Vote yay or vote nay, but you just can’t ignore micro-targeting.

Figure 1: Phillip Flotz paints Athenian democracy leader Pericles addressing the assembly. Source: Wikipedia

“Numbers and democracy have always been linked.”John Durham Peters proclaims, giving examples from Greek political systems to modern opinion surveys. He focuses on majority – the social force through numbers, that democracy uses to establish legitimacy (434). And when we zoom in to the majority today, we find micro-targeting.

An introduction to micro-targeting: Chasing a majority with the ‘micro’

Political micro-targeting, is a practice that has recently grabbed the interest of marketers, academics and watch-dogs alike. For this, we can partly give credit to the Cambridge Analytica scandal without which the word may never have come focus outside of scholarly work on political communication and data-mining.

Bodó et al. give a comprehensive definition, writing that political micro-targeting (micro-targeting for the purpose of this piece) refers to the use of different communication (both online and offline) to communicate and build a relationship with prospective votes. They go on to call out the heart of the concept as it is today- “the use of data and analytics to craft and convey a tailored message to a subgroup or individual members of the electorate” (3).

Figure 2: Bloomberg Businessweek covers the use of micro-targeting by the far right in Germany which saw them make impressive gains during the last elections. Source: Bloomberg Businessweek

Two aspects of this definition stand out. Firstly, it’s not ‘new’. Targeting and segmentation of voters has always been part of political campaigning, in fact Bodó et al. add – there is a long history of segmenting the ‘voter market’ to optimise campaign messages to different profiles. A somewhat extreme example of this is in post-partition India where different religious groups or castes have been given different messages by the same campaigner- ones that can even be at odds at with each other.

However, while it may not be new conceptually, but micro-targeting is new in almost every form of its planning and execution, giving it new potency. First, in the identification and profiling of the audience- the ‘richness’ and detailing of data available is immense and has almost no resemblance to the more rudimentary voter-data of the past. Here, data is collected and analysed from the widest range of online and offline sources and comprehensive psychographic, behavioural, attitudinal profiles developed (qtd in Chester and Montgomery 4). The article also brings up ‘data brokers’ the intermediaries who handle and analyse this data.

These audience segments are identified and classified, now with an almost surgical precision. Following which, the scale at which customised communication can be meted out, is almost unimaginable. Brad Parscale, who ran Donald Trump’s digital campaign and tells Julia Wong, he typically used 50000-60000 variations of Facebook ads each day. This scale is unprecedented and could not have been imagined previously, that too in any kind of cost effective manner. This also highlights that it is entirely possible for only the desired set to see this commercial/ message, and for other sets to see an entirely different message , even if it’s on the same issue. Whereas on mass media – even if there was some geographic and channel-audience based targeting- it was largely out of control of the advertiser who else could watch it once it was on air.

The rise of micro-targeting: Emerging, influential and extremely controversial

It’s widely accepted that it is the United States presidential elections over the last decade that initiated and brought to light this practice (Krushchinski and Holler 2) . While there is arguably nothing ‘bigger’ than that political stage and scale, micro-targeting can still be seen as an emergent practice. The first measure of this is watching it widen its reach – spreading geographically, in European elections and referendums through political and technical consultants (Bennett 261), and similarly to India, Argentina, Mexico and Chile etc. (“The Influence Industry” Series). It’s logical to assume that this increased reach also means the trickling down of these practices to smaller political and ideological campaigns.

The second reason why this practice is still emergent rather than established is that it is dramatically evolving with changes in technology, for example the cross-device targeting that wasn’t possible a few years ago (qtd in Chester and Montgomery). We are still to see the possibilities of such technologies and their use. In fact, ex-Microsoft executive Cyrus Krohn adds a new word to the mix, ‘nano-targeting’, (qtd in “It might work too well’: the dark art of political advertising online”). You know how the sign of a great communicator is how he/she makes it seem like they’re only talking to you? Well, with micro, to nano-targeting, we’re almost there.

Micro-targeting under the microscope: understanding the issues around the practice

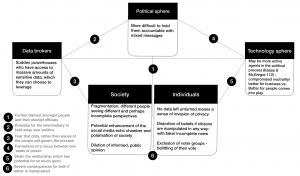

Perhaps because it’s as aspect of the democratic process that almost from the time revelations of this practice came out especially with the rise of the all important data management , there have been some red flags from journalists and academics alike. Some of the core issues have been shown below:

Figure 3: Covers the concerns and controversies surround micro targeting, compiling and building on some of the key writings that have critiqued the practice, including Bennett; Bodo et al.; Borgesius et al., Chester & Montgomery and Kreiss & McGregor.

The Indian perspective: Micro-targeting in billions?

The world’s largest democracy (1.3 billion people) goes to the polls in 2019. This will be the second election for Prime Minister Modi who was elected with a comprehensive majority, attributed to his media strategy, particularly his use of social media . If social media was the buzzword for the last election, it has now moved to micro-targeting (Sharma) and data-driven campaigning.

