Trigger Block: A plug-in making online life easier for people living with mental illness

18.5% of Americans experience mental illness in a given year (National Institute of Mental Health). With this percentage increasing throughout the years, one can wonder if the online world could bring comfort for those suffering with mental illness. To make the online world a safer place for those encountering trigger issues, we came up with an idea. Our goal is to to develop a median ‘product’ that would be able to help its user. We were concerned that many users of social media sites are being triggered by certain words that they are exposed to. The context in which these words may appear could have a crucial impact on mental health.

Understanding Post Traumatic Stress Disorder and triggers

Post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a long lasting mental health issue, that some people develop after “experiencing or witnessing a life-threatening event, like combat, a natural disaster, a car accident, or sexual assault” (US National Centre for PTSD). It was originally thought, that it was the reverberations of war on certain veterans. However, the mental health condition can affect anyone through all age groups, even children under the age of one (The Refuge). About 50% of women and 60% of men overall will experience at least one traumatic event in their lifetime (National centre for PTSD) and from there about 8% of men and 20% of women will develop PTSD.

People with PTSD may feel stressed or even scared when they are not in danger, as the brain does not process the traumatic event in the correct way (WebMD). Instead of placing the memory in the past, the brain re-lives it and the body reacts with stress and fear. Furthermore, the symptoms also include having prolonged night terrors or flashbacks of the event, feelings of detachment to everyday life, getting easily irritated or having violent outbursts. Someone who suffers from PTSD also tries to avoid certain places, people or events that can trigger a memory. PTSD symptoms can come and go over time. However, there are certain triggers which can set off these symptoms and bring back the traumatic event. These triggers are pressure buttons, and when they are pushed the body goes into fight or flight mode, developing the feeling of fear and heightened heart beating (WebMD). Examples of triggers could be smells, sounds or words that brings back traumatic memories. Some triggers are more visible than others, especially in today’s society, where we are easily exposed to news, images, sounds via our virtual world. This rose the question about context exposure, and certain vocabulary affecting its users. From this we proposed the research question: “Can we use preventative measures to avoid triggering people’s mental health issues?”

We specifically decided to put emphasis on PTSD for this project, as it affects numerous people across the world and something so innocent as a word could trigger highly emotional reactions in the internet user. The plug-in, named Trigger Block will focus on helping people with mental health issues by muting sensitive words on web browsers. We believe that this will help decrease the trigger symptoms for potential users, as they can lessen the risks of flashbacks that are associated with the words.

Algorithms, hate speech and privacy

With our browser plug-in, we want to give the power back to users in terms of what content they choose to consume online. Instead of a controlling power regulating the content one can view, one will have the ability to self-regulate. By allowing users to choose what words that they want to omit from their newsfeed or online searches, they are empowered to take back some control that they surrendered when signing up for particular social media platforms. Lippold is concerned that “we are losing ownership over the meaning of the categories that constitute our identities” (Lippold 178). In this way, we provide a tool that can fight back against the force of algorithms that tells us “who we are, what we want, and who we should be” (Lippold 177).

We are at the mercy of the algorithms of various social media platforms as to what we are shown on our timelines. In order to tailor our individual experiences online, platforms use algorithms to collect data about our likes and preferences. They then use this information to feed back to us what they think is most relevant and target advertisements at us that we will be most susceptible to. Our click-behaviour on different platforms is nudged in particular directions that favour the choice architect; for example Google aims to promote use of Google apps by driving web traffic in certain directions (Yeung 121). Often platforms do not always have our best interests at heart while creating our individual online experience. Facebook was criticised in the past for an emotionally manipulative experiment that it carried out on users’ News Feeds, but defended themselves by stating they were trying to improve their algorithms and make user content more relevant (Yeung 123). Outside of the fact that algorithms can intentionally alter our emotions, they can limit our identities, and ultimately decide who our online selves are. “‘Users’ identities need to be defined within a fixed set of standards in order to be compatible with the algorithmic logic on which these software systems run” (Bucher 482).

Many social media platforms have come under fire as of late for their slow-responses in taking down instances of hate speech from their sites. Furthermore, “A recent European survey showed that 75% of those following or participating in debates online had come across episodes of abuse, threat or hate speech” (European Commission). Evidently, social media platforms are rife with instances where people are made to feel uncomfortable, attacked or unsafe. For those who suffer from mental health problems, this can be particularly damaging. Therefore, the ability to create your own safe space online can be an important power to have.

