What Does a Feminist Approach to Deepfake Pornography Look Like?

Ida Raffaghello (11903341), Laura Kastalio (12768537), Sanne Kalf (11290196) and Erinne Paisley (12516325)

Word count: 2749

Introduction

This project focuses on the research question: What does a feminist approach to deepfake pornography look like? Deepfake’s have their historical roots in “computer-generated imagery” (CGI) (Maras and Alexandrou 256). The technology itself uses a combination of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning to replace the face of a subject with another (256). Deepfake technology scans the Internet for available images of an inputted subject’s face, through social media platforms and search engine image results, and is able to automatically evolve when new images emerge. This allows the technology to create increasingly realistic videos and images.

New applications, such as the application “Deepfake” and “Deepnude”, allow for deepfake creation to be easily accessible to the average person. This increased availability and usability has also lead to more deepfake content. According to the Amsterdam-based organization “Deeptrace”, as of October 2019 there were over 14,678 deepfake videos online (CNN 2019). This was an 84% increase since the previous December. Of this content, 96% was pornographic content and 100% of these videos replaced the female subject – typically celebrities or targets of revenge porn (CNN 2019; Harris 100; 128).

Context and debate

The surrounding academic conversation about deepfake pornography, from a feminist perspective, highlights many of the issues with the technology. From a historical perspective, the issue of media extending the male gaze reaches as far back as the invention of the camera where a subject was “targeted” and “captured” by the photographer (Thompson and Wood 565). As Thompson and Wood state: “[to gaze] implies a social, psychological relationship of power in which the gazer is superior to the object of the gaze” (Kenneth Nyguyen 2007, np) (562). From this perspective, deepfake pornography is an example of the non-consensual capture of a woman and the reduction of this actor into a passive, and silent, state where the subject cannot defend themselves (565).

As well, the issue of non-consensual deepfake pornography relates to broader feminist academic work on consent as a function of power (Pena and Varon 2019). When consent is viewed in this way, non-consensual deepfake pornography can be seen as an extension of patriarchal power and a form of sexual violence. Additionally, by looking at Liz Kelly’s (1988) concept of the “continuum of sexual violence” we can see how this form of sexual violence is harmful (McGlynn et al. 27). According to this theory, it is counter to a feminist framework to assign hierarchical ranking to different forms of sexual violence because all forms feed into one another creating an overall environment that allows, and even encourages, this type of behaviour (28).

Framing our solution

Most commonly, the issue of deepfake pornography is discussed from a regulatory perspective. Large technological organizations such as Google and Facebook have recently launched heavily funded projects to increase their deepfake detection technologies (Dufour et al. 2019; Schroepfer 2019). As well, platforms such as Gfycat and Pornhub, that are popular for the distribution of pornographic deepfake content, have begun using AI technologies themselves to detect content for removal (Matsakis 2018). The newest iteration of creative deepfake detection and regulation involves the use of blockchain technology. This technology provides information in a decentralized and public way, providing a potentially ideal technology for verifying content, as seen with the company Factom’s blockchain-based deepfake detection technology (Martinez).

Despite the mainstream conversations about deepfake, and deepfake pornography, focusing on regulatory solutions our following creative response to the issue approaches the topic from a different perspective; we have created an application that aims to empower users to express and explore their sexuality in a consent-based environment. Th decided to approach the topic from this framework is based on two main reasons. Firstly, as Gunnarsson explains: “…discourses used to name sexual violence may in fact perpetuate the very problem they set out to describe, by freezing women into powerless positions of rapability.” (4). In this way, we did not want to frame the issue as one of “victimization” where the subject has no power. Instead, we aim to re-frame the issue at hand as one of scarcity when it comes to platforms that allows users to consensually express, explore, and even financially profit from their sexuality through deepfake technology. Secondly, as Hassinoff explains: “…casting perpetrators as villains and monsters implicitly validates the dominate sex-gender system as basically sound and falsely locates harm and violence outside of everyday life and intimate relations.” (9). In this way, by framing perpetrators as outside of the norm, dialogues about sexual violence do not acknowledge the mainstream nature of this violence. Instead, we want to acknowledge that the ability to feel safely empowered when it comes to sexuality is instead outside of our society’s mainstream. Regulation is still an important aspect of the future of deepfake pornography however, due to these two factors, through our creative response we aims to contribute to a dialogue that focuses instead on empowerment.

