Cookie Monster: building awareness around free labour and data-exploitation

Introduction

Users that roam the European Internet on a daily basis will have come across them countless of times. Each time a new website is visited it pops up in the middle of the screen or it rests in the corner of the website in the form of a banner: a cookie notice. It asks you for your consent to the use of cookies. What these cookies may actually entail remains unknown for the majority of its visitors. For the majority of users, the cookie notice is just an annoying pop-up that blocks their view. Clicking the ‘I accept’ button as quickly as possible, and thus allowing these tracking cookies, has become just another part of their everyday browsing ritual.

The spur of cookie consent requests on nearly every website is a consequence of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) that came into effect earlier this year. The regulation is there to protect user privacy in the digital realm: tracking cookies may only be used if the user consents first. In theory, this regulation should give users more control over their own data. However, the problem here is that users still do not have an easy possibility to actually opt-out of this practice. Most users blindly accept the cookies and continue on with their browsing activities. The moment the cookie, a text file that ‘memorizes’ things about websites, is placed upon a browser, access is granted to first and third parties to collect, store and analyze possibly every movement from that point on. Moreover, websites are even able to track users across the web: social media sites such as Facebook are generating enormous profits just by selling data that they extracted from their users. The user-generated content and browser activity thus creates value, but there is no monetary compensation for this. In a sense, the audience performs free digital labour. Users now function as both consumers and creators of media products.

With our project, we aim to make users of Web 2.0 aware of the fact that they are in a sense part of a digital labour system and that their personal data is being “exploited” by third parties through the use of cookies. There still remains a lack of transparency within this practice and general knowledge about different types of cookies and what they do is still quite scarce. As Yeung points out, there exists what Nissenbaum has called a ‘transparency paradox’ within the practice of third-party tracking right now: people must be informed about what kind of data is being collected and for what purposes (Yeung, 126). However, to avoid information overload, the information that is provided is often not very detailed. Yeung emphasizes that most users within the Big Data environment are not fully aware of what they are actually sharing, but are focused on the convenience and efficiency that digital services have to offer. (Yeung, 126). Our project, “Cookie Monster”, is designed to make users more aware of what the ‘I accept’ button means for their personal data and to assist them in making an informed decision about cookies via a plug-in and a website. The goal of our technological intervention would ultimately be to bring awareness to how much of our data is being used without our knowledge and to show people the ways to protect themselves from these forms of data-exploitation.

First, we will frame the issue of third-party tracking by discussing the notion of free labour through various literary work. Secondly, the methodology section will further elaborate on how the plug-in and website were designed and how the data for this was accumulated. Then the Cookie Monster plug-in and website will be introduced and finally a conclusion will be given.

Allowing cookies: a form of free labour?

The classic form of labour took place within the traditional environment of the firm or factory (Lazzarato, 4). However, the rise of the Internet has defined new forms of labour that can take many different shapes and sizes. As opposed to the classic or traditional form of labour, immaterial labour in the digital media environment takes place in the society, in a system of networks and flows (Lazzarato, 4). We can apply this shift to the the “society-factory” that finds its roots in Italian Marxist theory (Gill & Pratt, 1). Terranova links the “society-factory” to the digital economy and broadly defines it as “a process whereby work processes have shifted from the factory to the society” (34). As Terranova argues, the Internet is not an empty space: it includes forms of cultural and technical labour that produce a continuous flow of labour that is inherent “to the flows of the network society at large” (34). This new economic system of the digital economy has important implications for the way that labour is defined in advanced capitalist societies. In the age of the digital economy, the source of added value is generated by users (Terranova). In a sense, personal behavioral data that is continuously being created by users has actually become a currency itself. (Libert, 3544).