As our plug-in must be allowed access to various social media sites in order to view the content and block that which may be triggering for the user, it raises issues of data privacy. Is it safe to give a browser plug-in access to all of this personal information in the hopes of it being beneficial for your mental health? Trigger Block aims to store no personal data of the user to be used for targeted advertisements and has no monetary aims. Similarly, “a user should be able also to temporarily disable a monitoring product without fully uninstalling it” (Martin et al 46) which we aim to do by giving the option of un-muting words which previously were chosen trigger words for the user.

Hashtags and content moderation: a complex connection

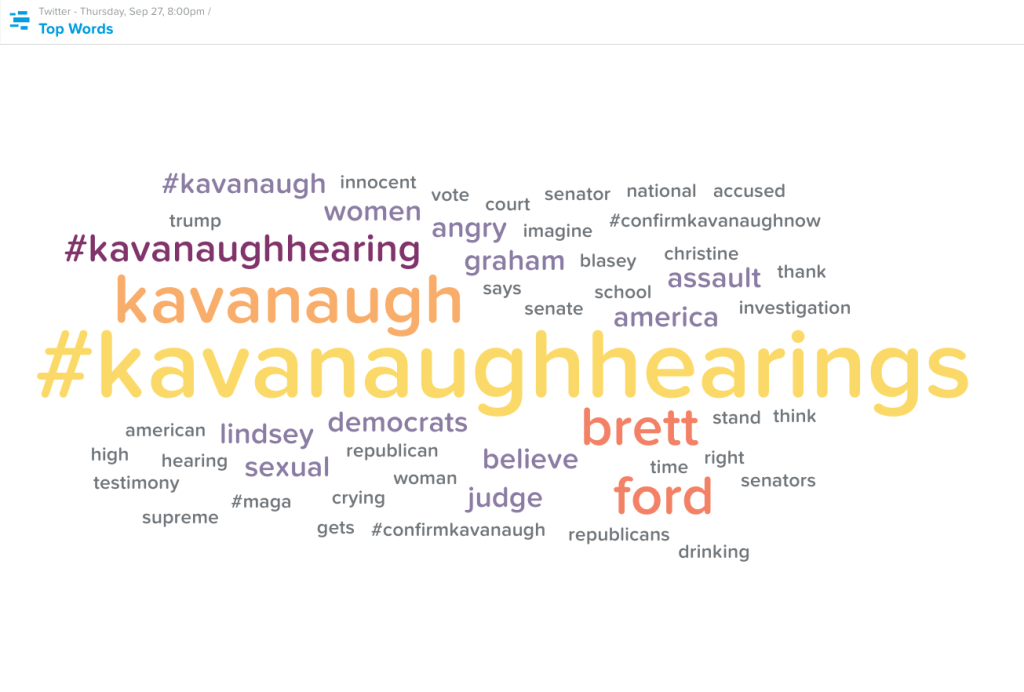

After exploring the context in which Trigger Block is set in, it is important to analyse its relevance in the new media world. Even though extensive research has been published on PTSD and trigger issues, this research is rarely linked to new media. Ysabel Gerrard’s work on eating disorders and social media can be seen as a good base to present the link between mental illness and social media. Her research emphasises the importance of moderating content online. She claims that some social media companies: “choose to moderate hashtags, block the results for certain tag searches and issue public service announcements when users search for troubling terms” (Gerrard 1). However, moderating sensitive content becomes more complex when users stay away from hashtags, or use “coded language” (Gerrard 17). This is especially demonstrated when algorithms moderate content, as it is “built into platforms’ closed codes” (Gillespie 11). This therefore explains why platforms encourage the use of hashtags, as non-tagged sensitive content is more difficult to find (Gerrard 6). The moderation of sensitive content can therefore have a key role for a social media user who suffers from PTSD, however, what is considered non-sensitive content by an algorithm, could trigger a user’s PTSD: “The concept of PTSD rests on the importance of buried memories, memory traces, which can be reignited as flashbacks (Heer). This can be demonstrated with an example, the recent #KavanaughHearings could be seen as simply referring to the hearings of a supreme court nominee. However, this hashtag could potentially trigger troubling flashbacks for sexual assault victims.

