Drones Floating to Freedom

On a warm August night in the Dutch summer of 2018, I went for a stroll in the heart of my new home: Amsterdam. Arriving at the edge of the center, I found myself surrounded by thousands of people gathering along the river T’IJ. It seemed as though they were excited for something to appear in the air. As I followed the gaze of the mass, the sky suddenly lit up with a swarm of three hundred drones floating around like free birds …

Clip 1: Promotion Footage of Franchise Freedom

Franchise Freedom

The imagery in the sky turned out to be a new project by Studio Drift, called Franchise Freedom. For the first time, this Amsterdam based collective showcased their air-sculpture in Europe after the premiere in Miami. It marked for many a first real-life encounter with a new phenomenon: drone-sculptures The idea of using drones to form aesthetic patterns in the sky first captured the imagination of millions during the opening ceremony of the 2018 Winter Olympics in South-Korea. An absolute capstone of this new practice, and Guinness World Record, are the 1374 drones “dancing above Xi’an ancient city wall” in China.

Illustration 1: Drones above Xi’an’s Wall

Corporations like Intel and BMW are supporting these drone developments, enabling the artistic sculptures to become more and more intriguing. The Queen of Drones, an engineering grad from MIT named Natalie Cheung, argues for instance that “drone light shows extends the reach of art into the night sky, creating a whole new way for artists to connect with their audience” (Petrovic n. pag.). For the creators of Franchise Freedom, “The swarm as an autonomous organism expresses freedom, whilst the individual birds [symbolized by drones] have to adhere to strict rules in order not to fly against each other. The resulting image is a wonderful translation of how we live together as people and look for our own place inside or outside society” (Girst n. pag.).

Permission for Freedom

While Studio Drift’s drone-sculpture evoked abstract philosophical questions about the nature of freedom, the creators experienced the harsh reality of “freedom by strict rules” when trying to showcase their art. It turned out that the Dutch government has an extensive set of protocols and regulations, prohibiting drone flights above Amsterdam. The reaction to Studio Drift’s permission to exhibit their work was therefore equivocal. Many drone-users invested much time and money into getting a ROC-permit (a necessary license to fly drones) and never received this kind of clearance. On the one hand, the Dutch drone community is happy to see new infrastructural possibilities becoming reality, making the politicians rethink the airspace. On the other hand, this project made clear that the government’s drone policy has a long way to go, both in terms of clarification and conceptual rethinking (De Jager n. pag.).

Custers and Herman in The Future of Drone Use argue that the drone has mostly been perceived and theorized as a military artifact. However, they claim the technological developments in the field of drone flight call for a radical rethinking of the drone itself and its place in the air. To understand some of the frustration surrounding this rethinking of the drone Davis and Chouinard provide a useful explanation. They argue that in order to use an artifact, a user must (1) be able to perceive its functions, (2) have the dexterity to use it and (3) meet the cultural and institutional requirements (244-246). Looking at these three steps, it is clear that a new awareness and mastery of the drone is there; however, the rules stay behind. It is this discrepancy that frustrates the drone progress. The case of Studio Drift shows that a theoretical rethinking of protocols and regulations of the areal infrastructure is necessary.

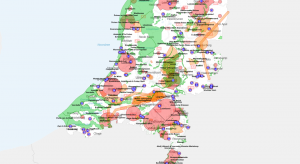

Mapping Freedom

Parks argues that the debates within media studies have focused too much on the production and reception, while a better understanding of the material infrastructure is indispensable (356). To effectively rethink the air infrastructure, a thorough understanding of how it should be mapped is needed. Therefore, Parks’ infrastructural approach focuses on “the material sites and objects involved in the local, national, and/or global distribution of audiovisual signals and data” (Stuff You Can Kick 356). Today, however, the map that the government uses for designating fly-zones (illustration 2) is based on a two-dimensional space that doesn’t take the altitude and temporality of flight infrastructures into account. Recently, in a study on drones, LaFlamme concluded that little has been written about how drones are/should be incorporated in the existing infrastructure (700). Part of the problem is that underneath the mapping problems of the infrastructure there are competing signals and data being used by the airplane and drone operators. As Parks highlights, this means one should not only focus on representational questions, but also needs to deal with “ownership, development, and access” (Around the Antenna n. pag.). This requires a move away from the standard two-dimensional map that now is supposed to visualize the drone infrastructure.

