You Won’t Believe What These Young Liberal Students Did Their Project On

Fake news

When Pheidippides burst into the Greek assembly to exclaim ‘nenikēkamen’, after running from the battle of Marathon to Athens where the Greeks had just conquered the Persians, his death gave birth to the concept of the marathon sporting event which still prevails. The problem is, we actually don’t know if his name was Pheidippides. Plutarch for example gives him several different names, other stories claim that the Greek army returned from the battle to the undefended Athens to inform them of the victory and that it was not the young man after running the vastly debated 240 km to get there. Or was it 40 km, or was it 35 km, or did he go to Sparta and not Athens at all?

Misinformation has been around for thousands of years, and has given birth to many modern phenomenon like the marathon, footnotes, Christmas, and Donald Trump’s presidency. ‘Fake news’ is one of the former reality tv-show host’s favourite words, along with “fake books”, “the fake dossier”, and “fake CNN”. However, like the distance from Marathon to Athens, our definition of ‘fake news’ and ‘misinformation’ is changing and expanding every day. ‘Fake news’ no longer applies to just blatant misinformation, but to a tactic, a style of writing and language, which is becoming increasingly harder and harder to notice or even care about. Everyone ‘thinks’ that they know what fake news is; it’s a website with an unregistered domain, it’s an article that pops up when you’re on another website illegally watching The Office US, it’s a headline that says ‘How Colleges Fail Young Trump Supporters’ or ‘You Won’t Believe the Secret in Traveling to Your First Half-Marathon, And Successfully Finishing’, but these last two headlines are from trusted news sources The Republic and Forbes Magazine, according to my fake news plug-in Trusted News. Both of these articles are ‘true news’: they contain facts and quotes from reputable databases and sources. Yet fake news linguistic tactics in the wording of the articles titles (clickbait) were used to entice you to click on it, generate revenue for the website, but then leave when you were bored, adding to the additional fake news arch of the ‘click-and-go’ economy. Talking to The Verge, Sarah Roberts, Assistant Professor of Information Studies at UCLA, said that ‘[i]n the era of abundant information, people need that expertise now more than ever”, to detect what makes fake news, fake. Enter our application: Trumpeter.

