The Ultimate ‘Data Selfie’: An era of self-tracking explosion

‘The End of Forgetting’: Self-tracking and the Quantified Self

The Beginner’s Guide to Quantified Self (Image Source: technori.com – courtesy to dotcomplicated.co)

Humans are forgetful. We make errors. We easily neglect matters that are trivial. However, this is not a problem in the 21st century: we have self-tracking apps and devices to take care of them with maximum efficiency. There is a sense of liberation in the idea that you no longer have to ‘remember’ or keep track of every small detail of your everyday life.

In other words, it is ‘the end of forgetting’; software has become optimized to carry out such functions in the digital era which thus “can be understood as the cultural absorption of a general technique for representing data and processes in a manner that can be stored, retrieved and reproduced” (Bossewitch and Sinnreich, 2012). We have reached an era of self-tracking explosion where the self is constantly defined by numbers, through quantified personal data: We have become the ‘Quantified Self’ – a term first introduced by Gary Wolf in Wired magazine as he outlined a detailed description of the numbers he collected through his daily activities (2009). In fact, on the following article he published on the New York Times in 2010, he specifies this concept with a greater insight:

When we quantify ourselves, there isn’t the imperative to see through our daily existence into a truth buried at a deeper level. Instead, the self of our most trivial thoughts and actions, the self that, without technical help, we might barely notice or recall, is understood as the self we ought to get to know. Behind the allure of the quantified self is a guess that many of our problems come from simply lacking the instruments to understand who we are.

(Wolf, 2010)

You do not simply become part of your data; “[y]ou are your data” (McClusky, cited in Lupton, 2016) since self-tracking can be understood as a private enterprise where an intense focus lies on the self in which it becomes a part of the ‘new individualism’ that conform both to the notion of self-work and self-improvement (Lupton, 2015).

And guess what? You can now turn your data (a.k.a. yourself) into a beautiful form of art.

Laurie Frick and the ultimate ‘data selfie’: From ‘Floating Data’ to FRICKbits

‘Floating Data’ 1, Laurie Frick. 2014-15.

Laurie Frick is a data artist who uses self-tracking data on personality, mood, exercise, sleeping patterns, etc. to create delicate handcrafted objects and large-scale installations with basic materials such as wood, dyes, glass, and laminate. Her hands-on experience in tech industry for more than 20 years has led her to the artistic exploration of the future of the quantified self, where self-tracking devices could gather and present patterns of how we feel, stress level, mood and bio-function digitally recorded and physically produced as intelligent wallpaper (Thoma, 2014). Frick openly claims on her website that these “offer a glimpse into a future of data about you […] [which] will look a lot like hand-built art sourced from a digital algorithm that spits out room-sized pattern” (Accessed 23 Sep 2018).

