Accept all Cookies

When the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) came into effect in the European Union in May 2018, its biggest impact for me as a web user was the scores of GDPR emails in my inbox and cookie consent requests on every website I visited. The incessant demands to accept cookies on the European internet, the design of the requests and the legislation behind them are the subject of this post.

GDPR was the first major legislation of its kind to tackle the issue of Internet Privacy and the collection of individuals data online.GDPR legislated that European citizens should have the right to be informed when they are tracked, to access the data collected about them, to delete their data, and the ability to transfer that data to another platform.

It is Article 7 that obligates companies to seek users affirmative and un-coerced consent before using or collecting a users data that has led to a deluge of websites asking European citizens to accept their cookies. Cookies are targeted in the implementation of GDPR because they are one of the most prevalent methods to track users online. Cookies were initially invented by Lou Montulli in 1996, to solve the problem of websites in-ability to record visitors to their site. They are small text files that are stored on the user’s computer and were originally designed to identify users, save login details, create a customised experience for users and enable websites to remember cart items across multiple web pages. This is still true for first-party cookies. Third Party cookies are cookies which are created by a website other than the one a user is visiting and have the ability to track a user over multiple websites collecting data to sell to advertisers. Third party cookies are the principal concern of privacy advocates due to their surveillance and questionable benefits for the user (Naughton). However, it has been argued by tech companies that this surveillance and tracking is the cost of the free services of these websites. It allows websites to offset the cost of coders, servers, content and all the other costs that go into a website. Websites are financially incentivised to host third-party cookies for advertising which informs their design of consent requests for GDPR.

In their work on the concept of choice architecture the academics, Thaler and Sunstein wrote that ”there is no such thing as neutral design” (page 3). Design, according to the aforementioned academics is informed by the motives of the choice architect. They argued a choice architect can design an environment to encourage users to choose the option of greatest benefit (according to the architect’s metric of benefit). When asking Websites have a financial incentive to encourage and persuade users to accept third-party cookies as the best choice. Websites are obligated to ask consent by GDPR but have a financial incentive to encourage and persuade users to accept third-party cookies as the best choice. The mechanisms of affordance, the use of buttons, fonts and other design elements to demand, refuse, request, encourage, discourage, allow, give a framework into how consent is designed by the choice architects of cookie consent notifications(Davis, and Chouinard, page 244).

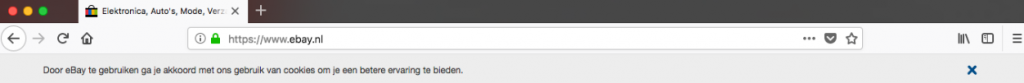

Cookie consent banners like the one used on eBay.com, are often used on popular websites demand acceptance of cookies. They do not intrude on the user’s goal of receiving a service, information or content when visiting the site and need little interaction. It implies the user’s consent to the cookie policy because the user is utilising the website and affords the user no way to opt out. It performs compliance without actively requesting the consent of the user.

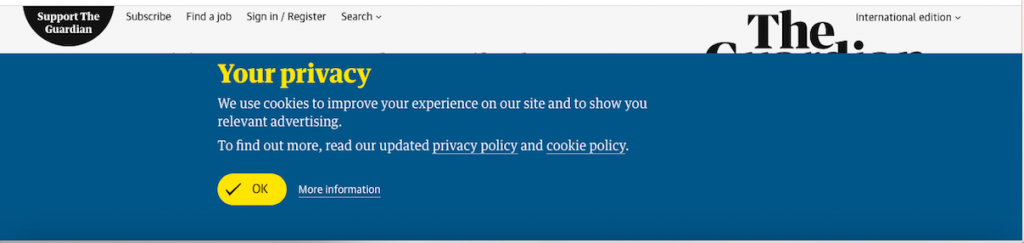

Banners and overlays which display options in small font of ’More Information’ or ’Learn More’, without the option to deny consent are also implying consent. Even if they display a prominent accept button, consent is implied and demanded if there is no other option other then to leave if a user doesn’t consent. The ‘more information’ choice in the cases of Amazon and The Guardian websites, doesn’t offer choice, only information on changing browser settings to reject third-party cookies but no direct link. The design does not allow a user to easily deny cookies, it puts the burden on the user to have dexterity to go through the process of turning off cookies in the browser settings if they wish to deny cookies on a specific website.

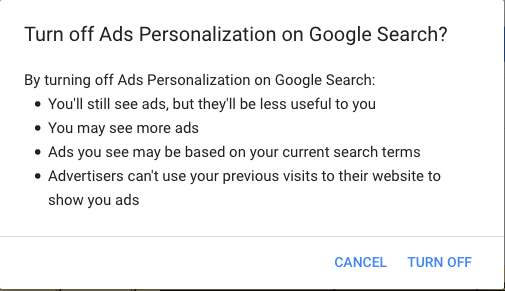

Google and Yahoo encourage users to accept the default privacy measures by having that option as the default and a one-click process. They discourage the tailoring of a users privacy features by increasing the steps required to do so. Google further discourages with pop-ups questioning whether the consumer’s wishes to limit data collection.

