Do the Robot: A critical alternative to gendered humanistic virtual assistants

“Alexa, how deep is the ocean?”, “Alexa play some music!”, “Alexa, call the plumber!” Mundane tasks such as making to-do lists, setting alarms, streaming podcasts, and searching for weather, traffic, sports, and other real-time information are all outsourceable in the smart home. Artificial Intelligence (AI) based virtual assistants, like Amazon’s Alexa, are home automation devices and are called upon to access their respective databases to provide answers or perform functions instantaneously, it seems all you have to do is… “just ask”.

With tech giants each rolling out their own virtual assistants, namely Amazon’s Alexa, Microsoft’s Cortana, Google Assistant, and Apple’s Siri, it is clear that virtual assistants are steadily gaining popularity. In a 2018 article, Forbes states that over 30 million smart speakers were sold globally last year, (of which Amazon’s Alexa sold about 20 million devices) and this number is expected to rise to approximately 60 million this year (Marr, October 2018)

While these voice assistants certainly provide many conveniences, what is noteworthy is that the default voice chosen for each of these AI assistants is, in every instance, a female human voice. (Liberatore, October 2018). While this may seem inconsequential at first glance, Neil Postman, in a keynote address on the topic of The Humanism of Human Ecology underscored the importance of a medium by stating, “A medium is a technology within which a culture grows; that is to say, it gives form to a culture’s politics, social organization, and habitual ways of thinking.” (Postman 2000:10)

Our research focuses specifically on Amazon’s Alexa and examines the significance and effects of the female and human-like quality of her voice. We propose a playful intervention in the form of an application called Do The Robot which aims to draw awareness to these generally unquestioned design choices by asking the question:

Can we reimagine the voices of AI virtual assistants to counteract gender biases and disrupt human-machine interactions?

Why does Alexa have a female voice? And why is “she” human?

The major technology companies, Apple, Amazon, Microsoft, Facebook and Google are all advocating the use and integration of human, female-voiced AI virtual assistants into consumer’s home life. All of these companies operate on ‘surveillance capitalism’ based business models. Surveillance capitalism is a term coined by Professor Shoshanna Zuboff of Harvard University, which describes the extraction, control and monetization of consumer’s behaviour and data, while producing new modes of behavioural prediction and modification.This business model is important when considering the introduction of virtual assistants and their design by these companies. (Zuboff 2015)

In her recent work, Dr. Heather Susanne Woods, directly related Zuboff’s model of surveillance capitalism with the growing use of female voice for virtual assistants by technology companies. Her article, Asking More of Siri and Alexa: Feminine Personas in Service of Surveillance Capitalism, suggests that the digital domesticity of the female human voices used in virtual assistants creates “devices that both execute tasks and build relationships is a strategic move for surveillance capitalists, who may mobilize this reliance to gain access to increasingly intimate types of information about their users, and then extract and alienate the data from consumers.” (Woods, 2018).

The commercial benefits of consumers adopting commercial virtual assistants cannot be overstated. In an article for the Venturebeat website, journalist Clement Tussiot, states that the human voice is the most natural interface for humans, and its use enables the building of deeper relationships between customers and the brand itself. This voice technology allows Google and Amazon to move from text-based interactions with their users. The more human, vocal aspect of Alexa and other virtual assistants allows them to engage in the personal lives of their users and build deeper levels of trust between the corporation and the consumer.

In the MIT technology review, Stanford associate professor, Sridhar Narayanan, described the potential for AI virtual assistants, like Alexa and Google Assistant, to create a “deeper user profile” for their respective companies. He asserted that “a back-and-forth conversation with Google’s Assistant about, say, vacation destinations could reveal more about what you want and like than a handful of conventional searches, particularly when combined with other information Google is able to access about consumers.” (Simonite, October 2018). This is further corroborated in Amazon’s plans to roll out Alexa Hunches later this year. This will see Alexa replicate human hunches by monitoring daily behaviour and using deep neural networks to produce likely guesses and predict user’s future needs (Liao, October 2018).

Virtual Assistants, like Alexa, also encourage frictionless purchasing from its users (Rheude, February 2018). This feature directly relates to a key attraction of virtual voice assistants – their ability to increase money spend from it’s customers. According to data from Consumer Intelligence Research Partners, in 2017 American Amazon Echo owners spent on a regular basis around $1700 a year. That is a lot more than the non-prime regular Amazon U.S customer, who spend around $1000 on average (Weissman, March 2018). These examples illustrate the potential these devices have to increase customer spending and loyalty.

