About to Lose Your Sh*t? There’s an App for That!

We’ve all been there: an annoying boss, a roommate who never cleans up after themselves, a sibling who “borrows” your things. But, imagine, right in the heat of things, you reach into your pocket, swipe left a few times, and, just like that, you’ve hugged and made-up. This might sound like a touchy-feely utopia, but with the help of Dr. Peter Coleman and Robert Ferguson’s Making Conflict Work (MCW) app it’s a possible reality.

The Quest for Calm

The role of a mediator, as an objective third party, is often used as a holistic alternative to the legal system (Government of Canada). Many argue that offline systems of conflict resolution can’t develop fast enough to effectively translate into the digital space (Katsh et al. 53). The MCW app, however,has emerged as a new approach to conflict resolution that translates the offline tactic of mediation into a completely automated digital form. As of 2019, the MCW app is the only application on the market attempting this form of digital automated mediation. Other mediation applications on the market still include the role of human mediators. For instance, Mediate to Go connects users to offline mediators and PEACEGATE connects users to mediators through live chat (International Mediation Institute).

Capturing the Elusive ‘Win-Win’ Scenario

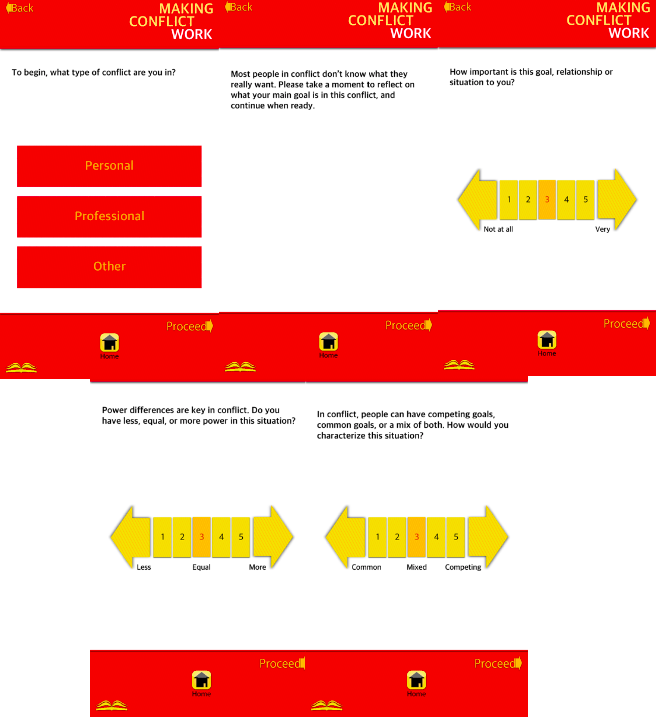

The MCW app’s goal is to create a “win-win scenario” where all parties “win” the conflict (Coleman). To accomplish this, MCW asks users a series of five questions, to be answered in the heat of any conflict. These steps can be seen in the following screenshots:

After completing this ranking process, one of seven scenarios (categorizing the user’s conflict) and potential solutions are presented: 1) Compassionate benevolence = pragmatic benevolence 2) Command and control = constructive dominance 3) Partnership = collaboration 4) Enemy territory = competition 5) Cooperative dependence = cultivated support 6) Unhappy tolerance = strategic appeasement 7) Independence = selective autonomy (Coleman and Ferguson).

Can an App Deal with All the Feels?

“Conflict is a lot like fire. When it sparks, it can intensify, spread, and lead to pain, loss, and irreparable damage.”

(Coleman and Ferguson, Making Conflict Work 1).

Sure, the MCW app offers some good pointers on conflict resolution but can an app truly help resolve such emotional scenarios? Those who believe in the theory of “technological singularity”, as talked about in Dr. Shanahan’s book The Technological Singularity, believe that there is a future where technological growth is able to progress beyond the point of human abilities – including emotionally. In more recent years, there has been an increase in apps designed to aid human mental health struggles – offering an example of this potential future (Kretzschmar et al. 1). From this perspective, it would seem an effectual mediating app could resolve even the most emotional conflict better than any offline human-based system.

Now before you frantically throw your iPhone across the room for fear of it outsmarting you, let me offer two main points of debate that the MCW app presents.

A Strict Binary: Is It True or False?

The MCW app offers a very simple, and fixed, pathway for solving conflict that offers a strict binary about humans: conflicts are between two people, our lives are primarily divided into personal and professional, there is power and no power, and there is care and don’t care. It is not surprising that the conflict resolution technique originally explained in the Making Conflict Work book was turned into a binary narrative within the app format. Afterall, the mathematical foundation of computers are entirely based on true or false statements, the basis of binary code (Wolfram).

