“Dadfindboy”: How activists in Hong Kong are hijacking state tools of surveillance

Protesters in Hong Kong have flipped a tool of government surveillance on its head, transforming it into an instrument of crowdsourced counter-surveillance. Here’s how a popular channel on the cloud-based messaging platform Telegram has reversed the invasive gaze of the state and, in the process, challenged the parameters of what is allowed to be seen, perceived, and known.

Digital activism in the face of state suppression

On July 18, 29 year-old Colin Cheung, a subscriber of Telegram channel “Dadfindboy” was apprehended at a mall on suspicion of “conspiring and abetting murder” by four plainclothes officers, who did not immediately identify themselves.

A month earlier, using Google technology, he had built an algorithm, which could identify police officers from a small pool of photos online. His detention solidified his fears. “I think it’s more possible to see that Hong Kong will become China,” he told The New York Times (Mozur 2019).

He isn’t wrong. Every year, the Hong Kong police send 150 officials to the mainland for “ideological and practical training” (Mahtani 2019), which gives credence to the anxieties over resinicization, i.e. the policy of rendering Hong Kong more dependent on China (Adorjan & Yau 2015).

As the surveillance apparatus of Hong Kong has expanded its scope to include social media, protesters have partially returned to analogue methods of combatting surveillance, like covering their faces, aiming laser pointers at or spray painting surveillance cameras, and using single-ride public transportation tickets (Mozur 2019; Mahtani 2019).

The recent protests in Hong Kong, also known as the Anti-Extradition Law Amendment Bill Movement, have demonstrated synergy between physical and technologically mediated activism, what sociologist Nathan Jurgenson has termed Augmented Reality. Proposing a critique to the digital-dualist discourse, he wrote: “Digital and material realities dialectically co-construct each other” (Jurgenson, 2009).

For the younger generation of digital natives or netizens, social media serve as platforms for political and civic participation. These netizens have come of age with Facebook, Twitter, Tumblr, etc. and have often developed their political consciousness through these venues. In Hong Kong, where social media network size has been shown to positively influence offline civic participation (Chen et al. 2016), youth born in the 1990s and after are increasingly becoming the face of political activism against the mainland-controlled post-colonial government (Adorjan & Yau 2015).

It has been pointed out (Lee 2018) that, under suppression, groups, whose repertoires of tactics are severely limited, have turned to “hidden transcripts” on social media, that is producing action that evades normative conceptions of “the political”.

It is therefore unsurprising that protesters are weaponising the very tools used in their surveillance, not only to protect their identities, but also to expose instances of misconduct. They are engaging in what Wood and Thompson (2018) call crowdscourced counter-surveillance, which they define as “the use of knowledge-discovery and management crowdsourcing to facilitate surveillance discovery, avoidance, and counter-surveillance”.

Mobile and new media in particular afford [1] new opportunities for gazing back at institutions by “capturing, storing, and distributing information on surveillance actors” (Wood & Thompson 2018: 34).

Counter-surveillance as activism

Monahan (2006) defines counter-surveillance as “intentional, tactical uses, or disruptions of surveillance technologies to challenge institutional power asymmetries”. Marx (2003, 384) also suggests that counter-surveillance involves “turning the tables and surveilling those who are doing the surveillance”. Mann (2002), on the other hand, considers these tactics to be a form of sousveillance—the use of surveillance techniques to monitor agents of state power in order to document misconduct and foster accountability.

Contemporary policing is becoming subject to increased scrutiny or an “increased visibility” (Goldsmith 2010), particularly in the US, where instances of anti-black police brutality have been documented and broadcast on social media in an effort to shed a light on the phenomenon.

At the same time, the gaze of the camera is in many senses undesired and, therefore, unauthorised. It disrupts the aesthetic order established by the police, prompting a crackdown, a sort of “war on photography” (Wall & Linnemann 2014). This war, much like the “war on drugs” or “the war on crime”, is ostensibly not about the cameras themselves, but instead against the “unruly” populations that yield them to openly defy state power.

The counter-stare is therefore deemed “aggressive, overreaching, an inherent indictment of police authority” (Wall & Linnemann 2014, 141), as it attempts to repoliticise a contested public and social space. The very act of documentation implies distrust, not only in the individual state officers, but in the state itself.

