Dirty Greenwashing: How two apps cash in on the conscious consumer trend

Hashtags like #cleanbeauty, #nontoxicskincare and #greenbeautyproducts are circling popular social media platforms, displaying a recent development of the beauty industry towards cleaner, more ethical products.

Rooted in consumers’ “frustration over regulatory oversight of cosmetics and personal care products” (Wanner and Nathan), the clean cosmetics movement opens up new opportunities for both established and emerging skincare brands to position themselves in a growing market that “is no longer a niche” (Pearson). According to Grand View Research, this trend is here to stay, being projected to become a 25 billion USD market by 2025 (Organic Personal Care Market Size).

This goes to show that like all industries, the organic beauty market is built on profit, with the only difference being a new level of consciousness and critical questioning from the consumer side. A consciousness that, above all, calls for regulations, credibility and transparency. Meeting these standards is, nevertheless, easier said than done. While both the United States and the European Union set a framework of binding chemical and cosmetics regulations (U.S. and EU Cosmetics Regulation), there are grey areas that complicate the matter.

EU regulations, for one, ultimately place the responsibility for the safety of a cosmetic product in the hands of manufacturers, refraining from “an extensive pre-marketing notification/authorisation procedure involving a full toxicological dossier on the ingredients and the finished cosmetic product” (Vera and Pauwels). Even more concerning, the US has only outlawed eleven chemicals as it is (Milman) and exempted ingredients used in cosmetics from the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act passed by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), leaving their citizens’ health to the Personal Care Products Council, a “self-regulating body supported by the cosmetics industry” (Wanner and Nathan). This gap in the system has, however, not gone unnoticed, steering clean beauty apps to step in and provide conscious consumers with detailed ingredient lists and help them “identify the potential risk associated with personal care products” through internal value systems rating products “good” or “bad” in terms of toxicity and allergenicity (Think Dirty Methodology).

With this in mind, we are interested in analyzing said apps in terms of the information provided and user journey presented on their platforms. How does the user experience differ from one app to another and how is the information given framed and translated into authority and legitimacy? To answer this question, we will analyze and compare the interface and Terms of Service of two of the most popular clean beauty apps – Think Dirty and Cosmethics.

Both Think Dirty and Cosmethics are female-founded companies that originate in cancer research and a lack of regulations in the cosmetics industry (A Message from the Founder; CosmEthics | About Us). Their free apps allow users to scan products for their ingredients, add information on uncatalogued items, shop them through the system (Think Dirty has an in-app-shopping option, Cosmethics links to third-party websites) and offer partnership opportunities for brands. Furthermore, they are both privately held companies that have received funding from internationally recognised organisations – Think Dirty was funded by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Council of Canada and Cosmethics is co-funded by the Horizon 2020 programme of the European Union. Think Dirty currently lists over one million products, whereas Cosmethics carries around 130 thousand. The only major difference between the two is that Think Dirty is a US-based and Cosmetics an EU-based company. They are still both internationally available and usable.

To gain further insights into the affordances of both apps and ultimately answer the research-leading questions, we will, firstly, establish a connection to current new media debates. Secondly, we will apply Light et al.’s walkthrough method and do a close reading of the terms of services. Lastly, we will provide a summary of the most relevant outcomes of our analyses and mention limitations and possible junctions for further research into clean beauty apps will round off our examination.

The relevance of clean beauty apps

If you are not willing to spend much time researching products before purchasing but you live in the European Union you can rest assured that, to some extent, the EU and US imposed laws that prevent you from buying anything that poses danger to your health. If you are, however, more interested in the exact ingredients of the products you are buying and identify yourself as a conscious consumer then you are a part of a growing trend. And as a conscious consumer you are expected to make informed decisions when purchasing a product.

