Trick-or-Treating Dressed as Apple

Only with a mask was it possible for Romeo to disguise his true identity and enter the Capulets’ ball to meet Juliet. An unimaginable feat in today’s world of digital footprints and traces. With Apple’s recently announced sing-in alternative we might be looking at a new type of mask, a mask in the shape of an Apple logo.

Applause

A roaring cheer goes through the crowd as Craig Federighi announces Sign in with Apple at the World Developers Conference 2019 (Apple 40:45). It is Apple’s answer to sign-in methods that ask the user to log in via a social account such as Google or Facebook in order to get a more personalized experience. Apple’s alternative is accessible to anyone with an Apple ID and it is easily implementable for developers. The promise is simple. “Fast, easy sign in. Without the tracking” (ib. 41:02). A bold claim and one that needs further examination. Is Sign in with Apple merely a canny marketing move or is Apple indeed becoming our online-privacy vigilante?

Sign in with Me

Single sign-on platforms are long past their infancy and have become omnipresent in our digital day-to-day life. What they offer to the user is, on first glance, convenience. A click of a button, another one to verify and the login process is complete. What is not as apparent, however, are the privacy implications of such a login procedure. As Kontaxis et al. illustrate, there are several disadvantages associated with it: the user’s social identity and circle can be revealed, the user is likely to lose track of which applications have access to personal information, and advertisements can be propagated without approval (322). It is no surprise, then, that Apple is trying to market their alternative as especially privacy oriented. But how do these single sign-on platforms work and how does Apple’s differ?

OAuth

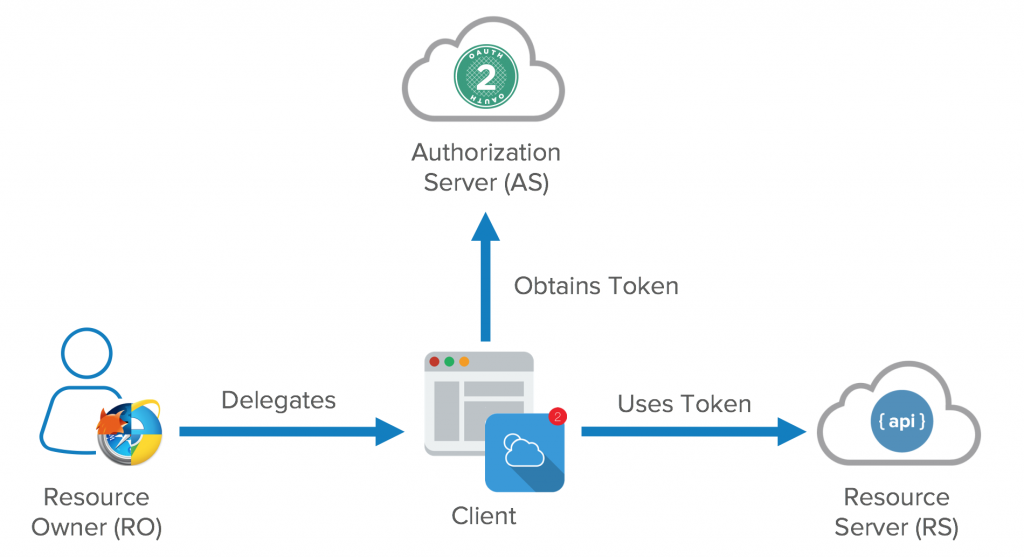

The primary method for implementing single sign-on functionality across multiple websites is a protocol called OAuth. It allows a secure API-authorization for desktop, web and mobile applications without the user having to create a new account (Y). Instead, it can use the personal information already stored with services like Google or Facebook. It is important to note that the user’s passwords for any of these services are at no stage revealed. Instead, OAuth assigns a so-called client ID and secret, basically a password, to the third-party site. So, a website can only access or modify the information it explicitly states it will (Hammer-Lahav). While providing protection for the user’s password, it is not obvious that the user’s privacy is protected. With shared information such as name, email address, gender, friend circle and sometimes profile picture as well as the often-overlooked permission to modify the user’s Facebook page, the protocol does not provide an optimal solution.

What does Apple do?

