Matteo Salvini and the potentials of Facebook live-stream

Politicians are among the most affected by the breaking of live-stream services in social networks: this new communication has opened up uncharted ways to interact with supporters. Matteo Salvini, the most influential representative of European far-right populism, has developed one of the most effective social media communication strategies turning this feature in the key for his success.

Politicians are among the most affected by the breaking of live-stream services in social networks: this new communication has opened up uncharted ways to interact with supporters. Matteo Salvini, the most influential representative of European far-right populism, has developed one of the most effective social media communication strategies turning this feature in the key for his success.

The rise of populism in the Western world has often been linked to social networks, considered to be favourable environments for its proliferation exploiting a subsoil made of fake-news, oversimplification of reality and memes. I don’t want to suggest that the digital arena is inherently the root of all current evil. I will try instead to argue that the ability demonstrated by populist political communication is related to a coalescence of network inherent features, visual strategies and innovative approaches that lead to such efficacy.

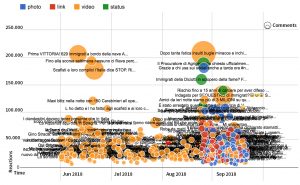

I conducted a limited quantitative analysis based on the Salvini’s account activities in the 16 weeks following his official assignment to the Home Office. As shown in the bubble chart Salvini’s posts are consisting almost entirely of videos and live-streams; even when photo, link or status are posted, videos still remain the most vivid contents collecting more likes and comments.

Populism and ‘likeability’

What does exactly “populism” mean? It is a nebulous term identifying a thin ideology which operates on the opposition between “the good people” and “the bad elite” (Ernst et al., 2017) demanding the unconditional soveregnity of the people (Wirth et al., 2016). Fabricating a strong category of identification, populist discourse requires an outside to delineate the inside, such as “the elites” and “the others”: the latter is likely to refer to groups such as immigrants, homosexuals, welfare recipients, Roma communities or any other category considered not to be part of “the people” (Bobba, 2017). Giuliano Bobba has conducted a research on Salvini’s party — Lega Nord’s (Northern League) — communication on Facebook. It resulted that a post, in order to achieve a wider communicative efficacy, should employ a combination of two criteria: it should be posted by the leader and it should contain an emotionalised message. A content to be emotionalised has to usually be situated in an either anger or fear framework. Furthermore the posts containing references to “the others”, as opposed to the one against “the elites”, received more likes than the rest.

It is impressive to think how Salvini’s official page had less than 50.000 likes in December 2013, escalated to 1.840.000 likes in June 2017 to the current 3.100.000 likes in September 2018. This was achieved through non-canonical approaches such as the contest “Win Salvini”: each day the fastest person to like Salvini’s posts would have win a call or a meeting with the politician.

The live-stream format: images and discourse

Facebook live-stream gives the opportunity to boost emotionalised contents through its audiovisual form: mainly the long take form, the use of hand camera and the staging expedients.

The long take is usually used in cinema to decrease the perception of the camera mediation. This technique combined with the use of a mobile camera held in Salvini’s hand, amplifies the illusion of a direct participation as if the politician personally addresses the viewer.

At the same time the use of the hand camera allows a strong presence of the politician’s body, that symbolically serves the populist rhetoric, as it is based upon the idea of a leader defending the shared values of the people.

Numerous are the staging expedients employed in the communication, always conveying the idea of informality. The settings for example can be the familiar ones (at home, at the beach or in the mountains with the family) or showing the “backstage” of the political life. The setting is always matched with a casual clothing remarking its political “transparency”. All together these devices aim to communicate the sincerity of the politician and its belonging to “the people”.

Two examples of how Salvini shows his body as a man from the people

Moreover what is said by the leader during a live-stream is often not considered as an official statement, as mainly perceived as “temporary interstitial events” that provide the opportunity to users to temporarily defer their tasks (Chen & Lin, 2018). Although the political relevance of social media communication — as its increasing presence in news media reports reflects — the naturalisation of the political discourse, together with the symbolic strategies analysed, allows Salvini’s rhetoric to address highly-mediated messages with a potential way out of the consequences. This capacity of the live-stream has led to an innovative and chameleonic communication approach: the political discourse can be pushed at the boundaries of the common sense, understanding but concurrently shaping its limits through the users’ direct feedback enabled by live-stream.

Conclusions

The increasing relevance of live-stream contents in social networks, also due to the algorithmic prioritization of these contents while they are live, demand to recognise their weight in the current political representation and to be addressed critically.

As the agency of this new modes of content production is already affecting the common categories of the political discourse, a media-centred methodology of analysis towards these recent, as relevant, shifts in our relation toward the political representation is needed as it shows how politics’ accountability progressively rely upon the aesthetic sphere and unofficial portrayals, receding the traditional communication channels.

References

Bobba, Giuliano. “Social media populism: Features and ‘likeability’ of Lega Nord communication on Facebook.” European Political Science, 2018, pp. 1-13.

Bracciale, Roberta and Cristopher Cepernich. “Hybrid 2018 campaigning: Italian political leaders and parties social media habits.” Italian Political Science, 13.1, 2018, pp. 1-15.

Brookie, Graham and Anna Pellegatta. “#ElectionWatch: Salvini’s Likes Contest. How Matteo Salvini is generating populism with online competition.” medium.com, https://medium.com/dfrlab/electionwatch-salvinis-likes-contest-d029a6312ad6. Accessed 24th Sept. 2018.

Chen, Chia-Chen and Yi-Chen Lin. “What drives live-stream usage intention? The perspectives of flow, entertainment, social interaction, and endorsement.” Telematics and Informatics, 35.1, 2018, pp. 293-303.

Ernst, Nicole, Sven Engesser, Florin Büchel, Sina Blassnig and Frank Esser. “Extreme parties and populism: an analysis of Facebook and Twitter across six countries.” Information, Communication & Society, 20.9, 2017, pp. 1347-1364.

Mudde, Cas. “Fighting the system? Populist radical right parties and party system change.” Party Politics, 20.2, 2014, pp. 217-226.

Oremus, Will. “Facebook Is Becoming Less Like a Newspaper… and More Like Cable News.” Slate, 1st March 2016, http://www.slate.com/blogs/future_tense/2016/03/01/facebook_tweaks_news_feed_algorithm_to_prioritize_live_video.html. Accessed 24th Sept. 2018.

Wirth, Werner, Frank Esser, Martin Wettstein, Sven Engesser, Dominique Wirz, Anne Schulz, and Philipp Müller. “Political populism.” The appeal of populist ideas, strategies and styles: A theoretical model and research design for analyzing populist political communication, NCCR Working Paper 88, Zurich, 2016, pp. 7-18.