Tinder vs. Bumble: Can You Afford Falling in Love?

From its very beginning, “the Internet has supported social interaction and the search for a soul mate” (Whitty 212). This research explores the dating app phenomenon in-depth, comparing two popular dating apps: Tinder and Bumble. How do Tinder’s affordances differ from feminist daughter Bumble? And how does it relate to current debates on gender and data? This project aims to address the criticism of contemporary dating apps while making use of the walkthrough method as our modus operandi.

Introduction: Online Dating

Online dating is a system where people can look for others and present themselves – over the Internet – to develop a personal, romantic, or sexual relationship. The first digital dating services appearance was in 1959. As a result of a class project, Jim Harvey and Phil Fialer made use of a survey and an IBM 650 – one of the American multinational early computers – to match 49 women and men (Gillmor 74). Thirty-five years later, in 1994, Kiss.com launches the first modern dating website.

At this point, online dating has become an integral part of digital lives. In 2000, eHarmony enters the field and sets the first online dating website for long-term relationships (eHarmony). The age of dating apps starts with Tinder, in 2012, not only being the first one in history, but also the biggest and most widely used this century. Following the app’s success, a number of competing apps have also gained popularity. Created in 2014, Bumble was launched as a “100 percent feminist” app in an attempt to challenge traditional dating norms.

Dating apps’ increasing popularity

Although online dating websites were “once considered taboo”, they are “now a socially accepted and booming multibillion dollar business that continues to grow” (qtd. in Chamourian 4). In 2017, Chamourian found that more than half of single Americans had used online dating services with around 40 percent indicating that they had dated a person they met online. Compare this to only 25 percent of participants indicating that they had met a first date through a friend (Chamourian). Online dating now constitutes one of the most popular ways to meet new people.

Affordances

In order to understand how these dating apps shape and influence modern dating practices, we will be looking at the concept of affordances. Broadly explained, the concept refers to the “range of functions and constraints that an object provides for, and places upon, structurally situated subjects” (Davis and Chouinard 241).

Plainly put, the concept looks at the relationship between users and a piece of technology. Within the context of dating apps, it could ask how design may influence behaviour; how some apps may encourage some activity while discouraging others.

Through the concept of affordances, we connect the dating app “phenomenon” to relevant academic debates, such as the construction of gender, how affordances shape and structure their users’ identities, and issues surrounding data and privacy.

Tinder

Tinder was founded in September 2012 by Jonathan Badeen, Justin Mateen, Joe Munoz, Dinesh Mrjani, Chis Gylczynski, and Whitney Wolfe (Macleod & Mcarthur 824). In order to use the app, ‘users must enable their smartphone’s location tracking and grant the app access to that data’. They can filter who is presented to them by age, gender and distance (Macleod & Mcarthur 824). We have used Tinder version: 11.1.0 in our analysis.

Since dating apps have become a prominent part of media objects of the 21st century. Since the apparition of Tinder on iOS and Android, a high number of scholars have been showing great interest in the smartphone dating app. It is one of the first apps that was not just a smartphone add-on to an online dating website (Sumter et al. 4). Its practical, easy interface, location tracking and swipe method made chatting and messaging relatively simple (MacLeod & McArthur 824). Thus, Tinder is scoring high in popularity with 1.4 billion swipes a day (LeFebvre 1206).

Bumble

However, even though many users enjoy Tinder, it also faces criticism, most significantly by Wolfe, ex-founder of Tinder, and now founder of Bumble, promoting itself as the ‘Anti-Tinder’ app (Bivens & Hoque 443).

Wolfe, who was fired from Tinder in 2014 amid an acrimonous breakup with one of the other founders and sued the company for sexual harassment, founded Bumble in December in 2014 (Yashari). The ideal was for Bumble to stand as a feminist app and to contribute to the change in traditional gender roles found in dating (Bivens & Hoque 442). To do so, Bumble only allows women to talk to men to initiate a conversation, unlike tinder, where both genders can decide to send a message first. Furthermore the ‘heterosexual dating norms’ were meant to be challenged by adding more genders than the binary Tinder offers (Yashari).