Because of the commercial benefits of human-voiced virtual assistants, companies have done significant research into how to make the voice of an assistant attractive and comfortable to use for consumers. Female human voices were chosen based on research on how humans respond to gendered voices. Studies conducted by Communications Professor, Clifford Nass, concluded that users “tend to perceive female voices as helping us solve our problems by ourselves, while they view male voices as authority figures who tell us the answers to our problems” (Hempel, October 2018).These perceptions are significant when the primary interaction users have with virtual assistants are question based. The choice of a female voice gives the user a greater feeling of control over the interaction. Women are also more commonly associated with administrative and domestic tasks which correlate with the function of the virtual assistants. It makes commercial sense to choose a female voice as a default, which consumers have been shown to prefer.

Interactions between humans and Alexa are command based and AI virtual assistants are designed to complete all tasks, without question, to satisfy the user. The tag line for Alexa is “Just Ask”, reflecting this purpose. Andrea Guzman, who has a Ph.D. in Communication studies, focuses her research on human-machine communication and notices that the manner in which Siri, and by extension, Alexa, are designed to activate and function, operates through command based language such as “Siri, call Brian” or “Alexa, play Thriller ” (Guzman p. 9, 2018). This encourages users to interact with the assistant authoritatively, giving the user a feeling of control.

Why is this significant?

Source: https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2018/01/sorry-alexa-is-not-a-feminist/551291/

The choice of a female voice for a non-human algorithmic entity, whose principle purpose is obedience, raises uncomfortable questions for the use of this technology and its potential to re-establish harmful societal stereotypes for human women, who are commonly associated with personal assistant roles. In her article, The Real Reason Voice Assistants Are Female (and Why it Matters), Steele highlights this point when she says “When we can only see a woman, even an artificial one, in that position, we enforce a harmful culture.” Ironically, when asked, Alexa does identify as feminist, which directly contradicts her apparent function, which is simply to do exactly what the user requests (Carton, June 2018).

The human voice, male or female gendered, of voice assistants like Alexa also brings up questions of class through the choice and tone of accents used. When discussing Alexa’s voice, it is pertinent to acknowledge the designers’ choice of accent, a quality inherent in human speech. Accents are a signifier of class and origin. The academic, Gerry MacRuairc, in his book They’re my words – I’ll talk how I like! Examining Social Class and Linguistic Practice Among Primary School Children, theorizes that a speaker’s linguistic style can be seen as a behavioral creation of cultural identity and describes language as a tool to transfer ideas, express feelings and engage in interaction.

The choice of accent for a virtual assistant has societal meaning, particularly given that, according to Chandra Steele, in PCmag that when users communicate with AI voices, like Alexa, they unconsciously try to ‘linguistically style match’ the language and accents of these AI. The accents chosen for virtual assistants are clear, but often derivative of the accents of the patrician class of a given language. Users changing their accents in order to be understood by virtual assistants, could have normative effects on language and implications for the rich variety of accents which naturally occur among humans.

Source: https://techcrunch.com/2017/08/31/amazon-adds-parental-consent-to-alexa-skills-aimed-at-children-launches-first-legal-kids-skills/

The combination of the human-voiced virtual assistant (male or female) and the command based language used to activate them, has implications for their most enthusiastic fans: children. Parents have become increasingly uncomfortable with children’s use of authoritative language when interacting with human voiced AI, particularly with Alexa (Shellenbarger, October 2018). In a Wall Street Journal piece on Alexa’s relations with children, the parent and Silicon Valley venture capitalist, Hunter Walk, was quoted expressing this concern: “Cognitively, I’m not sure a kid gets why you can boss Alexa around but not a person.” (Shellenbarger, October 2018)

This year, Amazon introduced Alexa’s new feature for children to quell these concerns, named Kids Manners. This feature does not consider the human qualities of Alexa’s voice, but instead targets the use of commanding language – the aspect fundamental to parents’ concern. Kids Manners raises questions about the relationship between children and machines, by requiring children to say ‘please’ and ‘thank you when making requests’, which encourages the anthropomorphizing of Alexa by children. We do not teach children to be polite to an Amazon search bar, however the human quality of Alexa’s voice leads us to extend human social norms to it, reinforcing it as a human equivalent. Amazon’s introduction of manners has led to some critics, like Mike Elgan to argue: “In teaching children to treat machines like people, we may also be treating people like machines” (Elgan, July 2018).