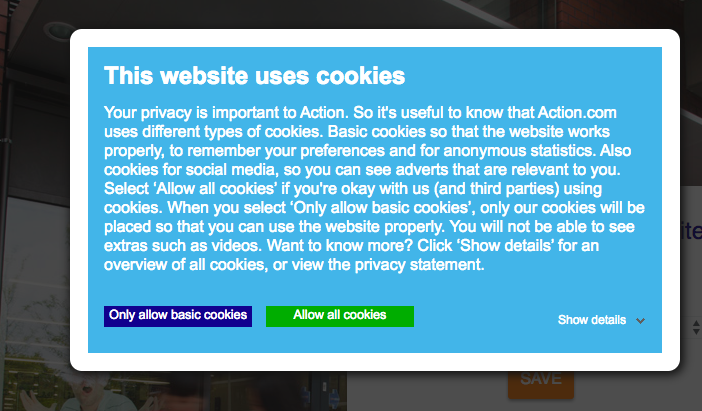

Consent notices give binary options of consent are not exactly common but they are found on Action.Nl. The design encourages users to pick the full cookies because it is green and more central but it still allows users to limiting their cookies.

It is important to talk about these design features of consent requests which have become the standard online because many run contrary to the legislation which they claim to be implementing. GDPR calls for Data protection by design and by default (article 25). This conflict with the current default in consent options which is cookies by default. The default is a powerful thing and the computational design technique of asking persistently consumers to allow all cookies, according to behavioural physiologist Dr B.J. Fogg, is a really powerful way to persuade and wear down consumers (FOGG.page 7) . Accepting the default allows a user access to what they want faster. The button to accept all the cookies compared to the inconvenient and time consuming design of cookie denial incentivises users to allow tracking when they visit a website.

In addition to this the legislation also explicitly states that implied consent is not acceptable. The recital 32 maintains that “Silence, pre-ticked boxes or inactivity should not therefore constitute consent” if there is no active consent from users. The same guideline also states that the request for consent should not be “disruptive to the use of the service for which it is provided”. Such language would indicate that consent requests that prevent a user from accessing the website without consenting to cookies are contrary to the spirit of the legislation. The 42nd recital also states that consent isn’t considered valid unless the user has the ability to withdraw without detriment which means all the boxes europeans have ticked when there was no other option to limit cookies on the content they wanted didn’t count as consent.

GDPR, in theory, is empowering for the individual data subject. It underlines the importance and personal ownership of information in a digital environment that opaquely collects and distributes data as a default. But if GDPR is to be effective it needs to be enforced as the current design of models of consent largely do not comply and re-enforce the status quo of data collection. The privacy non-profit None of Your Business (NYOB) among others have already filed the first complaints against WhatsApp, Facebook, Google and Instagram for instances of ”forced consent” worth billions of euros. The enforcement of this legislation and its definition of consent in court will ultimately influence how seriously companies comply with this regulation in the future but until the verdicts come in we’ll all have to wait and see.

References

Burgess, Matt. “The Tyranny Of GDPR Popups And The Websites Failing To Adapt”. Wired.Co.Uk, 2018, https://www.wired.co.uk/article/gdpr-cookies-eprivacy-regulation-popups. Accessed 23 Sept 2018.

Chen, Brian. “Getting A Flood Of G.D.P.R.-Related Privacy Policy Updates? Read Them”. Nytimes.Com, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/23/technology/personaltech/what-you-should-look-for-europe-data-law.html. Accessed 24 Sept 2018.

Davis, Jenny L., and James B. Chouinard. “Theorizing Affordances: From Request To Refuse”. Bulletin Of Science, Technology & Society, vol 36, no. 4, 2016, pp. 241-248. SAGE Publications, doi:10.1177/0270467617714944.

FOGG., B.J. Persuasive Technology. Elsevier, 2002.

“General Data Protection Regulation.” General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), Intersoft Consulting, gdpr-info.eu/issues/.

Mitchell, Ian D. “Third-Party Tracking Cookies And Data Privacy”. SSRN Electronic Journal, 2012. Elsevier BV, doi:10.2139/ssrn.2058326.

Naughton, John. “We Wanted The Web For Free – But The Price Is Deep Surveillance”. The Guardian, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2014/aug/24/deep-surveillance-is-price-of-a-free-web-advertising. Accessed 23 Sept 2018.

“Noyb.Eu | My Privacy Is None Of Your Business”. Noyb.Eu, 2018, https://noyb.eu/. Accessed 23 Sept 2018.

Sunstein, Cass R. and Richard Thaler . Nudge. Yale University Press, 2008, p. Introduction.

Schwartz, John. “Giving Web A Memory Cost Its Users Privacy”. New York Times, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2001/09/04/business/giving-web-a-memory-cost-its-users-privacy.html. Accessed 23 Sept 2018.