A Call for Collectivization: Addressing the atomization and exploitation of ‘lean platform’ workers

Sketching the Problem: Lean Platforms and ‘Precarity by Design’

The platform labor economy, epitomized by platforms such as Uber and TaskRabbit, is actively reshaping the relationship between workers and the labor that they perform. Sometimes referred to as the ‘online gig economy’ or ‘sharing economy’, platform-mediated labor is a rapidly growing sector in the current labor markets of both the United States and Europe, and is gaining traction worldwide. The US Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates that there are 1.6 million active ‘electronically mediated workers’ which account for about 1% of the total US workforce. On a more global scale, it is estimated that over 70 million workers are registered to online labor platforms worldwide.

However, the business models of these platforms do not benefit the worker. In his book Platform Capitalism, Nick Srnicek provides an outline of how online labor platforms work to maximize extraction while keeping their own costs to a minimum. The focus of these companies is uninhibited growth and cost-efficiency. However, this comes at the expense of worker’s basic benefits and decent wages, resulting in a high turnover of workers (Farrell & Grieg 2). Since platform workers are legally designated as “independent contractors,” the companies have no responsibility to provide basic employee benefits (Srnicek 76). Workers are atomized and isolated from one another while the oversight practices of companies remain opaque, attributed to ‘the algorithm.’ They are encouraged to see each other as competitors rather than collaborators. All these elements characterize platforms’ ‘precarity by design’.

As Niels van Doorn points out, idea of precarious labor arrangements predates platforms. The gig or on-demand economies have been “historically constituted by class, racial, and gender inequalities,” particularly in terms of low-wage domestic or service work (van Doorn 900). However, what we see now is an expansion of this model into new areas of the economy, and a more widespread precarization of labor.

This spread of the gig-economy also strongly relates to the societal glorification of the idea of work and productivity, coined as ‘workism’. While it is unlikely that platform workers see what they do as their true calling, workism contributes to the willingness to tolerate the precarity and exploitative practices. In fact, seeking work at any cost is glorified as a kind of entrepreneurship, a triumph of the individual who seizes opportunities and remains productive even in the face of an increasingly unstable labor market. In today’s hyper-competitive and entrepreneurial society, platform labor normalizes these conditions by repackaging precarity as flexibility, individuality, and entrepreneurship. As Srnicek argues, “A tool of survival is being marketed as a tool of liberation” (78).

In the following we want to sketch a solution that provides the benefits and security of more stable employment while preserving the flexibility and independence that platform workers enjoy. A change in organization of platform capitalism should address atomisation by taking collectivity at its starting point. This aligns with calls for a more equal wealth distribution through collective ownership of the means of production in platforms. For example, Terranova argues that any solution countering the wealth extraction of platforms should include deprivatization and a new way of social distribution of wealth to commons (53). In his proposal for utilisation of network technology for a post-capitalist society, Paul Mason sketches the idea of a publicly owned infrastructure and points to the possibilities of workers owned cooperative enterprises (2015).

The historical success of cooperative enterprises make them a viable model for the reorganization of labor relations in the platform economy. Worker-owned cooperatives can offer an alternative model of social organization to address atomisation, precarity and wealth distribution.

In the following we explore how low-wage workers operating through lean platforms can be empowered by the reorganisation of these platforms to collectively owned workers cooperatives. In what way can we combine a rich history of experimentation with cooperative enterprises with automation by design?

In sketching this solution, we were inspired by several networks of thinkers and practitioners which are exploring the potentials of applying this model to the platform economy under the umbrella of ‘platform cooperativism,’ (Scholz and Schneider).

The Workers’ Cooperative: Empowerment by Design

The central concept of a cooperative is that it is owned and governed by its workers who considered members of the cooperative. The members decide how profit is distributed and are collectively responsible for the oversight or management of the enterprise using democratic practices. A cooperative purpose is thus radically different from profit maximization and growth for a few as it works in the interest of all members.

