HUMAN UBER: CHAMELEONMASK AND THE COMMODIFICATION OF THE BODY IN THE GIG ECONOMY

The year is 2030 and you want to visit your grandmother in a town halfway across the globe. FaceTime could help here, but you want something a little more physical. You pull out your phone, open ChameleonMask, and order a warm body to physically represent you to your grandmother. Through the combination of video conferencing and direct messaging, you instruct your ChameleonMask humanoid to go to your grandmother’s house, hug her, and talk to her from thousands of miles away. Pretty soon, this could be a reality.

THE HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF TELEPRESENCE

While the idea of ‘telepresence’ has its roots in fictional literature from as early as the 1940s (Minsky), the actual technology began development during the 1980s and 90s – a time when big business was booming. The original idea behind telepresence technology was to allow for businessmen (a highly gendered term yet accurate for the time) to conduct business from a variety of locations while still feeling sensorially present. What we now refer to as video conferencing was born out of theoretical and technological advances in the field of telepresence. Slater and Wilbur theorize the key components of virtual presence – inclusiveness (what is excluded from the user’s senses), extensiveness (how much sensation does the system provide the user), surrounding (how much is included in the user’s sight), and vividness (the quality of the video) – all of which are part of the ChameleonMask experience (Slater and Wilbur n.p.).

HOW WOULD IT WORK?

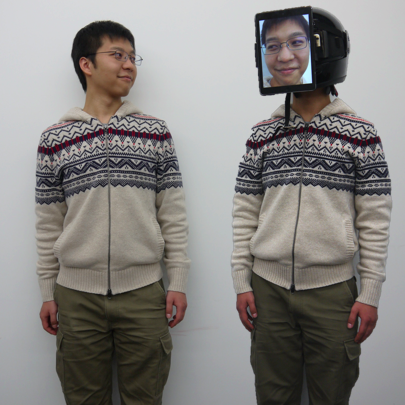

The idea is really quite simple. ChameleonMask – dubbed ‘Human Uber’ by Jun Rekimoto – allows users to hire a human “surrogate” that acts as the users’ physical body (Sujin). Outwardly, the surrogate is wearing a mask that has a tablet attached to it – presenting a digitally reconstructed, real-time video of the user via a video-calling service. Internally, the surrogate sees an interface where the user can command things like, “hug him” or “go to the bar and get a drink.” The technology, announced in 2018, is still under development at Rekimoto Lab, so the details of app interface, regulations, logistics, etc. have yet to be materialized.

PART HUMAN, PART MACHINE

ChameleonMask is a unique technological idea that represents a departure from other services like it – Uber, TaskRabbit, Rover, etc. – within the gig economy. This is because users would be renting the bodies of surrogates, not simply requesting a service [a ride] from a provider [an Uber driver]. As Hofmann discusses in her work on mediated democracy, “… technologies are understood as mediators of the relationship between people and the world. Hence, people and machines are not considered as separate entities but as mutually constituted… The human-machine bond shapes our common life together, our modes of social integration and communication” (Hofmann 5). With ChameleonMask, the body becomes a technology and the distinction between human and machine becomes even harder to distinguish than Hofmann suggests with this quote.

The fusing of human and technology in this way becomes particularly interesting when thinking about agency, identity, and technological capacity. Unlike Uber, where the driver can take a break or decide to stop working, surrogates function as physical manifestations of the user. When you are literally acting as someone else’s body, is it still your own? Do the desires of the user precede the agency of the surrogate?

Truly, surrogates for ChameleonMask could be boiled down to a muscle, organs, and flesh – a puppet with its strings being pulled by a remote user. In her work on the buying and selling of bodies, Nancy Sheper-Hughes states, “… in the larger society and in the global economy ‘the body’ is generally viewed and treated as an object, albeit a highly fetishized one, and as a ‘commodity’ that can be bartered, sold or stolen in divisible and alienable parts” (Sheper-Hughes 1). The very concept underpinning ChameleonMask is just that – the human body is simply another object that can be “cashed in” within the neoliberal market. Surrogates become unidentifiable, humanoid machines – or do they?

UNMASKING THE BODIES

Those who would become ChameleonMask surrogates are not identity-less, despite their reduction to a body with a tablet-face. These people have pasts, family and community ties, and motivations for becoming a surrogate. In this same vein, Uber has been criticized for its hiring practices that target the economically disadvantaged – “For workers who have few employment opportunities that come with benefits to begin with, Uber becomes a relatively lucrative job for the economically vulnerable” (Zwick 686). Because of this reduction of the human being to a faceless body, it is important to consider how identity might play a role in the future business model of ChameleonMask, the protections for surrogates, and the reinforcement of the cycle of oppression.

Recently, a driver for Lyft (similar to Uber) was attacked by her passenger on the basis of her trans identity. The driver, Standing-Owl, makes an interesting point about the perception of Lyft/Uber drivers – and most workers in the gig economy – when she says, “We’re not taken seriously, because we don’t count as people. In most people’s eyes, we’re trash,” (Maurice). Looking to ChameleonMask, it is reasonable to assume this same issue could arise. Despite the tablet plastered to the face, discrimination against surrogates could exist simply due to their status as surrogates.

BODIES FOR RENT: A CONCLUSION

While this pondering about ChameleonMask may seem more like an episode of Black Mirror, thinking through the implications of ChameleonMask offers valuable insights into the gig economy and the commodification of the body via digital technologies. In just a few years, it will be possible to rent a human being to act as a physical manifestation of yourself — rather, to act as your body. As I have touched on, this new technology makes the distinction between human and machine even harder to define as it exploits the human body in the name of technological advancement. It also calls attention to working conditions under the gig economy. However, this blog post is simply scratching the surface of examining ChameleonMask. As with any new media technology, it is important to step back and examine the real-world, human implications. Understanding these implications may help you justify why you sent a stranger with an iPad strapped to their face into your grandmother’s home!

SOURCES:

“ChameleonMask: Embodied Physical and Social Telepresence Using Human Surrogates.” Rekimoto Lab, 3 Feb. 2018, https://lab.rekimoto.org/projects/chameleonmask/.

Maurice, Emma Powys. “Taxi Driver Quits after Being Attacked by Drunk Passenger for Being Transgender.” PinkNews, 13 Sept. 2019, https://www.pinknews.co.uk/2019/09/13/lyft-trans-woman-taxi-driver-marla-standing-owl-oregon/.

Minsky, Marvin. “Telepresence.” Omni, June 1980.

Scheper-Hughes, Nancy. “Bodies for Sale – Whole or in Parts.” Body & Society, vol. 7, no. 2-3, 2001, pp. 1–8., doi:10.1177/1357034×0100700201.

Slater, Mel, and Sylvia Wilbur. “A Framework for Immersive Virtual Environments (FIVE): Speculations on the Role of Presence in Virtual Environments.” Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments, vol. 6, no. 6, 1997, doi:10.1162/pres.1997.6.6.603.

Thomas, Sujin. “Japanese Researchers Are Experimenting with a Way for People to Be in Two Places at Once – Through Strapping a Screen to Another Person’s Face.” Business Insider, Business Insider, Singapore, 1 Feb. 2018, https://www.businessinsider.com/chameleonmask-could-allow-people-to-be-in-two-places-at-once-2018-2?international=true&r=US&IR=T.

Zwick, Austin. “Welcome to the Gig Economy:

Neoliberal Industrial Relations and the Case of Uber.” GeoJournal, vol.

83, no. 4, Dec. 2017, pp. 679–691., doi:10.1007/s10708-017-9793-8.