[Figure 1: Image representing twitter’s trending topics on September 27th, 2018.]

This is when Trigger Block’s functionalities become useful. Considering that it is impossible for an algorithm to identify which words and hashtags can trigger a person, Trigger Block is a tool that can be used depending on one’s needs. A sexual assault victim would therefore be able to block #KavanaughHearings, as well as #MeToo, which are seen as non-sensitive content by an algorithm. This puts content moderation in the hands of the users, enabling them to be in control of the words they do not want to see. Twitter already has a built-in tool which enables users to “mute” certain words on the platform. However, issues arise when a user blocks certain trigger words on twitter but encounters these same words on other social media platforms. Trigger Block being a browser plug-in, would work on all social media websites, as well as browser searches. The importance of a muting tool that covers different platforms is crucial, as it could prevent people who suffer from PTSD from unwanted traumatic flashbacks. Even though Trigger Block is specifically aimed at people who suffer from PTSD, this plug-in is extremely versatile. Sophie Hull wrote an article on “How to survive Mother’s Day when you’re grieving”, she explains that seeing the holiday being celebrated on social media can make it painful for someone who recently lost a family member. Trigger Block could be used to mute #Mothersday, and help someone who is grieving. The plug-in can be used in more mundane cases, as a parental control tool for example, so that parents can mute certain words they don’t want their children to see. Or even simpler, one could mute the name of a television show they are watching, in order to avoid spoilers. Overall, Trigger Block can be used to avoid flashbacks from people who have gone through trauma. This is a tool that can link the worlds of mental health and new media together.

Solution: An easy to use content blocking plug-in

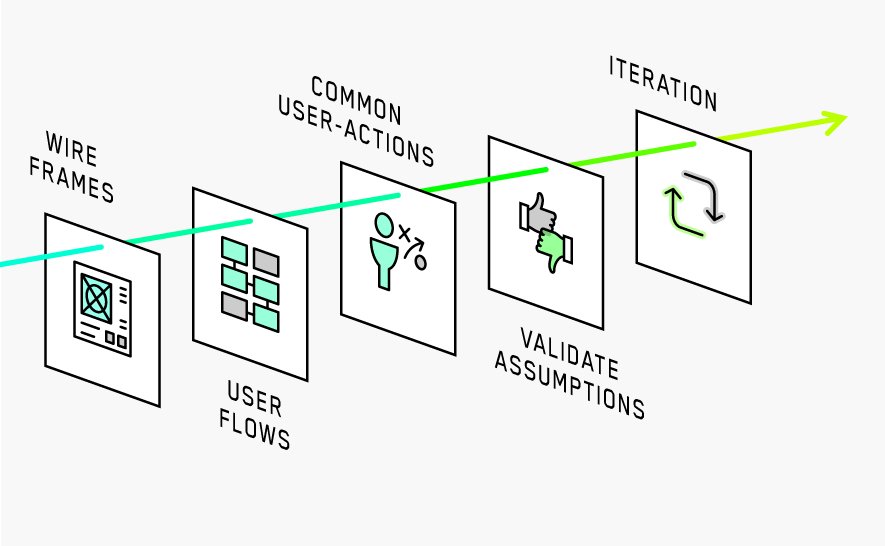

Due to the fact that this research is a conceptualisation of a web browser plug-in, we will not be creating the real plug-in. Instead, we will follow through a process to create a visualised version of the plug-in as shown in the steps below.

[Figure 2: Trigger Block plug-in logo. A chameleon representing transparency, and the camouflaging of trigger words.]

[Figure 3: Plug-in design process ]

1. Wireframing

For a browser plug-in to be effective, it must be easy to use. Functionally, we want the plug-in to be as natural to use as a search box in a web browser.