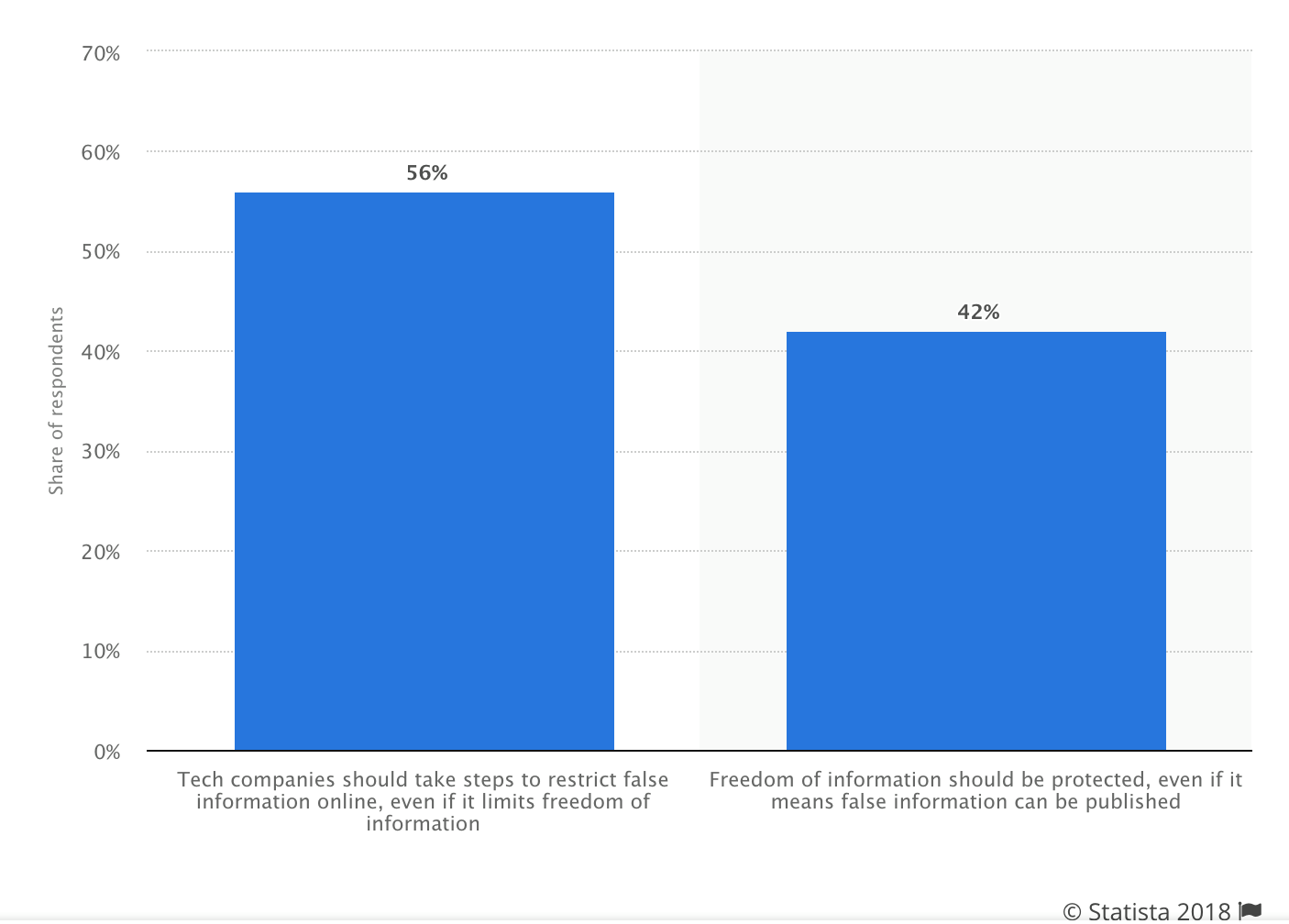

Image 1: This statistic shows public opinion on tech companies restricting fake news online in the US in 2018. 42% stated that freedom of information should be protected, even if it means false information can still be published.