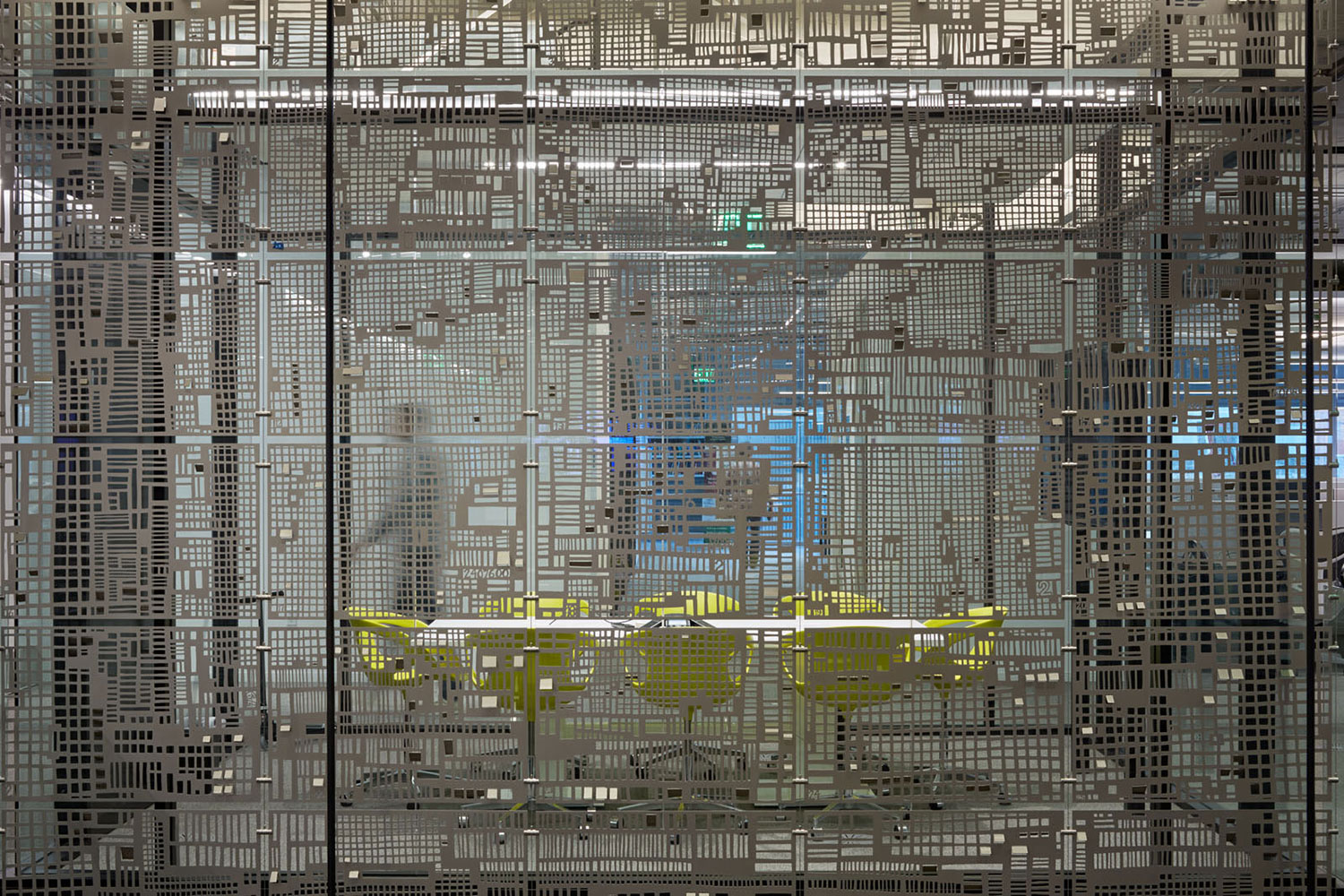

‘Floating Data’ 2, Laurie Frick. 2014-15.

One of her recent works known as ‘Floating Data’ is a two-stories tall installation, made from 60 anodized aluminum panels which represent her walking patterns gathered on her Fitbit and combining it with location data from the online program OpenPaths and her iPhone’s GPS (Urist, 2015). Her work focuses on the concept of location and tracking where she believes that they reflect human routines of life. Frick asserts that “self-tracking data is like a pattern portrait of you”; she further states that “we recognize those portraits, finding something human in the data patterns, though we don’t know why it feels familiar” (Pangburn, 2014). She refers to her art as ‘data selfies’, where they present abstract self-portraits that reveal volumes about their subjects with her clear outlook of an optimistic, cheerful future of data (Patterson, 2015). This belief enabled her project to expand by generating participation from the general public, through the launch of her app called FRICKbits which turns personal location data into patterns of your own custom ‘data selfie’.

“Take back your data and turn it into art”: Reclaiming your own data?

As a self-proclaimed data activist, Frick also comprehends that such type of data collection can cause discomfort as it lies on the tangent of surveillance and privacy issues. Yet, she assertively remarks that “‘Take back your data’ is more about ownership than privacy”:

“I’m not saying your data doesn’t need to be private,” Frick says. “But I’m saying that data collected about you is inevitable. How can that data come back to me in a way that actually makes something good for me?”

(cited in Patterson, 2015)

She underlines the idea of ‘user data empowerment’ where through the process of turning personal data into personal art, it allows you to reclaim your own data. You, as a user, gain the power of agency regardless of who is tracking your data – whether that is Google or the government – since you have now turned it into something that is ‘meaningful’; something that gives you “a sense of mindfulness” (Frick, cited in Patterson, 2015).

