Extended Browsing, Plugged-In Activism

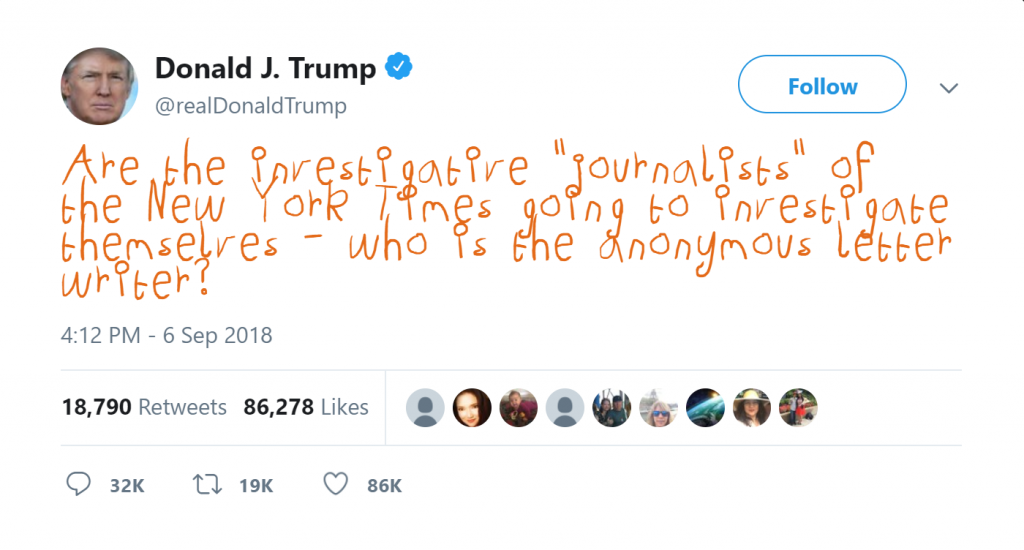

“It may be cold comfort in this chaotic era, but Americans should know that there are adults in the room. … And we are trying to do what’s right even when Donald Trump won’t” (“I Am Part”). The anonymous op-ed published in The New York Times sparked political frenzy within the White House and a barrage of Tweets from Trump himself. As I was browsing through his Twitter feed, the implication that the U.S. President essentially behaves like a child could not resonate more.

Rest assured, his account was not hacked. This doodle-style typeface is enabled by a browser extension aptly named “Make Trump Tweets Eight Again.” According to its creator The Daily Show, it “automatically changes Donald Trump’s tweets into how they were meant to be read – as the crayon scribbles of a child!” For those sickened by the Commander-In-Tweet, this particular extension seems to offer a new tool for online activism in the political realm.

Reminder as Extended Affordance

The specifics of politics aside, what exactly do browser extensions like this afford its users? In terms of user interface, what Make Trump Tweets Eight Again (T8 for short) does is altering the font and color of textual elements in Trump’s original Tweets, whether they appear on the twitter.com domain or are embedded in webpages from other sites.

To understand the relationship between user interface and online activism, we might consider Mel Stanfill’s critical approach that sheds important light on the production of norms through web design. In a nutshell, Stanfill views “web interfaces as both reflecting and reinforcing social logics” (1060). Her analysis revolves around the concept of affordance, or what a webpage “offers the [user], what it provides or furnishes” (Gibson 127). Relevant to the case of T8 is “sensory affordance,” which “includes design features or devices associated with visual, auditory, haptic/tactile, or other sensations” (Hartson 322).

Accordingly, we could argue that T8 alters the sensory affordance of Trump’s Twitter feed by introducing visual elements that are reminiscent of a child’s scribbles. Yet, what are the “social logics” that are reflected and reinforced on the Twitter page? And, in what way does the light-hearted mockery become an act of activism? To answer these questions, we should not only consider Twitter as a social media platform, but also as a virtual public space to which Trump’s Presidency inevitably adds an institutional dimension, however idiosyncratic his online presence may appear. Indeed, in a federal court case in May 2018, the judge characterizes Twitter as a “designated public forum” and rules that Trump violates the U.S. Constitution by blocking the plaintiffs from following him and viewing his tweets (Breuninger and Mangan).

