A.I. Influencers: Preaching to the Choir?

As virtual influencers are gaining popularity on social media platforms such as Instagram, an increasing amount of money is being invested into the development of so-called A.I. influencers. Will such influencers cause a shift in the relationship between different users and platforms?

Lil Miquela in an Instagram post. Source: @lilmiquela|Instagram 2019.

The Rise of Virtual Influencers

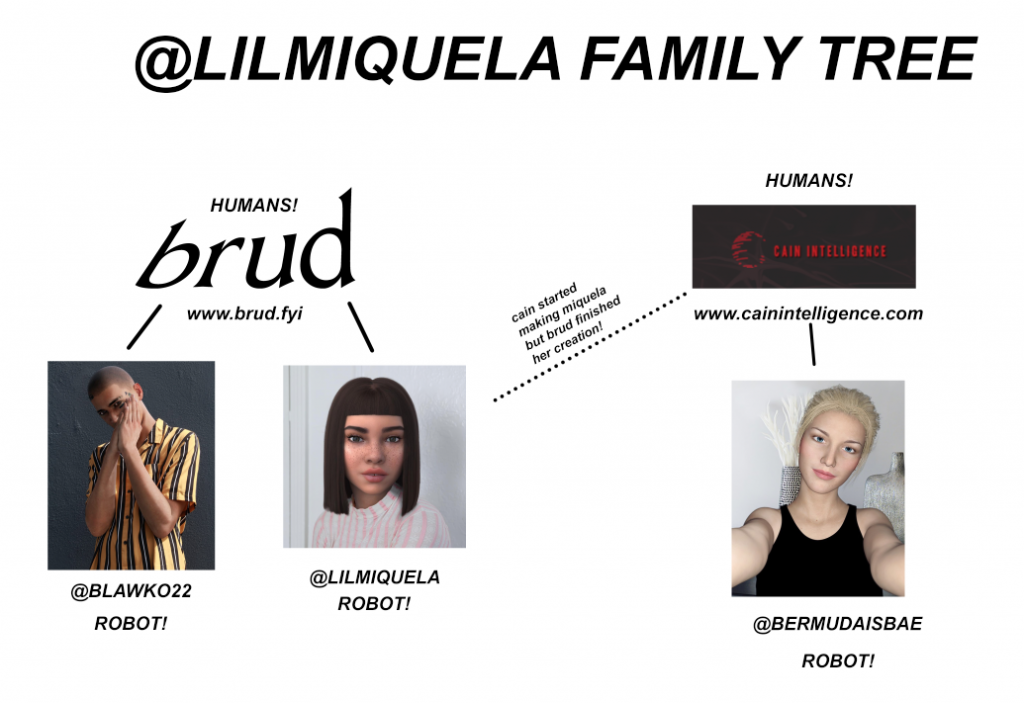

Meet Lil Miquela, a hip 19-year-old influencer, musician, model, and self-proclaimed queer and Black Lives Matter activist with 1,6 million followers on Instagram (@lilmiquela). There is only one thing that sets Miquela apart from other digital influencers on the platform: Miquela is a virtual being, created by Los Angeles-based media and technology company Brud (Tiffany).

Lil Miquela’s digital squad. Soure: Michael Ronaldo|Wikimedia Commons 2018.

Miquela is not the only virtual influencer present on social media platforms and she even forms “digital squads” with other characters such as Bermuda and Blawko, yet she is the most successful one (Hill; Alexander). This success hasn’t gone unnoticed and an increasing amount of money is being invested in the industry with companies like Betaworks Ventures and Sequoia Capital investing a total of 125 million dollars in Brud in 2018 (Shieber). These investments are set to put Artificial Intelligence (A.I.) technology behind virtual characters like Miquela — who are now being created by humans using motion graphics (Alexander). Through A.I. technologies Miquela will be able to communicate with her fans on a personal level and provide them with fashion advice (Groot). In January 2019, The Verge reported that the general director of Betaworks’ startup bootcamp, Danika Laszuk, sees a future in which virtual creators and all the content they post are completely computer-generated (Alexander).