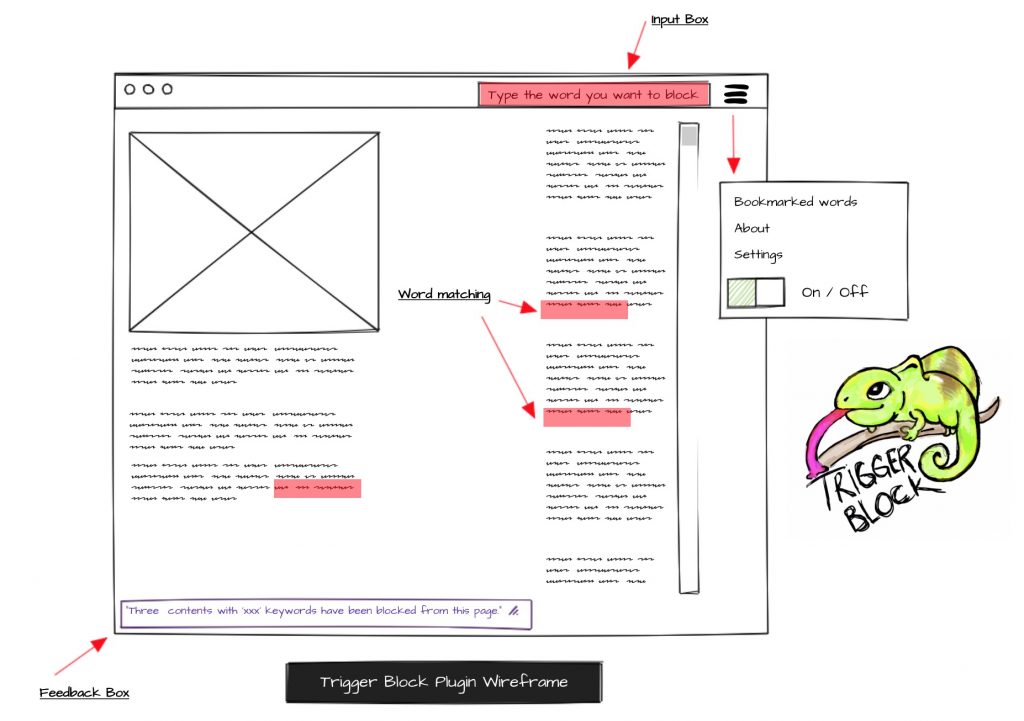

The first step is to think about the plug-in information architect. We draft the information flow for the plug-in to see what data and functionality need to be presented and how they will be organised. These will constitute the basic foundation of the wireframe.

After the information architect process is finished, we visualise the interface and assign each function to the menu. This will be done via pen and paper before transferring it to a digital wireframe tool as shown below.

[Figure 4: A visualisation of the Trigger Block wireframe, created with Mockflow.com]

The wireframe shown above represents the basic functionalities of the plug-in. Once the user installs the plug-in through a web browser or app store, a search box will appear at the top-right corner of the web browser window. It also includes a setting menu button. The user can input the word they want to mute and the plug-in will match contents that contain that particular word and hide it from the stream. In the setting menu, the user can bookmark frequently used words for later use as well as turning the plug-in on or off if need be.