The relevance of deepfake technology

One of the primary issues associated with deepfake technology and the ‘post truth era’ new media landscape in general is the difficulty of deciphering truth from fiction in the digital sphere. Deepfake technology contributes to the misconstruction of truth and the resulting impossibility of distinguishing between “patrician insights and plebeian gossip”, in a digital environment where information ranking is done on the basis of popularity rather than truth (Lovink 1). While the AI technology behind deepfakes has potential positive uses, as for example in the fields of art, education and design, it is in the misuse of this technology and the concurrent spread of digitally altered material through social media platforms that the greatest issues arise. As suggested by Lovink, this issue calls for critical reflection and digital literacy, in order to distance ourselves from the idea that everything we see online can be seen at face value (Lovink 3). However, in regards to deepfake content, digital literacy alone will not suffice in deciphering what is digitally altered.

Deepfake technology is furthermore a natural fit for the inflation of information cascades; the human tendency to credit what others know, made worse by human predisposition to propagate negative or shocking information, such as deepfake videos which are by nature, constructed to shock and stand out (Chesney and Citron 12). Pornographic content specifically falls directly into this ‘shock value’ category, even more so when it is altered to make it appear as though it features someone you may know. While the spreading of deepfake content through various digital platforms presents an issue in and of itself, the most relevant problem remains to be that of technological misuse. The misuse has been facilitated by the easy and widespread access to said technology through the availability of easy to use apps. “The tendency for technologies to spread only lags if they require scarce inputs that function (or are made to function) as chokepoints to curtail access.” (Chesney and Citron 8). The idea of necessary scareness presents the idea that technologies can only be contained when there is scarcity in inputs, availability or knowledge. Once a technology spreads to the general public and is easy to access, as has occurred with deep fake technology, is when greater problems arise.

Data and privacy issues

While the spreading and misuse of technology presents one side of the problem, deepfake technology also raises wider questions about data and privacy protection online. Deepfake videos are most often the result of an unauthorized exploitation and reengineering of other people’s pictures and data. Most of which, can be obtained through a simple Google search or access to social media accounts, raising the question of to what extent we can maintain an expectation of privacy online? Chesney and Citron argue, “Deep-fake videos do not involve invasions of spaces in which individuals have a reasonable expectation of privacy.” (Chesney and Citron 36). While the extent of this statement is debatable when discussing the misuse of pictures and data beyond their original purpose, it highlights another reason why it is crucial to focus on the idea of introducing the notion of consent to deepfake technologies, as is the approach of this project. When questioning whether technology has made is too easy to obtain private data the blame of privacy violation often falls to the private companies and platform providers. “Although private companies have enormous power to moderate content (shadow banning it, lowering its prominence, and so on), they may decline to filter or block content that does not amount to obvious illegality.” (Chesney and Citron 10). With both companies as well as the law focusing on technicalities and definitions of terms, it is of even greater importance to take back ownership of one’s personal data and focus on the consensual use of data online.

Technical walkthrough

This section will cover the technical walkthrough of the application, RealDeep, and it’s affordances. The application allows to look at deepfake pornography from a feminist perspective, as it is principally consent-based, and therefore takes consent in consideration with regards to its interface. The apps function is threefold as the application functions as database for deepfake content as well as a social environment and a monetary gain for users that want to sell their content for deepfake editing purposes. The application works on a membership basis for a small fee each month. Ideally, the application is downloaded to a smart device such as a smartphone or tablet. This walkthrough will guide a potential user through the application as if it were a smartphone app.

