Chinese Communist Youth League: Your Next Influencer

Social media platforms are easy to access, to use and could be seamlessly integrated within different cultures and social structures. They are an integral part of how new content is propagated online, hence making them important in political lives and daily lives. Such overall prominence in turn calls for public opinion manipulation techniques, most well known of which is propaganda.

Propaganda as defined by Merriam-Webster is “ideas, facts, or allegations spread deliberately to further one’s cause or to damage an opposing cause”. “Propaganda” as a notion is largely used in more political context, while referring to actions of states or government institutions.

One of the most active and vibrant digital spaces is in China, which could be viewed as an entirely different kind of space compared to the West (Computational Propaganda in China). Furthermore, the view on propaganda in China is different compared to the West. “Propaganda is not generally seen as having the same negative connotations as it does in the West” (Brady, 2009; Brady & Juntao, 2009 qtd in Computational Propaganda in China). Communist Party’s government also saw within a myriad of Chinese native social media an opportunity to cultivate party’s ideals (WhatsOnWeibo). Whereas propaganda in the West is emerging with the phenomenon of fake news going viral, which was brought to attention with 2016 US presidential election (Benkler et al.’s Network Propaganda; Woolley and Howard), Chinese government also uses official accounts in order to promote its ideals.

Our research aims to highlight what devices new propagandistic social media accounts use in order to reach their intended audience. We will focus on Chinese Communist Youth League, since it is a branch of Communist Party of China for people between ages 14-20.

The reason we chose to focus on Chinese Communist Youth League or Youth League is due to their intended younger audience that has distinctly different ways of interacting online compared. Youth League is also quite prominent across different Chinese social media, as they exemplify what other state institutions are trying to accomplish and, in general, do within the digital sphere.

In order to look at the way they achieve their intended goals we will first present an overview of Youth League’s presence on social media to highlight how spread out they are on Chinese Internet. As a further focus of study, through interface analysis we will look at their particular presence on Bilibili and how its affordances, platform design and vernaculars differ from counterparts in the West, as well as how Youth League makes use of them. Through data visualisation, we will focus on the unique Bilibili’s affordance and Youth League’s interaction with it.

Figure 1: Map of Chinese Communist Youth League Social Media Presence

Each bubble constitutes Youth League’s account statistics on different platforms. We also seized them in order to represent their influence on one given platform. Chinese Communist Youth League primarily posts content related to the party’s ideals. The content’s message stay the same throughout different social media, however, its framing would change in order to suit the platform. Although, all their follower counts are in thousands, if not millions.

On TikTok Youth League presence is rather small compared to other accounts with most popular having over 10M followers. However, on a similar platform Kuaishou (more popular in rural areas of China), their presence is much more significant ,since popular accounts have around 5M-10M followers. They are also present on Quora-like platform, Zhihu, although, it is relatively small platform compared to others. On other platforms such as WeChat and Weibo, which could be said to be equivalents for Facebook and Twitter respectively, Youth League presence is also not that significant. Whereas, on Bilibili their presence is quite prominent, compared to their other social media.

Why Bilibili?

Bilibili presents an interesting case of social video platform. Since its creation around 2009, it is mainly situated in subcultural realm. However, Youth League managed to get a foothold on it, with their account having over 5M followers. Moreover, it possesses some affordances that are quite different from its Western counterparts. The combination of the two aspects make it a model example of how Youth League uses social media platforms and how successful it is.

BiliBili

Bilibili is one of China’s biggest video-sharing sites, as well as the country’s biggest anime streaming site (Abacus). It has 110.4 million average monthly active users with 6.3 million paying for their subscription in 2019, according to its financial report for the second quarter. Most users of Bilibili are students or young graduates who are categorized as “China’s Generation Z”, who is considered to be more susceptible to be influenced by the outer society. As the data showed (see figure 2), about 68 percent of its users are from the age groups between 0-24, which correspondingly includes Youth League’s target group (Guo). Accordingly, this website provides a compatible target group to the Youth League’s propaganda project on social media.