To better understand the ingredients of cosmetics and their impact on your health, you might turn to alleged experts in the field: Internet bloggers. Thanks to the green movement, there are a variety of websites where these experts share their opinion on the benefits products. Beauty blogs, where influencers share their experience with readers are booming and bringing considerable profit to the featured brands (Zeldes). Spending your time online reading reviews on products does, however, not always come in handy when you are standing in a store, making a decision between two competing products. Here, clean beauty apps with scanning systems offer a time-efficient, and practical solution as they immediately show ingredient lists and further insights into their toxicity levels.

In doing so, they stand in accordance with the concept of communicative affordances that was introduced by Ian Hutchby and “emphasises how affordances are both functional and relational” (Bucher and Helmond 10). The concept explains that, what a medium affords is related to the communicative practices and habits introduced by them. In the case of clean beauty apps that means that they have arisen from a need to fill a void in the EU and US cosmetics regulations system and to do so in a consumer-friendly, time-saving manner and allow steer consumers to make more conscious decisions. It also aligns with the mobile media affordances, portability, availability and multimediality (Schrock).

Still, with the immediacy of these apps, arises the question of the reliability of their given information, adding to recent criticism of mental health services apps that express false authority over people’s well-being (Pearson). That being said, our study presents an interesting example of the impact of technology on communicative practices (Bucher and Helmond) and, more precisely, shows how apps profit from social movements. It generally contributes a further understanding of affordances and interface designs of new media applications, as well as said debates around authority and legitimacy.

In order to display the user journey presented by the chosen app and answer the question of the authority and legitimacy issues surrounding them, we will apply two methods on two different parts of the apps. First, we will go through some user scenarios, following Light et al.’s walkthrough method, to establish “a foundational corpus of data upon which can be built a more detailed analysis of an apps’s intended purpose, embedded cultural meanings and implied ideal users and uses” (Light et al. 1). Then, we will do a close reading of the terms of services for both apps to observe the information framing and to be able to draw conclusions regarding the authority issue.

The product scanning will be the central focus of the walkthrough, as it represents the central functionality of the apps. Considering Light et al.’s environment of expected use, as well as socioeconomic and cultural aspects (9), we argue that these apps are used by certain types of users in two types of environments – at home, checking already owned products and in stores, for prospective purchases. Thus, we will create one scenario implying the user scanning a product which is found in the app and checking the ingredients and another, following the same scanning mechanism for an uncatalogued item, keeping in mind that affordances “set limits on what is possible to do with, around or via the artefact” (Schrock 1230).

