The Illusion of Choice: On the Datafication of User Interactivity in AI Storytelling

AI technologies have found their way to yet another field in the media landscape: film & television. While some claim AI technologies are revolutionising storytelling, others are critical of the implications involving user participation and interactivity.

“The fascination with cinema is rooted in the consumer desire for peeping into others’ lives”

(Elnahla 4)

When Netflix’s popular TV show Black Mirror released Bandersnatch – an interactive film-like episode that chronicled the existential plight of a young, aspiring video game programmer – audience responses were highly diverse. While some viewers relished in their new-found ability to control what they were watching (Chmielewski), others were displeased with the interactive feature (Homonoff). And rightly so, too, given that at the crux of interactive storytelling lies the conflict between narrative control and interactivity (Cavazza et al).

Proliferation in the development of AI technologies has opened up new spaces for the hybridisation of different mediums. As a result, new sets of affordances and constraints are attributed to these new, hybrid media systems. AI storytelling is considered a hybrid of film and video-gaming (McSweeney), each of which has its unique set of affordances. Combining them, then, creates a new visual experience: one involving a story-line that is not only influenced by, but also depends on user intervention. To many viewers, this is empowering as it means they get to be a part of the story’s unfolding, and it also implies that their opinion is crucial to the progression of the plot (Chmielewski).

User participation in the audiovisual medium is not necessarily a new concept. In 1999, the term ‘spect-acteur’ was coined to describe spectators that are active rather than traditionally passive (Ivars-Nicholas & Martinez-Cano). Moreover, the popularity of video games has rendered the public accustomed to and expectant of having some level of control over what they’re experiencing. However, interactive techniques have only recently been introduced to the cinematic community, and these developments have not yet garnered much interest (Cavazza et al). Instead, interactivity in film has raised much criticism and commentary, particularly with regard to the debate of free will vs. determinism (Mathews).

The free will vs. determinism is a highly contested debate in discourses regarding AI technologies. Determinism refers to the notion that free will is an illusion (Wegner). Let us take Bandersnatch, for example. The progression of the storyline relies on our [the viewers] decisions. At each juncture, we are presented with choices for us to make and our protagonist Stefan to follow. We are able to choose our own montage of the narrative (Ivars-Nichols & Martinez-Cano). Some choices are seemingly mundane, such as choosing which cereal Stefan should eat for breakfast. However, as the film progresses, we are presented with heavier and more provocative options, such as taking/not taking LSD and killing/not killing Stefan’s father.

Being presented with these options that affect the unfolding of Stefan’s journey gives us the illusion of choice (Mathews). While we are being led to believe our choices are influencing the plot, it should be noted that these choices are limited and pre-defined. Moreover, while we are busy satisfying our desire to control Stefan, Netflix is profiting of our choices – monitoring, tracking and storing our choices as data. Their algorithms stay hard at work, tailor-making unique experiences for different viewers based on the information garnered from viewing choices, online activity, and the decisions we make for Stefan. Therefore, the more control we are seemingly given, the more we are manipulated (Elnahla).