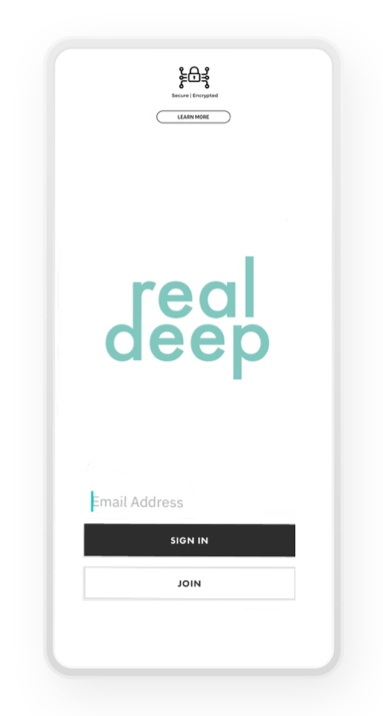

In figure 1, the enrollment screen is shown. This is the first introduction of the user with the application; therefore, it is brought to the user’s attention that the application is encrypted (in the top part of the screen), suggesting means of safe data storing, which is critical as the application contains sensitive content. Underneath the encryption button, there is a button saying ‘learn more’, which the user can click on and read more about RealDeep and its premises for safe sharing.

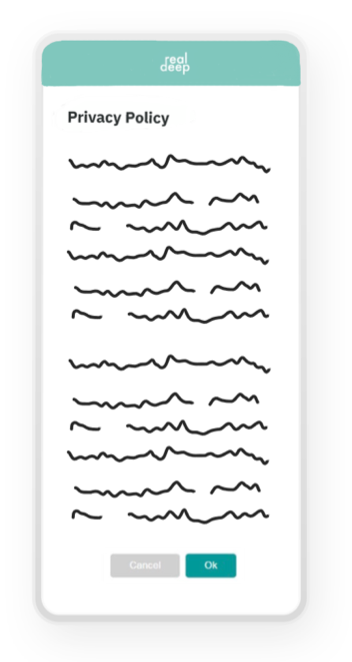

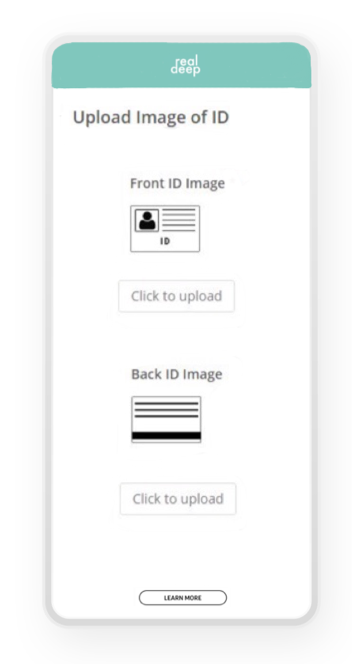

By clicking ‘sign in’, existing users can sign in, and by clicking ‘join’, new users can enroll to the application. While doing this, new users are first redirected to the privacy statement and terms of service, which they are obliged to accept before they enroll (fig. 2). When users accept the privacy statement, they are redirected to uploading an image of their ID, to confirm that the settings that they will complement further in the enrollment process are based on their own, thus preventing users from using false identities (fig. 3).

The terms on uploading an ID, data storage and protection are enclosed in the privacy policy prior to the upload. In the bottom part of the screen, the ‘learn more’ button is placed as well, so users can always obtain more information on what they are consenting to.