Technical walkthrough

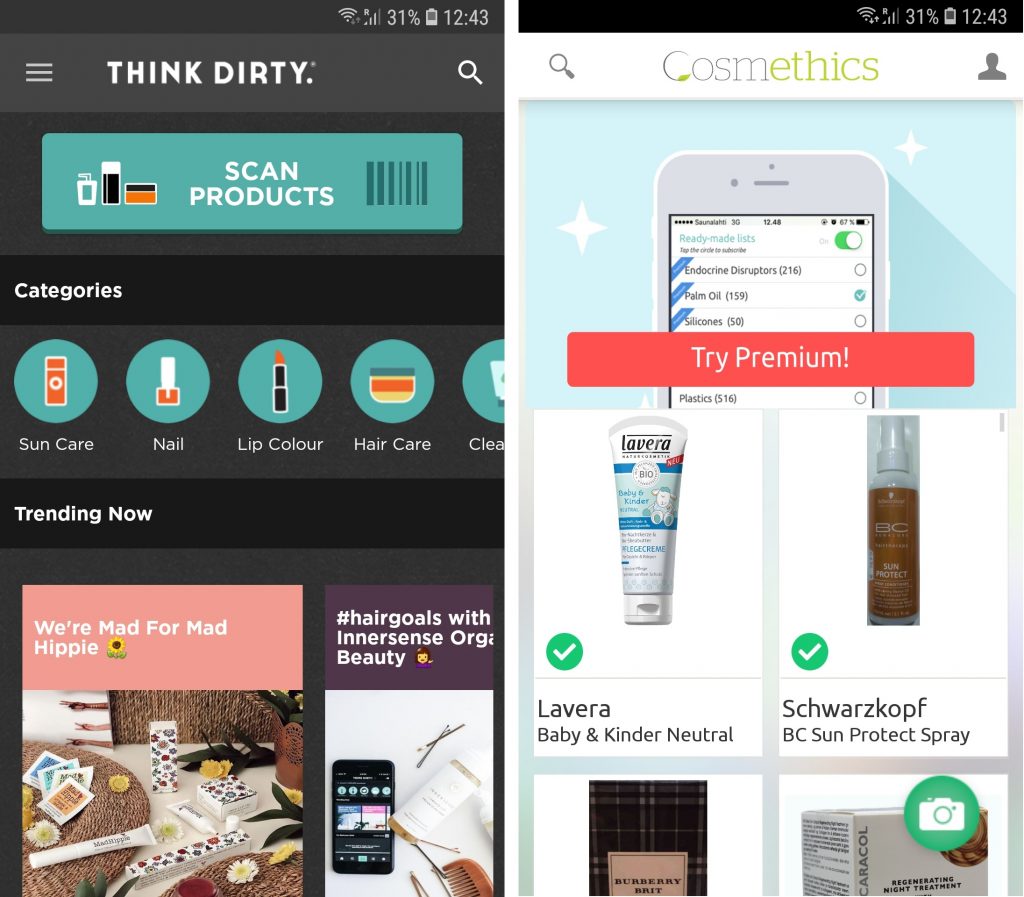

After registration, in Think Dirty (TD), the user is greeted with the dashboard, where the “scan” button is placed right at the top of the page, whereas for Cosmethics (CE) the scan button is rather hidden, with the dashboard being cluttered if the user does not have premium access (fig. 1). Working with Davis and Chouinard’s conceptualization of affordances as requesting, demanding, allowing, encouraging, discouraging and refusing (242) certain built-in practices of the artifact, the walkthrough unravels a clearer version of the apps’ operating model.

While both apps allow scanning and searching, Think Dirty nudges users into scanning, while Cosmethics seems to encourage the user to scroll through the products listed in the dashboard. Following Yeung, we understand nudging as a “deceptively simple design-based mechanism of influence” that the apps rely on to guide users in the developer’s preferred direction in “subtle, unobtrusive, yet extraordinarily powerful” ways (119).