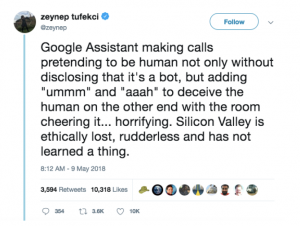

In a livestreamed demo of Google Duplex, a voiced AI program designed to book appointments, illuminated concerns over the unquestioned and unregulated use of human voices for artificial intelligence. The test presented the program’s ability to book appointments and converse with a human worker without being detected as an AI. The Google Duplex program, using a female voice which was programmed to use human speech characteristics (“umm” and “eeh”), was tasked to call a hairdresser to make an appointment in front of a live audience, without being detected as a non-human (Vincent, October 2018).

This deception received criticism from many, including Professor Zeynep Tufekci, a prominent new media academic:

Source: Twitter

Following criticism, Google edited the program, requiring it to identify itself to any recipient of phone calls. However, Google’s self regulation, in this case, highlights the absence of ethical debate and regulation of how AI virtual assistants should be presented, now and in the future. This is important to note as voiced AI, like the Google Duplex, and even Alexa are projected to play a consequential role in society.

Intervention: Do the Robot

The principle fault we find with AI virtual assistants resides in its gender and humanised design. While Apple’s Siri, Google Assistant and Cortana now offer male voices as an option on their devices, these alternate voices are never the default option and can require a four (or more) step process in order to change them (Jansen, October 2018). This affects consumer behaviour because there is substantial evidence to prove that the majority of people are affected by the “status quo bias” and have a tendency to stick with the default option (Thaler and Sunstein p.7, 2008).

This solution is inadequate as it fails to address the humanized machine interactions presented by still having a human sounding voice. The default human female voice of commercial AI was chosen to appeal to consumers to maximise commercial profit of the companies which design them, but in doing so, humans have been denied the opportunity to engage in the ethical implications of humanising AI. The status quo and humanisation of this design is significant, because virtual assistants are many users’ first interaction with artificial intelligence. How virtual assistants are designed and promoted by commercial companies will possibly inform how humans interact with commercial AI and what they expect from it in the future.

To intervene, we ask the question: Should a non-human, commercial entity, be given human characteristics at all?

Our intervention, named Do the Robot, is a free for download application that address the issues of gender biases and human-machine relationships by transforming the voices of virtual assistants, like Alexa, into synthesized robotic voices. Our prototype will exclusively target Alexa because Amazon’s Alexa is available on a variety of hardware including Android, IOS, Amazon products and now Facebook’s Portal. This vocal transformation underscores the technological nature of the commercial entities that consumers are being encouraged to integrate into their lives and thus brings about awareness by disrupting the status quo.

How does it work?

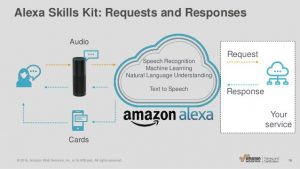

Source: https://chatbotsmagazine.com/how-does-alexa-skills-works-82a7e93dea04

To understand how Do the Robot will intervene in Alexa’s speech, it is important to comprehend how it functions: Alexa is activated by the wake word, which signifies the start of a request. It then starts recording your voice and when you have finished speaking, it uses an internet connection to send this recording to Amazon, which in turn gets processed by Alexa Voice Services (AVS). This translates the recording into commands, which Alexa then interprets.

The intervention occurs at the final stage of Alexa’s response process, right before it verbally answers a request. Do the Robot will capture and transform the digital sound of the female voice into an analog sound resulting in a genderless, robotic voice. This process happens in real time, ensuring the user does not experience a delayed response from Alexa.

Interactions between the user and Alexa will not be recorded or stored on the Do The Robot servers, which will provide security to users and assure their privacy when using this application. Users actions, requests and data which are collected by Alexa remain solely between the user and Amazon. Do the Robot is a voice converter and does not affect Alexa’s functions beyond its voice.

Above: The mobile interface of Do The Robot.

Above: The desktop interface of Do The Robot showing the simple design and easy to use functionality.

Once the application is installed on the hardware, mobile or computer, the app automatically syncs with Alexa and activates the voice convertor. This voice converter can be disabled at any time by clicking the “off” button in the application. When the application is deleted from the user’s phone or computer, it will restore the default female Alexa voice function.

Alexa, conclude this for me, but in a robotic way

By disrupting the default of the human female voice and replacing it with a robotic one, Do The Robot encourages users to reflect on the gendered and humanised dynamics of these virtual assistants. Do The Robot aspires to spark conversations about the adoption of commercial voice-based technology into the infrastructure of our homes and lives. We want to make it as easy as possible to intervene, therefore we are creating an app that targets Alexa. In getting virtual assistants to ‘do the robot’ we hope to open discussions about the design of AI and how we, as humans want to relate to and interact with commercial AI in the future.