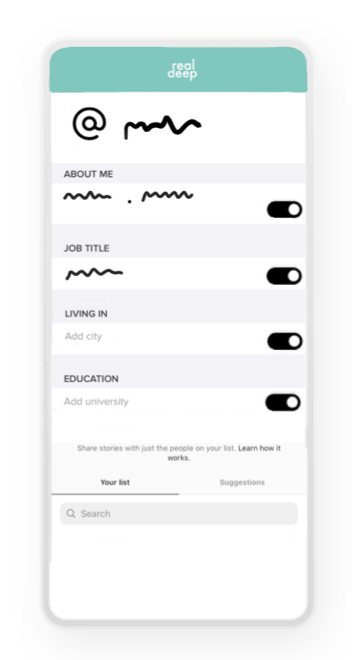

After uploading an ID, users are asked to fill in personal information (fig. 4), as well as their payment information for their monthly subscription. Data is only stored on the user’s phone and in the cloud-based RealDeep database, but is not used for further commercial uses.

Their personal information can be adjusted as the user desires, and every piece of data contains a switch toggle that users can use to decide what they want to show on their profile and what not – as profiles are by default private.

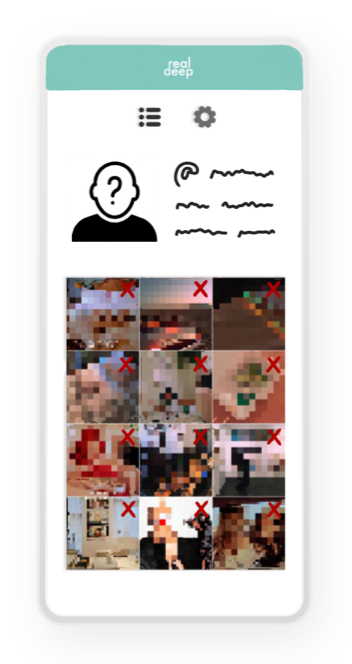

In the lower section of the personal settings, privacy settings are able to be extended by the user’s ability to add specific people that can view their profiles only. There is also the option of adding or removing specific photos of the user’s profile, by removing them with the red crosses (fig. 5).

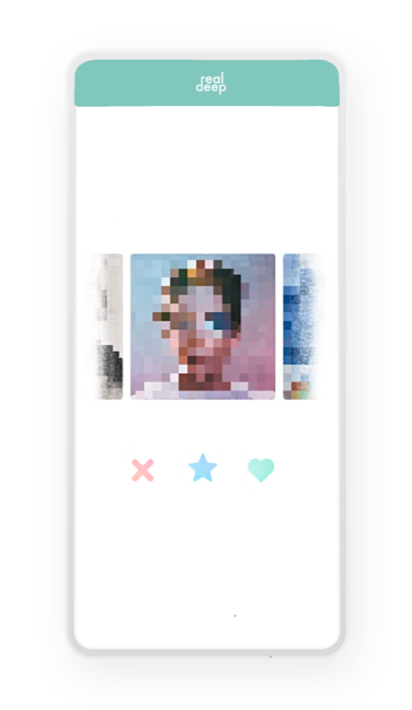

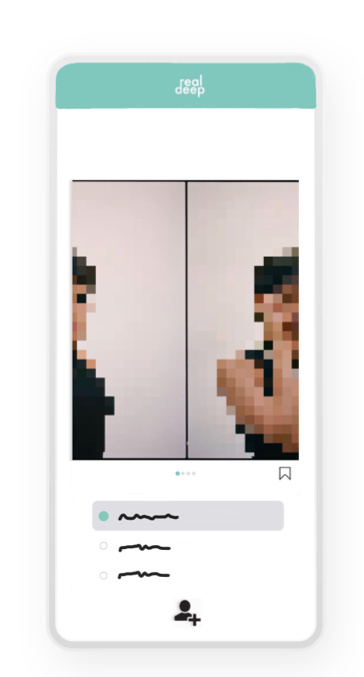

The user feed can be found on clicking the left upper button in figure 5, next to the settings-button. The feed is based on a swiping principle (fig. 6) and is randomized, hence there is no option for searching. Categorization of users based on algorithmic logic hereby is disabled. Users can only be found by other users by adding them to their ‘list’, which is assigned under preferences (fig. 4). By means of this, users are only able to find people they know and that have consented sharing their username with the other. Users can’t randomly intrude others or search for people. If users do find each other in the randomized feed and want to get in contact with each other, the star-button in the middle can be pressed in order to ask for consent. The user that is asked for consent will accordingly receive a request which he/she can either accept or deny (fig 7).

