You Cannot Weigh Beauty (but Your Body can be Commercialized)

Introduction

In the media women bodies are often portrayed by the preference of thin body types characterized as ideal body types (Martin et al 609). For instance, when looking at the United States, women shown on television tend to weigh 15 percent less than the average American woman (Barriga et al 129). Moreover, women with larger body types are often presented negatively through the medium and remain underrepresented. Furthermore, studies show that women with larger body types are considered less likely to receive a role on television in a professional setting (128).

Next to television, thin, white and preferably partially clothed women also rule the roost in mainstream advertisement (Barriga et al 129, Doshi 187). Due to the overload of thin bodies presented as ideal bodies in the media, individuals tend to compare their bodies to unrealistic images causing them to get dissatisfied with their own bodies, especially (young) women (Martin et al 609). The body dissatisfaction these women experience results into them wanting to lose weight and this is where today’s health and fitness applications play their part (Martin et al 609, Depper & Howe 104).

When looking at women fitness apps, unrealistic bodies as ideal bodies overrule normal body types the same way they do in other media by showing curvy, yet slim bodies (Doshi 187). These women fitness apps claim to help women to their, presumed, ideal body goals, correlating to the body images shown by these applications (184). However, many of the body types portrayed by these fitness applications are not achievable for a lot of its users. Therefore this research aims to develop a new and more realistic fitness app for women by analyzing a number of existing fitness applications by using Ben Light, Jean Burgess and Stefanie Duguay’s walkthrough method, such as ‘The be.come project’ and ‘Zombie Run’. During this research the application SWEAT, which claims to be ‘the world’s best female fitness community’, will be used as the main case study.

Furthermore, this research uses academic literature by Marissa J. Doshi who writes about mobile phone applications which are advertised to women in correlation to health management and a text by Deborah Lupton who writes about platforms and their promise to users to achieve their health goals to analyze problems embedded in today’s existing women fitness apps. Additionally, this research looks at how women’s bodies are used to get applications downloaded or its products sold. Ultimately this research will present a prototype of a more realistic women fitness app by using elements of the evaluated applications and knowledge from present-day research on the topic.

Context and Relevance

This topic is of relevance in consideration of the current debates concerning the human influence on search engines, apps, platforms and algorithms. As Safiya Umoja Noble points out, human designed systems are not neutral, but they replicate the power structures of their context of origin, usually the western, white-male society (3).

Commercial interests are pursued exerting leverage on diffused stereotypes: the present article aims to display and discuss the shared system of categorization that drive the design of fitness apps for women. In fact, the interfaces result in reflecting commonsensical assumptions around the female body, influencing the app and its fruition experience. Users are presented specific body types, conceived as the final goal and desired result for everyone, and fitness workouts designed in order to achieve that specific aesthetic result,disregarding the actual demand of the users.

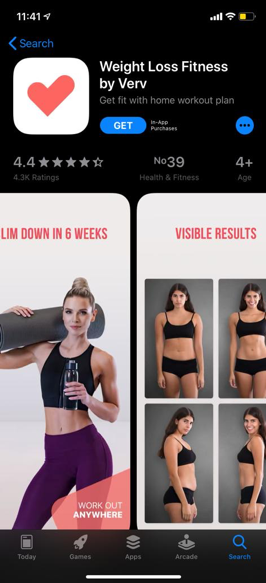

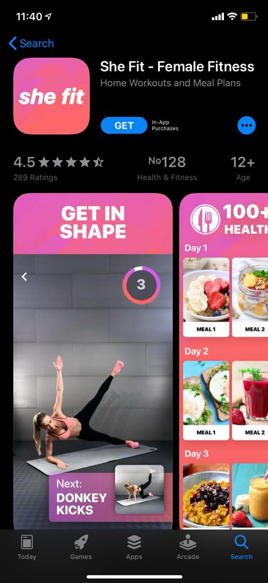

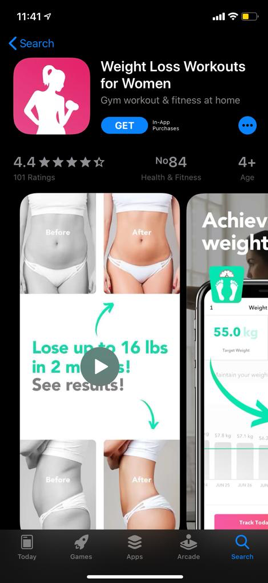

The following examples are screenshots captured from the Apple AppStore, and they are the first results given for the search “Fitness”. Not only our attention is caught by the prominent use of pink and white (commonly considered “feminine” nuances), but we can immediately notice that the goal of the apps is to let the user “slim down”, “get in shape”, and in general lose weight and get to “visible results” (Wolchover).The final outcome of using these apps is clearly visualized in their presentation: become slim, slightly muscular women, just as the girls we can see in the apps.

