Curing your smartphone addiction: There’s an app for that

Two hours forty-five minutes is the average time per day I spent on my Google Pixel 2 XL smartphone for the past 30 days.

The question here is, do you know exactly how long have you spent on your smartphone each day? Do you really want to know?

Reference: Statista

Reference: Statista

The answer, according to Statista’s Digital Market Outlook research from last year shows that an average American smartphone user spent at least 2 hours 37 minutes per day. Comscore’s Cross-Platform Future in Focus report also shows the average American adult spends 2 hours fifty-one minutes on their smartphone every day.

Why are you addicted to your smartphone?

The most influential technology platforms thrive on the attention economy. Put simply, attention economy is “an approach to the management of information that treats human attention as a scarce commodity, and applies economic theory to solve various information management problems.”

This theory put forward by Matthew Crawford, posits that users are not the customers of platforms. Instead, our attention becomes the product being sold to advertisers partnered with the platform owners. User attention is measured through time spent on site or app. Hence, it is imperative for tech platforms to design their app in such a way that encourage users to stay on as long as possible.

For example, Netflix and Youtube design their video players with builtin ‘autoplay’ after the current video has ended. The autoplay function encourages the user to continue watching despite his original intention. The app can also send notifications to user’s phone screen to notify them when a new episode of their subscribed show has arrived, nudging them to return to the app immediately.

Youtube’s autoplay feature is set as default. Once your current video has finished, the next one suggested through Youtube algorithm to best match your interest will play at once.

Proponents of Facebook and Google argue that tech companies have exploited behavioural principles in interface design to retain users’ attention. Such activity might not necessarily be ethical nor healthy for platform users. A psychology study in 2016 shows that prolonged use of a smartphone is linked with depression.

The design principle behind platforms’ behavioural manipulation is not new. B.J Fogg, a Standford professor pioneered the concept of persuasive technology in the late 1990s. Fogg’s workshops and seminars saw participants who later on became tech companies entrepreneur including the co-founders of Instagram and the Director of Growth at Uber. Both implemented Fogg’s concept in their respective company to great success.

“If you can’t measure it, you can’t improve it.”

Prior to 2018, there were very little tools to help you track time spent on a smartphone. It wasn’t an issue before, not until the “Time Well Spent Movement”, led by Tristan Harris, former Google Design Ethicist brought up the smartphone addiction issue through his essays and talks on large media outlet such as the Huffington Post, TED Talk and De Spiegel.

Harris argues that large media platforms hijack our minds through behavioural manipulation techniques deployed in apps and website’ user interface, such as push notifications and other behavioural nudges. Throughout early 2018, tech companies namely Facebook, Google, and Apple faced much criticism for intentionally design their products to retain user attention for as long as possible. They promptly responded with tools to assist user check time spent on their smart devices and apps.

Introducing Google Digital Wellbeing

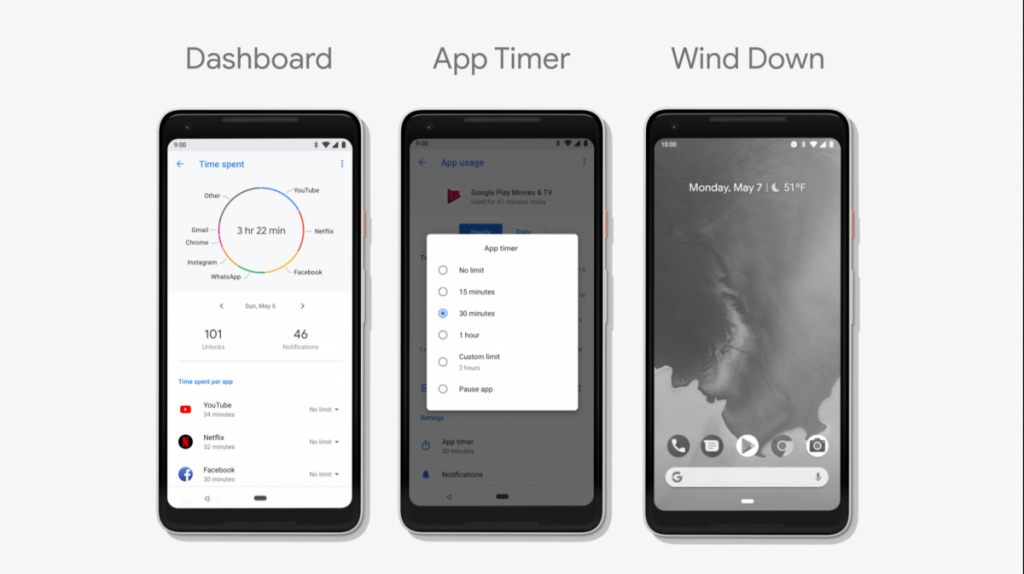

Google was the first to launch its time tracking tool. With its launch of the Android latest operating system in August 2018, Google released “Digital Wellbeing” app designed to help people spend less time on their phones.

