Selling Sexualities: The ethical implications of Grindr’s new advertising tool

The gay dating app Grindr is trying to reinvent itself. In a mission to leave behind its image as a hookup platform, Grindr Inc. has launched several new projects, including the LGBT-themed magazine INTO, anti-discrimination campaign Kindr, and the inclusion of transgender users. And yet, the most significant innovation is Grindr’s new advertising product, not for its novelty, but for its problematic ethical implications.

Upon a first glance, the new product – launched in August 2018 – doesn’t sound too different from similar projects by other platforms: The app collects its user data in order to sell it to potential advertisers, who can then target the users directly, within the app itself or on other mobile sites or apps. In fact, this so-called platform capitalism has been a popular marketing tool for years. Grindr now goes one step further: eliminating the intermediaries and launching a self-serve advertising product, “providing all advertisers direct access to the enormous spending power of the LGBTQ+ community”.[1]

Problematic implications

The problematic aspect lies in the very nature of Grindr. As Kitchin points out, some data could be considered harmless, while other data, closely related to individuals, can be highly sensitive.[2] Analyzing and sharing this data has the potential to infringe on the individuals’ privacy and other human rights, actively sorting them out and potentially causing harm. This harm is not simply a question of privacy infringement. With Grindr catering to a LGBT userbase, the mishandling of their data could have significant real-world implications for users: As of 2018, homosexuality is still a crime in 72 countries, with ten of those even imposing the death penalty.[3]

And those implications are not merely an abstract scenario: In 2017, reports emerged of Egyptian police using Grindr to find and arrest gay men[4]. And earlier this year, Grindr was back in the headlines: A data leak exposed thousands of Grindr profiles including usernames, locations and HIV status, making those details personally identifiable.[5]

Emotional capitalism as a business model

The use of dating apps for capitalist goals is nothing new; dating apps represent a substantial sector of the so-called app-economy.[6] Its users share a large amount of social data with the app, often connected to geo-location services, allowing developers to easily monetize on this database for targeted behavior-based advertising.

From this commercial standpoint, the idea of capitalizing on a gay demographic is sensible: Gay men have historically had as affluent, making them an attractive customer base for targeted advertising. Established services like Gay Ad Network have been catering to this niche for years, filtering out and assembling gay user databases in order to sell them to advertisers – allowing a direct targeting of gay users on dating apps and beyond.

Gay Ad Network publicity.

Dating apps are a prime example of how intimacy is no longer practiced privately, but as part of the public sphere with performative aspects.[7] Users now publicly share data that used to be considered too intimate – and this once private information can subsequently be harvested for advertising purposes. Illouz calls this phenomenon emotional capitalism: Capitalism fostering the blurring of boundaries between public and private, between the emotional and the economic.[8]

Public vs. private

Those blurred boundaries are precisely what Grindr used as a defense after the data leaks. “It is important to remember that Grindr is a public forum”, states Grindr CEO Scott Chen in a blog post. According to Chen, the data users share is made public through this very act of sharing. This is problematic: as Boyd/Marwick point out, “the loss of privacy occurs when the context shifts away from how the information was originally intended”.[9] Grindr users share this data for their profile, not for advertising.

Not just that, but gay social life falls on a different place in the private/public spectrum. Grindr can be understood as a digital translation of cruising: gay men looking for non-committal sexual encounters in public places.[10] Cruising as a form of gay socializing has always been characterized by anonymity, despite its public forum – which is also applicable to Grindr. The very nature of its profiles and usage positions the app as less of a social media and more of a sexual one.

Social media or sexual media?

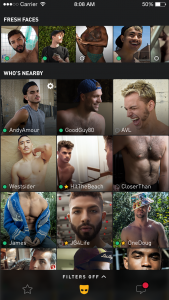

Grindr user interface.

Sexual media in this context is meant to distinguish Grindr from other social media platforms like Facebook or LinkedIn. The goal of a Grindr user is not primarily the connection and interaction with personal friends and business contacts, but easy sexual gratification based on proximity. As Roth remarks, the vast majority of Grindr users see the app as a “pure, single-function tool for facilitating hookups, not a social center for chatting and making friends.”[11]

Most users do not include their real name or face in the profile. Like in cruising, anonymity is upheld; the only information shared are relevant criteria for sexual compatibility, like sexual position, body type and HIV status.

