Is your personal safety app keeping you safe?

The World Health Organization (WHO) reports, “one in three women globally have been sexually or physically abused- amounting to some 800 million people world-wide.” [1] One of the tools gaining acceptance among women to help prevent harassment is ‘Safetipin: Personal Safety & Women’s Safety App.’

Source: http://safetipin.com/media/42/safer-city-project-prepares-to-launch-safetipin-app/

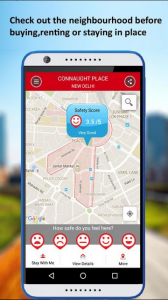

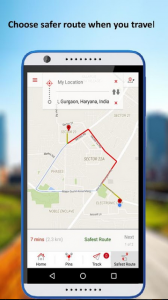

Like the name suggests, Safetipin offers users safety-related information based on location. By permitting the app to run in the background, users get alerts with the ‘safety score’ of areas they enter. They can then decide whether they want friends to track them. Users are also permitted to view alternative routes before selecting the safest one.

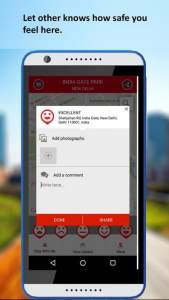

To calculate the ‘safety score’, users are encouraged to become active participants. They are asked to contribute to the safety-related information by sharing sentiments along predetermined parameters such as lighting, visibility, diversity, crowd, public transport, walk path, security, openness, and feeling.

Safetipin seems to be a pertinent app for women. I can understand the peace of mind and sense of security it can offer. However, I see the app as a security blanket, much like the ones we had as children; the “blankey” which we believed kept the “monsters” at bay.

But does this security blanket offer protection in reality or only in theory?

Source: Screenshots from the Play StoreThe images from the Play Store undoubtedly communicate the ease of use and the functionality of the app. According to J.B. Fogg, “Persuasive technologies can adjust what they do based on user inputs, needs, and situations.” [2] And Safetipin does just that through user participation. The app persuades users to share their opinions of places in real time, to ensure app information is up-to-date. Crowd sourced data, i.e., data from a collective inspires confidence and assures users that they have access to apt information- based on data aggregated from people just like them. Hence, an overview of the app has the power to persuade users to install it.

But is Safetipin using user observations to solely update safety-related information?

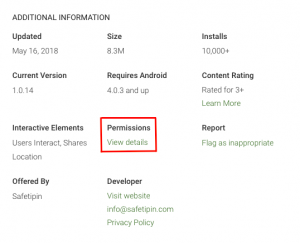

Source: Screenshot from the Play Store

Prior to installing Safetipin, if you take the time to read the ‘Additional Information’ under ‘Permissions’, you will find “monsters” hiding in plain sight. When users install the app, they agree to grant the app permission to get access to:

- Your identity & find accounts on your device

- Read your contacts

- Your location which are “approximate locations (network based)”, “precise location (GPS and network based)”, “Access extra location provider commands”

- Your Photos/Media/Files which includes “permissions to read the contents of the USB storage, and to modify or delete the contents of your USB storage”

- To “receive data from the internet, view network connections, full network access, use accounts on the device, prevent device from sleeping, read Google service configuration”

And if that wasn’t enough there is a disclaimer at the end which states, “Updates to My Safetipin: Personal Safety & Women’s Safety App may automatically add additional capabilities within each group. Learn More.” [3]

Upon reviewing the app on the Play Store, it certainly feels like Safetipin is that security blanket.

Evidently, Safetipin is not merely interested in providing ‘safety-related information.’ They want to know everything they can know about their users. Making Safetipin a security blanket in theory.

And this brings us to ask why?

Safetipin possesses the ability to track “social action” along with “online quantified data” in real-time. This allows for predictive analysis, making the aggregated metadata accurate and current. It is no surprise “platform owners routinely share users’ aggregated metadata with third parties for the purpose of customized marketing in exchange for free services.” (Van Dijk, 2014) [4] While, Safetipin endeavors to keep users safe, the app remains a business with economic motives.

This would not be possible if the app did not provide a location based service. While users recognize they are sharing their location, the consequences of doing so might escape them. According to Carlo Barreneche, “The significance of location is far greater than just the access of information through online maps. Location and the nearby environment are becoming prominent for our communications at different levels.” [5] This is a reason why we have seen a tremendous upsurge in the “geo-web.”

As Safetipin encourages its users to tag with geographic information, users are placing information into ready categories. “Categorization is a powerful semantic and political intervention: what the categories are, what belongs in a category, and who decides how to implement these categories in practice, are all-powerful assertions about how things are supposed to be.” says Bowker and Star. [6] Users, however, are not privy to this information.

What are the ethical dilemmas which arise from data tracking?

The discourse around data tracking and ethics is arguably subjective. Hence, the line between ethical and unethical is blurry.

Users consider lack of information unethical. This includes not knowing what data is being collected, who is collecting data and how data is used. But, business owners can argue that the users consented when agreeing to the terms & conditions prior to installing the app.

Additionally, there are concerns around data collection being misused. In many cases, business owners have felt little to no consequences. For instance, “Cambridge Analytica’s psychographic targeting demonstrates how companies can psychoanalyze us and craft intentionally manipulative messages at massive scale. They can use that data in unlimited ways. And if someone breaks in and steals that data, they are not responsible – just ask Equifax.”[7]

History is filled with examples and if we look at the present I am sure we will find many more. “Marc Rotenberg of the Electronic Privacy Information Centre noted that misuse and abuse of data are not a new problem.” [8] Yet, there seems to be little movement where action is required.

“Greg Skibiski of Sense Network believes we need a “New Deal on Data” By this he means that the end user should be able to own their data and decide how it should be used. This should apply to “any data that we can collect about you and metadata that we make out of it”, he said. He also urged that “data should have a life span, so that it is routinely purged after a given time period. Otherwise data that is saved is more likely to be abused.” [9]

I too believe that we need a “New Deal on Data”- the power to choose how our data is going to be used, and who is going to be using it. Data misuse could be prevented by giving data a lifespan. This perspective could spark debate and possibly arrive at a solution so that we are safe in the truest sense.

Works Cited:

[1] Margit, Maya. “Don’t Panic: India Tackles Women’s Safety with Technology”, http://www.themedialine.org/news/don’t-india-tackles-womens-safety-with-technology

[2] Fogg, B.J. Persuasive Technology: Using Computers to Change What We Think and Do. San Fransisco, Morgan Kaufmann Publsihers, 2003, p6

[3] Google Play Store. “My Safetipin: Personal Safety & Women’s Safety”, play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.safetipin.mysafetipin&hl=en

[4] Van Dijk, José. Surveillance & Society- Datafication, Dataism and Dataveillance, 2014, p197

[5] Carlos, Barreneche. Carlos. Governing the geocoded work: Environmentality and the politics of location platforms, 2010, p332

[6] Gillespie. Tarleton. The Relevance of Algorithms, 2014, p5

[7] Laboy, Deb. “Marketers, Data Collection and the E-Word: Ethics”, cmswire.com/digital-marketing/marketers-data-collection-and-the-e-word-ethics/

[8] David Bolier, David. The Promise and Peril of Big Data. Washington, DC, The Aspen Publisher, 2010, p33

[9] ] David Bolier, David. The Promise and Peril of Big Data. Washington, DC, The Aspen Publisher 2010, p36