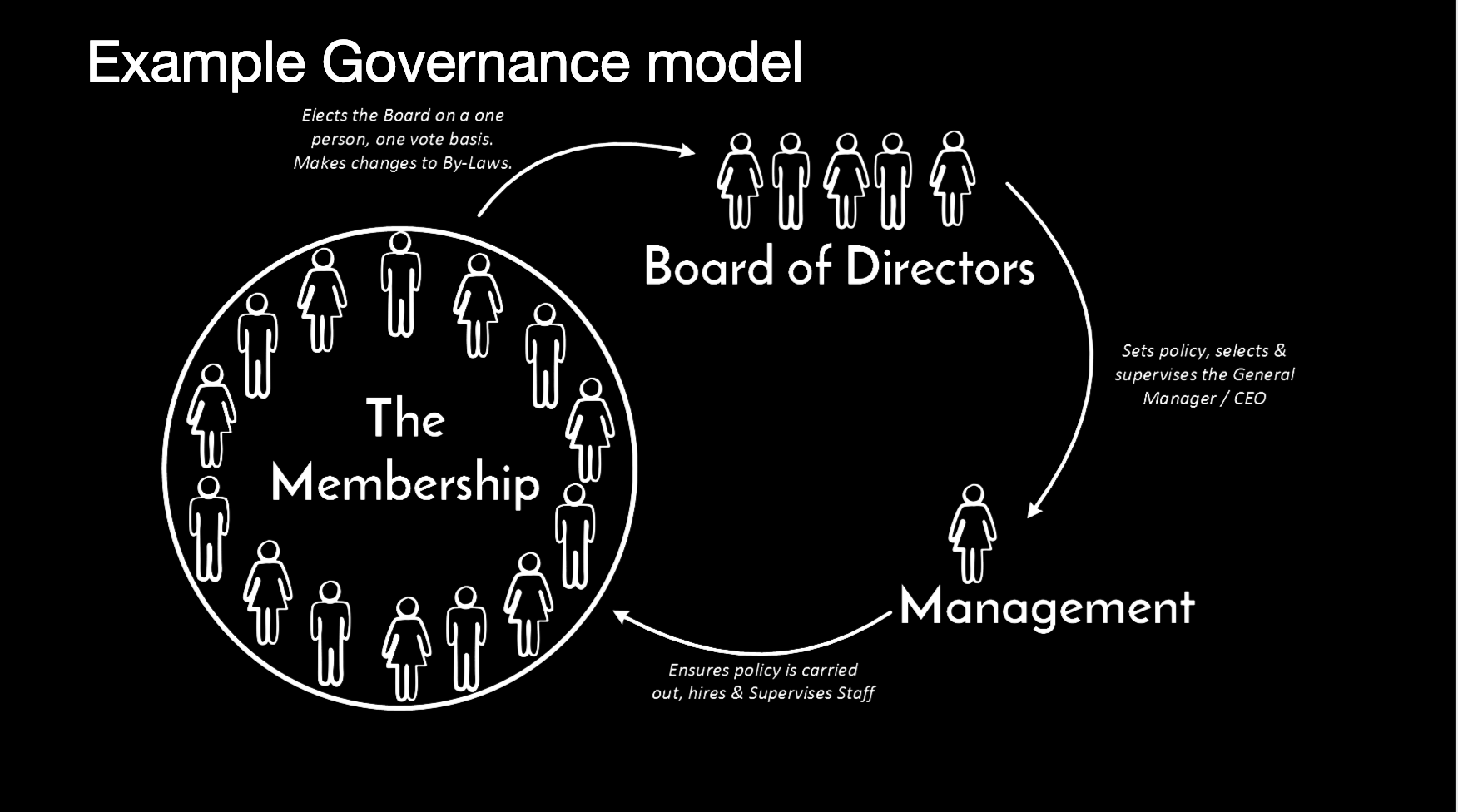

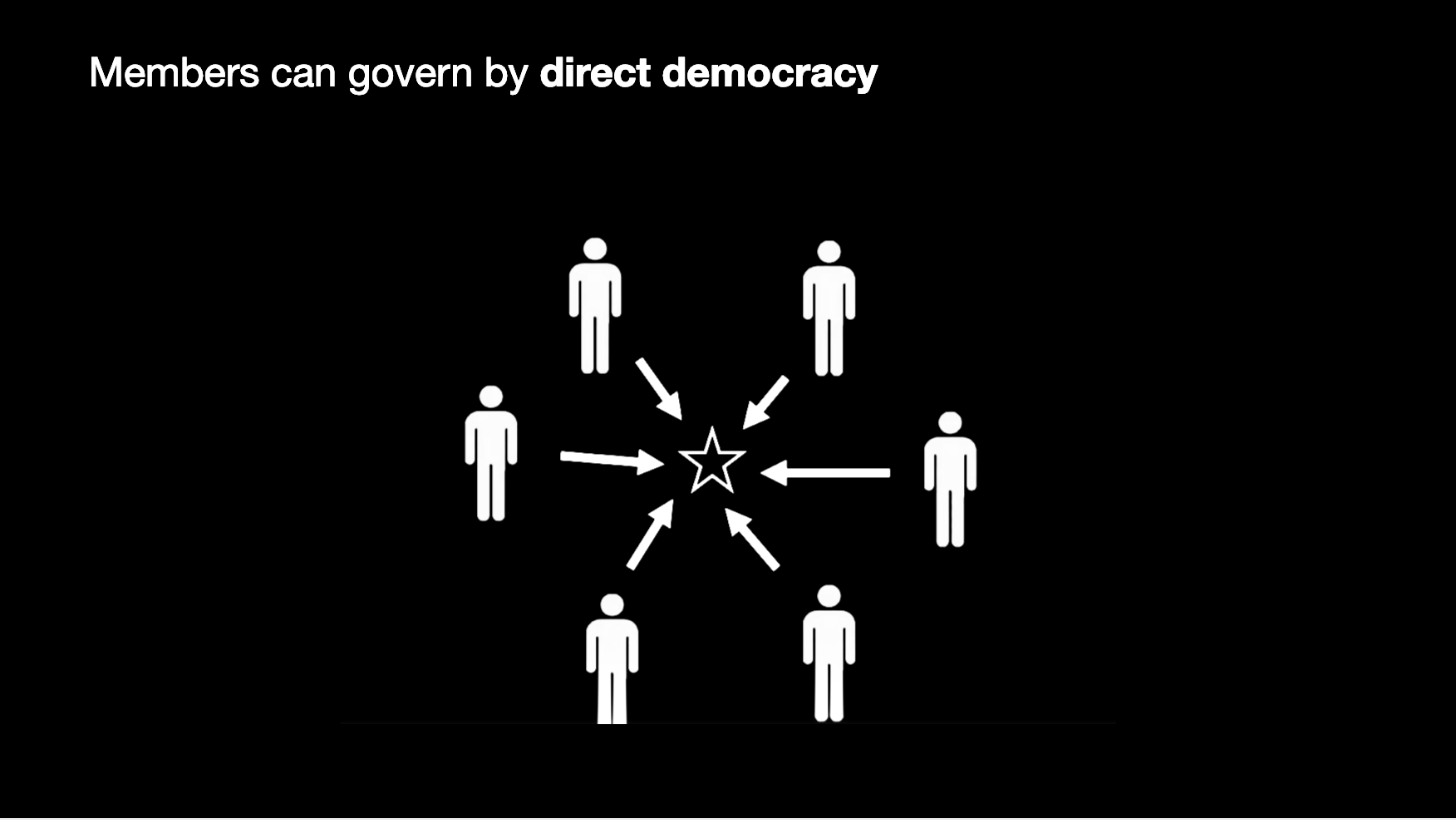

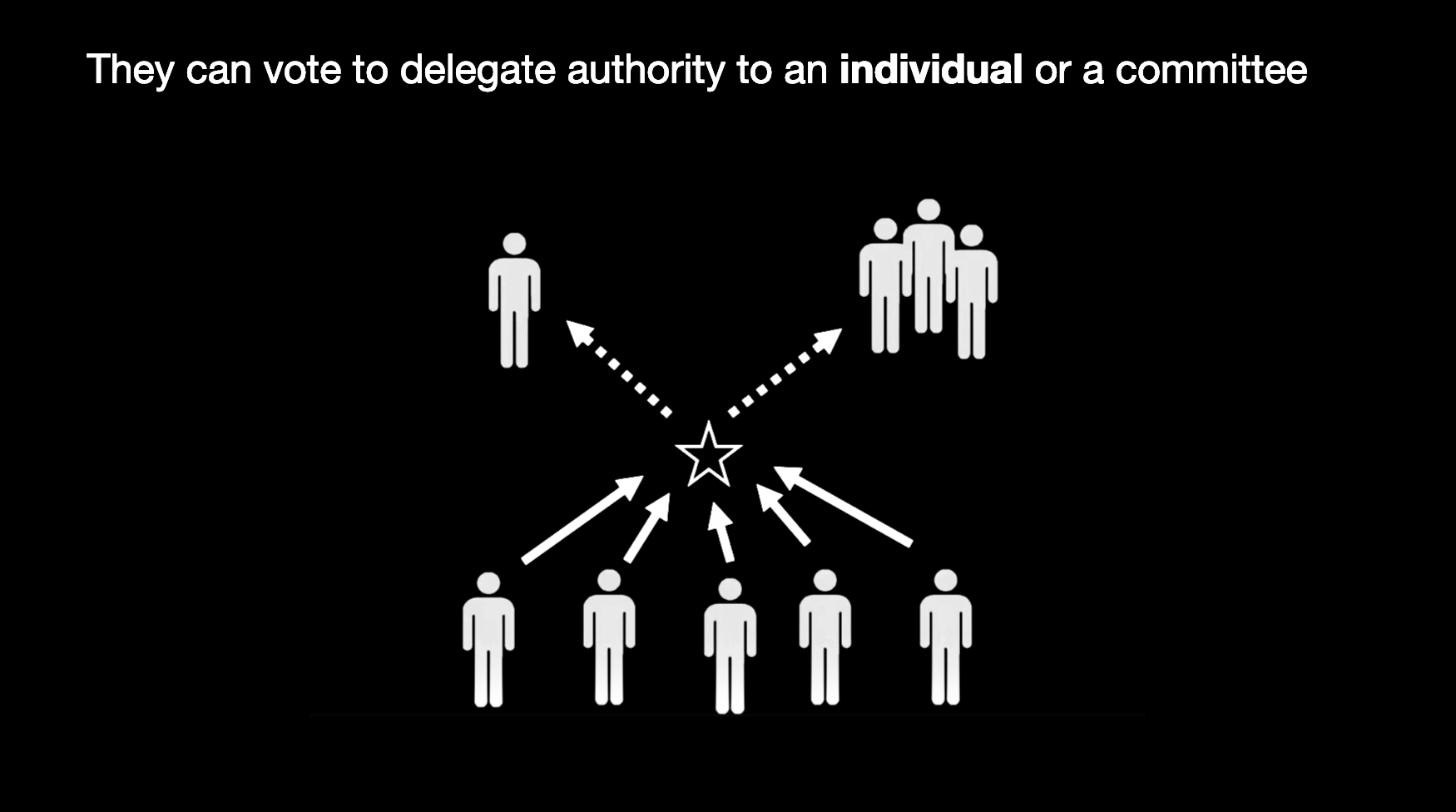

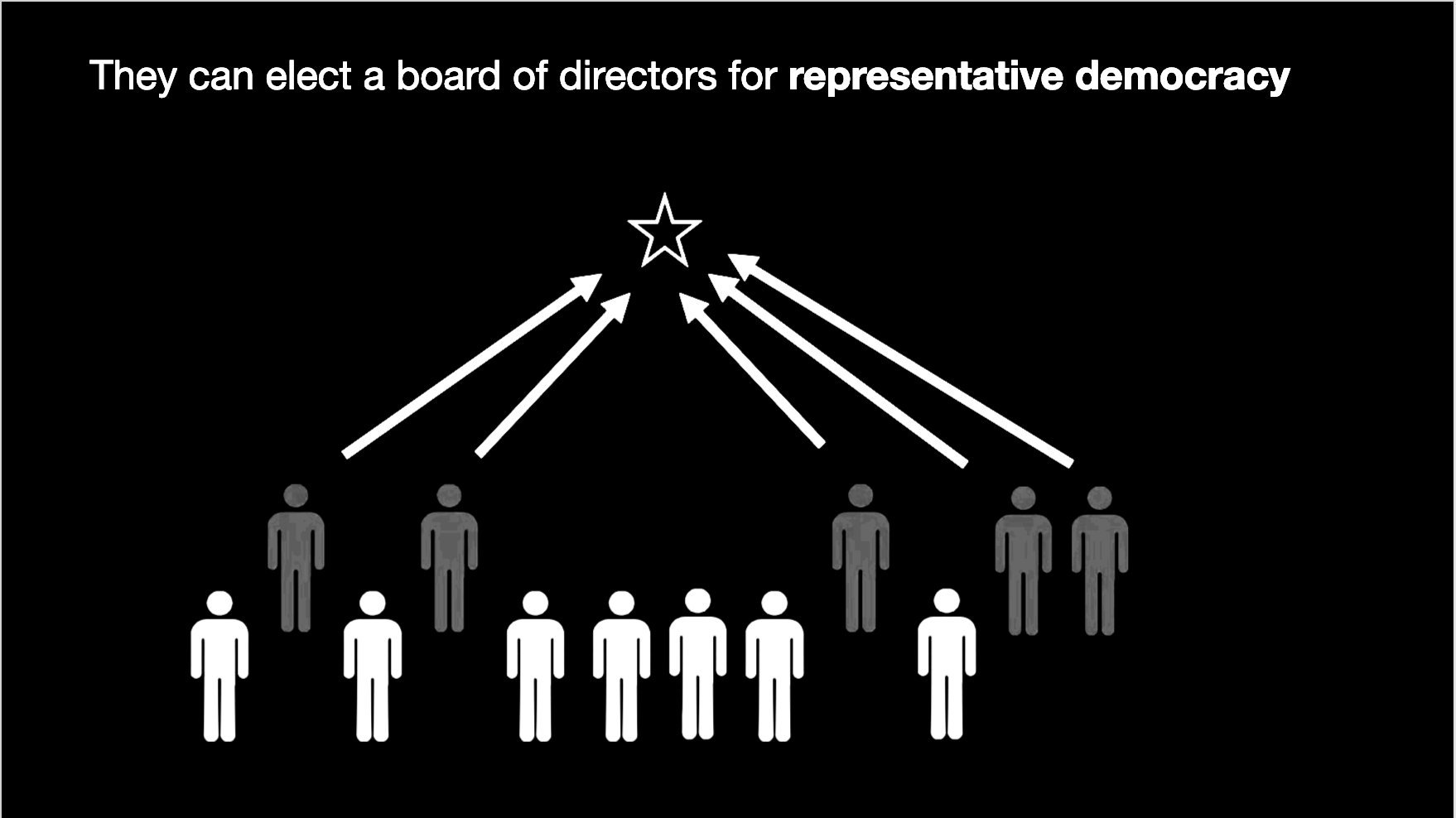

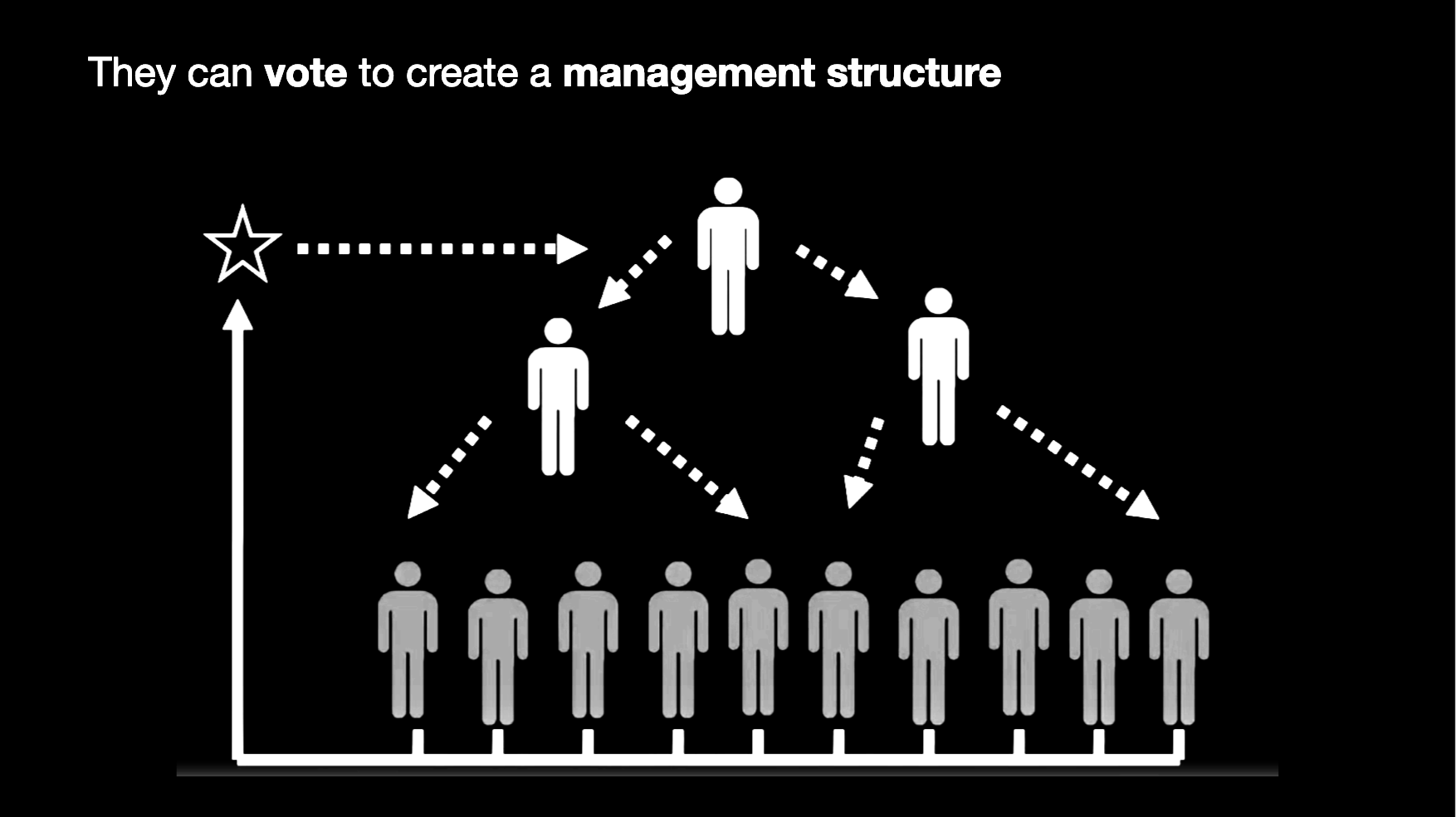

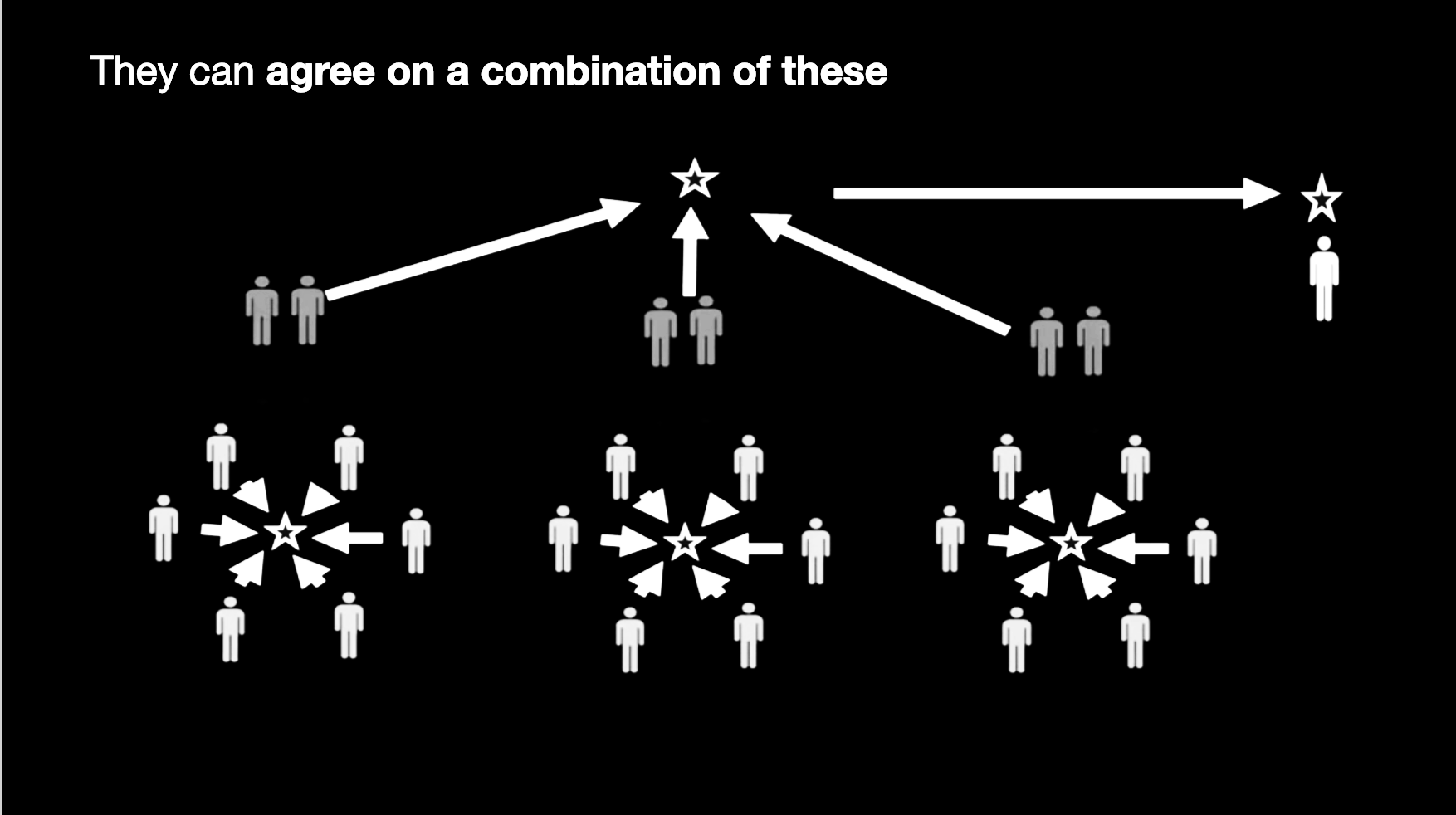

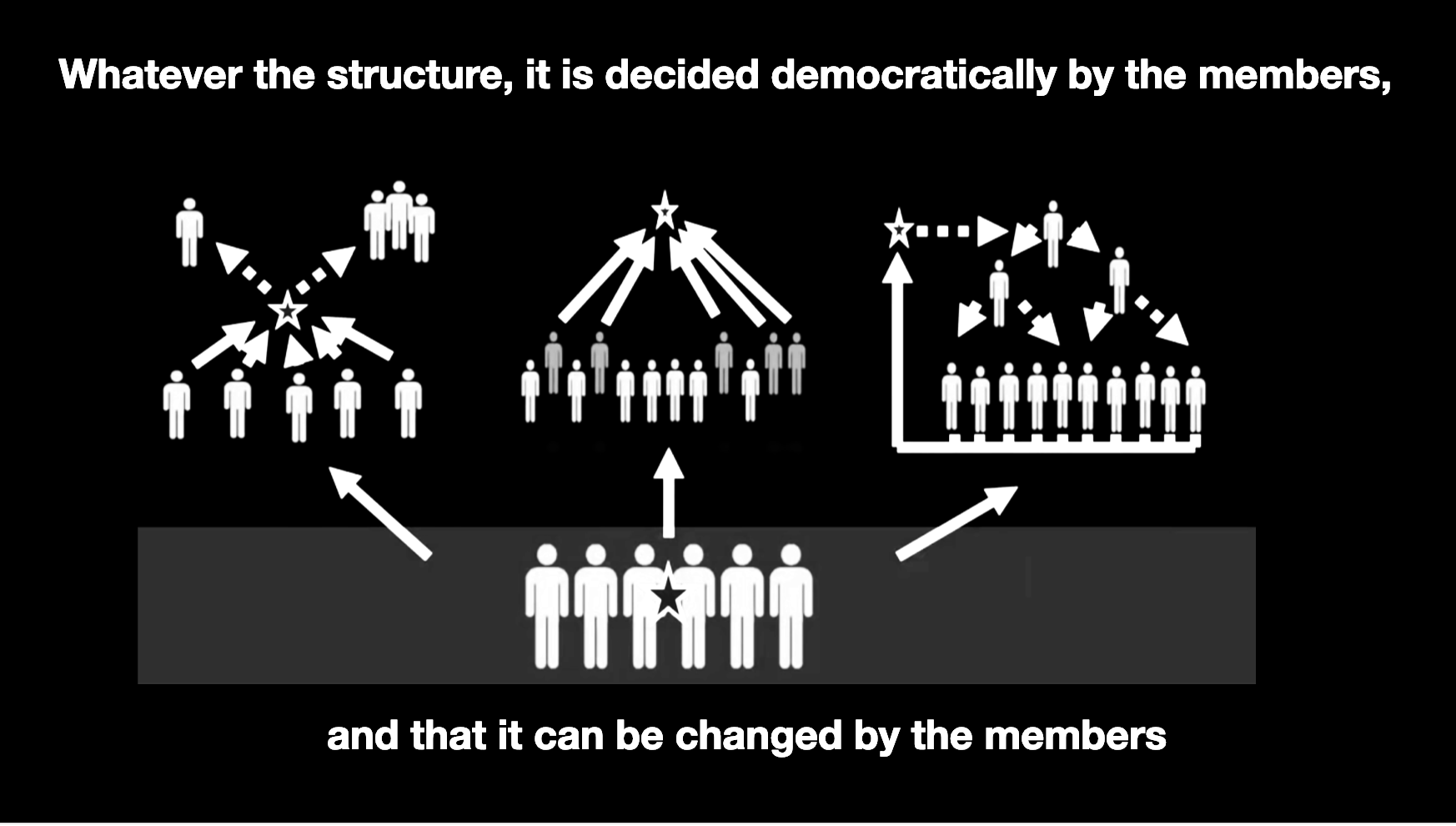

As for the governance model, a starting point is ‘one worker one vote.’ From there, members may choose different modes of representation for a more practical management of everyday business. This