However, a binary way of thinking is also at the route of most conflicts. Even the MCW website explains that humans often get “stuck in one or two chronic ways of responding to conflicts at work and in our personal lives” (MCW). The role of an offline mediator is much more nuanced than a binary position and involves ongoing discussions with all involved parties and unique solutions for each scenario (Government of Canada). Is the MCW not contradicting the role of the mediator through its binary form or does this pre-determined path create even more objectivity?

Is App Objectivity Possible?

This question raises another important debate – the overall objectivity of the MCW app. The role of an offline mediator is to be objective (Government of Canada). However, you can easily question the objectivity of apps. In Dr. Noble’s 2018 book Algorithms of Oppression, she illustrates how search engines, although perceived as objective, contain biases based on both the values of their creators and the broader social content that the creators are a part of (Noble). As well, Dr. Noble illustrates how this subjectivity most commonly is skewed against the social systems’ minorities.

This concept of subjective technologies can be expanded to the MCW app. To name a few of the creators’ inherent subjective lenses: they are both middle-aged white men who approach the topic of conflict from an American perspective, with a higher educational background (MCW). Within the society they exist, these subjectivities create a level of racial, social, and economic privilege. However, one could argue that offline, mediators would hold the same subjective biases and that a mediator is never fully objective. If objectivity is never fully attainable, does it even matter that the application has inherent subjectivity?

Will Good Intentions Produce Effective Technology?

Many applications, including the MCW app, are marketed as solving, or at least making easier, human issues. Dr. Marwick’s academic work brings attention to the active, and conscious, role of Silicon Valley in promoting a set of values that ultimately claim new technologies present “universal solutions to localized problems” (Marwick 317). However, as Marwick shows, these are a set of values created to ultimately financially benefit the technology industry.

However, when it comes to the MCW application, it was not created by a huge Silicon Valley corporation. This app was built by two mediators who do not have a technological background and, I would argue, primary intentions to aid those in conflict. However, the translation of their personal skills as mediators does not as effectively come across within the MCW app due to its binary and subjective nature. In this case, I believe the role of the human mediator is still more effective than that of the application.

That being said, new mental health applications built on artificial intelligence offer a potential glimpse into the future of an app’s ability to process and respond to emotionally charged issues. If these advances are translated into the conflict resolution sector, we can expect to experience a much more advanced version of the MCW app: one that can keep a level head during an argument, handle your annoying boss, and even get your roommate to clean up after themselves.

Works Cited

Coleman, Peter T. and Robert Ferguson. MCW: Making Conflict Work. iPhone application. Apple App Store. 2015. http://www.makingconflictwork.com/app-iphone-android/. Accessed 13 September 2019.

Coleman, Peter T., and Robert Ferguson. Making Conflict Work: Harnessing the Power of Disagreement. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2014.

Coleman, Peter T. “How to Resolve Conflict With an App.” Psychology Today, 18 February 2016. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/the-five-percent/201602/how-resolve-conflict-app.

Fog, Rachel. “Problem Solving and Conflict Resolution: Real Time Talk.” Keeping-It-Real, 2 Feb. 2016, https://rfogblog.wordpress.com/2016/02/02/problem-solving-and-conflict-resolution-real-time-talk/.

International Mediation Institute. “Apps.” International Mediation Institute, https://www.imimediation.org/resources/online/apps/. Accessed 22 Sept. 2019.

MCW. “Home | Find a Conflict Resolution Strategy.” Making Conflict Work, http://www.makingconflictwork.com/. Accessed 20 Sept. 2019.

Government of Canada. “Role of the Mediator.” Government of Canada Federal Public Sector Labour Relations and Employment Board. https://www.fpslreb-crtespf.gc.ca/drs/role_mediator_e.asp. Accessed 14 September 2019.

Katsh, Ethan et al. “Is There an App for That? Electronic Health Records (EHRS) and a New Environment of Conflict Prevention and Resolution.” Law and Contemporary Problems 74(3), Summer 2011, pp. 31-56.

Kretzschmar, Kira et al. “Can Your Phone Be Your Therapist? Young People’s Ethical Perspectives on the Use of Fully Automated Conversational Agents (Chatbots) in Mental Health Support.” Biomedical Informatics Insights 11, 2019, pp. 1-9.

Marwick, Alice. “Silicon Valley and the Social Media Industry.” The SAGE Handbook of Social Media, SAGE Publications Ltd, 2018, pp. 314–28. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.4135/9781473984066.n18.

Noble, Safiya Umoja. Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism. New York University Press, 2018.

Shanahan, Murray. The Technological Singularity. The MIT Press, 2015.

Wolfram, Conrad. “Binary thinking – right for computers, wrong for the real world.” The Financial Times, 30 October 2015. https://www.ft.com/content/1327bc52-7eec-11e5-98fb-5a6d4728f74e.