While there is obviously nothing wrong with having or desiring this body figure, we discuss that the repeated suggestion of these images is the reflection of a wider and rooted conception of the female body that neglects the actual, immense diversity of the human physical, and does not consider the real wish of a varied audience. With the hope of seeing a more diversified environment in the app store, we here discuss the topic in response to the need of a growing consciousness around the bias and influence exercised through the digital world.

As Wachter-Boettcher argues, the digital world is not inherently negative nor positive, but facing the growing embeddedness of technology in our everyday life it becomes more and more important to be aware of how it can be biased, harmful or even alienating (8). For instance, at an individual scale, the psychological effects of constantly being proposed a body that does not belong to you and a way to be fit that does not suit your abilities or your necessities are not be underestimated. On a larger scale, we can embrace the perspective of Donna Haraway, who conceives a productive alliance between women, machines and new technologies, in order to overcome the dualisms that normalize subjectivity (Guerra, 248).

The following sections will take the SWEAT app into consideration, a famous fitness app, discussing the commercialization of ‘body positivity’ (the acceptance of the self regardless of imposed body images) through social media platforms and apps, and how this conception can still be substantially biased and stereotypical.

Methodology: where is the middle ground?

To be able to break free from the existing fitness applications where the bodies of women are shown as desirable and are not inclusive of different body types, the design of the application will be based on a body neutral perspective. As pointed out earlier, the existing applications that fall under “women’sfitness” in the app store all market a solution for skinny “bikini-ready” bodies and use mostly white females as promotion. Body neutrality is a movement that has risen as a response to the commercialization of the term “body-positive”. The movement preaches to focus on the function of the body instead of the presentation of it. For example, being healthy enough to run a certain amount of time, or to carry something heavy, or to get yourself from point A to point B (Weingus).

To be able to create a prototype of the application for our intervention we viewed four existing applications that are considered to be body neutral using the walkthrough method. We looked at each applications vision, operational model and governance (Light, Burgess and Duguay, 889).

Be.come project

Vision:

– The be.come project is marketed to be inclusive for all-women. It also promotes body neutrality as “We prefer the use of body-neutrality because that means some days we feel good about our bodies, some days we feel bad about our bodies, but all days we respect our bodies.”

– Uses 25-minute workouts consisting of a combination of rhythmic Pilates and yoga

Operating Model:

– Subscription (35USD a month)

Governance:

– To unlock the next workout and close the workout, a small set of questions about your emotion/feeling is asked, focus is therefore shifted away from body image and towards functionality.

– The workout video includes women who volunteer to appear in the video. Therefore, a genuine feeling is communicated.

Evolve 21

Vision:

– Have inclusive workouts for people of all abilities and disabilities.

– Raise money for cerebral palsy foundation

Operating model:

– Funded through foundation

Governance:

– Highly customizable to accommodate everyone who uses it. Can turn off certain exercises.

– Focus on mental well-being is very evident, lots of yoga and meditation

Zombies Run

Vision:

– Combining running workouts with a mobile game to motivate people.

– Audio-adventure

Operating model:

- Free download. Inside the application a membership is available for €6.49 a month and unlocks extra material.

Governance:

– A fun and distracting way to work out. Rather than traditionally following instructions for a workout, the auditory game-element becomes your guide.

7 – seven-minute workouts

Vision:

– Once a day seven-minute-high intensity workouts

– Science-backed method for all people

Operational model:

– Monthly subscription of 9.99 USD

Governance:

– Through short daily workouts, people will have more commitment and create a habit