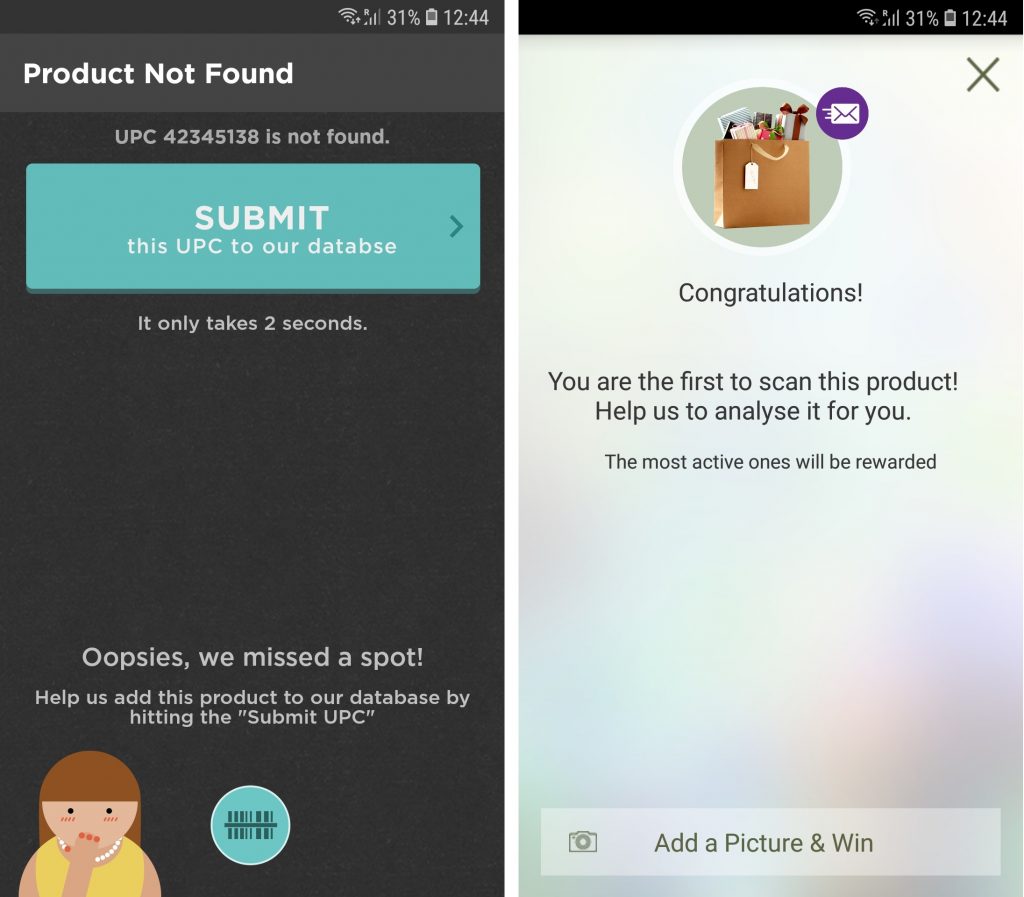

In the case of both apps, scanning an uncatalogued product prompts the user with the following screens (fig. 2):

While both apps have user incentives regarding adding a product, TD actually materializes that by offering collectible badges, whereas CE presents the possibility of “winning”.

After adding the product, CE encourages the user to go to their Facebook page (which is not hyperlinked, even though one might think it is). However, there does not seem to be any mention of this in any post made in 2019.

The actual process of adding a product is rather cumbersome on TD: you have to add multiple photos, select categories (which is a huge list that also has duplicates in it) and add the ingredients and description of the product, so it most certainly does not “only take 2 seconds”.

Whereas CE has simplified this process to just taking pictures of the front and back of the product. What is interesting is the fact that the app mentions there will be a “manual ingredient safety check”, which we will talk about later. But what if the product has already been added to the app? Both apps take the user directly to the product screen.

Both apps afford expected behaviors, such as adding it to a list or sharing it. However, one feature that differs across apps is the “Shop” button. While TD highlights it with a blue color at the top of the screen, encouraging users to press it, CE’s button is labeled as “Visit Store Site” and does not stand out from the other options. This poses questions regarding the objectivity of TD through how this might influence certain products in favor of others.

What stands out in CE is the presence of a “recommended non-toxic” feature, claim which will be discussed in the next section.

