The Elephant in the Room: Privacy and Zoo Animals (and Humans Too)

ABSTRACT – Would you want your whole life broadcasted, without you knowing it? Thankfully, humans have rights protecting this from happening. As concern over privacy grows, paradoxically the trend to watch other animals online increases. Are we biased when it comes to privacy? Or is there more than meets the eye…?

The Amersfoort Zoo cares about privacy. Distributing dinosaur face masks this September, it helps visitors to enjoy their day at the zoo, without being recognizable when filmed or photographed by others and the material is

shared online (Ad.nl).[1]

It hereby reacts to an ongoing concern to control what gets shared by whom and who gets access to that material (Brandtzæg, Lüders and Skjetne 1006-1007). After all, privacy is important and should be protected.

Weirdly, that same zoo makes visual content of elephants and kasuaris available to watch online whenever one pleases. On the elephants there are four(!) different cameras, making it more likely they are visible on at least one of them. The zoo thus cares for privacy, but only when it concerns visitors. Indeed, as media scholar Brett Mills contends, privacy is a right that is hardly if ever extended to animals other than the human one. Moreover, it is actually something that should be overcome; something to conquer (Mills 196), often by means of ever newer technologies. ZooCam fits in perfectly.

Streaming Zoo Animals

The ZooCam is the “zoological analogue to CCTV” (Burke 71), a livestream which users can access to see camera footage of one or more animals in their confinement in a zoo (Burke 65-66). This can be an always available stream, as is the case in Amersfoort. There are also zoos that provide more limited access (within a specified time slot), or only in case of an important life event, e.g. with the birth of a young or a birthday (see for example omroepgelderland.nl).

You could ask how watching a zoo animal via live stream is different from watching it at the zoo. It is true that in both cases the animal can be seen by human eyes. What is different is that the animal can see the human when it visits the zoo, but the human is imperceivable for the animal if he watches via the ZooCam. This may sound like a trivial fact, but it is not.

Video: Clip taken from Bert Haanstra’s 1961 film Zoo.

If the zoo animal does not know that he is being watched, since the animal watching him cannot be perceived, he cannot act upon this knowledge to accordingly hide from sight (Gibson 136). Although the camera may be seen by the zoo animal, chances are high that the animal does not know what it affords human animals. With Gibson, among others, affordances of an artifact are highly dependent on the user, and are certainly animal-specific (Gibson 127). The zoo animals would have insufficient knowledge about the affordances of the camera to man (Davis and Chouinard 245), and therefore cannot circumvent what the camera requests of them. Zoo animals can however stay out of sight of the camera without knowing what the camera does (Burke 71), for there are places where the human gaze (Malamud 6) is not allowed. Bear in mind that this is mostly defined by human actors, gatekeepers in the literal and figurative sense, as well (Bruns 31).

As ZooCams provide lucrative business models (Burke 69), it is likely that visibility of the animals is beneficial for the zoo, and therefore something to strive for. As users come to the website of the zoo to watch the animals they want to see, it drives traffic towards that site. Being able to see the animal you wanted to see, makes you probably want to stick around on the page.