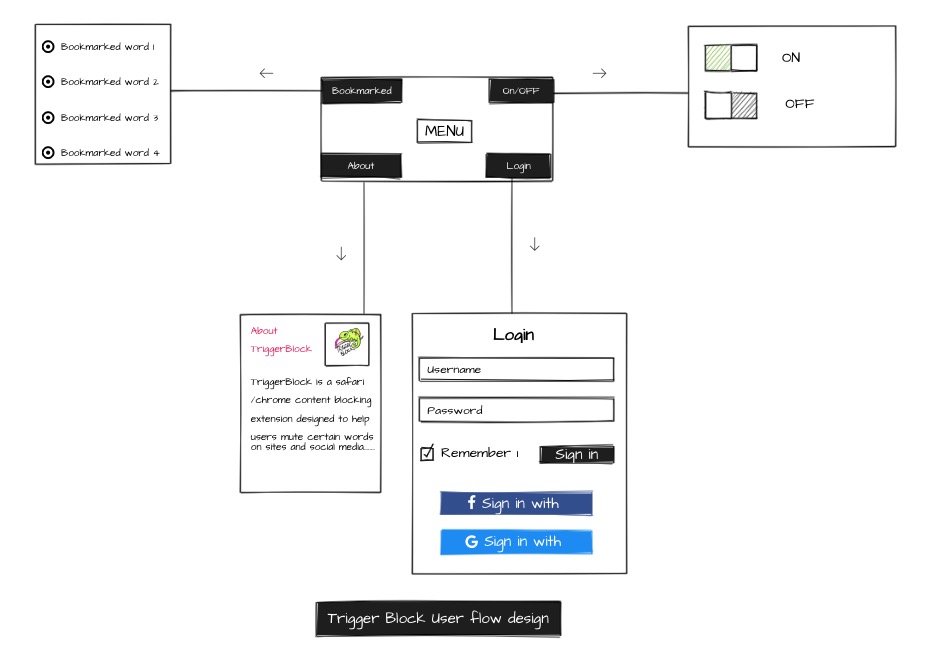

2. User Flow design

Once the basic wireframe is completed, user-plug-in interaction pathways must be designed. Since the plug-in functionality is rather narrow, the plug-in will not feature complicated interaction logic. A typical user pathway can be seen from the diagram below.

[Figure 5: Trigger Block plug-in user flow visualisation, created with Mockflow.com]

This process is crucial to create the most seamless plug-in experience and to make sure that the user will not be confused as to how the plug-in operates. The key consideration here is to have the least amount of settings possible.

There are four settings in the menu. The user can choose ‘bookmarked’ which will lead to frequently used keywords. On/Off toggle allows the user to enable or disable the plug-in even should the user want to turn off the plug-in while the search box in use. The about button provides concise information about the plug-in itself. Login button allows the user to register themselves into the system, which will allow all settings and stored keywords to be used across machines.

3. Validation Process

The final process is to test user flow to check if the plugin functions work as intended. While creating a functional web browser plug-in is beyond the scope of this research, we will examine plug-in validity through potential user feedback. This can be done through an interview with a wide-ranging group of potential users to check the user flow validity such as those with high technology literacy to those that barely use a computer. Then we use the feedback from the interview to further improve the plug-in functionality.

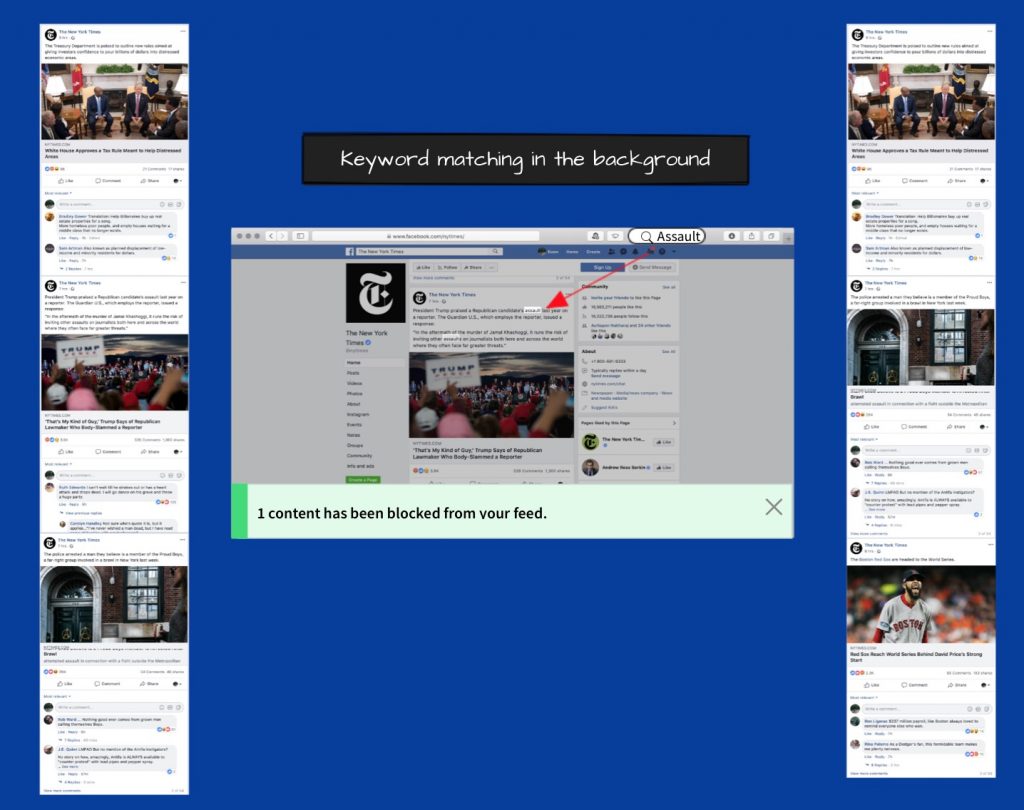

[Figure 6: A demonstration of how the plug-in works. The left column shows The New York Times Facebook Page feed. The center picture shows the the keyword (‘assault’) being matched. The user then receives a notification showing the number of content being hidden.]