By surfing the web and generating content online, everyday users of the Internet are generating large amounts of valuable data for companies. Scholz mentions waged and unwaged ‘digital labour’ and explains that this concept can entail activities from writing fanfiction or “game modding” for example (1-2) or, as in our case, ‘producing’ data for third-party advertisers. Personal information such as browser activity and user-generated content, but also user settings, information about previous purchases etcetera is turned into value. However users are not being compensated for the “labour,” i.e. time and effort, they have put into this. The exploitation of personal data for commercial and profiling purposes has grown to be a big part of the digital economy. A large quantitative analysis conducted in 2015 indicated that nearly nine out of ten websites leak user data to parties of which the user is most likely unaware and that third-party cookies are placed on over six in ten websites (Libert, 3544). The labour that is being performed can be viewed as free labour, because it generates value. As Read has pointed out, (potential) labour in the age of neoliberal capitalism can be any activity that works towards desired ends (Read, 8).

Relevance

Our aim with this research is to create awareness and to make visible how much valuable data users produce every day and how little users are actually compensated for this. Users are usually unaware of the fact that their every movement is being monitored by third-party tracking devices on the entire web. Most users would for example be unaware that even if they visit health-related websites their browsing data is being passed on to third-party entities. We want to show users how essential audience labour power is to corporations, as they function as both consumers and creators of media products. Furthermore, we to make all kinds of everyday users of Web 2.0 aware of the current existing technologies and methods they can actually implement to circumvent the tracking of their data in a simple way. By building this type of awareness we are showing users the ways in which they can gain back some control over their personal data in a world where data-mining is an ever growing practice.

Methodology

The objective of Cookie Monster relies largely on a literary review of free labour. The literature was found in the Google Scholar database by searching for the keywords “free labour” and “immaterial labour”. Not every literary source explicitly mentioned the connection between their notion of labour with the digital aspect, but this is done on purpose to provide a clear picture of the full academic debate around free labour. The plug-in for Cookie Monster was designed with the digital design application called Sketch. The data that is shown in this plug-in is retrieved by two different already existing applications: Data Calculator by Datum and Ghostery by Evidon Inc. The Data Calculator is developed by Datum draws on available information from both public as well as privately-owned companies, and information that their companies as gathered at trade shows (Theo, n.pag.).

For the designing of the mock-up of the website Cookie Monster, we used the website building platform, Wix. The information about the cookies has been found through Google search.

Cookie Monster

With the increasing computerization of our world, it is important to bring attention to the commodification and exploitation of users online data. More than three billion people have access to the Internet and the number of people that roam the Web on a daily basis will most likely only continue to grow. Most of these people are either unaware that their data is being tracked and for which purposes, or ill-informed about this phenomenon (Tuunainen, Pitkänen & Hovi, 9). In the context of Neoliberalism, the Internet has given people the freedom to participate online without showing them how these online activities benefit the accumulation of capital for corporations. While social media provides the space for open communication, the cultural capital produced by consumers is seen in economic terms that are motivated by the desire to accumulate money. Social media platforms, such as Facebook and Twitter, depend on its users to produce content that can be leveraged and sold to advertisers for profit. This can also be seen as a form of free labour.

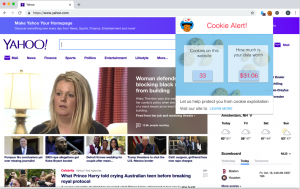

Cookie Monster is designed to raise awareness about what cookies are on the visited website, how they work and how much value is generated from them. It takes the form of a plug-in that can be added to your browser which shows you how much your extracted data is worth and how many cookies are placed (figure 1). By revealing the actual worth of the users’ data, Cookie Monster aims to raise awareness about the free labour aspect of sharing your data as a user. The plug-in also shows how many cookies are placed to show that there can be many and that. Additional to the plug-in, there is a general website with basic information about cookies and their implications. This website contains information about various types of cookies and their purposes, but also proposes options that can protect the user while roaming the Internet.

Cookie Monsters’ aim to raise awareness about this issue but also make the information more accessible to the general public. Most of the existing information that is available about how cookies work and what their implications are might not always understandable to for the not digitally natives and/or have a subjective tone.