A true feminist alternative?

However, users do not seem to fully be transcendent by the feminist stance of the app. For example, users stating that past that first message, norms were being immediately re-attributed (MacLeod & McArthur 827). In fact, many users argued that they thought Tinder was more of a ‘feminist’ app, as it gave equal chances for both gender to start talking to each other (Bivens & Hoque 450).

A criticism that both apps face is their non-distinction between both sex and gender with users expressing emotional distress that they were not represented (Bivens & Hoque). Tinder has also been found to be mostly targeted towards people who identified themselves as heterosexuals, leaving a big chunk of users potentially feeling left out (Timmermans & De Caluwé 74). Thus, concerns were raised in relation to the app’s real stance, wondering if it was actually not limited to a mere marketing plan (Bivens & Hoque 442).

The Walkthrough Method

In order to address these concerns and critically compare Bumble to Tinder, our research group used the Walkthrough Method by new media scholars Light, Burgess and Duguay. This method combines analyzing both cultural and technological aspects through direct engagement with the app’s interface (Light et. al. 2). In doing so, technological mechanisms can be examined and discursive and symbolic representations (Light et al. 4) behind for example the app’s interface can be uncovered.

Environment of expected use

The first step in this method was to establish the ‘Environment of Expected Use’, which consists of the organization’s vision, its operating model and its regulations and restrictions (Light et al. 9-11). This for example includes Bumble’s focus on protecting women and their privacy and data regulations.

Technical walkthrough

Following, was the technical walkthrough. Our research group downloaded both Tinder and Bumble and screenshotted our every interaction with the application throughout multiple days. During these days we analyzed the differences in the user interface arrangement, the specific functions and its features, the textual content and tone, and the symbolic representation in the registration and entry, the everyday use and the app suspension, closure and leaving (Light et al.).

Registration and entry

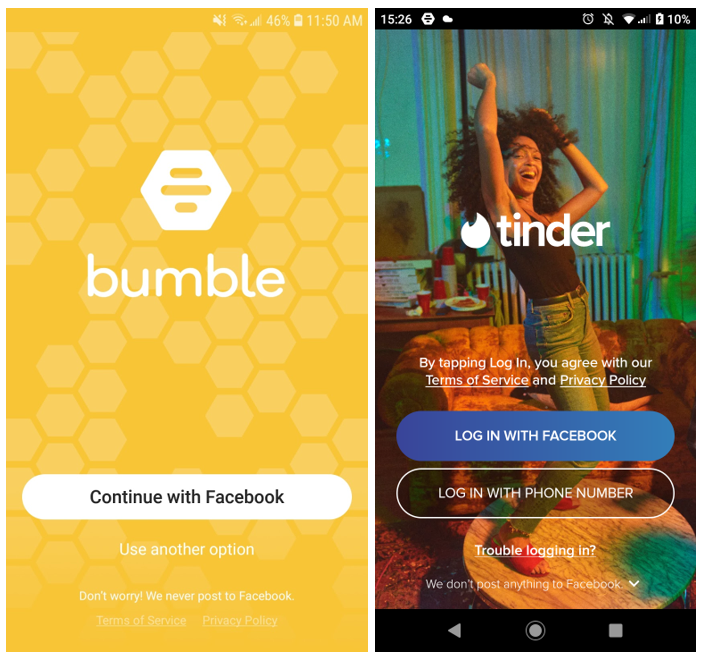

We started by downloading the app’s individually in our app stores, after which we set up an account. Both Tinder and Bumble gave us the option to either log in with Facebook, or email. Some of us did so on Facebook, which gave the comfort of being able to choose an already selected picture and synchronize certain information.

For the purpose of this demonstration, for both of the apps, our team chose to ‘Use another option’ and ‘Log in with phone number,’ respectively.

Following this selection, a phone number verification, email address, and inputting date of birth, we were asked to ‘build the profile.’ Both apps required us to upload a photo. While Bumble outlined that the photo should be of the user and not include other people. To contrast, Tinder laid out no guidelines.