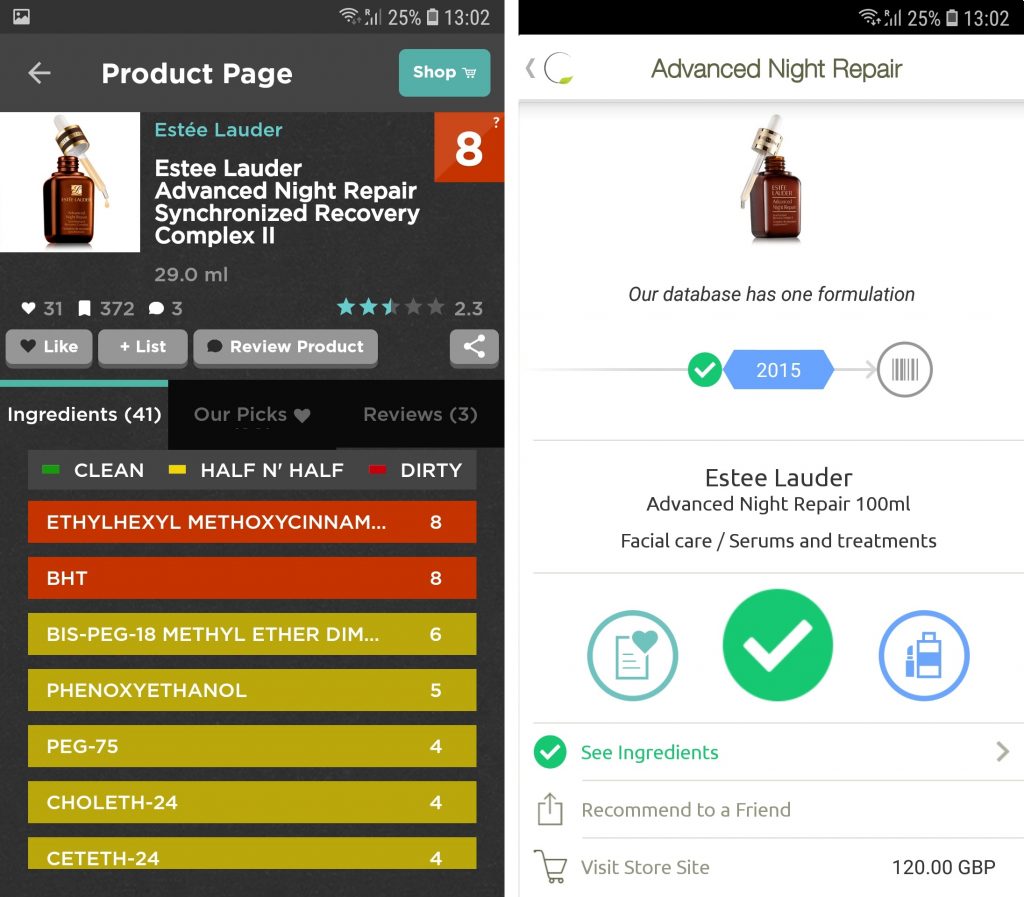

The representation of ingredients is where the apps radically differ. If TD has them sorted from harmful to safe, with an appropriate color coding – thus, the user is expected to take the information at face value, as reading long texts in the app’s tiny frame is uninviting – CE basically just lists ingredients and only lets the user know if they are potentially harmful. Still, there is no color coding, which means that the structure of authority is much more subtle: as long as the product has a green tick, you are good to go.