The request-screen in figure 7 also shows options for buying a user’s content in order to use them for creating deepfake material, from which users can make money. Uploading is free, but there are fees for downloading.

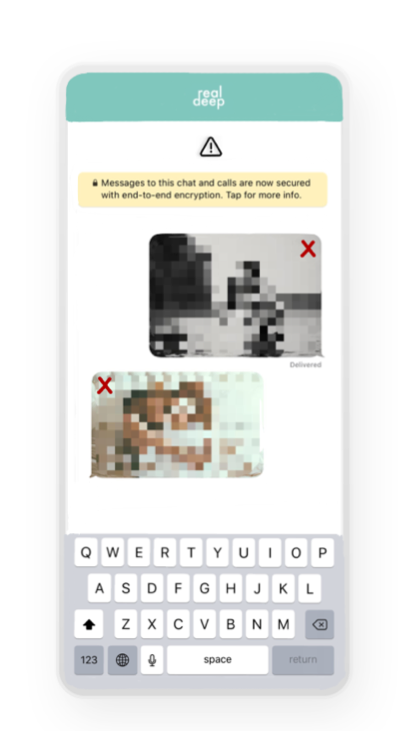

Users are able to send photos and chat with other users (which they must ask for consent in order to get in contact with, through ‘requesting’ a profile) through a chat function (fig. 8). Users are able to delete photos or messages at all times. In order to avoid deleted content to be (mis)used, screenshotting is disabled as well.

Last but not least, after each session users are automatically logged off from the application, in order to avoid content getting into wrong hands (when, for example, a device has been stolen).

Outcomes

The nature of this app is a consent-based environment, where the only material that is used are pictures/videos that someone has allowed other people to use. The aim is to increase the feeling of self-determination, autonomy, and freedom in the pornographic industry and among people using the deepfake apps, as they have the power to decide what to post. The app gives the user a ‘sense of agency’, as individuals have the ability to choose whether to share a picture or not, as well as the possibility to decline offers. A clearly visible delete button is always displayed, to make it easier to control what content users choose to display in their feeds. Besides the consent-based environment, another outcome of using this app are the monetary gains that can be made by users. By getting paid per download or view per photo, users are able to profit. An important fact to take into consideration, is whether it is exploitation to make money in this way. However, according to Hallstein et al. (2001), it is empowering to make decisions, regardless of what these decisions entail. Therefore, according to the third-wave, making money via the app can be seen as an empowering method allowing people can make their own decisions.

Critiques

The approach offered does not come without critique. The most common critique is: whether there are any demands of the public for such an application when there are already apps where deepfakes can be created. It is important to remember that the reason that this app would be created, is to create a consent-based environment, rather than meeting the demand by the public. Another important critique which is important to take into account, is how we can be sure that someone is not using someone else’s face. The solution to this, would be to install an ID function used by the app. This would also make it easier to trace a person if he/she if they are distributing images of other people (revenge porn). However, the screenshot function is always disabled, as the purpose of the app is personal enjoyment, rather than leaking pictures of others.

Conclusion

To sum up, 96% of all deepfake images worldwide contain pornographic content. Apps such as Deepnude, give power to the “gazer” and not to the “object of the gaze”. Technology or platforms can be accused of transmitting such fake content, but what is more important is to turn the discourse on such applications to a consent-based environment for people wanting to explore content online. A feminist approach to deepfake pornography content could look like the app RealDeep (safe space sexuality app), turning the discourse into a consent-based app (making use of technology). By letting the person featuring in the image/video give permission to download the content, this consent can be seen as a function of power. Therefore, the third-wave feminist movement, would view this application as a method for empowering individuals, as it allows people to make their own decisions and retaining power over their own bodies.