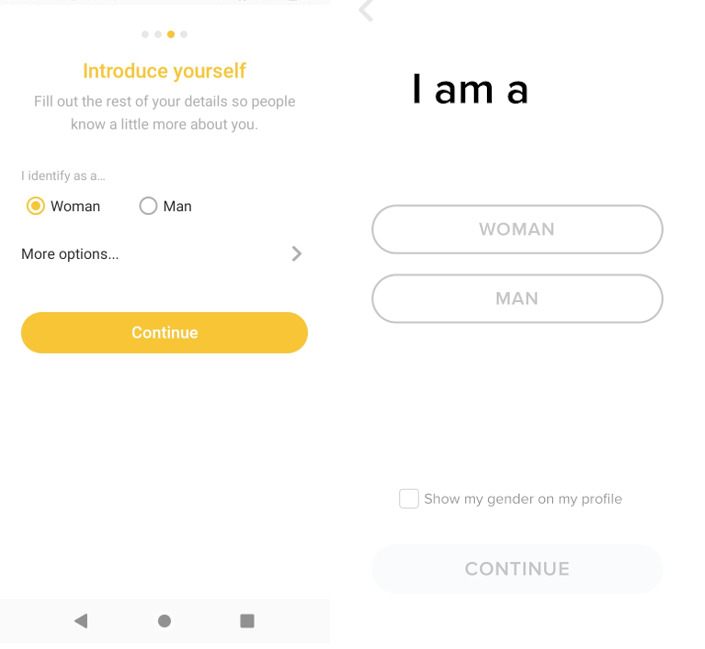

Next, we were asked to ‘Introduce’ ourselves. When setting up an account for Bumble, one could choose from an impressive list of genders, whereas Tinder only provided the option to choose from two genders.

Similarly, in regards to sexuality, Bumble asked whether we were interested in Men, Women, or Everyone. Tinder, however, did not provide the option and assumed we were seeking a heterosexual relationship.

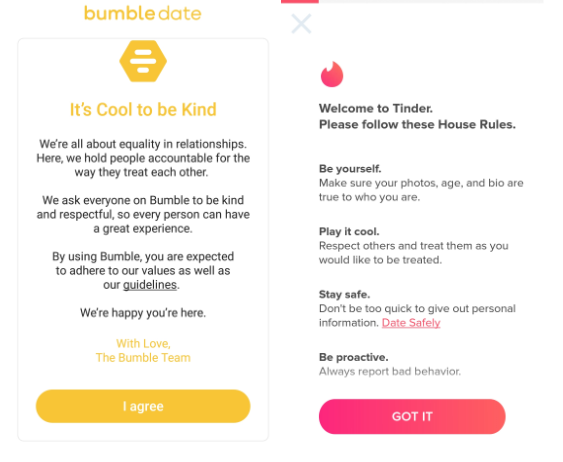

Lastly, before we started swiping, both applications required us to consent to both their respective guidelines and location tracking.

Get to swiping!

While it was not required to participate, within the respective apps, both encouraged us to include more information to boost our chances of matching. While it was incorporated in both apps, Bumble’s is more extensive. Bumble’s profile setting included a list with questions about height, job title, drinking and gym habits, education level, etc.

Matching

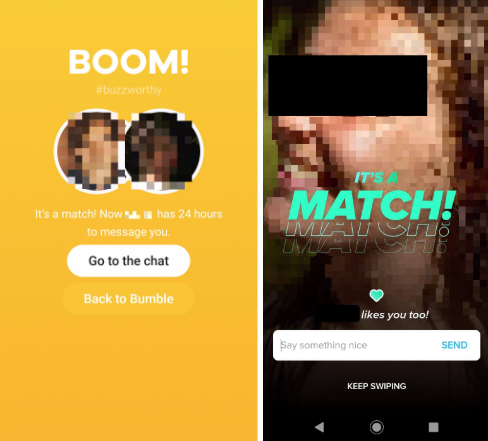

Matching occurs when both users swipe right, indicating a like. When this occurs, both platforms celebrate the accomplishment with colourful animations and bold fonts.