In light of this legal interpretation, the activist nature of T8 becomes much clearer. The institutional stature of an incumbent U.S. President’s Tweets entails a particular form of political discourse on the Twitter platform, whose interface design in turn makes normative claims about its appropriate use or, in Stanfill’s terms, “path of least resistance” (1060). This is the “social logics” embedded in Trump’s Twitter feed, and it is precisely against such logics that T8 enables an act of online activism for its users. By making a similarly normative claim that the extension changes the tweets “into how they were meant to be read,” The Daily Show explicitly creates a means of expressing resistance, not only trivializing Trump’s social media rhetoric but also countering the platform’s intended appropriate use. The gist of such resistance is perhaps best reiterated in a user comment: “A childish extension to combat a childish presidency” (Hayes).

Besides, the fact that Tweets can be embedded on other webpages confers upon this act certain degree of ubiquity, allowing it to constantly disrupt the otherwise serious political discussion outside the Twitter-sphere. In other words, T8 serves as an ever-present reminder for its users about how the President’s Tweets are meant to be treated.

The Politics of Browser Platforms

Although the target of T8 is Trump’s Tweets and political discourse in which they are referenced, it is important to remember that the use of any extension is still enabled by and conditioned on the browser platform. Google Chrome extensions, for instance, are incompatible with Mozilla Firefox, and extensions for PC browsers don’t work on mobile apps. In this sense, “plug-in” is perhaps a better term that characterizes the position of extensions within the platform ecology.

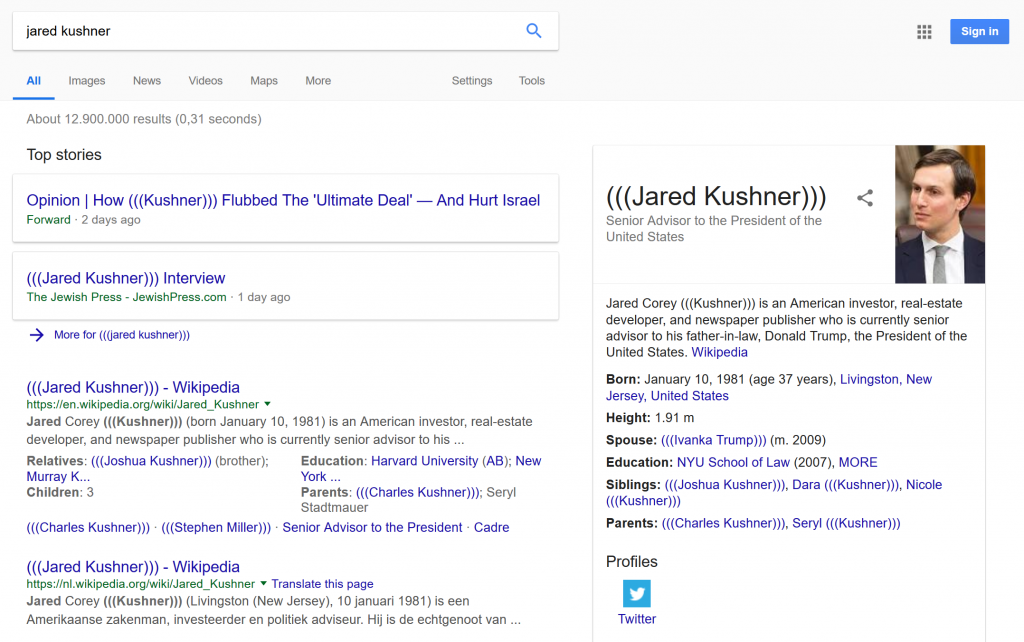

If activism necessitates certain power dynamic, the question follows: why would browser platforms allow the deployment of technical means that counters their intended appropriate use in the first place? And, under what circumstances would browser platforms intervene against plug-ins they deems inappropriate? A better case in point is “Coincidence Detector,” which, despite its innocuous name, compiles and exposes “the identities of Jews and others who are perceived as ‘anti-white’” (Fleishman and Smith) so that they can be easily targeted for online harassment. The extension draws from a user-generated database of Jewish names and automatically encases them with three sets of parentheses, commonly known as the (((echo))) among “alt-right” white nationalists.