Although the technology is not that far yet, it is interesting to examine how these A.I. influencers are different from human influencers and how their rise could increase the already powerful position of the platform representing themselves on.

Platforms as Multi-Sided Markets

The concept of the multi-sided market originated within economy studies, but has been widely applied in the fields of media and computer science (Rieder & Sire 199). New Media, Information and Communication scholars Bernhard Rieder & Guillaume Sire describe a multi-sided market as “a platform that brings together at least two distinct groups of end-users” (199). By bringing the groups of end-users together, the platform enables those groups to interact, while profiting from them through the collection of data and selling advertisements (Rieder & Sire 199–200). Instagram for example enables interactions between users and advertisers as it squeezes advertisements into user’s feeds. Although Instagram doesn’t have a monetization programme like YouTube, where content creators can earn money through the number of views they receive on a video (Van Es 1), the platform does allow individual users to advertise through their personal accounts.

Influencers and the Algorithmic Power of Platforms

A Platform’s affordance to advertise through personal content creation, has led to a rise of digital influencers. Influencer marketing is a form of marketing which revolves around the idea that individuals can impact the beliefs and practices of followers through an intimate relationship (Cotter 896–897). These influencers basically make money identifying with brands recommending specific products on their personal accounts (Marwick 138). In the case of virtual influencers like Miquela, major fashion brands like Prada and Calvin Klein pay Brud to have her appear in their clothes (Yotka; Calvin Klein).

Lil Miquela in an Instagram post tagging Prada. Source: @lilmiquela|Instagram 2018.

Lil Miquela kissing Bella Hadid in a YouTube video for Calvin Klein.

Source: Calvin Klein|YouTube 2019.

In order to continue this practice of self-commodification, influencers depend on feedback from their audience (Cotter 897). It is the platform that provides them this feedback through data representing engagement such as likes, comments and followers. At the same time, this data represents the input that the platform’s algorithm uses to determine the visibility of its users and content. In principle, the more engagement around a certain piece of content, the more likely it will be that this content will be shown to other users, increasing engagement for that user-post or hashtag. This creates popularity loops that is driving influencers to engagement-focused behaviour, that makes them more likely to be featured by the platform’s ranking algorithm (Bucher 11; Carah 387). Because of the way these platforms are set up, a lot of power lies with algorithm that decides what gets prioritized in user feeds (Gillespie 165).

More Power to Platforms with A.I. Influencers

For the past decade, more and more technology companies are investing in the development of A.I. technologies that are expected to perform tasks “associated with some level of human intelligence” (Guzman & Lewis 3). Within the field of communication, some of these technologies are designed to respond to their (human) communication partners while learning about them at the same time. By doing so, these technologies are able to adjust their interactions according to these processes (Guzman & Lewis 3–4). In the case of A.I. influencers, this would mean that they adjust their online content (e.g. posts, comments, direct messages) according to user-feedback on a platform. Although this seems similar to current influencer practices as explained above, there is a notable difference. The technology behind an artificial intelligent influencer will be programmed to follow popular content on a platform and adjust content towards this content in order to increase engagement. According to this logic, an A.I. influencer is compliant by design. Contemporary human influencers or the creators of virtual influencers like Miquela, can still generate high engagement rates with content that was initially not expected to be popular among their audiences based on previous data. Besides that, these influencers are arguably more likely to be affected by the ways in which they have to adapt their behaviour in order to stay visible on the platform then artificial intelligent ones. The compliant nature of A.I. influencers may cause them to follow a platform and its attempts to increase engagement uncritically. It is for this reason that a rise of such influencers can increase the already powerful position of the platform ranking algorithm as an arbiter.