Telegram: How to weaponise the tools of state suppression

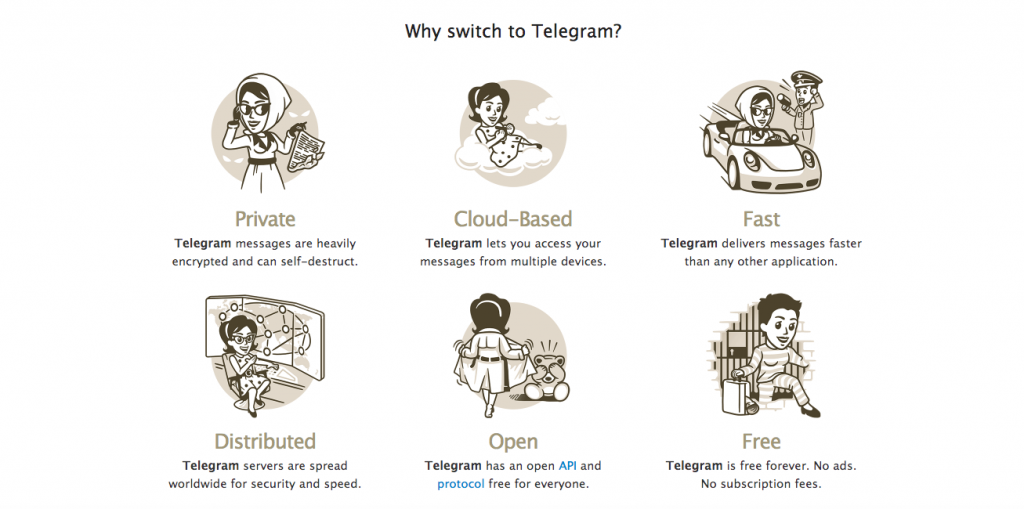

Telegram is a not-for-profit, encrypted, cloud-based messaging app that describes itself as a combination of SMS and email. It firmly distinguishes itself from “Big internet companies” like Facebook and Google, by emphasising its commitment to privacy. In fact, Telegram claims to protect both private conversations and personal data: “We don’t use your data for ad targeting, we don’t sell it to others, and we’re not part of any mafia family (sic) “family of companies”. It quickly becomes apparent why activists might favour this particular platform.

In the days leading up to the protests, Telegram rose to the top spot of the Hong Kong App Store (Mahtani 2019). “Dadfindboy”, one of the leading channels on the platform, was created in response to police officers not wearing identification badges (Ehrenkranz 2019) “Dadfindboy” is a play on the name of a popular Facebook group created under the pretence of helping mothers find their children, which later became a tool for pro-government groups to collect photos of protesters.

The channel, which has garnered more than 50,000 followers, is reportedly responsible for the dissemination of sensitive information about officers, a practice called “doxxing”, through posts including social media posts and intimate and family photos (Mozur 2019; Ehrenkranz 2019).

The channel also appears to advocate for violence against police officers, including tips on how to shoot a slingshot and how to make a blowtorch, and crude surveys on the best way to handle police, with options ranging from prison to the guillotine, per The New York Times. There is no actual evidence indicating that any violent acts can be attributed to the activities on the channel.

Social media aren’t merely tools in the hands of users, but an active mediator. Their “algorithmic architecture, data structures, surveillance practices, and technologically inscribed values” inform counter-surveillance practices (Wood & Thompson 2018, 35). For example, since Telegram claims that the content uploaded remains private among the participants of a given group, requests related to allegedly illegal content aren’t processed.

The limits of counter-surveillance

While it is true that tactics of counter-surveillance can help foster accountability and often are the sole defense of subjects against state suppression, it’s important to avoid falling prey to an uncritical technophilia.

Through its features, Telegram affords protection from data collection and monitoring and the fostering of a safe space, where protesters can share information and facilitate organising, therefore becoming particularly appealing to activists who desire a respite from the invasive gaze of the state. But the platform’s stance on illegal content creates an ethical grey area, as it also affords the dissemination of unsubstantiated information that could endanger individuals and their families.

It’s therefore crucial to consider the “ethics, appropriateness, and proportionality of surveillance”. Crowdsourced counter-surveillance may engender harmful outcomes, both for those who enact it, in the form of retaliation from the police (as we see in the case of Colin Cheung), and its objects.

Conclusions

Activism doesn’t occur in a vacuum and neither does media technology (Kaun & Uldam 2017). The advent of practices like the one embodied by “Dadfindboy” is firmly situated within the context of increased surveillance in Hong Kong. Marked by the anxieties of resinicization, digital activism has evolved to include defense strategies against state surveillance. These include the photographic counter-stare (Wall & Linnemann 2014), which here doesn’t necessarily only document police misconduct, but returns the gaze to capture the very identities of the state agents.