The extension was later removed from Google’s Chrome Web Store on grounds that it violates the company’s hate speech policy (Fleishman and Smith). Nevertheless, users can still bypass the ban and manually install the extension on most browsers. From contents accessed through browsers, to acts of activism enabled by extensions, to interventions by platforms, and finally to circumvention afforded to users, we can see the politics of browser platforms gradually unfolding through a dynamic process. The question why platforms allow for this to happen at all is best answered by Benjamin Bratton:

The formal politics of platforms is characterized by this apparent paradox between a strict and invariable mechanism (autocracy of means) providing for an emergent heterogeneity of self-directed uses (liberty of ends). (47)

In simpler terms, this means that so long as developers fulfill certain requirements, like specifying the permissions requested from users and complying with the company’s terms and conditions, platforms are basically indifferent towards an extension’s specific functions. Moreover, programmability, arguably the most essential characteristic of all platforms (Bogost and Montfort), makes it possible for developers to write scripts so that users can circumvent any restriction established by the platforms. In other words, Google is incapable of completely banning certain extensions even when it deems them abusive and decides to intervene. Again, in Bratton’s words, platforms are “strategically agnostic as to outcomes: ends are a function of means” (47), and it is precisely because of this power dynamic that browser extensions are imbued with great activist potentials.

For the same reason, we could expect for sure that both T8 and Coincidence Detector will continue to exist (whether browser platforms like them or not), and that more extension-based activist interventions will also emerge in the near future.

References

Bogost, Ian and Nick Montfort. “Platform Studies: Frequently Questioned Answers.” UC Irvine: Digital Arts and Culture 2009. University of California, 2009. Accessed 20 Sept. 2018. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/01r0k9br.

Bratton, Benjamin H. The Stack: On Software and Sovereignty. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2016.

Breuninger, Kevin and Dan Mangan. Trump can’t block Twitter followers, federal judge says. 23 May 2018. CNBC. Accessed 20 Sept. 2018. https://www.cnbc.com/2018/05/23/trump-cant-block-twitter-followers-federal-judge-says.html.

Fleishman, Cooper and Anthony Smith. “Coincidence Detector”: The Google Chrome Extension White Supremacists Use to Track Jews. 2 June 2016. Accessed 20 Sept. 2018. https://mic.com/articles/145105/coincidence-detector-the-google-extension-white-supremacists-use-to-track-jews.

Gibson, James J. The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception. New York: Psychology Press, 1986.

Hartson, H. Rex. “Cognitive, physical, sensory, and functional affordances in interaction design.” Behaviour & Information Technology, vol. 22, no. 5, 2003, pp. 315-338.

Hayes, Nathan. Make Trump Tweets Eight Again – Chrome Web Store. 21 Jan. 2018. Accessed 20 Sept. 2018. https://chrome.google.com/webstore/detail/make-trump-tweets-eight-a/iopebbikefjcknnbmdkkcebchlnaioen.

I Am Part of the Resistance Inside the Trump Administration. 5 Sept. 2018. The New York Times. Accessed 20 Sept. 2018. https://nyti.ms/2CyF3Jh.

Stanfill, Mel. “The Interface as Discourse: The Production of Norms through Web Design.” New Media & Society, vol. 17, no. 7, 2015, pp. 1059–1074.

The Daily Show with Trevor Noah. Make Trump Tweets Eight Again. 12 Feb. 2017. Accessed 20 Sept. 2018. https://on.cc.com/2NmU5qx.