When platforms support emergency services: the case of Namola in South Africa.

People are increasingly relying on technology to improve their everyday life, and new media like social media platforms are progressively providing a safe space for those in difficulty.

Smartphones have already proven to be a great medium when it comes to behavioral intervention. They tend to be in the hands of the owner all day long and they can provide convenient and less stigmatizing interventions, facilitating the sharing of data with professionals (Dennison, Laura et al. 2013).

This is true with health-related apps, but mobile technology can also assist with the reduction of violence for those who find themselves in potentially dangerous situations, as it provides platforms that are “easily accessible, crowd sourcing and affordable scalability” (Mandapati et al. 2015). In addition, the ability of new mobile phones to track the location of the users is raising the possibility and perspective of automated tracking of specific behaviors, in order to tailor precise and defined interventions (Dennison, Laura et al. 2013).

What’s happening in south africa?

Nowadays, South Africa is facing high rate of violent crimes like murders, rapes, assaults and robbery. This is caused by multiple factors, both social and economic, like the high levels of inequality and poverty, the subculture of violence and its normalization. Moreover, a lot of people are vulnerable and easily exposed to risky situation. This is often see as the result of an unstable living and a lack of social inclusion (Bruce, 2009).

Nowadays new apps are emerging, exploiting their peculiar characteristics in order to be a concrete help in case of emergency. This is exactly what Namola does.

An overview of the app

The app was introduced as an intermediate to the South African Police Service, as the country is facing growing crime rates. Yusuf Abramjee, Namola chief ambassador, stated that the app aims to provide the victims a “new innovative way of contacting the police” (fin24, 2017).

It relies on GPS locations and a call centre, from which trained operators assist the users in need. The GPS tracks users’ location, in order to provide accurate coordinations to services such as police, fire departments and ambulances. One important feature of Namola is also the so called Family Safety feature, that let the users share their live location with family and trusted friends.

The psychological benefits of the app are numerous, as it is a free and reliable source of help, but on a larger scale, it can have an impact on society as well. Communications are faster and simpler, and this may encourage more and more people to report different crimes, also the non-violent ones, empowering the public-private partnership (Parks, 2017).

How does Namola work?

The interface of the app is intuitive, as it works mainly as a panic button. The process is built of three different steps : once the button is pressed, the operators are immediately warned, ready to verify the coordinations.

During the second phase an operator immediately gets in touch with the user, providing informations on how to face the situation.

Not always the victim is able to speak: in these cases, the app provides the possibility to not to speak, and victim and operator communicates through written texts. This helps overcoming situations of house robbery or hostage.

Once the operator is alerted, they immediately get in touch with the needed emergency service. In this way, the victim is constantly supervised by the Namola responders while the public services are reaching them.

A closer look

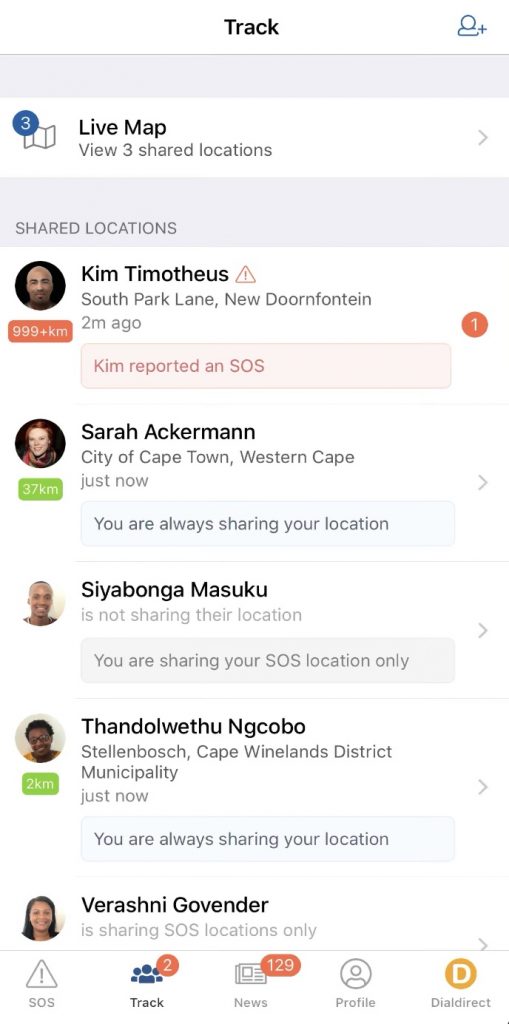

As already mentioned, of the most important feature of the app is Family Safety. It relies on GPS as well, providing a live location sharing function with the preferred contacts.

These are the so called emergency contacts, that are instantly alerted whenever Namola is used to request assistance. These contacts are also enabled to actively participate in case of emergency, as they can message the user or the Namola control room.

Moreover, Family Safety gives the possibility to receive real-time alerts whenever the emergency contacts arrive or leave a specific location. If this may sound invasive for users’ privacy, keep in mind that they have the chance to decide for how long and with whom share the live location.

Another important feature is the panic button: it lets the users to get in touch in real-time with a Namola operator, while the GPS provides them the exact location from which the request of assistance comes. The panic button is the most common app function when it comes to danger alert: most of them emit loud noises to scare the offender and attract attention, but others function as mediators between the victim and a source of help (https://www.dur.ac.uk/resources/sass/research/briefings/ResearchBriefing12-ProtectingWomensSafety.pdf)

Apart from Namola, an example of this feature is given by other apps, such as Circle of Six. This app is based on friendship, as it asks the users to pick up six different contacts of trusted people. Once the users feel in need or in danger, they can send an automated SMS message to the circle of contacts through the app (Westmarland et al., 2013).

In conclusion, Namola combines some already known features like alert button and live sharing locations with human operators that approach every user differently based on their particular situation.

This human-platform cooperation results in an effective help for those in need, as the success of the app may explain. In a few months it reached 80 000 users, and they are continuously growing. While South Africa is still in need to face the crime rates on a political and social scale, Namola works for individuals and families: its goals is to make people feel safe, offering a free and concrete help in the most efficient way.

References

Bruce, “Tackling Armed Violence”. Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation. February 2009. Retrieved 1 October 2018.

http://www.csvr.org.za/docs/study/6.TAV_final_report_13_03_10.pdf

Dennison et al. “Opportunities and challenges for smartphone applications in supporting health behavior change: qualitative study.” Journal of medical Internet research vol. 15,4 e86. 18 Apr. 2013, doi:10.2196/jmir.2583

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3636318/

Fin24, “Panic button app Namola goes national”, fin24tech ,10-11-2017

https://www.fin24.com/Tech/News/panic-button-app-namola-goes-national-20171109

Mandapati et al., “A Mobile Based Women Safety Application (I Safe Apps)”, IOSR Journal of Computer Engineering (IOSR-JCE) Vol. 17, Issue 1, Jan – Feb. 2015, PP 29-34

e-ISSN: 2278-0661,p-ISSN: 2278-8727

Parks, NAMOLA: AN INNOVATIVE WAY TO REPORT A CRIME IN SOUTH AFRICA, The Borgen Project, 27-11-2017

Westmarland et al. “Protecting Women’s Safety? The use of smartphone ‘apps’ in relation to domestic and sexual violence”. Durham Centre for Research into Violence and Abuse (CRiVA), September 2013.