could include the creation of an oversight or management structure, but the key distinction is that such decisions are made democratically, and the power in making these decisions is distributed equally across the collective.

The following images offer examples of possible governance models:

The shared responsibility of members for the governance of the enterprise counters the isolation of the workers inherent in platform labor in respect to each other and the enterprise. But it also offers possibilities for the enterprise to connect to issues relevant for its local context. The cooperative is not at all a ‘one size fits all’ solution or rigid organizational template. Cooperatives can be, and are, organised in various ways-a cooperative creates its own mechanisms to make the decisions that affect the functioning and governance of the enterprise. This also mean they can be more lean and flexible in a far more substantial way than is now understood with the term, and can be adaptive to local needs. For example, in Amsterdam, curbing carbon emissions could be part of the ambitions of a cooperative. In Delhi, offering a safe space for women in face of the sexual harassment in transport might be a priority. This embeds the cooperative in its local community and the local issues at hand, instead of isolating the enterprise from its geographical and social context.

Due to its rich history in practise and experimentation, the cooperative model goes beyond mere theoretical speculation. Lessons learned from cooperatives can be extrapolated for its operationalization in a platform economy. Virginie Pérotin dissected two decades’ worth of international data on employee-owned and managed cooperatives in the U.S., Latin America, and Europe and compared them with normal businesses. The results are promising. Enterprises organised as cooperatives lead to an increased sense of ownership and commitment, better working conditions, and higher wages for typically low-wage work. Furthermore, cooperatives increase household wealth for low-income workers, leading to sustained demand. Unlike the current platform economy, staff turnover is significantly lower. According to Pérotin, cooperative business models are more sustainable: cooperatives are highly resilient to economic shocks and tend to survive 29% longer. They also have a higher productivity and weather recessions more effectively (Pérotin).