Fake News Plug-ins

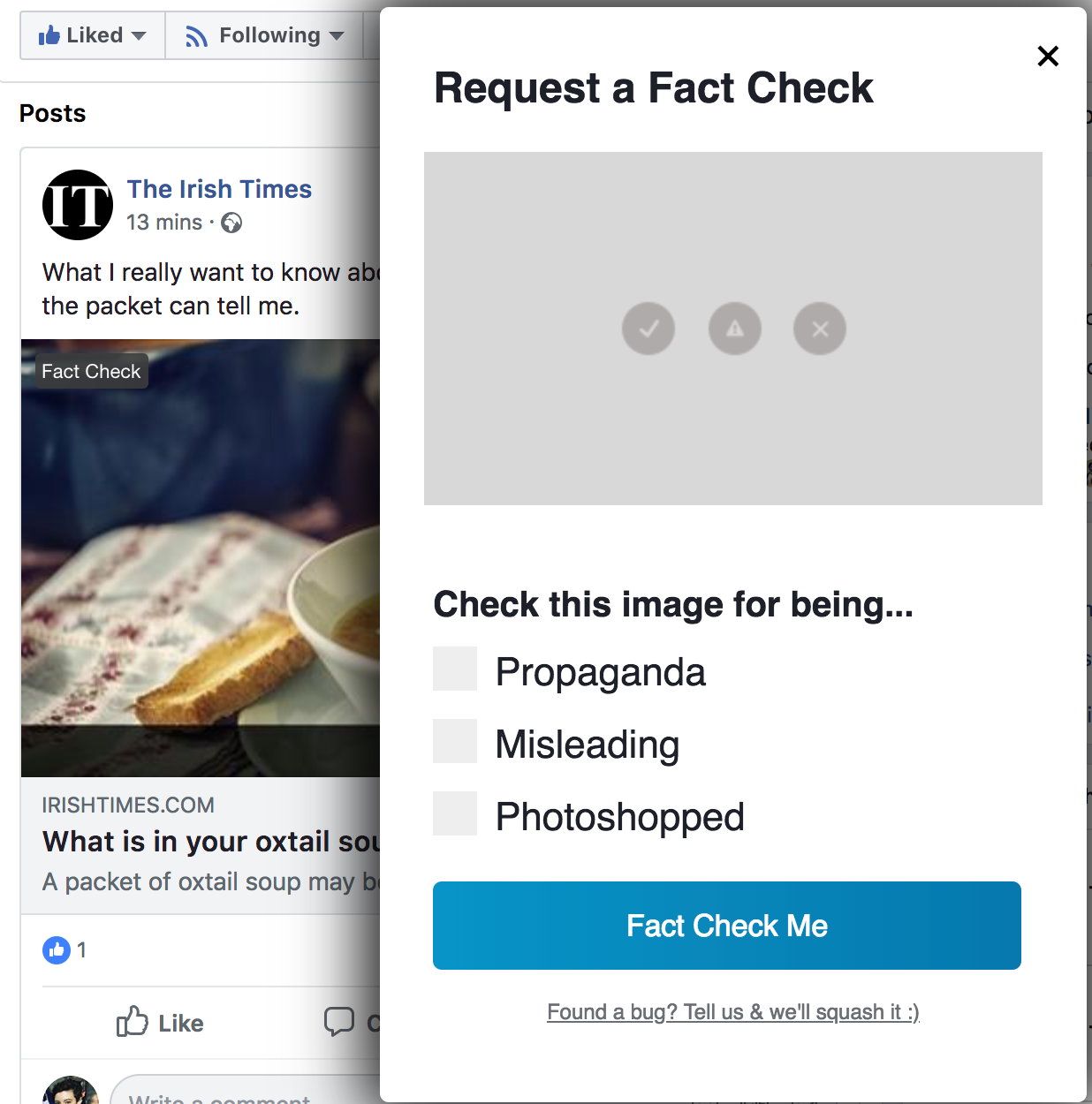

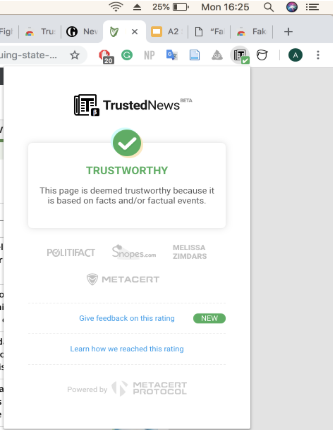

‘Fake news’ is a far reaching phenomenon with a lot of different industries responding to it. The tech and AI industry has responded with plug-ins such as Trusted News, B.S Detector, Surf-Safe, and many other browser add-ons which will alert you to the trustworthiness of a news source. Some of these add-ons use Politifact, Snopes.com, and other statistic sharing sites to measure the fakeness. Others will flag the news source if it is satirical or possibly fake, but may accidentally flag art or feel-good news stories, or just offers you the chance to alert the programmers to fact-check the source. The journalism field itself has responded by urging their readers to trust only their sources, to use these plug-ins, or have created subheadings on their websites like the BBC to educate their readers on what they should be looking for, giving advice such as ‘does this seem trustworthy to you?’. The academic response has been in institutions such as Reuters and Stanford, who are working to create large databases of fake news, and creating large quantities of data on how these are written and distributed.

Our intervention is to use a combination of both contemporary media and academic sources–like those being offered by the institutions above–to use these databases to help inform the consumer of the lexical demarkers of fake news, so that we can both educate and empower the readers.