We seem to be witnessing a reversal of optics, a shift away from the panopticism Foucault envisioned, where “the few watch the many”, to a synopticism, where “the many watch the few” (Mathiesen 1997)—or, perhaps more accurately, “those being watched also watch back” (Welch 2011, 304).

The very existence of these unauthorized photographers raises important questions, such as who gets to look and how? Whose identity warrants protection? Is the state and its agents above scrutiny? What are the limits of (digital) activism, especially in the context of authoritarianism?

There is a particular tinge of irony in the appropriation of government tactics by protesters, but these guerrilla measures are no match to the pervasive surveillance apparatus in the region.

As Monahan (2006) explains, since counter-surveillance movements respond to power inequities, they do disrupt status quo politics, but only on an individualised basis, giving ample opportunity to those with institutional power to reconfigure and optimise their control mechanisms.

And, of course, there remains a critical question: What does it say for our activism, if we reproduce the reactionary techniques of those we claim to oppose?

[1] The notion of affordances first appeared in ecological psychology and was later developed in design studies. It broadly refers to what an object, platform, app, etc. allows its users to do. As an analytical tool, affordance finds many applications in media studies (Davis & Chouinard 2017).

References

Adorjan, Michael and Ho Lun Yau. “Resinicization and Digital Citizenship in Hong Kong: Youth, Cyberspace, and Claims-Making.” Qualitative Sociology Review 11.2 (2015): 160-178.

Ataman, Bora and Barış Çoban. “Counter-surveillance and alternative new media in Turkey.” Information, Communication & Society 21.7 (2018): 1014-1029.

Chen, Hsuan-Ting, Michael Chan and Francis L.F. Lee. “Social media use and democratic engagement: a comparative study of Hong Kong, Taiwan, and China.” Chinese Journal of Communication 9.4 (2016): 348-366. DOI: 10.1080/17544750.2016.1210182

Davis, Jenny L. and James B. Chouinard. “Theorizing affordances: From request to refuse.” Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society 36.4 (2017): 241-248. DOI: 10.1177/0270467617714944

Jurgenson, Nathan. “Towards Theorizing an Augmented Reality” 5 October 2009. Sociology Lens 19 September 2019. <https://thesocietypages.org/cyborgology/2011/09/13/digital-dualism-and-the-fallacy-of-web-objectivity/>.

Kaun, Anne and Julie Uldam. “Digital activism: After the hype.” New Media & Society 20.6 (2017): 2099-2106. DOI: 10.1177/1461444817731924

Lee, Ashley. “Invisible networked publics and hidden contention: Youth activism and social media tactics under repression.” New Media & Society 20.11 (2018): 4095– 4115. DOI: 10.1177/1461444818768063

Mahtani, Shibani. Masks, cash and apps: How Hong Kong’s protesters find ways to outwit the surveillance state. The Washington Post. 15 June 2019. 18 September 2019 <https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/masks-cash-and-apps-how-hong-kongs-protesters-find-ways-to-outwit-the-surveillance-state/2019/06/15/8229169c-8ea0-11e9-b6f4-033356502dce_story.html>.

Mann, Steve. Sousveillance: secrecy, not privacy, may be the true cause of terrorism. 2002. 19 September 2019 <http://www.wearcam.org/sousveillance.htm>.

Monahan, Torin. “Counter-surveillance as Political Intervention?” Social Semiotics 16.4 (2006): 515-534. DOI: 10.1080/10350330601019769

Mozur, Paul. In Hong Kong Protests, Faces Become Weapons. The New York Times. 26 July 2019. 18 September 2019 <https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/26/technology/hong-kong-protests-facial-recognition-surveillance.html>.

Wall, Tyler and Travis Linnemann. “Staring Down the State: Police Power, Visual Economies, and the “War on Cameras”.” Crime, Media, Culture 10.2 (2014): 133-149. DOI: 10.1177/1741659014531424

Welch, Michael. ” Counterveillance: How Foucault and the Groupe d’Information sur les Prisons reversed the optics.” Theoretical Criminology 15.3 (2011): 301-313. DOI: 10.1177/1362480610396651

Wood, Mark A. and Chrissy Thompson. “Crowdsourced Countersurveillance: A Countersurveillant Assemblage?” Surveillance & Society 16.1 (2018): 20-38.