Close reading of Terms of Service

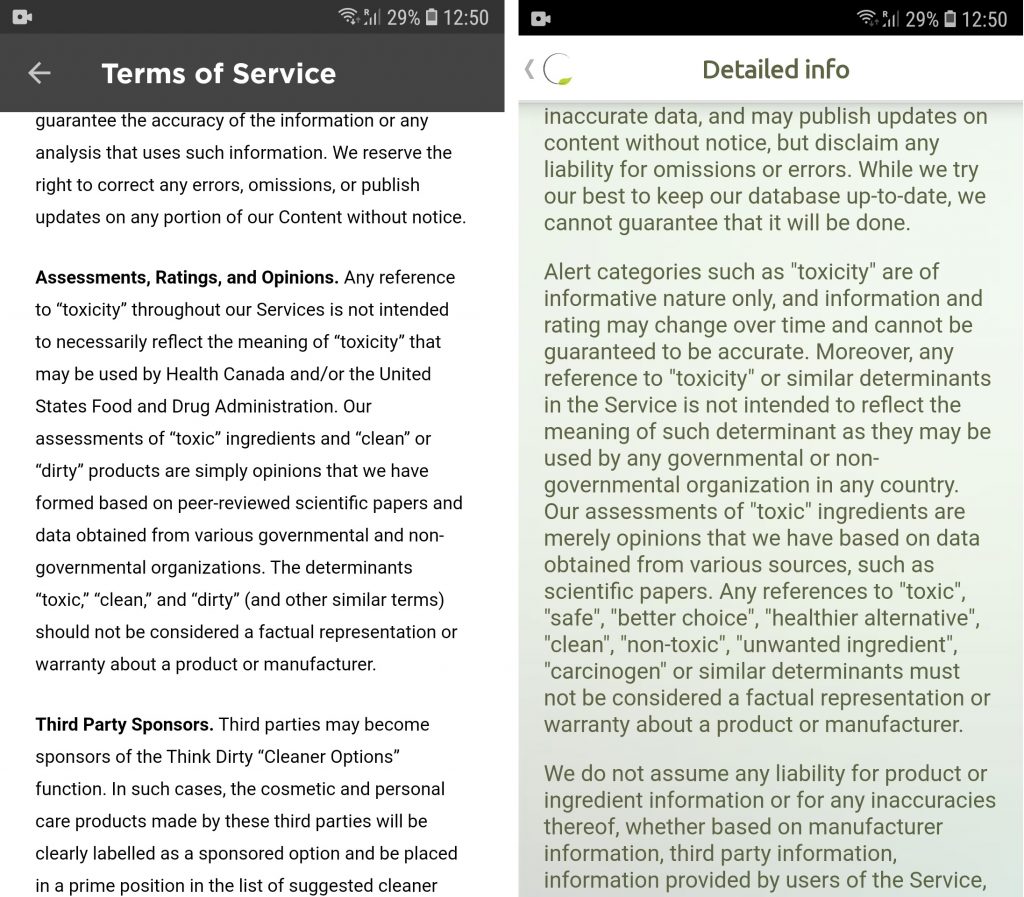

The user journey alone does not offer the whole picture of the apps’ vision, but rather showcases how they desire to be perceived. The Terms of Service sections allow us to go deeper into how the apps position themselves in regard to authority. Platforms like these seem to hide more than they reveal in their endeavor to “sell, convince, persuade, protect, triumph or condemn” what should be expected of them (Gillespie 359), which makes us frown upon their objectivity claims. In this regard, we looked at how the apps relate to “toxicity” (fig. 3) – a term that is crucial ingredient-wise.