Meanwhile, specific characteristics and affordances of Bilibili as a social media platform also make contributions to the Youth League’s success on it. Since it is not anymore only a video-watching website offering illegal Japanese anime as when it first started out in 2009 (Abacus); instead, over the development of 10 years Bilibili expanded into a diverse platform with abundant video sections devoted to music, life, entertainment and so on. Although it still follows the original structure and format of certain features, such as “bullet comments” and the focus on ACG (anime, comics and gaming) content, borrowing from the pioneered Japanese video site Niconico. However, the fast increasing user number requires the update of creative affordances. With the introduction of new features such as social newsfeed, mobile gaming, e-commerce and improving active interface, users of Bilibili have gradually being drawn into the platform with a high degree of engagement and enjoyment (Parklu).

Figure 3: Bullet Comment

There are two key affordances we should highlight here. Aiming at understanding “the new dynamics or types of communicative practices and social interactions” those two features afford (Bucher and Helmond 12), we try to provide a lens of how Youth League take advantage of such dynamic for its own benefits and propaganda. Firstly, Bilibili creates an open environment for users to produce their own contents. “The platform is enriched by over 730,000 original content curators who submit 2.08 million indigenous videos accounting for 89 percent of the total videos being played” (He 2019). Besides, the feature of “danmu” (Bullet Comments) borrowed from Niconico also attracts users’ attention. Basically, Bullet comments (see figure 3) are one-line comments contributed by viewers that float directly above the video you are watching; it can either be in real-time or comments left by previous viewers pegged to specific moments in a video (Abacus). Using the bullet comments, Bilibili “standardised a mode of engagement across its service and affected perceived range of possible actions linked to its feature” (Bucher and Helmond 13). Users can share their feelings instantly and have synchronized interactions with their online neighbours, which assist in generating a sense of belonging within the particular subcultural community. Thus, features such as original production and bullet comments are endowed with different “meanings, feelings, imaginings and expectations” (Bucher 480) by their creators which reveal a vibrant online environment cultivated by the platform and its different actors.

Any social media platform has its underlying logic of “connectivity” which fosters the “interaction behaviour” within it. Since “propaganda works to influence the opinions and actions of individuals in society based on emotional appeals, rather than rationality” (Bolsover 8), in the case of Bilibili, “the emotional interaction” and “high degree of engagement” of the platform makes it one of the base grounds for Youth League and the Party to conduct their propaganda on young minds. Normally, “social media platforms can be characterized as digital intermediaries that draw together and negotiate between different actors such as end-users, developers and advertisers which each come with their own aims and agendas” (Bucher and Helmond 15), here, political elements are directly embedded within the intermediation of platform.

In 2016, the Communist Youth League of China opened account on the platform aimed at promoting patriotism among young people (Sun). With the operation and growth in recent years, the authorities have joined the game of Bilibili in a powerful and effective way. On the one hand, the authorities use affordances and active environment of platform to close the distance between them and citizens and diminish the seriousness of politics in Chinese context, on the other hand, the action of platforms is also under the influence and surveillance of government and political system. To stay on the party’s good side, Bilibili now plays host to a wide suite of content produced by Chinese Department of Propaganda, not only changing the interface design such as the banner, or plan the unique project for national interest (see Figure 4 and 5), but also compelled to occasionally shut down streaming of what the government considers “morally unsound” material (He 2019). This transformation effectively helps the development of political contents and benefits it in becoming more and more mainstream within the platform, while widely and subtly promoting patriotism and Chinese version of political correctness. The Youth League is one of the important cases in this intermediation.

Youth League on Bilibili

Based on Bilibili’s huge amount of users’ groups and the embedded feature of on-screen comments, this subcultural media is repurposed by Chinese Communist Youth League into a significant platform for propaganda to thrive. Comparing with the conventional intense propaganda, the League plays an active role in producing patriotic content in a soft way to interact with Chinese young generation. Chinese Communist Youth League owns over 5 million audience has published more than 2 thousand videos and its content was viewed nearly 700 million times (Bilibili). Taking advantage of dominant themes of this subcultural platform, the League creates videos which expressing political issues and national events in a vernacular way. It attempts to enable official discourse to meet and mix with online pop culture. This tactic is used to generate an impression to youth that Chinese political authorities could communicate with young people electronically and they could speak the same language with youth. According to Lasswell, he thought propaganda is the control of opinion realized by significant symbols or concrete discourse (165). However, this direct form of propaganda is no longer applicable in social media era because it is not sufficient to raise the sense of empathy with content among Internet users. In this way, the League make its patriotic outputs to be expressed in a less serious, acceptable and seducing way for young Chinese to engage with.