Though existing infrastructure, knowledge and experience is beneficial for the potential of a platform cooperative model, there are many challenges to addressed as well. For one, running cooperatives is high maintenance for its members. For its democratic governance model to work, managing proposals, solving differences and conflicts, coming to working agreements, requires the full participation of the workers in the process. The sometimes extensive bureaucratic framework or endless meetings can be tiring for members.

For such governance processes, there might be valuable insight to be gained in looking into the innovations of application and information design. For a platform cooperative to be truly at the service of its members, we would like to argue that it’s app cannot do without a user friendly, clear and comprehensible interface, designed with the same technological sophistication that offers users so of the largest platforms the convenience they enjoy.

Theorizing the Interface

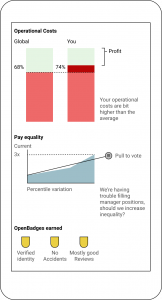

We propose to make a visual interface wherein the cooperative and its governance is materialized and made comprehensible on user friendly way, integrating the latest insights from UX design. The function of the interface is twofold. First, it will operationalize the governance processes in a streamlined, tangible way. Through this governance interface, proposals, discussions, decisions, voting are made as easy and clear as possible without sacrificing space for discussion and debate. The second function of the interface is to offer more transparency in data and performance metrics of the cooperative. This performance interface gives and every member equal access to how the cooperative is doing.

Performance Interface

The design of this interface is in itself again decided by its members. There is a collaborative design process to decide how the interface should look like, which performance metrics should be included, and how the feedback should be visualised and offered to the cooperative members. This could be considered a kind of ‘second order cybernetics’ in which the cybernetic process of determining the feedback mechanisms of the cybernetic organism.

Performance and Governance Interface

For complete transparency, all aspects of the cooperatives are included in some form in the interface, whether that be new management protocols or new hires. There can be no abstractions without a visual representation.

Including a user friendly, clear interface which streamlines governance processes and offers insight in the cooperative performance can balance trust and accountability in a group of people, and trust in technology, and bring back a visual concrete feedback of the abstract idea of solidarity.

Besides a clear interface, possibilities on a more protological, infrastructural level can be leveraged to improve cooperative processes. While no single technology can ensure complete trust in a process, there are tools to improve processes of vetting and control. And efforts to prevent abuse can be supported by inscribing checks into technology, such as with smart contracts.

By bringing in a user friendly interface we seek to alleviate the tedious bureaucracy involved in organizational governance. There will be no dry ‘quarterly report’ – the whole organization is a live, ongoing ‘report’ in constant flux.

Platform cooperativism as outlined here, which includes experiences of the vast UX industries to design a sophisticated interface, is a viable solution to the exploitative precarity of lean platforms such as Uber. In Amsterdam, the first Amsterdam Agenda for the Digital City was launched on 1 March. Entitled ‘A digital city for everyone, from everyone’, the agenda aims to achieve a free, inclusive and creative digital city. The agenda has disappointingly little to say about economy or precarity. We challenge Amsterdam, as part of its new digital agenda, to curb the exploitative practices of platforms that promote ‘precarity by design.’ The city could make meaningful steps toward a more just and equitable digital economy by stimulating the development and implementation of platform cooperatives. A truly inclusive agenda should inspire values of collectivity and solidarity to counter the disillusionment of an atomized and hyper-competitive society.

References

Farrell, Diana, and Fiona Greig. The Online Platform Economy: Has Growth Peaked? JP Morgan Chase & Co. Institute, 2016, https://www.jpmorganchase.com/corporate/institute/document/jpmc-institute-online-platform-econ-brief.pdf.

Mason, Paul. PostCapitalism: A Guide to Our Future. Allen Lane, an imprint of Penguin Books, 2015.

Pérotin, Virginie (2017) What do we really know about workers‘ co–operatives? in Mainstreaming co-operation. Chapter DOI: https://doi.org/10.7765/9781526100993.00019.

Scholz, Trebor, and Nathan Schneider, editors. Ours to Hack and to Own: The Rise of Platform Cooperativism, a New Vision for the Future of Work and a Fairer Internet. OR Books, 2016.

Srnicek, Nick. Platform Capitalism. Polity, 2017.

Terranova, T. (2004). “Free Labour” in Network Culture: Politics for the Information Age. London: Pluto Press.

van Doorn, Niels. “Platform Labor: On the Gendered and Racialized Exploitation of Low-Income Service Work in the ‘on-Demand’ Economy.” Information, Communication & Society, vol. 20, no. 6, June 2017, pp. 898–914. Crossref, doi:10.1080/1369118X.2017.1294194.