Image 2, 3, 4: SurfSafe Plug-in, Trusted News, Fake News Detector.

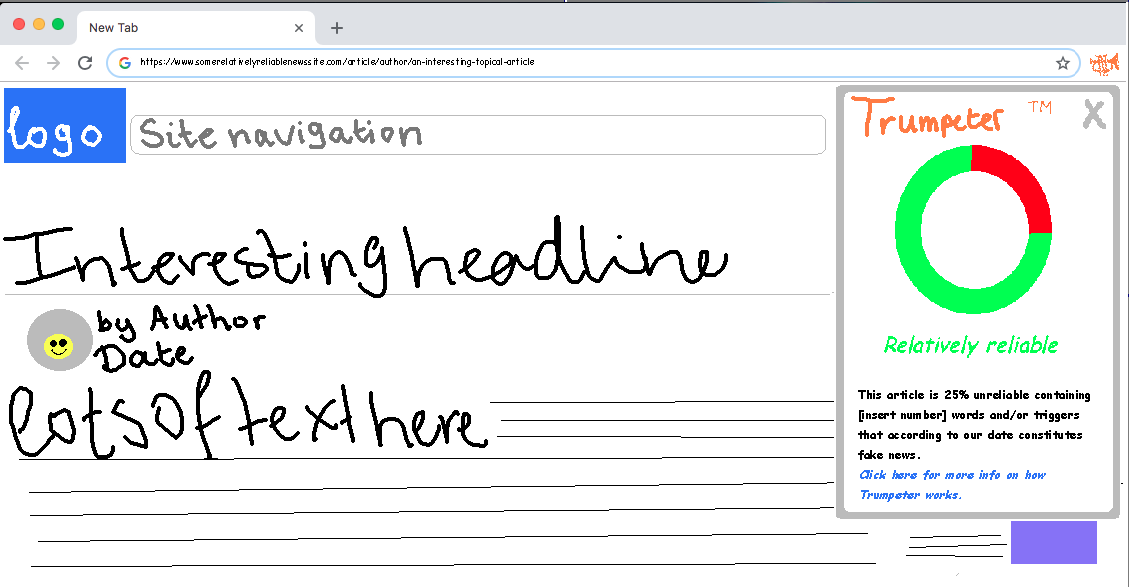

Trumpeter

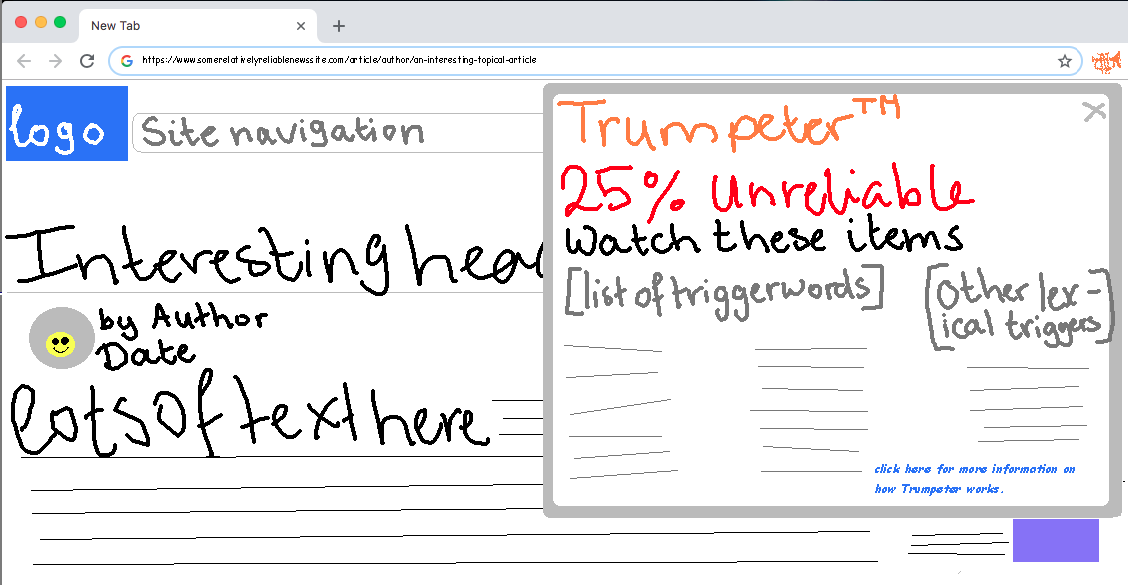

Our application, Trumpeter, is a browser add-on which can be used to scan articles and news sources on news sites or social media streams on their reliability based on linguistic elements present in the text. If a user opens the Trumpeter plug-in window, the simple view will pop up. The simple view of Trumpeter shows the user the reliability of the article on a scale of 0-100%. The user can click through to the detailed view, which flags the linguistic elements that cause the reliability rating to go down. Both windows include a hyperlink to the Trumpeter website which thoroughly explains the algorithms behind Trumpeter. A user can choose to show or hide this window, making Trumpeter a non-invasive plug-in, giving users the option to browse their favourite click-baity entertainment websites without being notified of the potential fakeness of it all.

Image 5: Demo of the simple view of Trumpeter when used on an article.

How does it work?

The output of the plug-in appears to be a standard across many fake news, tracker, or cookie related browser plug-ins; to establish whether or not the article is fake news and alert the user to its status. However, our plug-in is designed not to simply highlight or flag something as fake news like other add-ons, as you can see from our above examples that these do not react for example to content created by news sources simply designed for entertainment or opinion, but to equip the user with what can be misleading or inflammatory about a piece using lexical diameters. Other fake-news plug-ins focus on IP addresses, photos, videos with text, pop-ups etc, flagging an item for such based on coding or visual clues. Our plug-in uses lexical algorithms to scan the articles based on fake news databases, and then highlights them for the user. Using a combination of web scraping, and a lexical algorithm which we will feed our database of words used most frequently in fake news articles, sourced from institutions like Reuters and Stanford Media Lab, we will not only be able to stay up to date with how media and fake news is evolving, but equip our users with their own tools to also register this problem in their own consumption of media.

