Bilibili: a media platform for young Chinese generation

Sunday, 27 September 2020, 12:34 CEST

A Brief Introduction

“Bilibili

is China’s biggest anime streaming site, as well as one of the country’s

biggest video-sharing sites” (Josh), “which derived from a Japanese

video-sharing website, Niconico” (Zhou 7). On the one hand, the core of

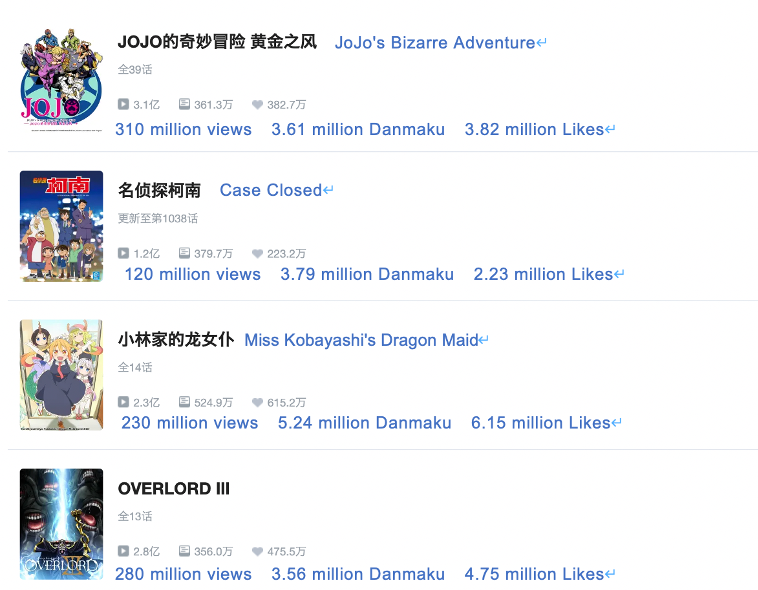

Bilibili, as its CEO stated, is ACG (anime, comics, and games) contents. More

than 1680 animations are displaying on this platform with many views. On the

other hand, it has similar functions with YouTube, which allows people not only

to watch videos, but also create and upload their videos. It is a

user-generated content video platform “with enhanced social features” (A.L. Jia

et al. 113). People who share their video on Bilibili are named “uploader”.

Their videos can be liked, shared, and added to the favourites by the

audiences.

Its targeted users are younger generations in China. In the speech of the manager of Bilibili, in the past three years, the average age of new users is 21 years old (Chen). It could attract so many young people not only because of the variety of animations. Moreover, there is no advertising when people watch videos on this website. Even though some particular programs or shows require audiences to be a member of Bilibili, most videos on this platform are free to watch without commercial contents.

Why it is emergent

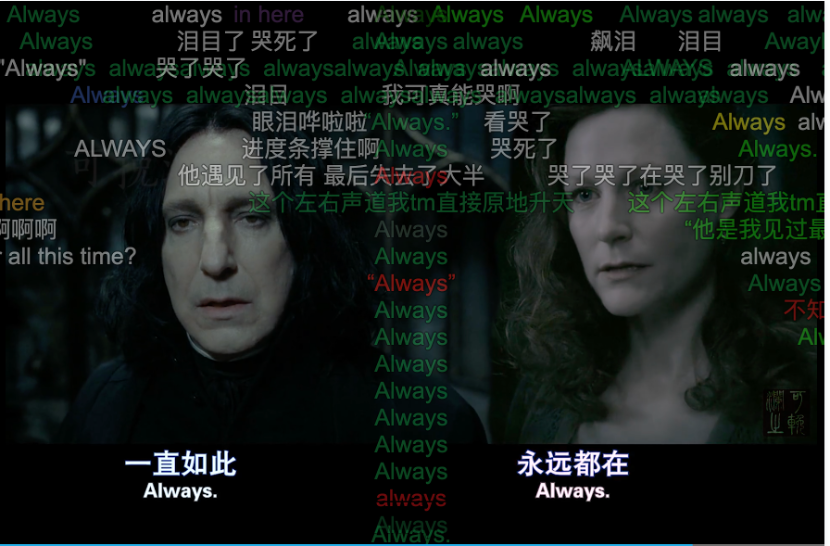

There are several characteristics which make Bilibili a new and young social media platform. First of all, the most significant function which made it a new media platform is Danmu (or named Danmaku). Danmu refers to “a system of superimposed comments running across the screen from right to left as the video plays” (Zhang and Cassany 2). It is a relatively new thing in China which appears in the recent ten years. Unlike traditional way of commenting below the videos, Danmu are “live” comments, and they move from one side to another during video playback, which allows the viewers to “interact” with other spectators and being accompanied by others while watching a video.

There are other functions of Danmu; one can send a brief introduction of a director or the actors, which help other viewers to gain more knowledge and information when they watch a film (Zhang and Cassany). What’s more, there are many people reprint YouTube videos to Bilibili since China banned YouTube. As some of those videos have no translations, viewers then can make a live translation available for others via Danmu, which is a benefit to others who may not understand the original language of the video. According to Zhang and Cassany (20), Danmu “allows users to connect, interact and share their content in an informal, self-regulated and multimodal learning community”. And it helped to build participatory culture, that “people work together to collectively classify, organise, and build information” (Delwiche and Henderson 3).