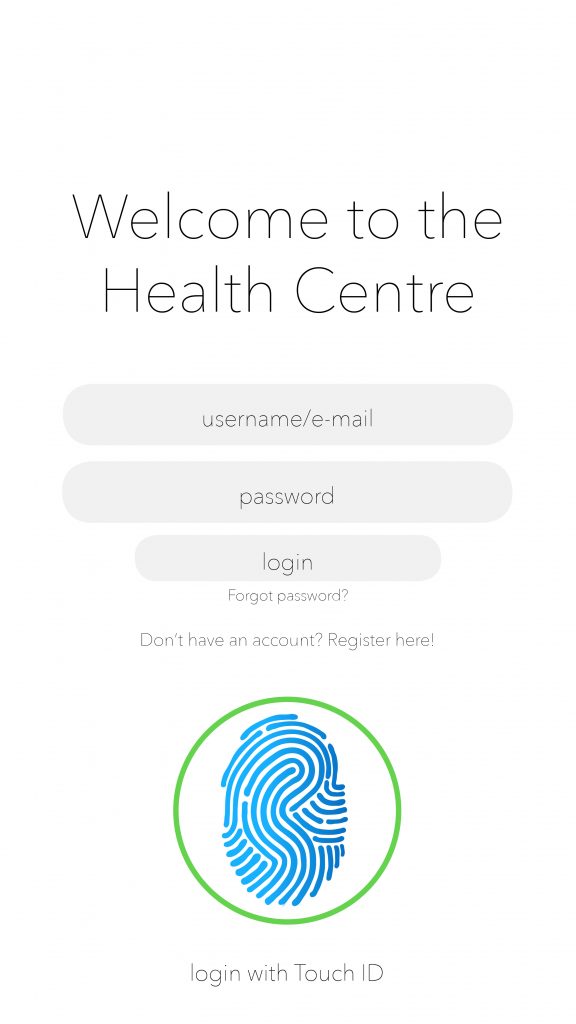

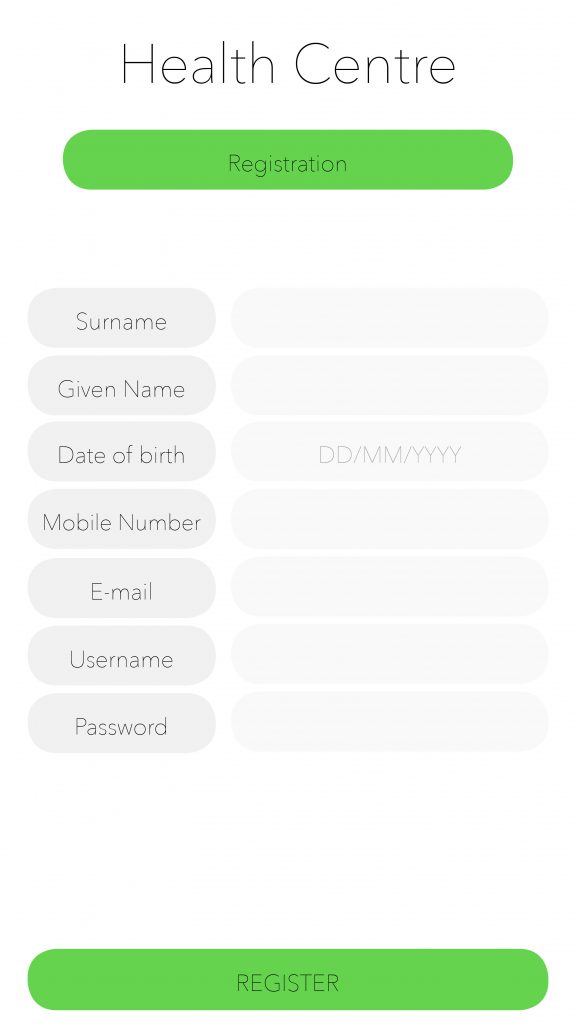

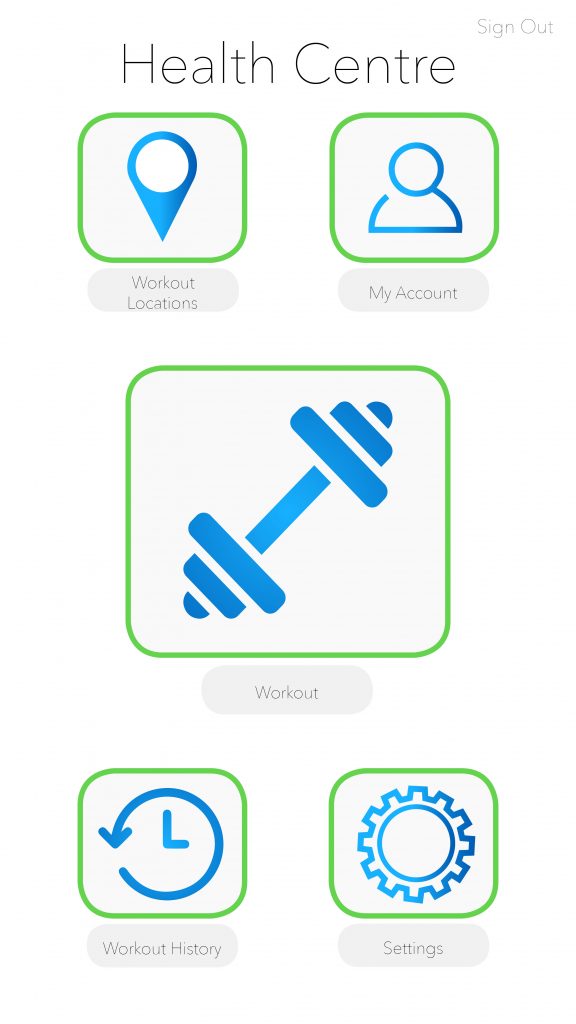

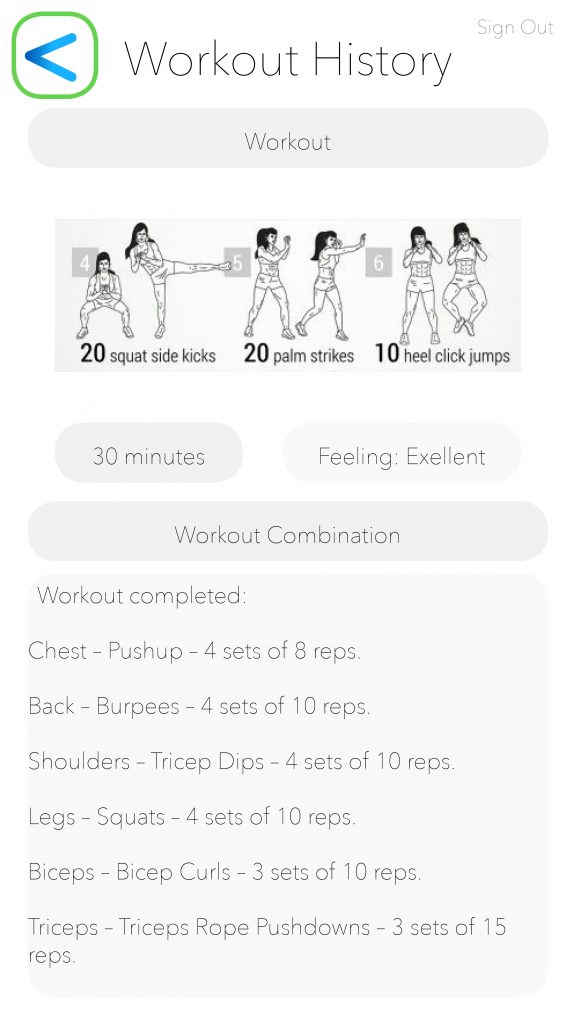