To influence on young users’ daily debates, Youth League combines its patriotic education with Bilibili’s platform vernaculars to make it feasible to approach to young people. Gibbs et al., suggested that “social media platform comes to have its own unique combination of styles, grammars and logics, which can be considered as constituting a ‘platform vernacular’ or a popular genre of communication” (257). This form of communication derives from particular user habits and their ways to interact with platforms. Users developed distinctive ways through specific phrases and jokes to have their own language and social norms native Bilibili. Youth League integrates into this atmosphere to break the boundaries between authorities and the younger generation by placing its propaganda content in vernacular subcultural forms. For example, it published a cartoon series named Year Hare Affair, in which it used different animals to represent countries, in order to retell the politically correct historical truth. In addition, CCYL created meme videos to express their opinions towards political issues. For instance, there is a meme video talking about Hong Kong black terror in a ridiculous and sarcastic context. Moreover, the League is also engaging in entertaining ways. For instance, it cooperates with an underground hip-hop group to produce a music clip named This Is Our Generation which express the pride to be a Chinese by folkloric lyrics (Figure 6). These strategies are related to Philips and Milner’s idea of vernacular expression which is “fundamentally hybrid, handily blurring the lines between structure and play, formal and folk, commercial and populist” (21). By applying the specific youth vernacular expressions to political discourses, the League tries to build a credible image to show it takes the same stand with young Chinese.

Data analysis and visualization

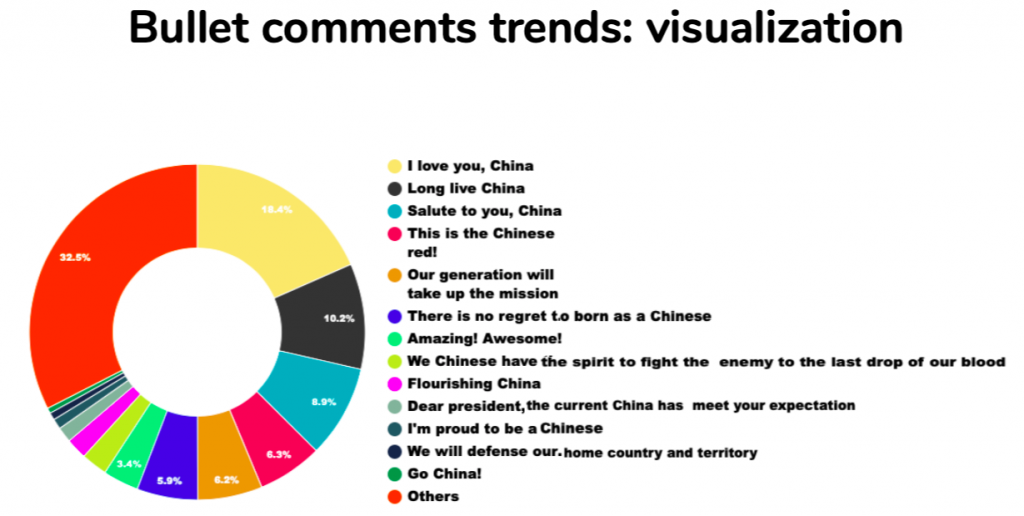

After observing the tactics taken by Chinese Communist Youth League for propaganda, we use visualization of data and comparison to analyze to what extent, CCYL could have a high engagement rates with young audience in patriotic practices on Bilibili. Bullet comments from popular videos published by CCYL has been collected to identify trends of young audience’s opinions. We picked up four vernacular videos as samples of different categories, which are about military parade, stories of communist party, public speech and historical issues (Figure7). The extraction of bullet comments was realized by a Chinese crawler named Jijidown, which could help to download all enabled on-screen comments into plain text. Then, keywords ranking tool was employed to calculate the frequency with which similar comments appear. In view of the translation issue, words with similar meanings are allocated to the same category. There are 175780 bullet comments in total for these four videos. But due to the platform design, only the latest 3500 bullet comments are shown and could be extracted. These available comments are ranked by frequency in a table (Figure 8). Moreover, these statistics are visualised in a pie chart to show audience’s keywords (Figure 9). What can be seen from the table and the piechart is that 13 particular keywords appear in bullet comments with a high frequency. For example, “I love you China” is ranked on the top and was commented 644 times out of 3500, which account for 18.4%. And it is followed by expressions of “Long Live China”, “Salute to you China” and others. All these 13 trending comments are in highly positive and patriotic forms and account for a large percentage of the total. Besides, the category “Other” accounting for 32.51% percentage of the comments includes other single and less frequent expressions. However, there is a noticeable trend that these “Other” comments all have positive or neutral connotation with rare negative comments that appear on screen.