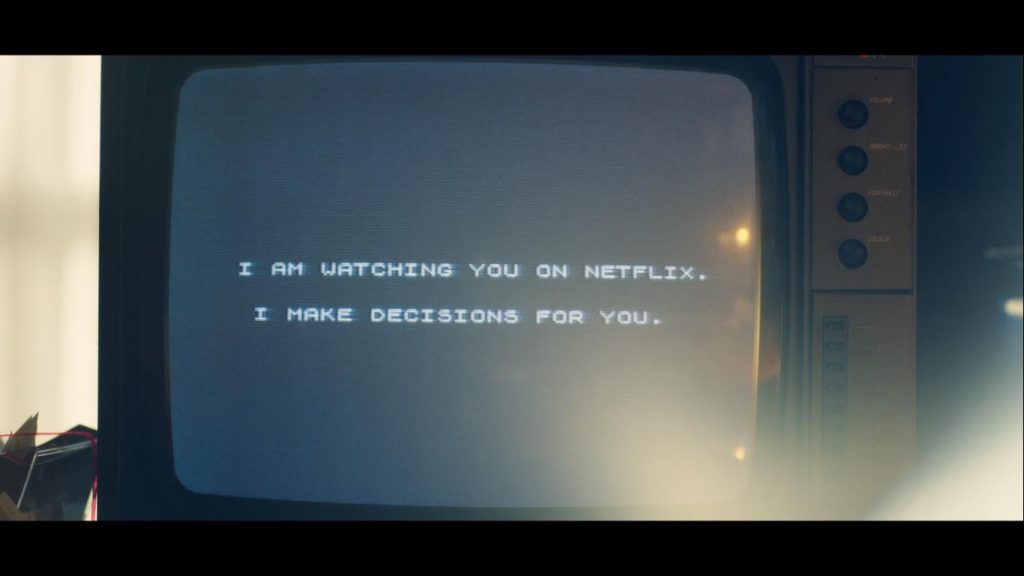

Following the Black Mirror tradition, Bandersnatch offers a dystopian narrative with underlying themes of technological determinism. Moreover, certain aspects of its plot are eerily parallel to the reality of the viewers. For example, in one possibility of plot progression, Stefan realizes that he is being controlled by viewers of a 21st century online television platform:

Interactive film has considerable implications for data mining, production and advertising, to say the least (Elnahla 1). However, this hybrid genre offers much to appreciate. The interactive features and algorithmic functions offer a customised experience for viewers – to some extent. Seeing the consequences of our decisions enables us to relate to Stefan more closely and, as a result, gain a more immersive viewing experience.

The collaboration of different mediums, as is exemplified by Bandersnatch, is characteristic of the transmedia narrative. The transmedia narrative refers to processes by which different mediums collaborate, each offering a unique contribution, to the formation of the ‘global story’ (Ivars-Nichols & Martinez-Cano). The transmedia narrative stresses the importance of each individual medium – a notion that alludes to media theorist Marshall McLuhan’s adage, “The medium is the message.”

That being said, it is most fitting to view AI storytelling through a lens of hybridity. Despite its constraints, the hybrid media system of AI storytelling reveals an intriguing new art form. Moreover, not only are viewers offered a unique, personal viewing experience, but are also able to engage in new discourses triggered by this new media form. For example, now, viewers will no longer discuss merely what happened in last night’s episode, but will discuss what happened to [me] compared to what happened to [you]. Each viewer is in charge of their own unique organization of the story.

Nevertheless, we should maintain an awareness of what is happening behind the scenes of this exciting new media form. It is worth being reminded of how these new forms are being created – how data is being custom generated for individual viewers, and how meticulously user activity is being monitored in order to generate these personalised experiences. It is as interesting as it is daunting to consider the colossal scales on which data is collected and analysed, based on such minute and seemingly harmless actions such as clicking a button. As viewers, we can only wonder how choosing Frosties over Sugar Puffs over breakfast helps Netflix analyse and profit off our viewing desires and preferences.

References:

“Black Mirror: Bandersnatch.” IMDb, IMDb.com, www.imdb.com/title/tt9495224/mediaviewer/rm3985274112

Cavazza, Marc, et al. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/220851669_Interactive_storytelling_from_AI_experiment_to_new_media.

Chmielewski, Dawn C. “Is Netflix’s ‘Black Mirror: Bandersnatch’ Just Another Video Game?” Deadline, 28 Dec. 2018, https://deadline.com/2018/12/netflix-black-mirror-bandersnatch-another-video-game-1202526956/.

Elnahla, Nada. “Black Mirror: Bandersnatch and How Netflix Manipulates Us, the New Gods.” Consumption Markets & Culture, 2019, pp. 1-6, doi:10.1080/10253866.2019.1653288

Homonoff, Howard. “Is Netflix’s ‘Bandersnatch’ The Future of Storytelling, Or The End?” Forbes, Forbes Magazine, 6 Feb. 2019, https://www.forbes.com/sites/howardhomonoff/2019/02/05/is-netflixs-bandersnatch-the-future-or-the-end-of-storytelling/#3a337ab4126b.

Ivars-Nichols, Begoña, and Francisco Julian Martinez-Cano. “Interactivity in Fiction Series as Part of Its Transmedia Universe: The Case of Black Mirror: Bandersnatch.” Narrative Transmedia, https://www.intechopen.com/online-first/interactivity-in-fiction-series-as-part-of-its-transmedia-universe-the-case-of-black-mirror-bandersn.

Matthews, Joshua. “Netflix Review: Bandersnatch.” Faculty Work Comprehensive List, 18 Jan. 2019, https://digitalcollections.dordt.edu/faculty_work/1031

McSweeney, Terence, and Stuart Joy. Through the Black Mirror: Deconstructing the Side Effects of the Digital Age. Palgrave Macmillan, 2019.