Can we trust apps to solve our problems? SuperBetter – promises to improve overall conditions of health

Are you suffering from stress and anxiety, are you feeling a little down or did you just have a bad day? Among the vast amount of apps available, there is an app that can “unleash your heroic potential” and make you feel super better! (SuperBetter). The app named “SuperBetter” promises improved mental health and increased resilience (SuperBetter). SuperBetter is a health game designed app targeted for users who want to increase their “general wellbeing” or recover from serious illnesses and mental health associated problems (Cision). The app deals with serious health issues in an entertaining way.

There are many reasons people use the apps to deal with their health problems, essentially for convenience, because smart phones are with the owner 24 hours to provide immediate answers and support; and is also usually cheaper (or free) than a doctor’s appointment (Dennison et.al. 2). Besides, in a time when the demand for psychological medical help is at rise, the emergence and commodity of apps providing health support is definitely a thing to acknowledge (Leigh and Flatt 97). Considering the multitude of reasons of app usage in health intervention, the question arises: can we trust our health in the hands of the apps? To answer this question, this article will explore the case of SuperBetter app.

What is SuperBetter and how does it work?

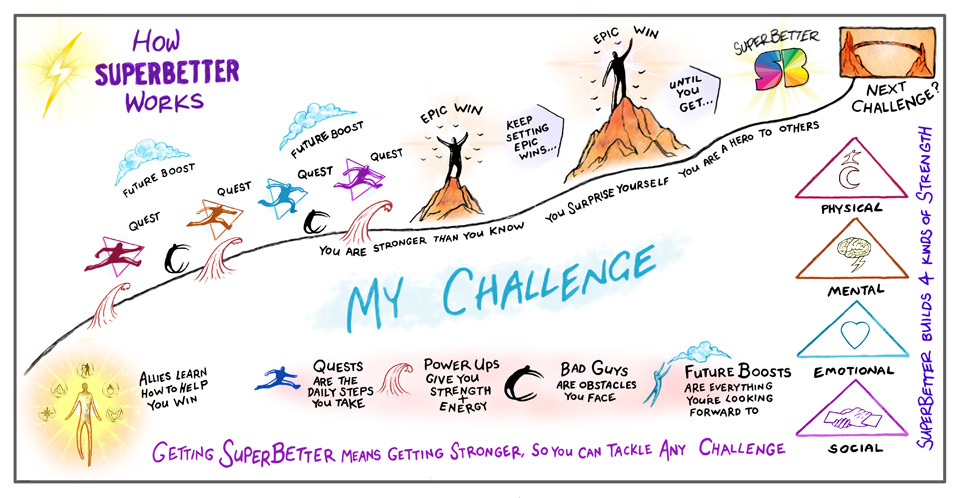

SuperBetter app is a “gamified” user experience based on the idea of building resilience on four levels: social, physical, mental and emotional. The game is focused on achieving health goals of different kinds, but with non-real specific goal (Payne et. al. 8). The user can choose which challenges to complete as long as the necessary number of challenges are completed per day. The challenges are specifically about completing 3 quests, activating 3 power-ups and battling one bad guy per day (SuperBetter app).

The designer of the game, Jane McGonigal invented the first version of the game named Jane: The Concussion Slayer, which helped her recover from a concussion (Giardina). The success she encountered with the first game experience led her to develop a new app, SuperBetter, which was intended for a larger audience wishing to recover from injuries or improve their wellbeing. Jane emphasizes that the app helps in treating serious mental health problems (McGonigal). Moreover, she encourages people to use the app regardless of how serious the mental condition is. Her argument? “SuperBetter is backed by science” (SuperBetter). McGonigal presents numbers to show how the game could lead to ten extra years of life if performing the challenges of the game (McGonigal). But should the data presented be trusted for dealing with health?