The Risk of Sidelining Oneself

With the development of A.I. influencers, companies like Brud also take a risk to sideline themselves in the influencer business. As explained above, platforms profit from their users through the collection of data they generate (Rieder & Sire 199–200). It is this data that provides the A.I. influencers the feedback they need in order to continue to develop their interactions with users (Guzman & Lewis 3–4). This brings me to the idea that a platform could also start to create A.I. influencers themselves using the data they collect. By doing so, it becomes possible for the platform to take over the position of the companies behind the A.I. influencers and profit from that. Although this idea is rather speculative, it does raise questions regarding the entities we will interact with on social media platforms in the future. How will we relate to them? And how will they influence the way we experience our relationships?

References

@lilmequela. “Go off!! #pradagifs are live in stories! Start posting and tag me 😈#PradaFW18 #MFW.” Instagram. February 22 2018. September 20 2019. <https://www.instagram.com/p/BfgDCGqFitF/?utm_source=ig_embed>.

@lilmequela. “Sound healing was nice but let’s face it ~ nothing makes me feel better than a fashion party 🗽📸 Thanks to @gucci x @iammarkronson for cheering me up 🤖💕 #NYFW.” Instagram. September 12 2019. September 20 2019. <https://www.instagram.com/p/B2TKkm9HGwh/>.

Alexander, Julia. “Virtual creators aren’t AI — but AI is coming for them.” The Verge. 2019. Vox Media. January 30 2019. September 10 <https://www.theverge.com/2019/1/30/18200509/ai-virtual-creators-lil-miquela-instagram-artificial-intelligence>.

Bucher, Taina. “Want to be on top? Algorithmic Power and the threat of invisibility on Facebook.” New Media & Society 14.7 (2012): 1164–1180.

Calvin Klein. “Bella Hadid and Lil Miquela Get Surreal|CALVIN KLEIN.” YouTube. May 16 2019. September 12 2019.<https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h2jdb3o2UtE>.

Carrah, Nicholas. “Algorithmic brands: A decade of brand experiments with mobile and social media.” New Media & Society 19.3 (2017): 384–400.

Cotter, Kelley. “Playing the visibility game: How digital influencers and algorithms negotiate influence on Instagram.” New Media & Society 21.4 (2019): 895–913.

Gillespie, Tarleton. “The relevance of algorithms.” Media Technologies. Eds. Gillespie T; Boczkowski P.J. and Foot K.A. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2014. 167–194.

Guzman, Andrea L. & Seth C. Lewis. “Artificial intelligence and communication: A Human–Machine Communication research agenda.” New Media & Society 00.0 (2019): 1–17.

Hill, Harry. “Here’s what you need to know about those CGI influencers invading your feed.” Mashable. 2019. Mashable Inc. May 07 2019. September 15 2019. <https://mashable.com/article/cgi-influencers-instagram-what-you-need-to-know/?europe=true>.

Marwick, Alice. “Instafame: luxury selfies in the attention economy.” Public Culture 27.75 (2015): 137–160.

Rieder, Bernard & Guillaume Sire. “Conflicts of interest and incentives to bias: A microeconomic critique of Google’s tangled position on the Web.” New Media & Society 16.2 (2014): 195–211.

Shieber, Jonathan. “More investors are betting on virtual influencers like Lil Miquela.” Tech Crunch. 2019. Verizon Media. January 14 2019. September 15 2019. <https://techcrunch.com/2019/01/14/more-investors-are-betting-on-virtual-influencers-like-lil-miquela/>.

Tiffany, Kaitlyn. “Lil Miquela and the virtual influencer hype, explained.” Vox. 2019. Vox Media. June 03 2019. September 15 2019. <https://www.vox.com/the-goods/2019/6/3/18647626/instagram-virtual-influencers-lil-miquela-ai-startups>.

Van Es, Karin. “YouTube’s Operational Logic: “The View” as Pervasive Category.” Television & New Media 00.0 (2019): 1–17.

Yotka, Steff. “Prada Launches Instagram GIFs With Help From a Fictional It Girl.” Vogue. 2018. CN Fashion & Beauty. February 22 2018. September 20 2019. <https://www.vogue.com/article/prada-instagram-gifs-lil-miquela>.