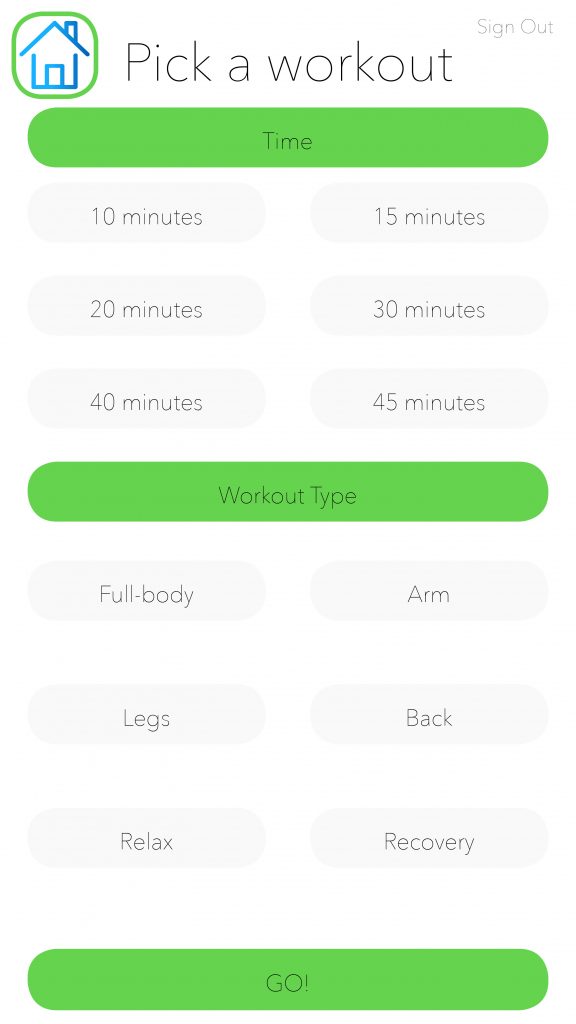

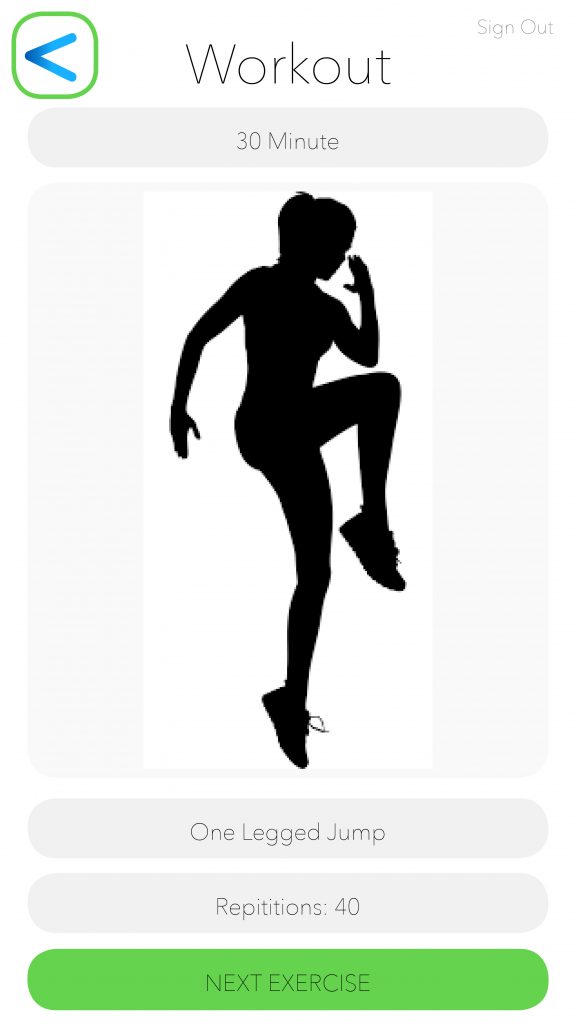

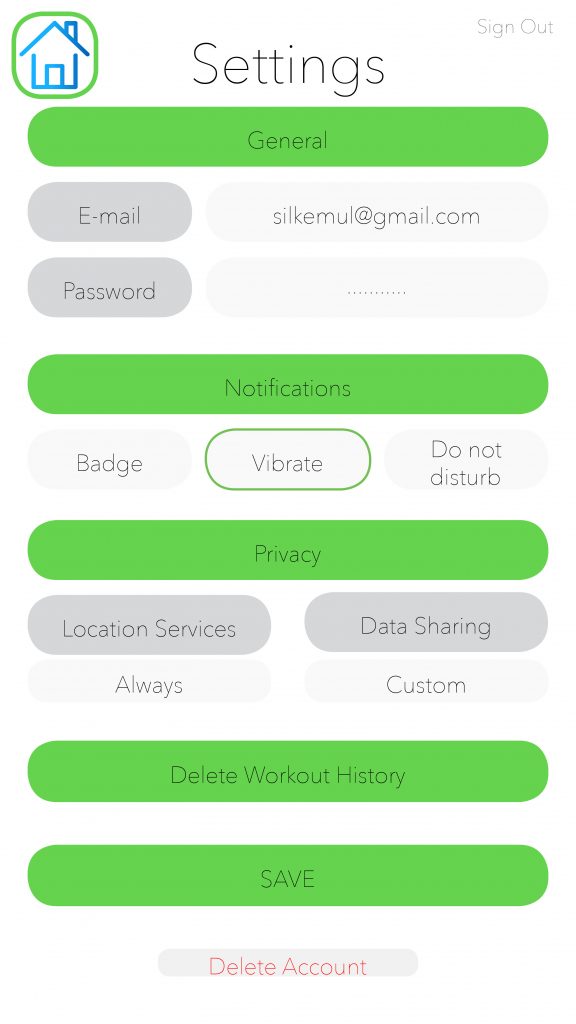

Using the most prominent overlapping characteristics of these applications, we have devised our body-neutral application named “Health Center”. Our walkthrough thus consists of the following:

