going to interact with each other and with Facebook itself. The timeline introduces the Cover Picture and the Life Event, this one breaks down into work & education, family & relationships, home & living, health and wellness and travel & experiences, these events being milestones in the user’s lives; “It is fun and easy to fill out your timeline”, claims Zuckerberg.

The design of this timeline provides its users the proper affordances to follow the structure of it; beginning with the icon of a baby. This does not give a proper closure for this timeline, as it either keeps the profile of the deceased as open or memorialized, which can be interpreted as a suggestion of an immortal avatar of the user.

Figure 1: Own representation; Screenshot of a Facebook Timeline, 2017.

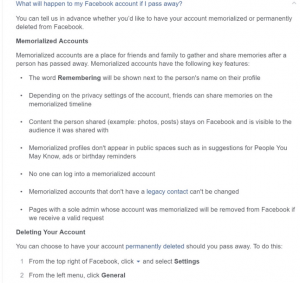

Using the interpretive policy analysis as a method to investigate the choice of words, phrasing and depiction of Facebook’s death policy, we will now have a closer look at the death policy itself. Facebook offers a question and answer architecture within its Help center (see fig. 2).

Figure 2: Own representation, Overview of Question and Answer architecture (Memorializing Accounts n. pag.)

This architecture of the website makes it easy for readers to find quickly what they are looking for. Not only can they see that they can change settings on what should happen to their own Facebook account, but also what steps to take if oneself is a Legacy Contact for someone else or how to request Memorialization for a friend or relative.

When opening these drop-down questions, one can see that the way the text is presented is, again, simplified by bullet points and enumerations (see fig. 3).

Figure 3: Own representation, Options of what will happen to a deceased person’s account (Memorializing Accounts n. pag.)

As can be seen already here, Facebook uses the word “legacy contact” for a person that is in charge after a deceased person had decided before who should be their legacy contact. This clearly shows a tendency towards the usage of words that are used in real life for describing what a person leaves behind (his or her legacy). Moreover, Facebook already suggests in the first question within its policy, that a Memorialization is possible. This arrangement proposes Memorialization as a way to handle a deceased person’s account instead of suggesting deleting it. That Facebook is not part of the “deletionists” movement, is shown by this array of options.

This can also be seen in the way a memorialized account and timeline is being handled: No content can be added or removed from the timeline, unless the legacy contact logs into the account. This person is still in charge of changing the profile picture, cover photo, writing a pinned post or answering new friend requests (Memorializing Accounts n. pag.).

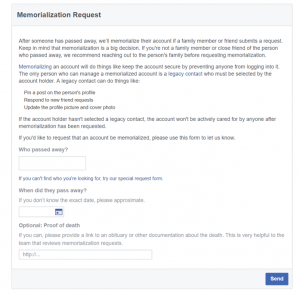

Further down in the line of questions and answers, Facebook gives instructions on how to memorialize an account or how to request deletion (see fig. 4).

Figure 4: Own representation, Requesting Memorialization (Memorializing Accounts n. pag.)

In this question and answer construct, Facebook again first addresses the Memorialization of an account. Additionally, the headline “Memorializing an account” can be found underneath the first question in this section. Comparing this to the question about deleting an account, one can see that such an eye-catching headline is nowhere to be found. This again proposes Facebook’s will to memorialize than to delete accounts. Furthermore, to request memorialization is a lot easier to do, than to request deletion. When clicking on “contact us”, in order to request memorialization, one is forwarded to a website with preset questions and answers to fill in (see fig. 5).

Figure 5: Own representation, Memorialization form (Memorializing Accounts n. pag.)

In contrast to requesting memorialization of an account, one does not need physical documents in this case. For deleting an account, one first needs at least one of the above-mentioned documents and can afterwards contact Facebook via the link “send us a request”. By using this link, one is forwarded to a similar website like the one when requesting memorialization, but with seven questions, instead of three. This shows a clear tendency to nudging people into memorialization rather than requesting deleting.

4. Conclusion

After applying the interpretive policy analysis, we can conclude that Facebook rather suggests memorializing an account than the deletion of this one. This is evident in several of their answers within their death policy explained on the website. Thus, Facebook tries to keep the deceased person with the help of a legacy contact in certain ways alive and present online. Therefore, this research project has found out that keeping someone alive in the online world is more favorable than deleting their profiles and content according to its platforms.

As explored in this paper, Facebook does prefer its deceased users to remain online and available; new data are being generated due to the interactions that these former users keep having with the living users they leave behind. The destination of this data remains private for Facebook’s confidentiality preferences, so we cannot determine if it is being handed out to third parties. Nonetheless, a further development in keeping somebody in whatever ways possible alive, can be expected in the future.

Works Cited

Brubaker, Jed R., Gillian R. Hayes, and Paul Dourish. “Beyond the Grave: Facebook as a Site for the Expansion of Death and Mourning.” The Information Society 29.3 (2013): 152–63. Print.

Carroll, E., and J. Romano. Your Digital Afterlife: When Facebook, Flickr and Twitter Are Your Estate, What’s Your Legacy? Pearson Education, 2010. Print.

Facebook will let you pick someone to manage your account after you die, 2015. Web. 20 Oct. 2017. <http://www.cbc.ca/news/technology/facebook-legacy-contact-can-keep-your-profile-updated-after-you-die-1.2954595>.

Gibson, Margaret. “Memorialization and Immortality: Religion, Community and the Internet.” Popular spiritualities: The politics of contemporary enchantment. Ed. Lynne Hume and Kathleen McPhillips. Aldershot, England, Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2006. 63–76. Print.

Maciel, Cristiano. “Issues of the social web interaction project faced with afterlife digital legacy.” Proceedings of the 10th Brazilian Symposium on Human Factors in Computing Systems and the 5th Latin American Conference on Human-Computer Interaction. Porto de Galinhas, Pernambuco, Brazil: Brazilian Computer Society, 2011. 3–12. Print.

Mander, Jason. Internet users have average of 5.54 social media accounts, 2015. Web. <http://blog.globalwebindex.net/chart-of-the-day/internet-users-have-average-of-5-54-social-media-accounts/>.

Massimi, Michael, and Andrea Charise. “Dying, death, and mortality.” CHI ’09 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 4/4/2009 – 9/4/2009. Boston, MA, USA: the 27th international conference extended abstracts. Ed. Dan R. Olsen. New York, NY: ACM, 2009. 2459. Print.

McCallig, Damien. “Facebook after death: An evolving policy in a social network.” Int J Law Info Tech 22.2 (2014): 107–40. Web. <https://academic.oup.com/ijlit/article-pdf/22/2/107/2398491/eat012.pdf>.

Memorializing Accounts. Web. 18 Oct. 2017. <https://www.facebook.com/help/1506822589577997/>.

Overall, C. Aging, Death, and Human Longevity: A Philosophical Inquiry: University of California Press, 2003. Print.

Parr, Ben. Facebook Timeline Redefines User Profiles, 2011. Web. 20 Oct. 2017. <http://mashable.com/2011/09/22/new-facebook-profiles/>.

Stokes, Patrick. “Ghosts in the Machine: Do the Dead Live on in Facebook?” Philosophy & Technology 25.3 (2012): 363–79. Print.

Unruh, D. R. “Death and personal history: Strategies of identity preservation.” Social Problems 30 (3) (1983): 340–51. Print.

Wright, Nicola. “Death and the Internet: The implications of the digital afterlife.” First Monday 19.6 (2014). Print.

Yanow, Dvora. Conducting Interpretive Policy Analysis. 2455 Teller Road, Thousand Oaks California 91320 United States of America: SAGE Publications, Inc, 2000. Print.