Image 6: Demo of the detailed view of Trumpeter when used on an article.

Our List

Our list was compiled using research we had found looking at open source content provided by Reuters and Stanford, as well as studies done by the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, Birmingham University, MIT, and the Paul G. Allen School of Computer Science & Engineering University of Washington. While the entire databases were not accessible, we were able to compile a workable list from the papers that they published. Markers such a hyper sensationalist words (Attack, Benghazi, Bleak, Damned, Destroy, Endless, Eviscerate), over use of these words, spelling, grammar, and over used punctuation (!!), were compiled and then cross referenced with news articles published on or immediately following the day of the speech President Donald Trump made apologising to alleged sexual assault perpetrator Brett Kavanaugh, as we had the text of the actual speech given and had full audio visual clips of the news event to cross-reference to prove the legitimacy of what reported and quoted to further split hairs when understanding whether or not articles were legitimate or truthful.

Demo

To establish the groundwork for the plug-in to work, we ran a manual demonstration without the fully established or coded software necessary for a successfully implemented intervention such as Trumpeter to succeed as an internet browser plug-in. With the example of Trump apologising to the now-Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh in mind, we found articles from the day of the incident or (8th October 2018) the day immediately after (9th October 2018) from some of the news sources as established by a public American poll for most trustworthy news sites and also to some degree a list of trusted sites. The sites and articles we established as most pertinent to our demo were The BBC, Breitbart, Buzzfeed News, The Guardian, InfoWars, Reuters, and finally, to establish if it would work for smaller social media posts we also included a post by OccupyDemocrats Facebook page on the topic.

Image 7: The meme format somewhat defies the software due to its limitations, including image posts which at present cannot be recognised as easily as more raw text. Source: OccupyDemocrats Facebook page.