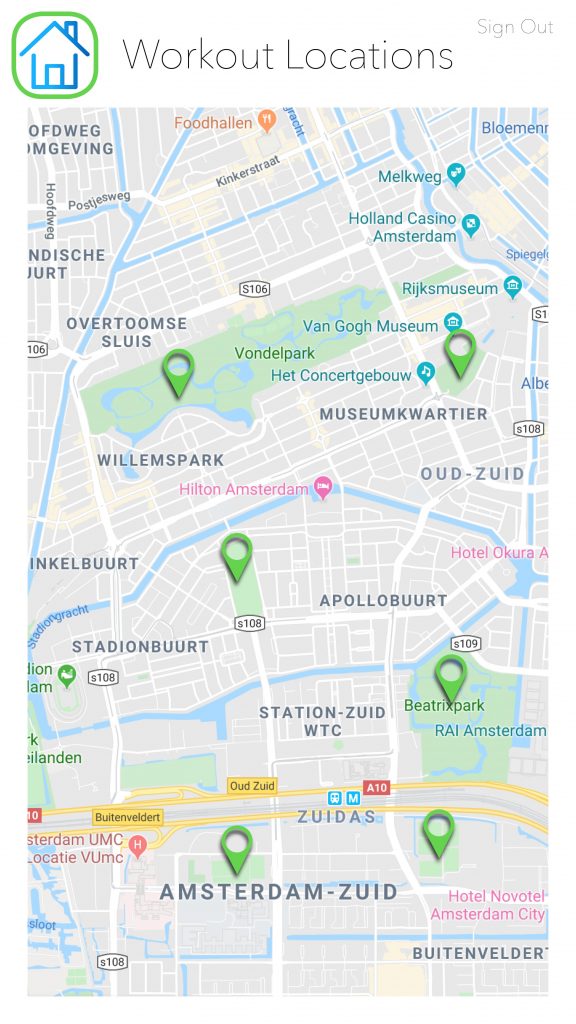

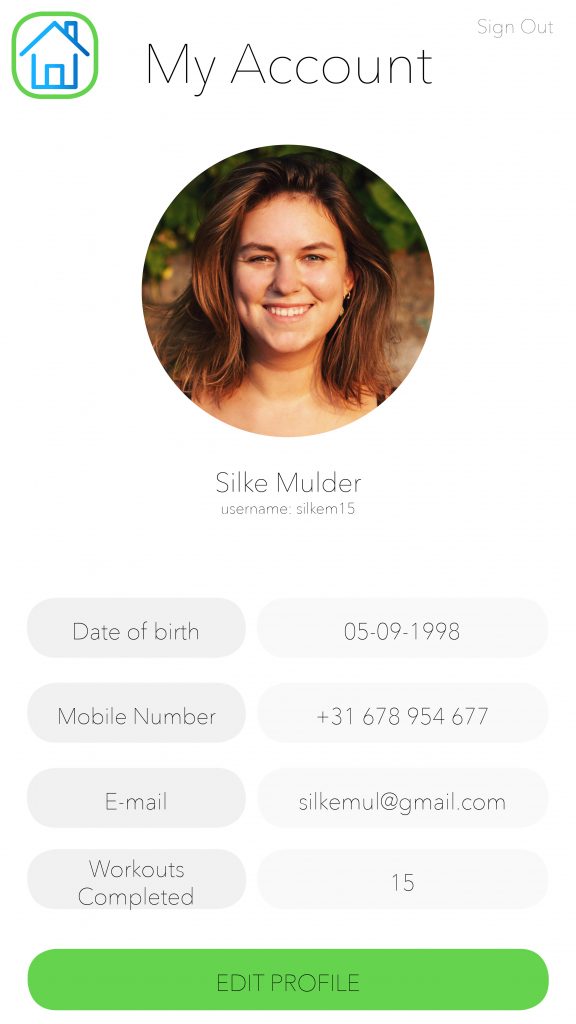

Vision: Health Center will use neutral images, tones and colors to be accessible to all women. Through the use of avatars, we will not depict any live-image of a “correct” body-type.

Operational model: The application will be free and funded through investments.

Governance: The application will include workouts that are repetition based so that all users will be able to work at their own speed, with a timer to make sure they do not lose track of time. The application is accessible to everyone and through the use of an account, personalized to tailor your specific needs. All the workouts will be without any gym tools to eliminate the need of a gym. The map function even highlights the public places where you can work out.

Analysis

The fitness apps designed explicitly for female consumers impose an idea that women should take responsibility for their physical condition in a way that actively draws from socially constructed femininity ideals. The aim of this analysis is to outline how the women fitness apps are portrayed in the app store through a conceptualization of health supported by the standardized gender norms.

