There is Power in a Union!

Earlier this year, riders for food delivery services UberEats and Deliveroo went on strike, contesting the companies’ decision to move from contracts to subcontracting their employees (Van Unen). This would exempt the companies from paying taxes over their employees’ wages and strip the workers of the benefits of being employed, such as paid leave and compensation for illness. This may sound familiar for many workers in app-based jobs, the media industry or in software development. They are part of what Guy Standing calls the precariat:

In terms of characteristics, most in the precariat live through a series of casual, short-term, or temporary jobs, have none of the forms of labor security that the working class and the salariat acquired in the welfare-state era, and have relatively low and insecure earnings. (Standing 590)

They are mostly young workers, competing over jobs in highly individualized fields. Due to the short lived nature of their contracts, they often form loose bonds with their co-workers. They might not be there next month, so building a strong relation is not possible. This quick rotation of workers also results in a lack of identification with their craft. The short length of contracts also discourages workers from speaking up about working conditions and injustices. When workers do get organised, it is often difficult to keep them organized due to people finding new work or having their contracts terminated.

Examples of these issues can be seen through protests in various places in the world. The struggle between food delivery workers and the companies they work for has been ongoing for multiple years, with earlier strikes in Paris, Turin and China. The outcomes of these strikes have been mixed. The strikers in Turin did not have their demands met, but their demands formed the basis for law proposals put forth by the left-wing party Sinistra Italiana (Tassinari and Maccarrone 355). Eventually, most workers moved on to other jobs, leaving the rest powerless. The companies wait out the unrest and continue business as usual. That is where Wobbly comes in.

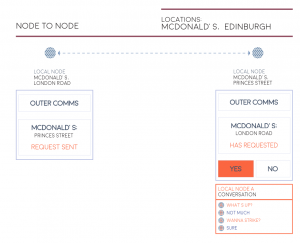

Wobbly aims to provide workers with tools to organize their workplace. As the name suggests, this app is based on the organisational structure of the International Workers of the World. Workers form small groups in their workplace and become a node. In this node they can plan meetings and actions, pool funds and communicate privately. This effectively enables workers to start their own union with the app (DeMaria 3) whilst introducing them to proven methods of organizing.

It is furthermore interesting to note that the app is not limited to small local groups, but instead aims to connect the smaller nodes into super nodes. When the workers of McDonald’s Damrak and McDonald’s Leidseplein both want to start a strike, this super node can help them plan a larger scale action without the need to form a bigger group. Instead, the nodes choose spokespeople who communicate with each other to organize the strike. This gives great power to the workers, as it allows them plan large scale actions, without creating unmanageable large group chats.

One of the most important features of Wobbly is the ability to communicate ‘outside the view of the employer’ (3). Like most other people, activists use chat apps to stay in contact with each other. Knowing who is in a group is easy when there are ten people in that group. But when workers are organizing a city-wide strike and the number of participants rises over a hundred people, managing a group becomes impossible. Wobbly tries to eliminate employer interference by using small groups as a foundation. The importance of private communication is exemplified by Foodora, as they are known to get rid of the ‘troublemakers’ in the company (Vandaele 15). They will remove all the hours that an employee is scheduled to work or revoke access to the platform, thereby rendering this employee unable to work.

It is furthermore important to note that Wobbly is fully open-source and currently maintained by an ex-Foodora employee. Traditional unions are slow to adapt to changing labour conditions (Animento et al 272). Apps on the other hand can change very fast, especially when there are multiple people working on a project. The open stance the developer has on feedback, including an open Github and his personal contact information, also invites users to work and expand upon the already existing code and input their ideas for new features. It would also benefit traditional unions to pay attention to the development of this application and incorporate similar software into their strategies. With the emergence and rapid growth of job-apps and the steady decline of union membership, it would be unwise for them to not seek new methods of organizing workers.

Organizing workers and going on strike is as relevant today as it was in the past. The new class of the precariat is burdened with increasing workloads without fair compensation. Meanwhile, employers such as Foodora and Deliveroo claim little to no responsibility for the well being of their employees and their working environment. Existing unions have proved unable to effectively organize the workers and better their working conditions. Most protests that Workers in precarious situations need the tools to organize themselves outside the existing union structures, in both the physical and digital world. The developers of Wobbly have set out to create a platform where workers can do just that. Enabling workers to organize themselves gives them greater control over their actions and goals, can give them a sense of pride in their work and instill camaraderie between workers.

Literature

Animento, Stefania, et al. “Total Eclipse of Work?” PROKLA. Zeitschrift Für Kritische Sozialwissenschaft, vol. 47, no. 187, 2017, pp. 271–290.

DeMaria, Alfred T. “The Future of Internet Organizing.” Management Report for Nonunion Organizations, vol. 39, no. 2, 18 Jan. 2016, pp. 3–4.

Standing, Guy. “The Precariat: From Denizens to Citizens?” Northeastern Political Science Association, vol. 44, no. 4, Oct. 2012, pp. 588–608.

Tassinari, Arianna, and Vincenzo Maccarrone. “The Mobilisation of Gig Economy Couriers in Italy.” European Review of Labour and Research, vol. 23, no. 3, 10 Aug. 2017, pp. 353–357.

Vandaele, Kurt. “Will Trade Unions Survive in the Platform Economy? Emerging Patterns of Platform Workers Collective Voice and Representation in Europe.” SSRN Electronic Journal, 2018.

Van Unen, David. “Opnieuw Staking Bezorgers Deliveroo.” Het Parool, 11 Jan. 2018.

“Techno-Syndicalism.” Bananananaba, bananananaba.com/Techno-Syndicalism-Outline.html.

Techno-syndicalism, Wobbly-App, (2018), GitHub repository, https://github.com/Wobbly-App/techno-syndicalism