“Alexa, do the Robot!”

References

Bagueley, Richard, and Colin McDonald. “Appliance Science: Alexa, How Does Alexa Work?.” CNET. N.p., 2018. Web. 19 Oct. 2018.

Carton Geraldine, “Have you ever noticed how ALL ‘virtual assistants’ have female voices?”, Image.ie, 29th June 2018, https://www.image.ie/life/virtual-assistants-female-122273, Accessed: 12th October 2018.

Elgan, Mike. “The Case Against Teaching Kids To Be Polite To Alexa.” Fast Company. N.p., 2018. Web. 19 Oct. 2018.

Guzman, Andrea L. “Making AI safe for humans: A conversation with Siri.” Socialbots and Their Friends. Routledge, 2016. 85-101, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/301880679_Making_AI_Safe_for_Humans_A_Conversation_With_Siri, Accessed: 12th October 2018.

Hempel, Jessi. “Siri And Cortana Sound Like Ladies Because Of Sexism.” WIRED. N.p., 2018. Web. 19 Oct. 2018.

Jansen M., “How to change Google Assistant’s voice on your Android or Apple phone”, 14 May 2018, digitaltrends.com, https://www.digitaltrends.com/mobile/easy-guide-on-how-to-change-google-assistants-voice/, Accessed: 19th Oct. 2018.

Liberatore Stacy, “Why Al assistants are usually women: Researchers find both sexes find them warmer and more understanding”, Dailymail.com, 24th February 2017, https://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-4258122/Experts-reveal-voice-assistants-female-voices.html, Accessed: 8th October 2018.

Liao S. “Alexa Hunches Can Now Suggest Actions Based On Daily Behavior”. The Verge, 2018, https://www.theverge.com/2018/9/20/17883396/amazon-alexa-hunches-prediction-smart-home-ai. Accessed 19 Oct 2018.

MacRuairc, Gerry. “They’re my words–I’ll talk how I like! Examining social class and linguistic practice among primary-school children.” Language and Education 25.6 (2011): 535-559, https://www.pri.org/stories/2018-03-28/meet-pegg-gender-neutral-robot-assistan, Accessed: 12th October 2018.

Marr, Bernard. “Machine Learning In Practice: How Does Amazon’s Alexa Really Work?.” Forbes. N.p., 2018. Web. 19 Oct. 2018.

Postman, Neil. “The humanism of media ecology.” Proceedings of the Media Ecology Association. Vol. 1. No. 1. 2000.

Rheude, Jake. “Her Name Is Alexa And She’s Changing How Your Customers Shop.” Forbes. N.p., 2018. Web. 19 Oct. 2018.

Shellenbarger, Sue. “Alexa: Don’T Let My 2-Year-Old Talk To You That Way.” WSJ. N.p., 2018. Web. 19 Oct. 2018.

Simonite, Tom. “Virtual Assistants Like Alexa And Google Assistant Will Feed Tech Giants Valuable New Data About Us.” MIT Technology Review. N.p., 2018. Web. 19 Oct. 2018.

Steele Chandra, “The Real Reason Voice Assistants Are Female (and Why it Matters)”, pcmag.com, 4th January 2018, https://www.pcmag.com/commentary/358057/the-real-reason-voice-assistants-are-female-and-why-it-matt, Accessed: 10th October 2018.

Steele Chandra, “The Real Reason Voice Assistants Are Female (and Why it Matters)”, medium.com, 29th January 2018, https://medium.com/pcmag-access/the-real-reason-voice-assistants-are-female-and-why-it-matters-e99c67b93bde, Accessed: 12th Octobober 2018.

Tussiot, Clement. “Voice Technology Will Change Your Relationship With Customers.” VentureBeat. N.p., 2018. Web. 19 Oct. 2018.

Vincent, James. “Google’S AI Sounds Like A Human On The Phone — Should We Be Worried?.” The Verge. N.p., 2018. Web. 19 Oct. 2018.

Weissman, Cale Guthrie. “Amazon Echo Owners Spend More On Average Than Prime Members”. Fast Company, 2018, https://www.fastcompany.com/40513159/amazon-echo-owners-spend-more-on-average-than-prime-members. Accessed 19 Oct 2018.

Woods, Heather Suzanne. “Asking More Of Siri And Alexa: Feminine Persona In Service Of Surveillance Capitalism.” Critical Studies in Media Communication 35.4 (2018): 334-349. Web.

Zuboff, Shoshana. “Big Other: Surveillance Capitalism And The Prospects Of An Information Civilization.” Journal of Information Technology 30.1 (2015): 75-89. Web.