4. Limitation

A conceptual project naturally involves certain limitations. Firstly, the time allotted for the project means we cannot create a working plug-in. Secondly, even if a working plug-in is created, it will take some time to be approved by browsers’ plug-in stores. Thirdly, without a working plug-in, it is not possible to test any potential errors or unexpected user behaviour. This limits our ability to imagine what could go wrong if the plug-in goes live.

Finally, Our plug-in would highly benefit from feedback from mental health professionals. A potential collaboration with “BetterHelp”, an online counselling platform with licensed therapists, would help us when addressing our plug-in to people who suffer from mental illness.

In conclusion, people who suffer from PTSD may encounter many trigger issues online. By analysing the disorder and exploring new media theory on algorithms and content moderation, it has been revealed that technology can be preventative in order to make life easier for people with mental illness. Even though the Trigger Block plug-in is a prototype and presents certain limitations, it is a step in the right direction to make users in control of what they see online. In controversial times when data and privacy issues arise, a new media tool could take the power from social media corporations, and give it back to online users.

Bibliography

“BetterHelp | Online Counseling & Therapy. Professional Counselling Services.” BetterHelp | Online Counseling & Therapy. Professional Counselling Services, www.betterhelp.com/

Bucher, Taina. “The Friendship Assemblage.” Television & New Media, vol. 14, no. 6, 2012, pp. 479–493

Cheney-Lippold, John. “A New Algorithmic Identity.” Theory, Culture & Society, vol. 28, no. 6, 2011, pp. 164–181

European Commission. “European Commission – Press Release Countering Online Hate Speech – Commission Initiative with Social Media Platforms and Civil Society Shows Progress.” European Commission, 1 June 2017, http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-17-1471_en.htm

Gerrard, Ysabel. “Beyond the Hashtag: Circumventing Content Moderation on Social Media.”New Media & Society, 28 May 2018. pp. 1–38.

Gillespie, Tarleton. Custodians of the internet: platforms, content moderation, and the hidden decisions that shape social media. (2018, Forthcoming) London; New Haven: Yale University Press.

Heer, Jeet. “Generation PTSD: What the ‘Trigger Warning’ Debate Is Really About.” The New Republic, 21 May 2015. 13th October 2018. https://newrepublic.com/article/121866/history-ptsd-and-evolution-trigger-warnings

Hull, Sophie. “How to Survive Mother’s Day When You’re Grieving | Sophie Hull.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 12 May 2018. 13th October 2018. www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/may/12/how-to-survive-mothers-day-when-youre-grieving

Martin, David M., et al. “The Privacy Practices of Web Browser Extensions.” Communications of the ACM, vol. 44, no. 2, Jan. 2001, pp. 45–50

National Institute of Mental Health. Mental Health Information, Statistics. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Nov. 2017, www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/mental-illness.shtml

“PTSD Self-Assessments Available To The Public As Part Of PTSD Awareness Day”. Mentalhealthscreening.Org, 2018, https://mentalhealthscreening.org/media/ptsd-self-assessments-available-to-the-public-as-part-of-ptsd-awareness-day. Accessed 15 Oct 2018.

“PTSD: Statistics, Causes, Signs & Symptoms | The Refuge”. Refuge, 2018, https://www.therefuge-ahealingplace.com/ptsd-treatment/effects-symptoms-signs/. Accessed 12 Oct 2018.

“What Are PTSD Triggers?”. Webmd, 2005, https://www.webmd.com/mental-health/what-are-ptsd-triggers#1. Accessed 16 Oct 2018.

Yeung, Karen. “‘Hypernudge’: Big Data as a Mode of Regulation by Design.” Information, Communication & Society, vol. 20, no. 1, 2016, pp. 118–136