Upgrades

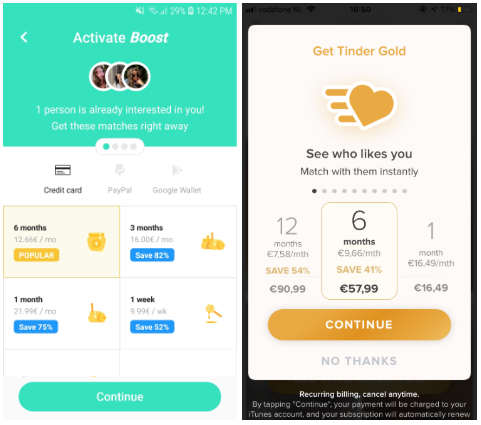

Both platforms allow and encourage users to upgrade their account. On both platforms, features include but are not limited to: Skip the queue/Spotlight (be the top profile in the area), see who already likes you, control who you see. However, Bumble differs slightly on one key feature. As woman must initiate the conversation, men were reminded that they are provided one free ‘Extend’ per day (additional are available for a fee).

Everyday use

After downloading, logging in and setting up the profile we focused on the everyday use of both Tinder and Bumble, which means the activities users regularly engage in such as swiping, matching and chatting. This part included focusing on the functionality, the options and affordances that are part of the app.

Ethical considerations and limitations

There were however some ethical considerations to consider choosing this method. So firstly we would unintendedly disturb other real users of the app with our fake accounts. (Light et. al). This can be particularly sensitive on a dating app with some waiting to fall in love head over heels. We have kept our interaction with other users as limited as possible.

Second, since we did not explicitly ask anyone’s approval, neither for them being a research object nor using screenshots that include their profiles or interactions, we did not officially have their consent. (Light et al.) We have blurred names and pictures in order to guarantee the user’s privacy.

Moreover, as our research group consists of members who idenntify as cis-, western millenials, this is the lens through which these applications were analyzed.

We did get the cis-male straight and cis-female straight and pansexual options in our walkthrough. However, since not every aspect of the application is openly accessible, our interpretation of how the app influences their user’s behaviour is limited to what we could see.

Gender, sexuality, and feminism

In their research, authors MacLeod & McArthur argue that dating apps typically fail to incorporate “nuanced understanding[s] of gender” (836). While this corroborates with our experience with Tinder, Bumble’s recent updates have added more options for gender expression. As we mentioned users of both apps are required to indicate their gender upon registration. With Tinder listing only the gender binary, Bumble gives its users many gender identifications to choose from. While apps such as Bumble were previously criticized for a “cisnormative” and “static and narrow understanding of gender,” the company has since broadened their options (Bivens and Hoque 450).

Sexuality

In addition to conforming to the gender binary MacLeod & McArthur furthermore argue that within traditional dating sites, many design decisions are made based on the assumption of heteronormativity. However, Bumble does attempt to challenge this notion. In the difference we discussed in the walkthrough in allowing users to choose a nonheterosexual relationship for Bumble and Tinder, this shows. When a user identifies as Male on Tinder, it is automatically assumed that the user is seeking a female partner, whereas Bumble allows the user to choose different options.

Additionally, Bumble’s most distinguishable trait – that power lies with women – is a privilege that is only extended to women within heterosexual relationships. Bivens and Hoque argue that this feature not only favours straight female users, but it suggests that men exist in an “intrinsically brusque and brash state of being, only capable of performing a savage performance of masculinity” and further assumes that aggression is something exclusive to heterosexual relationships (Bivens and Hoque 449). Like gender, sexuality is mediated and controlled within these apps’ interfaces – interfaces that largely uphold cycles of heteronormative design decisions.