Women fitness apps

The majority of the apps commonly depict healthy bodies as being slim. However, such body is also presented on the apps’icons as stretchmarks free, with a slim waist and a curvy butt. In this context, the apps follow the mass media that idealize “Barbie”(or nowadays -“Kardashian”) body as both desirable and healthy (Doshi 185).

Henceforth, fitness apps repeatedly emphasize reduction of body fat as the major goal of being healthy. Most of these apps say to help the users get “a tight and toned butt”, “melt the fat away to reveal those beautiful toned muscles”or “sweat, get pumped, lose weight –better you!”(Workout for Women|Weight Loss Fitness App by 7M). The analysis does not suggest that the promotion of an active lifestyle itself is harmful, however, when thinness is presented as central to health, people that do not conform to this ideal are perceived as “imperfect”and needing intervention.

The apps also highly values the healthy body as “bikini ready”, explicitly being directed at women with icons presenting a woman’s torso wearing a bikini bottom. The high positions of these apps in the app store frame bikini-ready body as a year-round ideal that women should desire. Many apps describe focus on working on various body parts separately, what could also perpetuate discourses perceiving the female body as fragmented rather than a cohesive whole, encouraging further scrutiny of body parts. The ideal presented with the use of the apps’ language advertises not only an unrealistic figure type, but also establishes an idea that health is an ongoing, yet unfinished project. The fitness apps blur the line between beauty and health (Cairns and Johnston 171).

The icons of these apps predominantly present white women implying whiteness as part of the norm defining health, although promoting “Brazilian buttocks”as one of the goals. Moreover, the apps advocate youth by routinely depicting young women on the icons, framing youth as the privileged result. Consequently, the idealized “healthy”female body promoted through the fitness apps is mostly white, young and slim, yet busty with a well-shaped bottom (Doshi 189).

From an analytic perspective, this ideal presents how fitness apps perpetuate traditional ideas of healthy female body while encouraging women to internalize these ideas through the supposed rhetoric of choice at the same time that in the end leads to Foucauldian docile body. This means that women have a choice whether to use the apps, however, the implication of thin, bikini-ready body is presented as something what women desire (Cairns and Johnston 154).

SWEAT

Kayla Itsines’app follows the general idea of fitness apps through focusing on “flexibility, variety and support when working towards health and fitness goals”(SWEAT). There are four workout programs including: the flag program, Bikini Body Guide, yoga and SELF post-pregnancy guide. The user can choose from a variety of workouts that take up to twelve weeks and are comprehended by a nutrition plan.

The interface is easy in use with sections such as “workouts”, “food”, “activity”, “community”and “progress”. Hence, in addition to the ideal body image, that is established through the Bikini Body Guide, SWEAT conceptualizes the healthy woman as an entrepreneur, a person combining hard work and risk to achieve success by actually encouraging women to engage in self-surveillance and self-advocacy (Lupton 236; Sanders 38. The body becomes an entrepreneurial project involving constant monitoring to achieve success (Doshi 193), where using social media networks as a form of motivation and emotional support, further entrenches the narrow versions of healthy bodies. Such creation of “body projects”through community building do (Brumberg 97), in fact, provide women with support and shows how technological affordances can provide access to a fitness management resource. However, one of the risks is that the dependence on such networks is tied to the presence of the app itself with a pressure to share and celebrate fitness journeys.

“Love yourself”

This analysis discusses the ways the fitness apps directed at women are presented in the app store and the possible outcomes in the context of being “health”apps through gendered conceptualizations about healthy bodies. The project’s “intervention”in the issue has resulted in creating an app prototype by using the affordances of apps such as SWEAT to make it more open to all “women”types, although the project acknowledges the complexity of women’s experiences and the fact that it would be impossible to create an app that would not exclude anyone in some way. Nevertheless, our alternative app tries to include subjective experiences of health by acknowledging the lived experiences and, hence, fitness, leading to broader conceptualization of women’s health without reducing the focus on standardized body size and exploring more body positive approach.

Conclusion

In today’s media female bodies are often portrayed as thin, white and well-shaped, which includes images in women fitness apps. This research has analyzed several fitness apps, among which the SWEAT app as its main case study. The application shows a perfect example of how female bodies are used commercially to get the application downloaded or its products sold. Apps like the SWEAT app give their users the idea they too can achieve bodies as shown by the apps by encouraging them with words like “slim down” and “lose weight”. Additionally, the SWEAT app provides users with a number of programs concerning workouts and nutrition plans to achieve their goals.