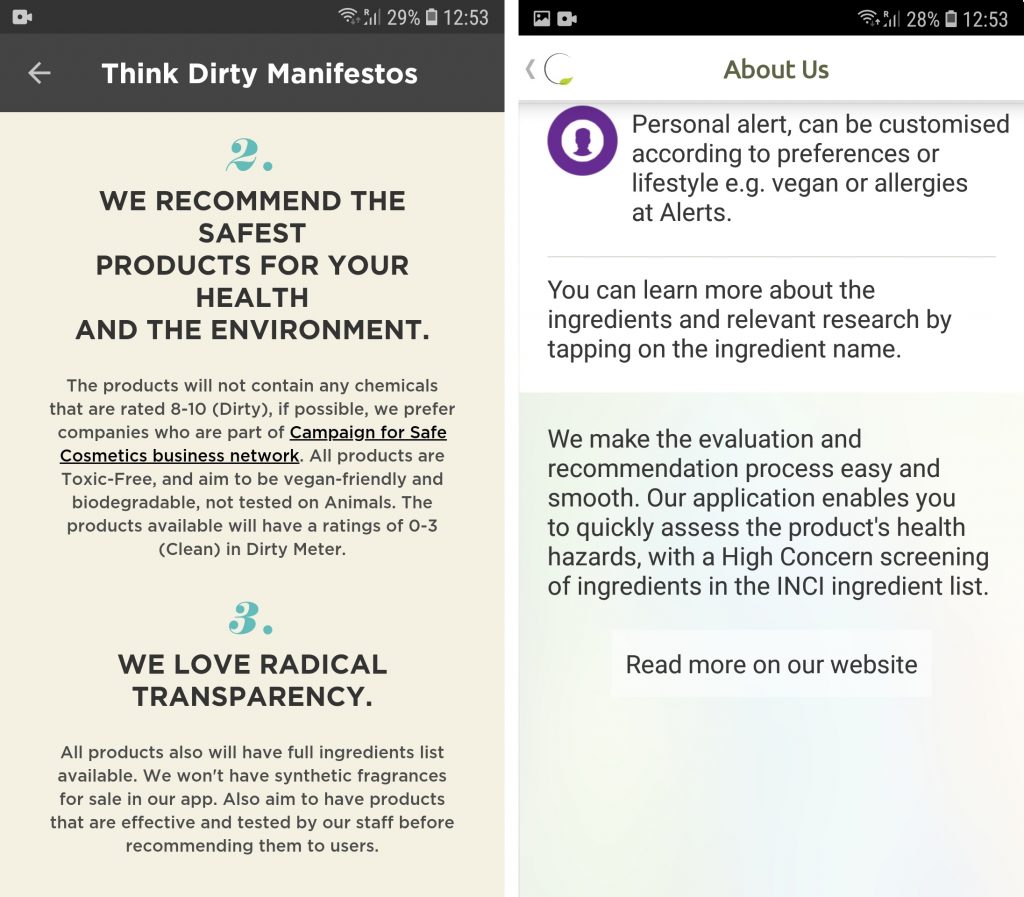

Apparently, both apps distance themselves from making claims on a product’s toxicity, placing the authority on specific legislations. It seems that the key words hold little value, as they should not be seen as an absolute truth. This, of course, shakes the core purpose of the apps – to be able to help you distinguish between “toxic” and “safe” products. Both apps mention that they are not a substitute for professional healthcare advice, yet their respective “About us” sections could indicate the contrary (fig. 4).

An example of how their “good” and “bad” ingredient ideas clash is represented by this product (fig. 5).

Moreover, these apps try to portray data framing by following the data-information-knowledge-wisdom pyramid, giving the user valid and reliable information (Kitchin) on their products to ensure transparency. However, the Terms of Service clearly advise the users otherwise, which defeats the point of downloading the app in the first place. Both apps claim that the information regarding the products is crowdsourced, or directly provided by the brands themselves (Think DirtyTM – TERMS OF SERVICE; Cosmethics Terms of Service) – which, again, casts a shadow of doubt over their legitimacy.

What are, thus, the evaluations of Think Dirty’s Founder and Advisory Board and Cosmethics’ assessments worth? Are they meant to guide you to choose clean products, as the apps’ interface suggests, or are the claims lost in terms of services?

Conclusion, limitations and further research

As our research shows, the question of how the user journeys are presented by two clean beauty apps and where their similarities and differences lie, can be answered through a closer look at their affordances and interface designs.

While both apps follow the same principle of scanning and listing beauty products and thereby aim to make their users more aware of product ingredients and possible toxins, they differ in the focus of their preferred outcome. Think Dirty nudges users to scan items, whereas Cosmethics encourages them to scroll through product lists in the dashboard. Yet, the process of adding information on uncatalogued products to the TD database is more time-consuming and complicated, compared to CE. Differences between the apps also become apparent in regards to shopping already listed products. In contrast to CE, that does not give its “Visit Store Site” special attention, TD draws highlights their “Shop” button through noticeable color priming. Again, this puts an emphasis on the underlying focus on profit-making in the clean beauty industry (Pearson)– TD directly profits from their in-app shopping links, while CE solely offers it as a service to their users (A Message from the Founder; CosmEthics | About Us).

Furthermore, an examination of both the labeling of harmful products within the apps and their self-positioning within the Terms of Service shows that while they use different approaches toward the presentation of product information, they ultimately both refrain from taking responsibility for the information they provide. Both apps clearly state that they cannot substitute professional healthcare and practically delegitimize themselves by stating that their information relies on tertiary data.

