From Liking to Consuming: the Liking Economy of Social Media

Have you ever imagined a world where your received Instagram likes can be directly exchanged into the same number of US dollars offline? You may think this sounds still pretty far away, but some artists have actually turned this scenario into reality by pricing artworks that received social media likes.

The “like” social button now carries strong social significance including impression management, identity construction, and maintenance of social ties online for individual user (Eranti & Lonkila, 2015). In economic terms, social media likes became an essential element in the emerging reputation-based cluster of business model, which power a growing share of Web-based companies (Gerlitz & Helmond, 2013; Eranti & Lonkila, 2015).

In other words, we have now entered an era of the liking economy.

“Money = Likes”

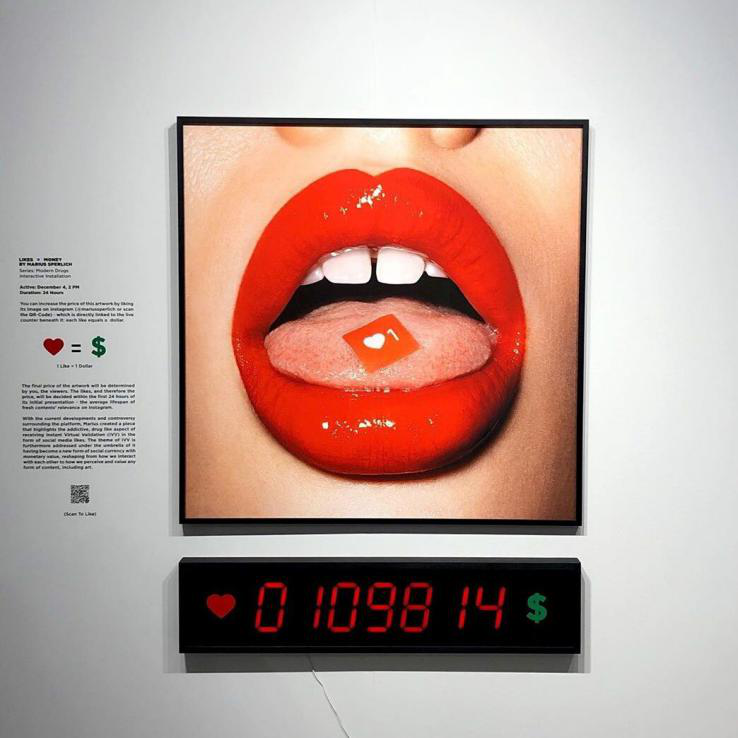

In the mid of September, Berlin photographer Marius Sperlich has launched one of his recent art projects in König Galerie Berlin, which is named as MODERN DRUGS PART II: “MONEY = LIKES”.

This interactive portrait consists of three essential parts. Namely, a close-up photo in which a dollar sticker is put on a girl’s tongue, an Instagram post featuring this photo on the artist’s account, and an electronic counter that restlessly counts the Instagram like number of the post. According to the artist, the artwork is priced off how many likes the post received on Instagram (Sperlich, 2020 September).

In this way, the electronic counter links the value of the artwork in physical world to the pre-defined communicative act of online liking from its Instagram audience.

The Liking Economy

This project is not just about how “likes” on social media platforms redefine the value of art in this online generation. Rather, it’s more about the commonly existing interdependency of social media likes and money, as well as its emotional impact on our society.

As Gerlitz and Helmond (2013) stated, the “like” as a social button, not only allows the instant transformation of user engagement into numbers on button counters, which can be traded and multiplied, but also function as tracking devices. Platforms therefore have empowered the ability of like buttons to be converted to revenue by quantifying and tracing the pre-defined communicative act of online liking (Veszelszki, 2018). In this sense, we have entered an era of the liking economy, where social media likes are given actual economic value.

In fact, the liking economy is becoming more and more obvious in our daily life. We have observed an explicit rise of influencer marketing since the launch of Instagram. Through donation, subscription, advertising collaboration and merchanization, YouTubers like PiewDiePie and Belle Delphine can generate a revenue and transform their received likes into offline currencies. The liking economy has seemingly brought an unprecedented and emerging form of labor and trade into the market. Yet the question is how this new “likes”-exchange-money business model is going to influence society.

Beyond “Likes”: A New Commodity as Spectacle

One of the social consequences of the liking economy is the unavoidable penetration of commodity logic in our life. As a participant of the Internet, we are clearly requested to interact and we all indulge ourselves in the pleasure of consumerism during the participation (Lovink, 2008 September). Arguably, the launch of the like button enhanced such a commodity logic of individuals’ online participation. The desire of being seen as an individual has never been this strong ever. We are so obsessed with liking or be liked online. We eagerly post our daily life on all kinds of social media and impatiently wait for the others to tap the like button for us. We are no longer the “anonymous and passive mass consuming the spectacle (Debord, 2013)” in Guy Debord’s work. We have entered a new spectacle society where we demand to be Internet spectacle on our own will. We commodify ourselves online.

Meanwhile, the like button, as an economic resource has shifted the meaning of friendship online. Our followers are not just our friends anymore. They are also our potential market, and their likes are the receipts for buying our online content. Such commercialization of friendship can be seen in the commonly existing move toward using friends as advertisements (Bucher, 2013). In this sense, we commodify our social relations online.