Love costs

Beyond registration options, gender also plays a role in how users interact with the applications, more specifically, with Bumble, gender is integrated into the business model. Within heterosexual matches, women are given 24 hours to initiate conversation. If they do not, the match disappears and neither party can communicate. However, the app provides several ‘premium upgrade’ options that allow men to stand out. For example, men can ‘Activate Boost’ and extend the deadline for another 24 hours. Of course, this feature comes with a fee. As a result, more than 10% of Bumble’s users pay for monthly subscription fees which is more than double that of Tinder (Bivens and Hoque).

Gamification

Gamification is a concept to describe “a new technology that incorporates elements of game play in nongame situations” (Prince 162). According to Prince, it is a way to engage and incentivise individuals by providing trophies, expressive stimulus, or other rewards. Throughout both apps, these incentives are put in place and users are rewarded for activities such as finding a match. “It’s the gambling-like reward, that dopamine rush of the ‘It’s a match,’ screen” says Scott Hurff, the former lead designer at Tinder. Like gambling, users are encouraged to use real money to ‘unlock boosts,’ buy ‘Tinder Gold,’ or earn coins to increase their odds and position themselves more favourably. By introducing gaming elements, both apps aim to create environments where the possibly tedious activity of searching for a partner is turned into a potentially addictive and costly experience.

Platforms and Big Data

Although dating apps have reshaped contemporary dating, Albury et al. argue that there has been little research into how they collect data and how that information is used. Dating apps are “are intense sites of data generation, algorithmic processing, and cross-platform data-sharing,” they argue (1).

Lifestyle and preferences

Beyond usage data and user information such as date of birth, gender, and name, both apps heavily encourage users to provide more detailed accounts of their behaviors and interests. For example, Bumble pushes users to indicate their education level, their religion, the frequency of their drinking and/or drug use, and their political leanings, just to name a few.

Location data

While relaying location has always been crucial within online dating systems, mobile dating apps are normalizing location data collection and provide a clearer picture of user activity. Due to an “unprecedented ability to capture and store patterns of interaction, movement, transaction, and communication” location data is being tracked on an enormous scale (Albury et al. 4).

Platforms for your convenience

While not a requirement, both apps encourage users to register or ‘enrich’ their profiles by connecting to other platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, or Spotify. For example, upon first entering the apps, connecting via Facebook is the most visually prominent way to access the app. In contrast, Bumble and Tinder’s respective alternative options are less emphasized. Through these distinctions, cross-platform connectivity is both built in and encouraged. Similarly, if a user decides to link to their Instagram or Spotify accounts, their information (photos or favorite songs) are automatically featured prominently on their profile.

Match made in heaven?

While these features are packaged as a way to entice potential partners and ‘develop meaningful connections,’ the apps are actively profiting. For example, app developers use this data to optimize user experience, improve the app, and ultimately “enhance the opportunity to monetize that experience” (Albury et al. 3). Despite users not being able to swipe right more than a hundred times a day, they can of course get Tinder Plus to unlock this feature for a monthly fee.

Beyond optimizing the experience, these apps heavily profit from the amalgamation of user data. For example, hidden within Bumble’s Terms & Conditions, the app states that users “automatically grant [Bumble] a non-exclusive, royalty free, perpetual, worldwide license to use [the user’s] Content in any way.” Through this clause, the company can freely use any information provided – whether on the users’ profile or even in private messages. Tinder has a similar condition in place where anything uploaded to the app can be used by the company or sold to third parties.

These conditions also extend to cross-platform integration. In the case of Tinder, once syncing a Facebook account, the user automatically authorizes the company to access and use information “including but not limited to [the user’s] public Facebook profile and information about Facebook friends.” Similarly, when syncing Facebook, Bumble is authorized to “use certain information from [the user’s] Facebook account (e.g. profile pictures, relationship status, location and information about Facebook friends).” This also extends to Instagram.

While information such as geographical data, religious affiliation, or political leanings would have once been unfathomable, users on dating apps are willingly and freely giving this information away.