The app can be found within Android Pie settings menu, where the user can track how much time they spend using specific apps each day, or how many times they unlock their phones. Once users are aware of the time spent on the phone, the app also provides a toolset to curb the addiction. It allows users to set usage limit on individual apps alongside features that discourage them from checking their phone frequently. Such features include, forced black and white screen mode during night time, blocking notifications.

This information paints an overall picture of your smartphone usage habit. It helps users confronts the reality of smartphone addiction. What you might call ‘just checking my feed for 5 minutes’ could actually be an hour of mindless browsing. I was aghast to see the app quantify my valuable time wasted in trivial activities, much of it on social media.

The right step, but is it a mere gesture?

After using Google Digital Wellbeing tools for a month, it did help me reduce overall time spent on my smartphone significantly. Google did a great job visualising the exact amount of time I spent on the phone and providing enough toolset to discourage unnecessary activity. It works best for users that are aware of their smartphone addiction habit and want an appropriate tool to track and curb time spent on their smartphone. While the app itself is in beta stage, it is clear that a lot of thought went into this app.

Nevertheless, I remain sceptical regarding technology companies’ motivation. These digital wellbeing tools are inherently against the platform’s business model by nature. The fewer time people spend on their smartphones, the less they stay on platforms, the less money platforms make.

The question raised, then, is to what extent tech companies like Google, Apple, and Facebook are serious about reducing smartphone addiction? Are they releasing these apps simply to appease the public and investors against the backdrop of the Time Well Spent Movement? Will they continue developing these tools and increasing their effectiveness in the future? Ben Thompson calls this move ‘Strategy Credit‘ “where doing the right thing is easy because it doesn’t actually hurt the underlying business.”

In closing, through experimentation with Google Digital Wellbeing app, it is clear that we should be more aware of our relationship with personal technology or risk being manipulated. Some tech companies appear eager to respond to public criticism, yet many more remain silent despite extensive use of persuasive technology in their interface design. Tinder and Snapchat, for example, did not respond to this issue at all, despite the fact that their app’s design utilises gamification and behavioural nudges extensively.

Evgeny Morozov put it best: “We do not bring our stable, authentic self to technologies we use, only to recover it in the same mint condition ten years later.”

Bibliography

Armstrong, Martin. ‘Smartphone Addiction Tightens Its Global Grip’, Statista, 2017. https://www.statista.com/chart/9539/smartphone-addiction-tightens-its-global-grip/

Crawford, Matthew B, ‘Introduction, Attention as a Cultural Problem’, The World Beyond Your Head: On Becoming an Individual in an Age of Distraction, 2015, Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 11.

Ellis, Sabrina, ‘Try out Digital Wellbeing to find your own balance with Pixel’, Google, 2018. https://www.blog.google/products/pixel/try-out-digital-wellbeing-find-your-own-balance-pixel/

Fogg B.J. ‘Persuasive Technology: Using Computers to Change What We Think and Do’, Introduction, Stanford University, 2003.

Griffith, Erin. ‘Facebook’s new focus on community might actually depress you’, Wired, 2018. https://www.wired.com/story/facebooks-new-focus-on-community-might-actually-depress-you/

Harris, Tristan. ‘How Technology Hijacks People’s Minds’, Huffington Post, 2016. https://www.huffingtonpost.com/tristan-harris/how-technology-hijacks-peoples-minds_b_10155754.html?guccounter=1

Harris, Tristan. ‘The Slot Machine in Your Pocket’, De Spiegel, 2016. http://www.spiegel.de/international/zeitgeist/smartphone-addiction-is-part-of-the-design-a-1104237.html

Lipsman, Andrew. ‘Mobile Matures as the Cross-Platform Era Emerges’, Comscore, 2017. https://www.comscore.com/Insights/Blog/Mobile-Matures-as-the-Cross-Platform-Era-Emerges

Morozov, Evgeny. ‘To Save Everything, Click Here: The Folly of Technological Solutionism’, PublicAffairs, 2013. p. 233.

Panova, T & Lleras, A 2016, ‘Avoidance or boredom: Negative mental health outcomes associated with use of Information and Communication Technologies depend on users’ motivations’, Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 58, pp. 249-258. DOI: 10.1016/j.chb.2015.12.062

Stolzoff, Simone. ‘The Formula for Phone Addiction Might Double As a Cure’, Wired, 2018. https://www.wired.com/story/phone-addiction-formula/

Thaler, Richard H. & Sunstein, Cass R. ‘Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness’, Yale University Press, 2008. 1-14.

Thompson, Ben. ‘Facebook’s Motivations‘, Stratechery, 2018. https://stratechery.com/2018/facebooks-motivations/