Hickok (11) however, highlights that in India large sets of data have not yet been standardized, cleaned or at times not even digitized. While the above is a challenge for advertisers, the challenge for users and the country as a whole is that education about paid political advertising, concepts like micro-targeting or even of personal data safety is inadequate. And though initiated, the formalising of data protection regulation is a while away. There is, therefore, a genuine concern for the misuse of data and the threat of political manipulation.

Concluding thoughts: Read, research and regulate

This blog begins by exploring the recent hype surrounding micro-targeting, however we quickly realise that most scholars agree it is a conceptually well-established concept, now with different and much more complex execution.

As we look at the rising potency and spreading reach of micro-targeting, we realise, current research and rhetoric continues to be US-centric, along with some European focused study in the last year. Far more attention needs to be paid to practices, unique challenges and key stakeholders (e.g. data brokers), in different countries and contexts. For examples it’s important to note the important role of apps like Whatsapp in the targeting process in markets like Brazil (Moura and Michelson) and India (Sharma).

The key reason we need to study this amidst the different contexts, is simple- it’s the need for regulation. And one can argue, the specific need of the hour is regulation that takes into account a deep understanding of regional, cultural and demographic nuances when it comes to personal data and democracy. The EU’s General Data Protection Regulation and America’s Honest Ads Act, that calls for greater regulations in the content of and spending for technology-intensive campaigning (Kreiss qtd in Chester and Montgomery), could potentially be on the right track, but bringing them to other contexts without robust independent research would not be an answer. Micro it may be, but it will take a substantial commitment to keep this practice from being abused and the irony is, to ensure this, we need to collect some more data.

REFERENCE LIST

Bennett, Colin J. “Voter databases, micro-targeting, and data protection law: can political parties campaign in Europe as they do in North America?”. International Data Privacy Law 6. 4 (2016): 216-275. 18 September 2018. <https://academic.oup.com/idpl/article-abstract/6/4/261/2567747>

Bodó, Balazs., Helberger, Natali, and de Vreese, Claes H. “Political micro-targeting: a Manchurian candidate or just a dark horse?”. Internet Policy Review 6. 4 (2017). 13 September 2018. DOI: 10.14763/2017.4.776

Borgesius, Frederik J. Zuiderveen et al. “Online Political Microtargeting: Promises and Threats for Democracy”. Utrechrt Law Review 14. 1 (2018). <doi.org/10.18352/ulr.420>

Chester, Jeff, and Montgomery, Kathryn C. “The role of digital marketing in political campaigns”. Internet Policy Review 6. 4 (2017). 14 September 2018. <http://policyreview.info/articles/analysis/role-digital-marketing-political-campaigns>

Hickok, Elonnai. “The Influence Industry. Digital Platforms, Technologies, and Data in the General Elections in India”. Tactical Technology Collective.(2018). 18 September 2018. <ourdataourselves.tacticaltech.org/media/ttc-influence-industry-india.pdf>

“The Influence Industry Series” (Overview). Tactical Technology Collective.(2018). 22 September 2018. <ourdataourselves.tacticaltech.org/posts/overview-india/>

Kreiss, Daniel and McGregor, Shannon C. “Technology Firms Shape Political Communication: The Work of Microsoft, Facebook, Twitter, and Google With Campaigns During the 2016 U.S. Presidential Cycle”. Political Communication 35. 2 (2018): 155-177. 18 September 2018. <doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2017.1364814>

Kruschinski, Simon, and Haller, Andre. “Restrictions on data-driven political micro-targeting in Germany”. Internet Policy Review 6. 4 (2017). 13 September 2018. <policyreview.info/articles/analysis/restrictions-data-driven-political-micro-targeting-germany>.

Moura, Mauricio, and Michelson, Melissa R. “WhatsApp in Brazil: mobilising voters through door-to- door and personal messages”. Internet Policy Review 6. 4 (2017). 13 September 2018. DOI: 10.14763/2017.4.775

Peters, John Durham. “The Only Proper Scale of Representation”: The Politics of Statistics and Stories. Political Communication 18. 4 (2001): 433-449. DOI: 10.1080/10584600152647137.

Sharma, Nidhi. “Micro voter targeting is all set to enter India with 2019 Lok Sabha polls”. The Economist. (2018). 20 September 2018. <https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/micro-voter-targeting-is-all-set-to-enter-india-with-2019-ls-polls/articleshow/60947195.cms>.

Silver, Vernon. “The German far Right Finds Friends Through Facebook”. Bloomberg Businessweek. (2017). 18 September 2018. <bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-09-29/the-german-far-right-finds-friends-through-facebook>

Wong, Julia Carrie. “’It might work too well’: the dark art of political advertising online”. The Guardian. (2018). 21 September 2018. <https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2018/mar/19/facebook-political-ads-social-media-history-online-democracy>.