The website includes the EU regulations since Cookie Monster is catered specifically to European users that are affected by the new cookies laws. Firstly, the website explains what a cookie is: it is a small text file that is placed on the users hard drive when they visit a website and is used for storing information about users. Secondly, the different types of cookies are explained. The EU law namely distinguishes between two types of cookies: session and persistent. Session cookies are strictly required for website functionality and don’t track user activity once the browser window is closed. Persistent cookie however, do track user behavior even after a user has moved on from the site or closed the browser window. It is important that users know the difference between these, because these persistent cookies can pose a greater risk than session cookies, since they can track your activity over time on multiple websites.Cookie Monster also explains what cookies are used for: how websites use cookies to store your preferences, such as your username and password – and then how advertisers use the information stored in cookies to create unique profiles for targeting users (Penland, n.pag.). Finally, Cookie Monster gives users the option to protect their privacy. These options include different ways that users can avoid cookies tracking their data, for example links to install internet security software, or a company called Evidon created a consolidated link of the most common third-party cookies where you can opt-out of all of them.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Cookie Monster Website: https://danalamb3.wixsite.com/cookiemonster

Conclusion

The introduction of Web 2.0 has essentially allowed companies to profit off of users activities online. With this project we wanted to evaluate how corporations are able to use cookies to identify people and track their online behaviour. Companies are now starting to be held accountable for their practice of data collection as the new European Cookie Laws make all platforms display notices on their sites when Cookies are placed to track users movements across the web. While some of these notices may provide users with the opportunity to read more about what cookies are, this information is often presented in long and confusing text. Therefore, most people just accept cookie notices without understanding the implications.

By creating Cookie Monster, our hope is to make the public aware of their involvement in a process of unwaged labour where everything they post online is monitored and analyzed in the form of data and then sold to tertiary parties. As many users accept Cookies without a second thought, we want to show them that these seemingly harmless text files may be invading their personal privacy. While not all Cookies are dangerous, it is important for users to understand who has control over their personal data and how much of their lives are being tracked and exploited. Users should not feel as though they need to block cookies all together, and in fact this could make it almost impossible to effectively browse the web. Rather, we want to pass along important knowledge about cookies in a succinct and easy-to-understand format. For example, demonstrating to users that only certain cookies involve tracking personal information and simply turning of third-party cookies can diminish the possibility of private data being spread to unintended parties. There are several ways to circumvent the threat that cookies pose to users privacy, and through Cookie Monster, we want to teach the public how to keep their information safe.

Bibliography

Gill, Rosalind and Andy Pratt. “In the Social Factory? Immaterial labour, Precariousness and Cultural work.” Theory, Culture & Society 25.7-8 (2008): 1-30.

Lazzarato, Maurizio. “Immaterial Labor.” Radical Thought In Italy: A Potential Politics 1996 (1996): 133-47.

Libert, Timothy. “Exposing The Hidden Web: An Analysis of Third-Party HTTP Requests On One Million Websites.” International Journal of Communication 9. (2015): 3544-3561.

Penland, Jon. “What’s The Deal With Cookie Consent Notices.” WPMUDEV. 17 June 2016. 15 August 2018. <https://premium.wpmudev.org/blog/cookie-consent-notices/>

Read, Jason. “A genealogy of homo-economicus: neoliberalism and the production of subjectivity.” A Foucault for the 21st century: Governmentality, Biopolitics and Discipline in the New Millennium. Ed. S. Binkley & J. Capetillo-Ponce. Newcastle Upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholar Publishers, 2016. 2-15.

Scholz, Trebor. “Why Does Digital Labor Matter Now?” Digital Labor: The Internet as Playground and Factory. Ed. Trebor Scholz. New York: Routledge, 2012. 1-9.

Terranova, Tiziana. “Free Labor.” Digital Labor: Digital Labor: The Internet as Playground and Factory. Ed. Trebor Scholz. New York, NY: Routledge, 2012. 33–57.

Theo. “How Much Is Your Data Worth? Datum Calculator Answers Your Questions.” Datum Blog. Datum. 6 November 2017. 15 Oktober 2018. <https://blog.datum.org/how-much-is-your-data-worth-datum-calculator-answers-your-questions-f8fb38575153>

Tuunainen, V. K., O. Pitkänen, and M. Hovi. “Users’ Awareness of Privacy on Online Social Networking sites-Case Facebook.” Bled Conference, June 14-17, Bled, Slovenia. 2009.

Yeung, Karen. “‘Hypernudge’: Big Data as a mode of regulation by design.” Information, Communication & Society, 20. (2017): 118-136.