Secondly, as a user-generated content website, it emphasises on the participation, value and control of users (Yan et al.). Other than sharing video, it also allows users to follow uploaders they like to keep their information updated. Moreover, “like” is not the only way to present audiences’ support, users can appreciate uploaders’ contribution via virtual money donations (A.L. Jia et al.). Although it has these unique functions comparing to other video platforms in China, Bilibili is still a non-mainstream video website with fewer users. According to Graziani, “China’s online video market seems to be dominated by 3 companies: Youku, iQiyi and QQ Video.” Simultaneously, compared to YouTube, video uploaders on Bilibili are mostly Chinese, while YouTube provides “80 different language options, local versions in 91 countries” (ChannelMeter). Consequently, Bilibili is an emergent website but still used by limited groups of users.

What are the debates

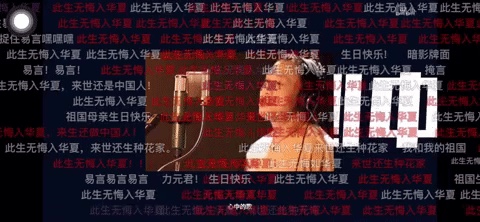

Danmu is a ubiquity way of communicating with others on Bilibili, and it has various colours which can provide a visual shock to the spectators. This function then becomes a way for fans to support their favourite celebrities, movies, and so on. Chinese authorities have found such uniqueness and made it a tool for them to have more in-depth communication with young Chinese generations, as well as put forward their ideology to the users. By researching on Biliob (a website aims to collect and observe data of uploaders on Bilibili), Chinese Communist Youth League (CCYL) opened an official channel and has more than 7 million fans with videos gained over 1.2 billion views in total. The third most viewed video published by CCYL is a music video in which 102 uploaders from Bilibili singing My People, My Country to celebrate the National Day of China. All the uploaders from this MV have millions of followers which proved their popularity.

Figure 1

Inviting them to sing this song also means that there will be millions of viewers and will have a considerable impact. Figure 1 is a screenshot of the video, and there are lots of red danmu. Red is the primary colour of the Chinese national flag and symbolised China. The translation of those Danmu is “I am a Chinese, and I will not regret it in this life, and I want to be a Chinese in the next life”. The video and its supporting Danmu can arise the audiences’ nationalism by creating “an emotional association with youth” (Pan 156), thus “embed ‘political leading’ in this internet jungle” (Pan 140). Besides, CCYL took advantage of Bilibili, that animation related videos always being highly focused, it cooperated with an uploader and published a funny commentary to animation to satirise Donald Trump. Here, CCYL is using the most acceptable way for Bilibili users to instil their ideology. It can be argued that CCYL is “decorating the regular propaganda into a “lovely” play rich in current fashion of sub-cultural style” (Pan152). By integrating itself more into the environment of Bilibili, CCYL could have more opportunities to guide the opinions of young people in China and strengthen their ideology. Consequently, Bilibili is not just a platform for video uploaders and users to communicate, it has also become a tool that government can use to find the preferences of the younger generation and control their thoughts from a political perspective.

To sum up, as an emerging media platform, it has lots of active users creating and sharing their experiences in different fields. Danmu is its most prominent feature and most significant advantage. The authorities in China have seen the tremendous impact that Bilibili has had on young people, therefore they utilised it as a tool to operate propaganda and promoting the government and make them “love” the country.

Bibliography

ChannelMeter. “YouTube’s Top Countries.” Medium, Medium, 4 Mar. 2019, medium.com/@ChannelMeter/youtubes-top-countries-47b0d26dded. September 26, 2020.

Graziani, Thomas. “What Is Bilibili? A Look into One of China’s Largest Online Video Platforms.” WalktheChat, 16 June 2019, https://walkthechat.com/what-is-bilibili-a-look-into-one-of-chinas-largest-online-video-platforms/. September 26, 2020.

Jia, Adele Lu et al. “Predicting the Implicit and The Explicit Video Popularity In A User Generated Content Site With Enhanced Social Features”. Computer Networks, vol 140, 2018, pp. 112-125. Elsevier BV, doi:10.1016/j.comnet.2018.05.004.

Pan, Nini. “The Mobilization of Cyber-Nationalism by the Communist Youth League: Pressure, Opportunity and Strategy.” Journal of Asia-Pacific Studies (Waseda University), 2018, pp. 139-156

Yan, Li, et al. “Video Diffusion in User-generated Content Website: An empirical analysis of Bilibili.” 2019 21st International Conference on Advanced Communication Technology (ICACT). IEEE, 2019.

Ye, Josh. “Bilibili, China’s Biggest Anime Site, Covers the Screen in User Comments.” South China Morning Post, 20 Sept. 2019, www.scmp.com/abacus/who-what/what/article/3028230/bilibili-chinas-biggest-anime-site-covers-screen-user-comments. September 26, 2020.

Zhang, Leticia-Tian, and Daniel Cassany. “Making Sense of Danmu: Coherence in Massive Anonymous Chats On Bilibili.Com”. Discourse Studies, vol 22, no. 4, 2020, pp. 483-502. SAGE Publications, doi:10.1177/1461445620940051.

Zhang, Leticia-Tian, and Daniel Cassany. “The ‘Danmu’ Phenomenon and Media Participation: Intercultural Understanding and Language Learning Through ‘The Ministry Of Time’”. Comunicar, vol 27, no. 58, 2019, pp. 19-29. Grupo Comunicar, doi:10.3916/c58-2019-02.

Zhou, Qiyang. “Understanding User Behaviors of Creative Practice on Short Video Sharing Platforms – A Case Study of TikTok and Bilibili.” Electronic Thesis or Dissertation. University of Cincinnati, 2019. OhioLINK Electronic Theses and Dissertations Center. September 26, 2020.