Analysis and Discussion

One of the issues with apps is their ‘shareability’ option and its effects on privacy. As most of the apps require the user to share his/her activity, goal or achievement, the SuperBetter app is not an exception. Indeed, as I went through my list of activities on the app, I noticed that there is a share button for Twitter or Facebook (SuperBetter app). A study performed by Dennison et. al showed that users are not happy to share their information with the social media, especially if the information concerns health related issues (Denisson et. al. 5). Dennison et. al explains that the users can feel uncomfortable or even ashamed to make their problems and insecurities public (Denisson et. al. 5). Moreover, the app encourages users to invite their friends to join the app, motivating that “the game is more fun when you have allies” (SuperBetter app). Thus, as with most of the apps and social media, the commercial aspect of the game is noted. The more users join the game, the more popular the game becomes. The users themselves participate in the process of making the app successful and popular by inviting their friends. So, is the app really passionate about helping users or is the health issue just a pretext for commercial use? It is a question worth considering if to evaluate the socio-cultural implications of an app. Studies have been conducted to show how an app’s environment and interface depends on the economic and political interests behind it (Light et. al. 8).

On the other side of the spectrum, some authors argue that health apps are recommended and actually beneficial for health if not used for long term. Chou et. al believes that the app should not be used for treating serious mental health problems. It can, however, inspire ideas to activities that could increase the mood. As argued by Chou et. al. , the app lacks structure and coherence, so it cannot aid people in need of serious help (118). That is particularly because the functions of the game are not addressed on a personal level but are rather general. It is recommended to use the app if the user has a clear goal to become better. The author therefore recommends to use the app as an addition to the help of a professional help (Choi et. al. 117).

Similarly, in the study presented by Payne et. al., SuperBetter scored high in the ability to change health behaviour compared to other games (7). In particular, the features of the game such as self-monitoring, goal-setting, feedback, modeling and rewards proved successful to contribute to behaviour change (Payne et. al. 8). At the same time, the author emphasizes that SuperBetter was the most expensive app among the other analysed (Payne et. al. 8). It is uncertain whether the designers already knew how to design a successful health game, which could explain why the game became successful in a commercial sense.

Conclusion

Some of the literature investigated has shown arguments for both strengths and limitations of using SuperBetter in dealing with health issues. It should be noted that research is limited and in early stage despite the significant uses of apps in health issues (Dennison et. al. 2). Nevertheless, it can be highlighted at this point that health related apps should be used with caution, as it can have consequences on sharing private information. Besides, research should be further conducted in order to understand whether apps can be scientifically reliable and effective in dealing with health issues (Leigh and Flatt 97).

References:

Chou, Tommy, et al. “Multimedia Field Test: Evaluating the Creative Ambitions of SuperBetter and Its Quest to Gamify Mental Health.” Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, vol. 24, no. 1, 2017, pp. 115–120., doi:10.1016/j.cbpra.2016.10.002.

Dennison, Laura, et al. “Opportunities and Challenges for Smartphone Applications in Supporting Health Behavior Change: Qualitative Study.” Journal of Medical Internet Research, vol. 15, no. 4, 2013, doi:10.2196/jmir.2583.

“Everyone Has Heroic Potential.” SuperBetter, https://www.superbetter.com/.

Giardina, Carolyn. “Jane McGonigal: How Video Games Can Change Your Life” The Hollywood Reporter, 7 Aug. 2012. https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/jane-mcgonial-siggraph-speaker-video-game-356472

Leigh, Simon, and Steve Flatt. “App-Based Psychological Interventions: Friend or Foe?: Table 1.” Evidence Based Mental Health, vol. 18, no. 4, Dec. 2015, pp. 97–99., doi:10.1136/eb-2015-102203.

Light, Ben, et al. “The Walkthrough Method: An Approach to the Study of Apps.” New Media & Society, vol. 20, no. 3, Nov. 2016, pp. 881–900., doi:10.1177/1461444816675438.

McGonigal, Jane. “The game that can give you 10 extra years of life”, 2012. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lfBpsV1Hwqs

Payne, Hannah E, et al. “Health Behavior Theory in Physical Activity Game Apps: A Content Analysis.” JMIR Serious Games, vol. 3, no. 2, 2015, doi:10.2196/games.4187.

“Superbetter labs ‘SuperBetter’ Game Design Director Wins 2012 Rising Star Award.” News Powered by Cision, https://news.cision.com/i-o-communications/r/superbetter-labs–superbetter–game-design-director-wins–2012-rising-star-award,c9235580.