Figure 9. Pie Chart: Bullet (on-screen) comments trends

However, there are some limitations in our analysis. Due to the large scale of censorship practices on Chinese social media, spam and politically sensitive terms would be monitored and suppressed for governance of society (Bamman et al. 2012). Bullet comments of CCYL’s videos are filled by positive points to a large extent, whereas it is difficult to see negative components or objections among data collected in this project. But these data results still could provide valuable insights into how Youth League successful in conducting propaganda campaigns on the social media platform with a large amount of young audience who are appealed to follow the League’s guidance. To measure the efficiency of propaganda campaign Bilibili, a comparison was made with its TikTok account. In general, Youth League also publishes patriotic video to interact with users of TikTok. However, from the statistics, there are less engagement from young people on TikTok compared to Bilibili. For the videos which have been liked more than 100 thousand times, there are only a few hundred comments expressing their ideas (Figure 10).Compared to the huge amount of interactive comments on Bilibili, other social media, such as TikTok, are less sufficient to engage young people.

These data could support an argument that some Chinese young audience’s patriotic passion has been aroused to a large extent. And the effect of these passionate comments appearing along with video content could reinforce the impression by an integrated effect. Through spreading this form of soft persuasion and producing widely vernacular content on this youth-oriented platform, Chinese Communist League construct a tight-knit community within which it could promote propaganda in the interaction with users.

Conclusion

Communist Youth League of China prominent presence on various social media serves as an example of a “tool to monitor public opinion and allowing an efficient distribution mechanism or state entities” (Computational Propaganda in China). Since the traditional way of propaganda do not translate well into social media realm, thus, from the example of Youth League we can see how official institutions adapted and incorporated vernaculars into propagandistic discourse.

From the example of Bilibili, we could see how Youth League uses existing platform affordances, as well as shaping additional ones in order to promote its and other Chinese politically correct content even further. It effectively uses very similar techniques used by marketers today online and is quite successful in this endeavour. Moreover, bullet comments as an affordance create elevated engagement and emotional interaction, which fits into propagandistic tool kit, since it aims to incite sentimental response rather than rational one.

References:

“Bilibili- Chinese Communist Youth League”. Space.Bilibili.Com, 2019, https://space.bilibili.com/20165629?spm_id_from=333.788.b_765f7570696e666f.1. Accessed 22 Oct 2019

Abacus. “Bilibili, China’s biggest anime site, covers the screen in user comments.” [online] South China Morning Post. 2019. Available at: https://www.scmp.com/tech/big-tech/article/3028230/bilibili-chinas-biggest-anime-site-covers-screen-user-comments [Accessed 22 Oct. 2019].

Bamman, David et al. “Censorship And Deletion Practices In Chinese Social Media”. Journals.Uic.Edu, 2019, http://journals.uic.edu/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/3943/3169. Accessed 21 Oct 2019

Benkler, Yochai, Robert Faris, and Hal Roberts. Network Propaganda: Manipulation, Disinformation, and Radicalization in American Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2018

Bilibili. “Bilibili Inc. Announces Second Quarter 2019 Financial Results”. [online] GlobeNewswire News Room. 2019. Available at: https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2019/08/26/1906790/0/en/Bilibili-Inc-Announces-Second-Quarter-2019-Financial-Results.html [Accessed 22 Oct. 2019].

Bucher, Taina, and Anne Helmond. “The Affordances of Social Media Platforms.” In The SAGE Handbook of Social Media, edited by Jean Burgess, Thomas Poell, and Alice Marwick. 2017, London and New York: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Bucher, Taina. “The Friendship Assemblage: Investigating Programmed Sociality on Facebook.” Television & New Media, vol. 14, no. 6, Nov. 2013, pp. 479–493, doi:10.1177/1527476412452800.

Gillian Bolsover, “Computational Propaganda in China: An Alternative Model of a Widespread Practice.” Samuel Woolley and Philip N. Howard, Eds. Working Paper 2017.2. Oxford, UK: Project on Computational Propaganda. comprop.oii.ox.ac.uk<http://comprop.oii.ox.ac.uk/>. 32 pp.