However, many of the body types shown in applications like the SWEAT app are not achievable to many women. In addition, these unrealistic images even cause women to get more dissatisfied with their bodies. Therefore, this research has analyzed four fitness applications with a more neutral perspective towards human bodies, such as Evolve 21, by using the walkthrough method by Light et al. These apps focus more on the function of the body rather than its presentation, for instance, these apps focus more on the body being healthy enough to run a certain period. This idea contrasts with the idea of fitness apps explicitly designed for female consumers impose as those mainly focus on women their physical conditions in a way that draws from socially constructed femininity ideals.

By analyzing four fitness apps with a more neutral approach, this research created a prototype for a new, more realistic and even-handed female fitness application, including elements of the four evaluated applications and research on the topic. Furthermore, the prototype left out the commonly used pink and white “feminine” nuances, as seen in women fitness applications as SWEAT. Additionally, to prevent women from comparing their bodies to unrealistic human bodies portrayed by an app, avatars are used wherever a human is portrayed. Moreover, this application focuses more on the function of the body as seen in the more neutral applications analyzed, because a healthy body is does not necessarily have to do with the way it looks.

Health Centre Prototype

Work Cited

Barriga, Claudia A., Shapiro, Michael A., Jhaveri, Rayna. “Media Context, Female Body Size and Perceived Realism.” Sex Roles. 60 (2009): 128-141

Brumberg, Joan Jacobs. The body project: An intimate history of American girls. Vintage, 1998.

Cairns, Kate Josee Johnston. “Choosing health: Embodied neoliberalism, postfeminism, and the “do-diet””.Theory and Society, vol. 44, no. 2, 2015, pp. 153-175, doi: 10.1007/s11186-015-9242-y

Depper, Annaleise, Howe, David. “Are we fit yet? English adolescent girls’ experiences of health and fitness apps.” Health Socialogy Review. 26 (1) (2017): 98-112.

Doshi, Marissa J. (2018) “Barbies, Goddesses, and Entrepreneurs: Discourses of Gendered

Digital Embodimen in Women’s Health Apps. Women’s Studies in Communication, vol. 41, no. 2, 2018, pp. 183-203: doi:10.1080/07491409.2018.1463930.

Foucault, Michel. “The Meshes of Power”. Crampton, Jeremy W., Stuart Elden Space, Knowledge and Power: Foucault and Geography. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2007, pp. 153-162.

Guerra E., Storia e cultura politica delle donne, Archetipolibri, Bologna, 2008.

Light, Ben, Burgess, Jean, Duguay, Stefanie. “The walkthrough method: An approach to the study of apps.”New Media & Society. (2016): 1-20.

Lupton, Deborah. “M-health and health promotion: The digital cyborg and surveillance society”. Social Theory & Health, vol. 10, no. 3, 2012, pp. 229-244, doi: 10.1057/sth.2012.6.

Martin, Kimerly Embacher, McGloin, Rory, Atkin, David. “Body dissatisfaction, neuroticism, and female sex as predictors of calorie-tracking app use amongst college students.” Journal of American College Health. 66:7 (2018): 608-616.

Noble, Safiya Umoja. “Algorithms of Oppression. How Search Engines Reinforce Racism.” New York, United States: NYU Press, 2018.

Sanders, Rachel. “Self-tracking in the digital era: Biopower, patriarchy, and the new biometric body projects”. Body & Society, vol. 23, no. 1, 2017, pp. 36-63, doi: 1357034X16660366.

Wachter-Boettcher S., Technically Wrong: Sexist Apps, Biased Algorithms, and Other Threats of Toxic Tech, W. W. Norton & Company, 2017.

Weingus, Leigh. “Inside The Body Image Movement That Doesn’t Focus On Your

Appearance.” HuffPost. -08-15T12:46:57Z 2018. Web. Oct 22, 2019 https://www.huffpost.com/entry/what-is-body neutrality_n_5b61d8f9e4b0de86f49d31b4

Wolchover, Natalie. “Why Is Pink for Girls and Blue for Boys?” livescience.com. 1 August, 2012. Web. Oct 24, 2019 <https://www.livescience.com/22037-pink-girls-blue-boys.html>.

Workout Apps by 7M. Workout for Women | Weight Loss Fitness App by 7M. 2017. Vers. 3.1.0.GooglePlay.https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=net.workoutinc.seven_7minutesfitness_forwomen&hl=pl.