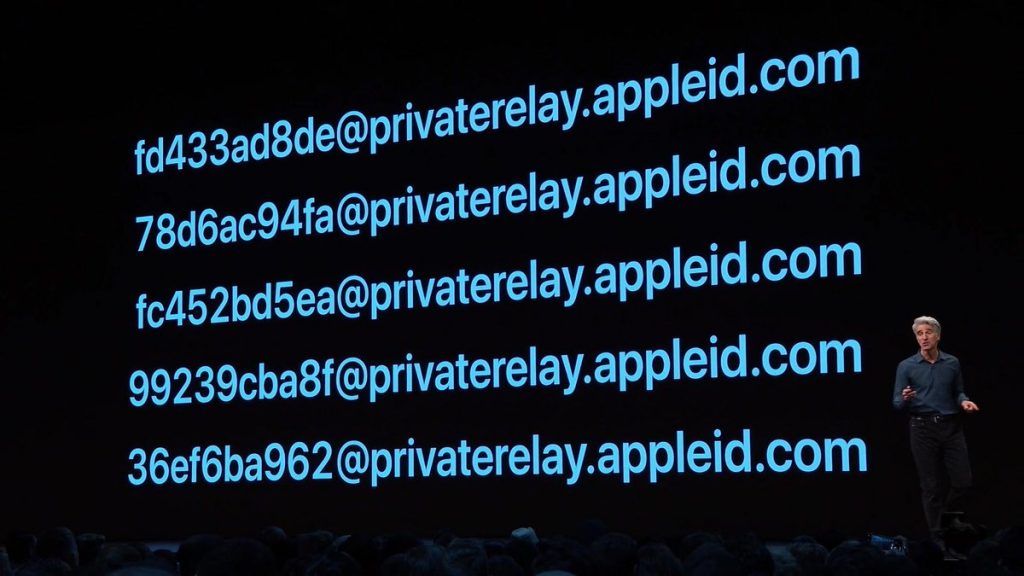

Interestingly, and for developers thankfully, Apple’s alternative also uses the standardized OAuth protocol (Parecki). This makes the implementation for developers much easier. Apple’s approach nevertheless differs in two major ways. Firstly, developers cannot follow the typical route and register their applications with OAuth providers (ib.). Since Apple’s API is tied to the whole iOS app ecosystem, they have to go through the Apple Developer Portal. Secondly, the user has the choice of what information is provided to the app. While the name associated with the user’s Apple ID will still be used, the associated email address can be hidden. This would pose a unique problem for apps that need to send e-mails to the users. The solution: Apple generates a unique, random email address for each app the user wants to log into. The emails sent to said random addresses will be forwarded to the user’s Apple ID address. This ensures that developers cannot link a user to their email address. In addition, Apple is making Sign in with Apple mandatory for all apps that use third-party sign-in options (Apple).

What does it mean for us?

Both developers and users could profit from this system. The most apparent advantages for developers are “built-in two-factor authentication support, anti-fraud detection and the ability to offer a one-touch, frictionless means of entry into their app” (Perez). For users, on the other side, the advantages concern their privacy. They can use a familiar system that works just as fast as with other services without giving away too much information or unwanted permissions. Since a unique, random email address is generated for each app, users can turn off email notifications per app. In addition, developers cannot use email addresses to correlate users between apps because no link between user and generated email address can be made. What is striking about Apple’s proposition is not merely the use of disposable email addresses, but the way in which they are implemented. As Perez notes, “this is the first time a major technology company has allowed customers to not only create these private email addresses for sign-ins to apps, but to also disable those addresses at any time if they want to stop receiving emails at them” (ib.).

Conclusion

With the ever-growing concern for privacy in a digital age and considering that more than 250 million users might not realize the privacy implications of opting-in with single sign-on platforms (Kontaxis et al. 321), the question remains: Has Apple found a solution and crafted the software equivalent to the venetian mask with its sign-in alternative? Well, not really. It promises “Fast, easy sign in. Without the tracking” (Apple 41:02). It seems as though they have definitely made it fast and easy. Claiming that it would eradicate tracking is premature, however. Ultimately Sign in with Apple does not radically solve the privacy concerns of our times, but instead radically persuades users to trust one company over another.

References

Apple. Sign in with Apple – Apple Developer. https://developer.apple.com/sign-in-with-apple/. Accessed 22 Sept. 2019.

Apple. WWDC 2019 Keynote — Apple. YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=psL_5RIBqnY. Accessed 22 Sept. 2019.

Hammer-Lahav, Eran. Introduction — OAuth. https://oauth.net/about/introduction/. Accessed 22 Sept. 2019.

Kontaxis, Georgios, et al. “Minimizing Information Disclosure to Third Parties in Social Login Platforms.” International Journal of Information Security, vol. 11, no. 5, Oct. 2012, pp. 321–32. Crossref, doi:10.1007/s10207-012-0173-6.

Parecki, Aaron. “What the Heck Is Sign In with Apple?” Okta Developer, https://developer.okta.com/blog/2019/06/04/what-the-heck-is-sign-in-with-apple. Accessed 22 Sept. 2019.

Perez, Sarah. “Answers to Your Burning Questions about How ‘Sign in with Apple’ Works.” TechCrunch, http://social.techcrunch.com/2019/06/07/answers-to-your-burning-questions-about-how-sign-in-with-apple-works/. Accessed 22 Sept. 2019.

Y, Ratros. “Understanding OAuth2 and Building a Basic Authorization Server of Your Own: A Beginner’s Guide.” Medium, 28 Feb. 2019, https://medium.com/google-cloud/understanding-oauth2-and-building-a-basic-authorization-server-of-your-own-a-beginners-guide-cf7451a16f66.