Guo, Diandian. “Chinese Communist Youth League Joins Bilibili – Where Official Discourse Meets Online Subculture”. Whatsonweibo.Com, 2017, https://www.whatsonweibo.com/chinese-communist-youth-league-joins-bilibili-official-discourse-meets-online-subculture/. Accessed 20 Oct 2019

He, Laura. “China’s ban on foreign video content is not about piracy.” [online] South China Morning Post. 2019. Available at: https://www.scmp.com/business/companies/article/2102948/chinas-ban-foreign-content-bilibili-acfun-not-about-piracy [Accessed 22 Oct. 2019].

He, Wei. “Bilibili carves a niche with synchronized online interactions” [online] Chinadaily.com.cn. 2019. Available at: http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/global/2019-07/12/content_37490778.htm [Accessed 22 Oct. 2019].

Lasswell, Harold D, and Arnold Austin Rogow. Politics, Personality, And Social Science In The Twentieth Century. University Of Chicago Press, 1969.

Li, Lihong. “Youth League should take advantage of social media and pop culture.” [online] The China Youth Daily. 2009. Available at: http://www.gqt.org.cn/newscenter/tendency/200908/t20090821_284325.htm

Martin, Gibbs et al. (2015) “#Funeral and Instagram: death, social media, and platform vernacular”. Information, Communication & Society, 18:3, 2015: 255-268, DOI: 10.1080/1369118X.2014.987152

Parklu. “Why Brands Should Not Overlook Bilibili to Target China’s Gen-Z”. [online] Luxury Society. 2019. Available at: https://www.luxurysociety.com/en/articles/2019/07/targeting-chinas-generation-z-cool-kids-are-bilibili/ [Accessed 22 Oct. 2019].

Phillips, Whitney, and Ryan M. Milner. The ambivalent Internet: Mischief, oddity, and antagonism online. New York: Polity, 2017

Samantha Bradshaw & Philip N. Howard. (2019) The Global Disinformation Disorder: 2019 Global Inventory of Organised Social Media Manipulation. Working Paper 2019.2. Oxford, UK: Project on Computational Propaganda.

Sun, Wanning. “Chinese propaganda goes tech-savvy to reach a new generation.” [online] The Conversation. 2019. Available at: https://theconversation.com/chinese-propaganda-goes-tech-savvy-to-reach-a-new-generation-119642 [Accessed 22 Oct. 2019].

Figures

Figure 1: Map of Chinese Communist Youth League Social Media Presence. Made by Anna

Figure 2: Age Group of Bilibili Users. Source: 36ker.com Accessed 23 October 2019

Figure 3: Bullet Comment. Source: South China Morning Post.com. Accessed 23 October 2019

Figure 4: The Design of Bilibili’s Homepage Celebrating China’s 70th National Birthday. Source: Bilibili.com. Accessed 23 October 2019.

Figure 5: Special Project Celebrating China’s 70th National Birthday. Source: Bilibili.com. Accessed 23 October 2019.

Figure 6: Chinese Communist Youth League Told Political Issues in Vernacular Forms. Source: Bilibili.com. Accessed 20 October 2019.

Year Hare Affair: Source: https://www.bilibili.com/video/av68289286?from=search&seid=6354115834337733794

Hong Kong black terror: Source: https://www.bilibili.com/video/av70762287

This is our generation: Source: https://www.bilibili.com/video/av7791270

Figure 7: Four videos picked up for keywords ranking of on-screen comments. Source: Bilibili.com. Accessed 21 October 2019.

Review of China 70th Anniversary Military Parade: Source: https://www.bilibili.com/video/av69625456/?spm_id_from=333.788.videocard.0

Hi! This Is Communist Party of China: Source: https://www.bilibili.com/video/av57423406?from=search&seid=694515409735509799

The Speech of Ministry of National Defense of the PRC: Source: https://www.bilibili.com/video/av9643155?from=search&seid=694515409735509799

The memory of martyrs and the hope for the future: Source: https://www.bilibili.com/video/av32705017?from=search&seid=694515409735509799

Figure 8: Table: Bullet (on-screen) comments trends. Made by Xiaoxuan Ma.

Figure 9: Pie Chart: Bullet (on-screen) comments trends. Made by Xiaoxuan Ma.

Figure 10: Chinese Youth League’s videos on TikTok. Source: TikTok. Accessed 21 October 2019.