Edinburgh ZooCam

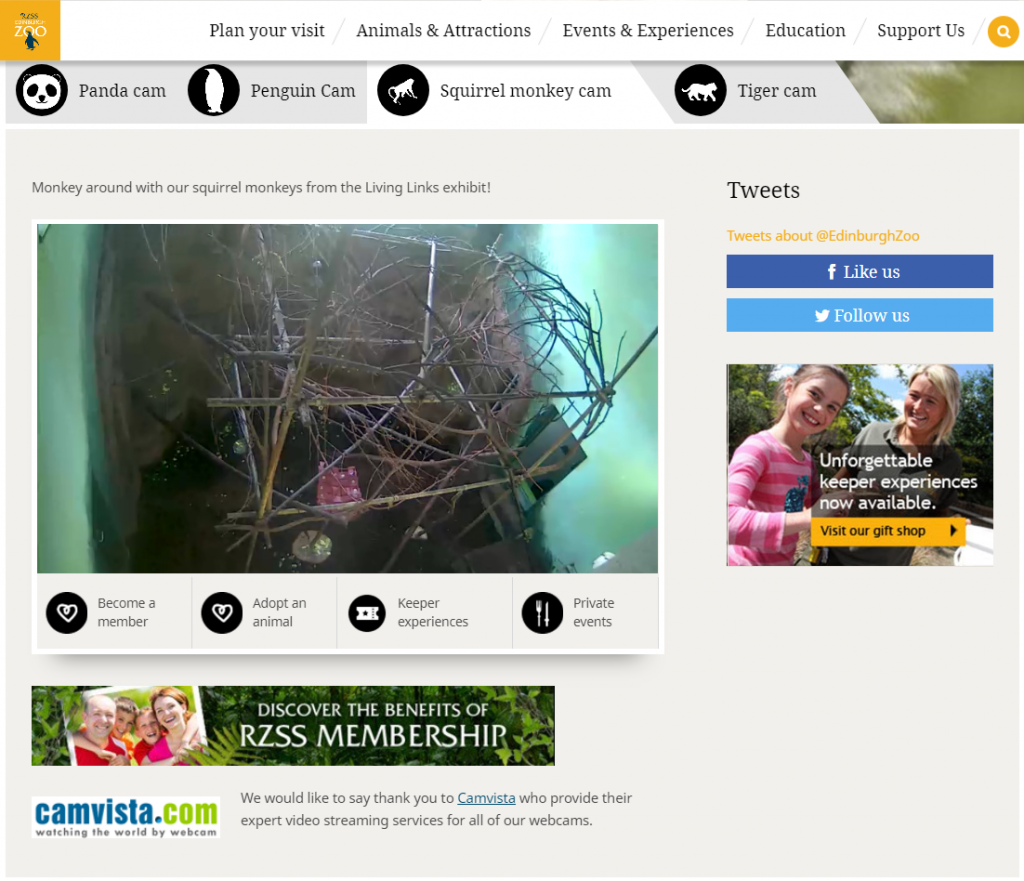

Different zoos enable different kinds of actions on their pages. I found the cams at Edinburgh Zoo to be interesting for the multitude of actions one can take. My example will be the page with the squirrel monkey cam. Other webcam pages are very similar, the most notable difference is one ad that either asks you to become a member or to buy a gift.

Image: Page with squirrel monkey cam from Edinburgh Zoo.

When looking at the page, it is striking how much more you can do than just watching. You can click on ‘become a member’ or the ad that reads ‘discover the benefits of RZSS membership’, which redirects to a page where you can sign up for membership, giving access to the zoo grounds the whole year round. Alternatively, you can ‘adopt an animal’. Various types of adoption are available of over 200 species the zoo houses. These types correspond to different amounts of money to be transferred, and different rewards to be gained. Another way to spend your money is by following the ‘keeper experiences’ link and/or ad. This then redirects to a page where you can buy a rich amount of ‘behind the scenes’ experiences. If you really want to spend the big bucks, you can opt for the option ‘private events’.

Interestingly, all these buttons and ads ‘interpellate’ (hail) the viewer as a consumer who may or better yet – should – be interested in spending money for various types of rewards and/or experiences (Stanfill 1063; 1066). It seems that the visual content of the animal is the ‘free lunch’ that draws you in, and once you are on there, encourages you to spend money anyway.

Moreover, it is not only after your cash, but also after your data, the currency of the digital age (Van Dijck 197-198). Using the tracker tracker tool, on the URLs that you are redirected to when clicking on the four buttons directly listed under the camera footage, shows sixteen trackers defined as ‘widget’, ten trackers labelled as ‘ad’, four in the category ‘analytics’ and two in ‘tracker’. Maybe humans are not as privileged when it comes to privacy after all…

Conclusion

Privacy is a highly human concept that is rarely if ever applied to animals, let alone zoo animals. As living exhibits it is part of their attraction to be visible for human visual consumption. This logic is taken to its extreme with the advent of ZooCams. This livestream is a means to see the zoo animal without having to visit zoo grounds, for it is available online on the website of the zoo. Although this makes for the zoo animals to be unable to see the humans watching them, it does not mean that the humans themselves are not being watched as well. However not by the zoo animal, but by trackers. The page encourages multiple strings of action that conclude to the same goals: gaining money and gaining personal data.

————————————————————————————————————————————————

[1] It turned out to be a promotional stunt to gain more awareness of an upcoming event called ‘DinoAdventures’ (nrc.nl). I hold that the example still provides food for thought.

————

List of References

Brandtzæg, Petter Bae, Marika Lüders and Jan Håvard Skjetne. “Too Many Facebook “Friends”? Content Sharing and Sociability Versus the Need for Privacy in Social Network Sites.” International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction 26.11-12 (2010): 1006-1030.

Bruns, Axel. “Gatewatching, Not Gatekeeping: Collaborative Online News.” Media International Australia 107.1 (2003): 31-44.

Burke, Andrew. “Zootube: Streaming Animal Life.” The Zoo and Screen Media. Eds. Michael Lawrence and Karen Lury. New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2016. 65-83.

Davis, Jenny, and Davis Chouinard. “Theorizing Affordances: From Request to Refuse.” Bulletin of Science, Technology and Society 36.4 (2016): 241-248.

Dijck, José van. “Datafication, Dataism and Dataveillance: Big Data Between Scientific Paradigm and Ideology.” Surveillance and Society 12.2 (2014): 197-208.

“Dinomaskers voor privacy van dierentuinbezoekers.” Ad.nl. 2018. De Persgroep Nederland. 20 September 2018. <https://www.ad.nl/amersfoort/dinomaskers-voor-privacy-van-dierentuinbezoekers~a0d13235/>.

“Geboorte neushoorn in Burgers’ live te volgen.” Omroepgelderland.nl. 2018. Omroep Gelderland. 20 September 2018. < https://www.omroepgelderland.nl/nieuws/2306472/Geboorte-neushoorn-in-Burgers-live-te-volgen>.

Lonkhuyzen, Lisa van. “Wil je niet op de foto? Zet dinomasker op.” Nrc.nl. Ed. Peter Vandermeersch. 2018. NRC. 20 September 2018. <https://www.nrc.nl/nieuws/2018/09/12/wil-je-niet-op-de-foto-zet-dinomasker-op-a1616326>.

Mills, Brett. “Television Wildlife Documentaries and Animals’ Right to Privacy.” Continuum 24.2 (2010): 193-202.

Stanfill, Mel. “The Interface as Discourse: The Production of Norms Through Web Design.” New Media and Society 17.7 (2014): 1059-1074.