Bibliography

CNN. “Deepfake Videos Online Jumped 84% in Less than a Year, and They’re Nearly All Porn”. CNN. Accessed 9 October 2019. <https://edition.cnn.com/2019/10/07/tech/deepfake-videos-increase/index.html>

Chesney, Robert and Keats Citron, Danielle.“Deep Fakes: A Looming Challenge for Privacy, Democracy, and National Security.” SSRN Electronic Journal. 2018, doi:10.2139/ssrn.3213954.

Dufour, Nick et al. “Contributing Data to Deepfake Detection Research.” Google AI Blog. 2019. Accessed 14 October 2019. <http://ai.googleblog.com/2019/09/contributing-data-to-deepfake-detection.html>

Gunnarsson, Lena. “‘Excuse Me, But Are You Raping Me Now?’ Discourse and Experience in (the Grey Areas of) Sexual Violence”. NORA – Nordic Journal of Feminist and Gender Research. 26:1. (2018): 4-18.

Hallstein, Lynn. Shugart, Helene. & Catherine Waggoner. “Mediating Third-Wave Feminism: Appropriation as Postmodern Media Practice.” Critical Studies in Media Communication, 18:2. (2001): 194-210.

Harris, Douglas. “Deepfakes: False Pornography Is Here and the Law Cannot Protect You.” Duke Law & Technology Review, vol. 17, 2019, pp. 99-127.

Hasinoff, Amy Adele. Sexting Panic: Rethinking Criminalization, Privacy, and Consent. University of Illinois Press, 2015.

Peña, Paz, and Joana Varon. Consent to Our Data Bodies Lessons from Feminist Theories to Enforce Data Protection. 8 March 2019. pg. 1-30. <Https://codingrights.org/docs/consenttoourdatabodies.pdf>

Lovink, Geert. “The Society of the Query and the Googlization of Our Lives”. Eurozine. 2008. Accessed 20 October 2019. <https://www.eurozine.com/the-society-of-the-query-and-the-googlization-of-our-lives/>

Maras, Marie-Helen, and Alex Alexandrou. “Determining Authenticity of Video Evidence in the Age of Artificial Intelligence and in the Wake of Deepfake Videos”. The International Journal of Evidence & Proof. 23:3. (2019): 255-62.

Martinez, Antonio Garcia. “The Blockchain Solution to Our Deepfake Problems”. WIRED. 2018. Accessed 14 October 2019. <https://www.wired.com/story/the-blockchain-solution-to-our-deepfake-problems/>

Matsakis, Louise. “Gfycat Uses Artificial Intelligence to Fight Deepfakes Porn”. WIRED. 2018. Accessed 14 October 2019. <https://www.wired.com/story/gfycat-artificial-intelligence-deepfakes/>

McGlynn, Clare, et al. “Beyond ‘Revenge Porn’: The Continuum of Image-Based Sexual Abuse.” Feminist Legal Studies. 25:1. (2017): 25-46.

Peña, Paz, and Varon, Joana. Consent to Our Data Bodies Lessons from Feminist Theories to Enforce Data Protection. Coding Rights, Privacy International and International Development Research Center, 2019. <https://codingrights.org/docs/ConsentToOurDataBodies.pdf>

Schroepfer, Mike. “Creating a Data Set and a Challenge for Deepfakes”. Facebook AI. 2019. Accessed 14 October 2019. <https://ai.facebook.com/blog/deepfake-detection-challenge/>

Thompson, Chrissy, and Mark A. Wood. “A Media Archaeology of the Creepshot.” Feminist Media Studies. 18:4. (2018) 560-74.