Conclusion

Since technology is an extension of our cultural values, applications are too. Both Bumble and Tinder have become an important digital ‘wingmate’ for many people. Both Bumble have been criticized for its attitudes towards gender and sexuality. Trough the Walkthrough Method we noticed Tinder’s affordances mainly encouraging users’ cis- and heteronormativity and Bumble’s attempt to counter these firstly in its more elaborate gender- and sexuality options. We also confirmed Bumble attempts encourage allowing women to take the initiative in conversations in cisheterosexual contact.

However, we further noticed the monetization of undoing these features and the commodification of our data. Through the access to rich metadata, corporations can segment users and make assumptions about their consuming habits. In an ever increasing environment where love is digitized, we have also emphasized how users are often asked to consent without fully comprehending the ramifications of their actions.

We hope more research will be done on the way applications reinforce or shape our gender and sexuality and more awareness will be raised on the ways users’ data is captured and commodified in our online looking for ‘the One’.

References:

Albury, Kath, et al. “Data Cultures of Mobile Dating and Hook-up Apps: Emerging Issues for Critical Social Science Research.” Big Data, pp. 11.

Bivens, R., and Hoque, A.S. “Programming Sex, Gender, and Sexuality: Infrastructural Failures in the ‘Feminist’ Dating App Bumble.” Canadian Journal of Communication, vol. 43, no. 3, Canadian Institute for Studies in Publishing Press, 2018, pp. 441–59, doi:10.22230/cjc.2018v43n3a3375.

Chamourian, Elizabeth. Identity Performance and Self Presentation through Dating App Profiles: How Individuals Curate Profiles and Participate on Bumble. Diss. (Master Thesis). The American University of Paris, 2017. ProQuest LLC: Ann Arbor, 2019.

Davis, Jenny L., and James B. Chouinard. “Theorizing Affordances: From Request to Refuse.” Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society, vol. 36, no. 4, Dec. 2016, pp. 241–48. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1177/0270467617714944.

Gillmor, C.S. “Stanford, the IBM 650, and the First Trials of Computer Date Matching.” IEEE Annals of the History of Computing 29.1 (2007): pp. 74–80. Web.

Lefebvre, Leah E. “Swiping Me Off My Feet: Explicating Relationship Initiation on Tinder.” Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, vol. 35, no. 9, SAGE Publications, Oct. 2018, pp. 1205–29, doi:10.1177/0265407517706419.

Light, Ben, et al. “The Walkthrough Method: An Approach to the Study of Apps.” New Media & Society, vol. 20, no. 3, Mar. 2018, pp. 881–900. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1177/1461444816675438.

Macleod, Caitlin, and Mcarthur, Victoria. “The Construction of Gender in Dating Apps: An Interface Analysis of Tinder and Bumble.” Feminist Media Studies, vol. 19, no. 6, Routledge, Aug. 2019, pp. 822–40, doi:10.1080/14680777.2018.1494618.

Prince, J. Dale. “Gamification.” Journal of Electronic Resources in Medical Libraries, vol. 10, no. 3, July 2013, pp. 162–69. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1080/15424065.2013.820539.

Sumter, Sindy R, et al. “Love Me Tinder: Untangling Emerging Adults’ Motivations for Using the Dating Application Tinder.” Telematics and Informatics, vol. 34, no. 1, Elsevier Ltd, Feb. 2017, pp. 67–78, doi:10.1016/j.tele.2016.04.009

Timmermans, Elisabeth, and De Caluwé, Elien. “To Tinder or Not to Tinder, That’s the Question: An Individual Differences Perspective to Tinder Use and Motives.” Personality and Individual Differences, vol. 110, Elsevier Ltd, May 2017, pp. 74–79, doi:10.1016/j.paid.2017.01.026.

“Who we are.” Eharmony.com Accessed 24th of October 2019. https://www.eharmony.com/about/eharmony/

Whitty, Monica T. “Online Dating.” International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences. Second Edition. Elsevier Inc., 2015. 212-216. Web.

Yashari, Leora. “Meet the Tinder Co-Founder Trying to Change Online Dating Forever.” Awaken. 2015. https://www.awaken.com/2015/08/meet-the-tinder-co-founder-trying-to-change-online-dating-forever/