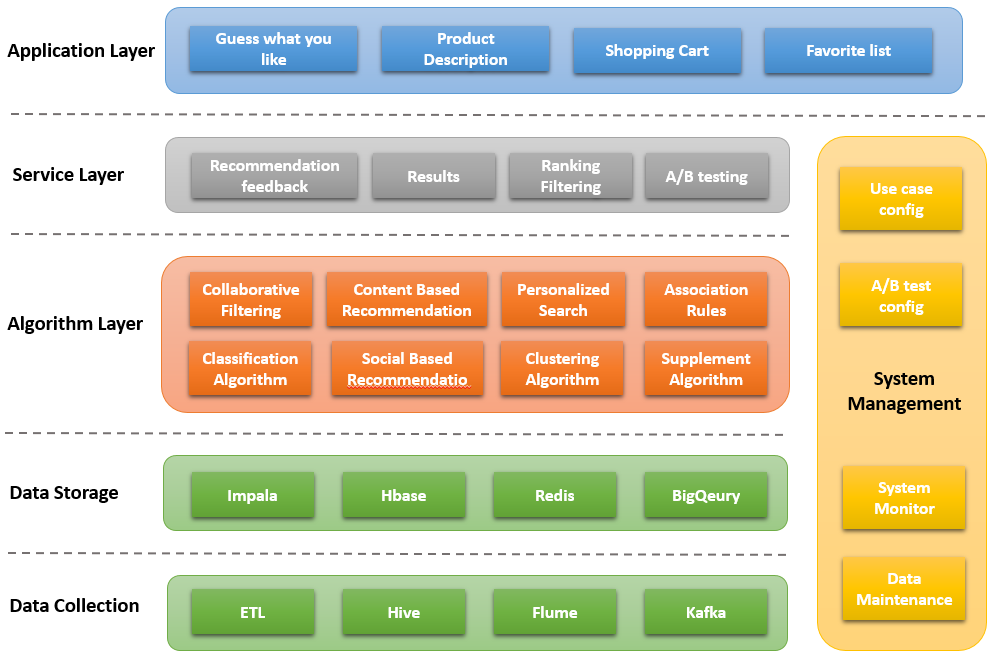

Algorithmic Moderation of “Likes”

While the “likes” on social media have enhanced the penetration of online commodity, an important factor that we tend to ignore is the existence of social media algorithms during this penetration. Social media content, including our likes, is also a part of the big data which is becoming more and more regulated by algorithms (Gorwa et al., 2020). The moment we tap on a like button, algorithms process and classify which content we are liking and then decide which content we may like as well. Platform algorithms educate us to like and produce content that fits in its purposes. In this way, social media algorithms moderate our commodity logic in this liking economy. This can also be seen as a part of social media platform governance in cultural practices (Nieborg & Poell, 2018). In this regard, none of us is sure about whether this algorithmic moderation can be called neutral.

Eventually, let’s get back to Marius Sperlich’s thought-provoking interactive portrait.

While “1 like=1 USD” is still a quite surreal social imagination for a lot of us, the liking economy behind this scenario may not be that far away from the reality that we are in right now.

And it is worthy to start thinking while tapping on a like button now: are we just liking it? Or…

References

air.jp. (2020, September 20). air.jp on Instagram: “JUST DROPPED SOME STUFF @associatedwithdeath.” Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/p/CFVFFZZDagF/

Azoulay, B. (2020, January 2). Meet The Berlin Photographer Using Instagram to Tell Provocative Stories. HYPEBEAST. https://hypebeast.com/2020/1/marius-sperlich-berlin-photographer-interview

Belle Delphine Store. (n.d.). Belle Delphine Store. Retrieved September 25, 2020, from https://www.belledelphinestore.com/

Bucher, T. (2013). The Friendship Assemblage: Investigating Programmed Sociality on Facebook. Television & New Media, 14(6), 479–493. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476412452800

Debord, G. (2013). The Commodity as Spectacle. In K. Knabb (Trans.), The Society of the spectacle (Paperbound edition, pp. 13–21). Bureau of Public Secrets.

Eranti, V., & Lonkila, M. (2015). The social significance of the Facebook Like button. First Monday. https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v20i6.5505

Gerlitz, C., & Helmond, A. (2013). The like economy: Social buttons and the data-intensive web. New Media & Society, 15(8), 1348–1365. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444812472322

Gorwa, R., Binns, R., & Katzenbach, C. (2020). Algorithmic content moderation: Technical and political challenges in the automation of platform governance. Big Data & Society, 7(1), 2053951719897945. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951719897945

Sperlich, M. (2020, September 8). “MODERN DRUGS PART II: „MONEY = LIKES“. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/p/CE4d8cBFOJy/

Lovink, G. (2008, September 5). The society of the query and the Googlization of our lives. Eurozine. https://www.eurozine.com/the-society-of-the-query-and-the-googlization-of-our-lives/

Nieborg, D. B., & Poell, T. (2018). The platformization of cultural production: Theorizing the contingent cultural commodity. New Media & Society, 20. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818769694

Veszelszki, Á. (2018). Like economy: What is the economic value of likes? Society and Economy, 40(3), 417–429. https://doi.org/10.1556/204.2018.40.3.8

Wang, C. (2020, June 7). Why TikTok made its user so obsessive? The AI Algorithm that got you hooked. Medium. https://towardsdatascience.com/why-tiktok-made-its-user-so-obsessive-the-ai-algorithm-that-got-you-hooked-7895bb1ab423