However, it is still hard to neglect the questions arising upon the power dynamics on the collected personal data and the configuration of the self:

Aside from the obvious concerns this development poses regarding privacy and exploitation, it also raises the specter of a deeper, ontological crisis. Historically, members of our society have taken for granted that we know more about our lives than any third party possibly could, and this knowledge has been vital to our sense of ourselves. The fact that digital databases can now tell volumes more about us than we know about ourselves suggests that the very process of identity-construction is in distress.

(Yesil, cited in Bossewitch and Sinnreich, 2012)

Frick “sees her role as convincing people to want more personal data” as she views this as a solution for issues upon data privacy which would lead to gaining further sense of ownership (Pangburn, 2014). While this provides us with a very optimistic outlook of the future of data, it also insinuates a highly risky encouragement of the constant and possibly full exposure of one’s personal data. Could we say that this ultimately gives us a true agency of the self – while we are not only giving our personal data to the marketers, the government, and all other unknown power models through the use of self-tracking devices, but also by publicising our private data as an artwork?

Thus, “will the ever-growing mass of personal data ever achieve the dimension of nuance required, to profoundly help us revise or re-contextualize our sense of self”? (Artist Laurie Frick: Making Much of the Immaterial and Big Data, 2018)

Works cited

“Anticipating the Future of Data about You.” LAURIE FRICK, www.lauriefrick.com/.

“Artist Laurie Frick: Making Much of the Immaterial and Big Data -.” The Privacy Guru, 2 Mar. 2018, www.theprivacyguru.com/blog/artist-laurie-frick-making-much-immaterial-big-data/.

Bossewitch, Jonah, and Aram Sinnreich. “The End of Forgetting: Strategic Agency beyond the Panopticon.” New Media & Society, vol. 15, no. 2, 2012, pp. 224–242., doi:10.1177/1461444812451565.

“Laurie Frick | Data Artist | CreativeMornings/ATX.” CreativeMornings, creativemornings.com/talks/laurie-frick/1.

Lupton, Deborah. “Self-Tracking Cultures: towards a Sociology of Personal Informatics .” Proceedings of the 26th Australian Computer-Human Interaction Conference on Designing Futures the Future of Design – OzCHI 14, 2014, doi:10.1145/2686612.2686623.

Lupton, Deborah. The Quantified Self: a Sociology of Self-Tracking. Polity, 2016.

Lupton, Deborah. “You Are Your Data: Self-Tracking Practices and Concepts of Data.” Lifelogging: Theoretical Approaches and Case Studies about Self-Tracking , 2016, pp. 61–79., doi:10.1007/978-3-658-13137-1_4.

Pangburn, DJ. “This Is What a ‘Data Selfie’ Looks Like.” Motherboard, VICE, 12 Aug. 2014, motherboard.vice.com/en_us/article/d73y9y/frickbits-turns-personal-data-into-works-of-art.

Patterson, Lindsey. “Artist Laurie Flick Takes Data on Her Daily Life and Transforms It into Art.” Public Radio International, www.pri.org/stories/2015-07-08/artist-laurie-flick-takes-data-her-daily-life-and-transforms-it-art.

Sydell, Laura. “An Artist Sees Data So Powerful It Can Help Us Pick Better Friends.” NPR, NPR, 25 Feb. 2018, www.npr.org/sections/alltechconsidered/2018/02/25/583682718/an-artist-sees-data-so-powerful-it-can-help-us-pick-better-friends?t=1537652990505.

Urist, Jacoba. “How Data Became a New Medium for Artists.” The Atlantic, Atlantic Media Company, 15 May 2015, www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2015/05/the-rise-of-the-data-artist/392399/.

Wolf, Gary. “The Data-Driven Life.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 28 Apr. 2010, www.nytimes.com/2010/05/02/magazine/02self-measurement-t.html.

Yeslie, B. “Blind Spots: the Social and Cultural Dimensions of Video Surveillance.” 2005.