Even though our research offers further insights into the affordances of clean beauty apps and underlying legitimacy issues, it shall be mentioned that it is only a small-scale starting point to answer the questions posed. A more thorough investigation into the sources of information used by these apps and a larger sample would have exceeded the framework set by this project, yet would have allowed for additional insights. Moreover, including expert or user interviews alongside the walkthrough and close-reading method could shed light on other related questions regarding the framing of the apps and user perception. Nevertheless, the methodology used within our study and our findings provide a foundation for further research into the intersection of the clean beauty industry, apps and new media debates.

Bibliography

“A Message from the Founder.” Think Dirty, https://www.thinkdirtyapp.com/about/. Accessed 24 Oct. 2019.

Bucher, Taina, and Anne Helmond. “The Affordances of Social Media Platforms.” The SAGE Handbook of Social Media, by Jean Burgess et al., SAGE Publications Ltd, 2018, pp. 233–53. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.4135/9781473984066.n14.

“CosmEthics | About Us.” About Us, https://www.cosmethics.com/aboutus/. Accessed 24 Oct. 2019.

Cosmethics Terms of Service. http://s3.cosmethics.com/general/tos.html. Accessed 23 Oct. 2019.

Davis, Jenny L., and James B. Chouinard. “Theorizing Affordances: From Request to Refuse.” Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society, vol. 36, no. 4, Dec. 2016, pp. 241–48. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1177/0270467617714944.

Gillespie, Tarleton. “The Politics of ‘Platforms.’” New Media & Society, vol. 12, no. 3, May 2010, pp. 347–64. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1177/1461444809342738.

Kitchin, Rob. The Data Revolution. SAGE, 2014.

Light, Ben, et al. “The Walkthrough Method: An Approach to the Study of Apps.” New Media & Society, vol. 20, no. 3, Mar. 2018, pp. 881–900. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1177/1461444816675438.

Milman, Oliver. “US Cosmetics Are Full of Chemicals Banned by Europe – Why?” The Guardian, 22 May 2019. www.theguardian.com, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2019/may/22/chemicals-in-cosmetics-us-restricted-eu.

“Organic Personal Care Market Size Worth $25.11 Billion By 2025.” Grand View Research, https://www.grandviewresearch.com/press-release/global-organic-personal-care-market. Accessed 24 Oct. 2019.

Pearson, Bryan. “Clean Beauty Can Be A Dirty Business: Beautycounter, Sephora And P&G Are Changing That.” Forbes, https://www.forbes.com/sites/bryanpearson/2019/01/21/clean-beauty-can-be-a-dirty-business-beautycounter-sephora-and-pg-are-changing-that/. Accessed 24 Oct. 2019.

Schrock, Andrew Richard. Communicative Affordances of Mobile Media: Portability, Availability, Locatability, and Multimediality. 2015, pp. 1229–1246.

“Think Dirty Methodology.” Think Dirty, //www.thinkdirtyapp.com. Accessed 24 Oct. 2019.

Think DirtyTM – TERMS OF SERVICE. https://www.thinkdirtyapp.com/termsofservice/. Accessed 23 Oct. 2019.

U.S. and EU Cosmetics Regulation | Cosmetics Info. https://cosmeticsinfo.org/cosmetics-regulation. Accessed 24 Oct. 2019.

Vera, Rogiers, and Marleen Pauwels. “Cosmetic Products and Their Current European Regulatory Framework.” Current Problems in Dermatology, vol. 36, 2008, pp. 1–28.

Wanner, Molly, and Neera Nathan. “Clean Cosmetics: The Science behind the Trend.” Harvard Health Blog, 4 Mar. 2019, https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/clean-cosmetics-the-science-behind-the-trend-2019030416066.

Yeung, Karen. “‘Hypernudge’: Big Data as a Mode of Regulation by Design.” Information, Communication & Society, vol. 20, no. 1, Jan. 2017, pp. 118–36. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1080/1369118X.2016.1186713. Zeldes, Rich. New Research Backs Up the Boom in Beauty Influence. https://www.stellarising.com/blog/beauty-influence-boom. Accessed 24 Oct. 2019.