By manually listing every word in an Excel sheet and cross-referencing each article with the established list of words as mentioned above, we scored the six sites/sources with a concise and simplified one point per word system. Once finished, each sites’ scores were added to create their respective total. With our total scores lined out, we established that our linguistic tracking approach revealed many ‘trustworthy’ news sites along with feel-good stories scored much higher than average including The Guardian at 17 points and Buzzfeed News at 23 points garnering the two highest scores. The OccupyDemocrats Facebook page scored unreasonably low (3 points) comparatively which we can infer is from the lack of ‘incriminating’ words, with the short and snappy meme format defying the linguistic tracking. The two sites that scored in the middle however (10-19 points), with Breitbart at 14 points and InfoWars at 12 points, upon a further and more qualitative and critical approach given our understanding of the way fake news actually operates seem to be the most likely to post fake news. Therefore, given the depth of our studies on this it appears that a potentially flag worthy score may be in the middle of the range. This is likely due to 1, the prominence of many of the often emotive ‘flag’ words in articles that attempt to attract readers or to subscription via emotive or persuasive language, and 2, the relatively ‘slim-pickings’ in terms of available words to be linguistically analysed within the plug-in.

It needs to be said however, that while we did quantitative research by compiling as much as was available from the academic sources available, it is important to note that qualitatively this sadly at the present stage of development amounts to a drop in the ocean when there is an expansive library of research we could access with sufficient time and funding. This would be achieved through being established as a legitimate web browser plug-in. Therefore, by using the facilities and academic sources available to us from the library at the University of Amsterdam, we are legitimising our searches, yet we are unable to fully compound them due to the limited access at this moment in time. Hopefully however with further development we could reach out to these databases, or indeed news sites or news or information institutes leveraging any possible incentive for social media labs to outsource their findings to use or allow us access that furthers our development. With the presence of a fully implemented software there would be significantly faster, and therefore more readily available and analysable data, to establish common trends with articles of similar lengths and also similarities between all articles or sources. From there on we could even further finetune the scope of our definitions to the point where there is a fully comprehensive list of ‘flag’ words for each variety of content format predominant online. Further categorising content into categories could also contribute to furthering the scope and effectiveness of the app by being able to account for any potential nuances found within the content the app seeks to analyse.

The future of Trumpeter

Just as the other fake news plug-ins, Trumpeters has its limitations. For example, Trumpeter will only function in English, as our data sources are in English and we do not have similar resources in other languages. Another concern is the ever-changing nature of journalism and the internet. As fake news continues to be analysed, fake news writers will find new methods to write convincing fake news. This means we must remain up to date on said developments.

Currently, Trumpeter is proposed as a free add-on. Since it will continue to grow and need continuous updating to remain accurate, we will need to monetize it somehow. This can be in the form of paid versions of the plug-in, however the added features are still to be discussed.

The potential of Trumpeter for one includes the growth of the plug-in with time to develop more complex algorithms to encompass not only traditional news articles or the standard format for news information online such as news sites or messaging or social boards. This could include formats such as memes and social media posts that base their style off of a more light and conversational tone.

Trumpeter aims to not only to help people get to the truth, but it also aims to make the internet great again.

References

Keith, Tamara. “President Trump’s Description of What’s ‘Fake’ Is Expanding.” NPR, NPR, 2 Sept. 2018, www.npr.org/2018/09/02/643761979/president-trumps-description-of-whats-fake-is-expanding?t=1540323237329.

Meyer, Robinson. “The Grim Conclusions of the Largest-Ever Study of Fake News.” The Atlantic, Atlantic Media Company, 12 Mar. 2018, www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2018/03/largest-study-ever-fake-news-mit-twitter/555104/.

Vincent, James. “Browser Plug-Ins That Spot Fake News Show the Difficulty of Tackling the ‘Information Apocalypse.’” The Verge, The Verge, 23 Aug. 2018, www.theverge.com/2018/8/23/17383912/fake-news-browser-plug-ins-ai-information-