The fact that Grindr encourages its user to supply this sexual information shows that the company is aware of this and actively caters to these objectives.

Highly sensitive information like one’s HIV status, after all, is something rarely included in other social media forums; in a sexual context, however, it is a necessary factor for HIV prevention – akin to condom use in the days of the 1980s AIDS crisis.[10]

The ethical fringes of capitalism

The problem in all this lies within the commercialization of this data. Gillespie explains how social media enterprises collect user data to construct what he calls “shadow bodies” – profiles based on online activity, emphasizing some aspects, while overlooking others.[12]

In the sexual context of Grindr, these shadow bodies emphasize sexual preferences and health status to a large degree, while overlooking almost all general or public information (because it wasn’t shared by the user). Using this shadow body for advertising purposes is therefore not only based on a misrepresentation, but actively publicizes the most private and intimate details of the user, which were consciously not included in other social media.

With Grindr’s troubling history of data leaks, the voluntary selling of user data for profit makes their new advertising tool inherently problematic. As long as public homosexuality and HIV status can be a death sentence, it is problematic to choose emotional capitalism over users’ physical safety. In the words of Boyd/Crawford, “just because it is accessible does not make it ethical”[13] – a phrase that Grindr would be wise to heed.

Notes

[1] BusinessWire. “Grindr, in Partnership with Bucksense, Launches Self-Service Advertising Product.” Business Wire, https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20180829005147/en/

[2] Kitchin, Rob. The Data Revolution: Big Data, Open Data, Data Infrastructures & Their Consequences. SAGE Publishing, 2014

[3] Duncan, Pamela. “Gay relationships are still criminalized in 72 countries, report finds.” The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/jul/27/gay-relationships-still-criminalised-countries-report

[4] Jankowicz, Mia. “Jailed for using Grindr: homosexuality in Egypt”. The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/global-development-professionals-network/2017/apr/03/jailed-for-using-grindr-homosexuality-in-egypt

[5] Burns, Janet. “Report Says Grindr Exposed Millions Of Users’ Private Data, Messages, Locations”. Forbes, https://www.forbes.com/sites/janetwburns/2018/03/29/report-says-grindr-exposed-millions-of-users-private-data-messages-locations/#4664b39b5c4c

[6] Albury, Kath et al. “Data Cultures of mobile dating and hook-up apps: Emerging issues for critical social science research.” Big Data & Society, vol. 4, no. 2, 2017, 1-11, doi:10.1177/2053951717720950

[7] Hjorth, Lim and Sun Sun Lim. “Mobile intimacy in an age of affective mobile media.” Feminist Media Studies, vol. 12, no. 4, 2012, pp. 477-484, doi:10.1080/14680777.2012.741860

[8] Illouz, Eva. Cold Intimacies: The Making of Emotional Capitalism. Polity, 2007

[9] De Souza e Silva, Adriana and Jordan Frith. Mobile Interfaces in Public Spaces: Locational Privacy, Control, and Urban Sociability. Routledge, 2012

[10] Race, Kane. “Click here for HIV status: Shifting templates of sexual negotiation.” Emotion, Space and Society, vol. 3, no. 1, 2010, pp. 7-14. doi:10.1016/j.emospa.2010.01.003

[11] Roth, Yoel. “Zero Feet Away: The Digital Geography of Gay Social Media.” Journal of Homosexuality, vol. 63, no. 3, 2016, pp. 437-442. doi:10.1080/00918369.2016.1124707.

[12] Gillespie, Tarleton. “The Relevance of Algorithms”. Media Technologies: Essays on Communication, Materiality, and Society (Inside Technology), edited by Tarleton Gillespie et. al. MIT Press, 2014, pp. 167-195

[13] boyd, danah and Kate Crawford. “Critical Questions for Big Data”. Information, Communication & Society, vol. 15, no. 5, 2012, pp. 662-679. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2012.678878