Illustration 2: Dutch Map of Fly Zones for Drones

Mattern follows Parks in arguing that it is the duty of infrastructural citizens to become aware of the systems that surround and how to properly use them (n. pag.). Mattern reiterates the significance of art in this process as it can “make the invisible visible” (n. pag.). Franchise Freedom quite literally illuminates the infrastructure of the sky. In addition, as McLuhan already pointed out, art also actively reshapes our surroundings, opening up new ways of interpretation and engagement (90). Franchise Freedom exposes the multifaceted use of our aerial infrastructure. It allows us to imagine the new visuals and signals of the infrastructure.

Future of Freedom

Franchise Freedom has reopened the infrastructural future of the sky; highlighting the importance of new infrastructural approaches in the debates surrounding drones. Following the Franchise Freedom motto of Studio Drift, self-determination is only possible within rules, thus it is important that we as infrastructural citizens get aware of the facts and the choices to be made. Only then are we able to float with our drones towards freedom.

References

Custers, Bart Herman Maria. The Future of Drone Use: Opportunities and Threats from Ethical and Legal Perspectives. The Hague: Asser Press, 2016.

Davis, Jenny L, and James B Chouinard. “Theorizing Affordances: From Request to Refuse. Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society 36.4 (2017): 241-248.

De Jager, Wiebe. “Droneshow voor het eerst in Nederland te zien.” Dronewatch. 2018. 17 September 2018. <https://www.dronewatch.nl/2018/08/07/ilt-geeft-groen-licht-voor-droneshow-amsterdam/>.

Girst, Thomas. “300 drones illuminating the river IJ in Amsterdam – Studio Drift to present European premiere of “FRANCHISE FREEDOM”. After world premiere in Miami Beach in collaboration with BMW, airborne performance on August 10 – 12, 2018.” BMW Group. 8 August 2018. 17 September 2018. <https://www.press.bmwgroup.com/global/article/detail/T0283561EN/300-drones-illuminating-the-river-ij-in-amsterdam-%E2%80%93-studio-drift-to-present-european-premiere-of-%E2%80%9Cfranchise-freedom%E2%80%9D-after-world-premiere-in-miami-beach-in-collaboration-with-bmw-airborne-performance-on-august-10-%E2%80%93-12-2018?language=en>.

Good Morning America. “High-tech drones steal the show at the Winter Olympics.” YouTube. 10 February 2018. 18 September 2018.<https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yRMUNptyTag>.

Intel. “Intel’s 500 Drone Light Show | Intel.” YouTube. 4 November 2016. 18 September. <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aOd4-T_p5fA>.

Intel. Commercial Drones from Intel. Santa Clara: Intel. 18 September 2018. <https://www.intel.com/content/www/us/en/drones/drone-applications/commercial-drones.html>.

LaFlamme, Marcel. “A Sky Full of Signal: Aviation Media in the Age of the Drone.” Media, Culture & Society, 40.5 (2018): 689–706.

Mattern, Shannon. “Infrastructural Tourism.” Places Journal (2013). 17 September 2018. <https://doi.org/10.22269/130701>.

McLuhan, Marshall. “The Emperor’s Old Clothes.” The Man-Made Object. Ed. Georgy Kepes. New York: George Braziller, 1966. 90-95.

Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management. Drone. The Hague: Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management, 2015. 18 September 2018. <https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/onderwerpen/drone>.

New China TV. “New record! 1,374 drones dance over ancient city wall of Xi’an.” YouTube. 2 May 2018. 18 September 2018. <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_U6jIYroUck>.

Parks, Lisa. ““Stuff You Can Kick”: Towards a Theory of Media Infrastructures.” Between Humanities and the Digital. Eds. Patrik Svensson and David Theo Goldberg. London: The MIT Press, 2015. 355-373.

Parks, Lisa. “Around the Antenna: The Politics of Infrastructural Visibility.” Flow (2009). 20 September 2018. <http://www.flowjournal.org/2009/03/around-the-antenna-tree-the-politics-of-infrastructural-visibilitylisa-parks-uc-santa-barbara/>.

Petrovic, Karli. “Queen of Drones: Revolutionizing Night Sky Light Shows.” Intel. 18 September 2017. 18 September 2018. <https://iq.intel.com/queen-of-drones-revolutionizing-night-sky-light-shows/>.

Studio DRIFT. “Franchise Freedom – a flying sculpture by Studio Drift in partnership with BMW.” Vimeo. 2 February 2018. 17 September 2018. <https://vimeo.com/253934552>.

Studio DRIFT. Studio Drift Amsterdam. 17 September 2018.<http://www.studiodrift.com/franchise-freedom/>.