Covid-19 Contact Tracing Apps: a Threat or a Solution?

The year of 2020 is definitely not what we, as a global community, were expecting. Due to the emergence of the Covid-19 virus, later categorized as a pandemic, our daily lives and routines have changed, and our priorities have shifted. In these unprecedented times, our focus is no longer on our individual tasks and goals but on a global and universal fight for survival. In this new era, researchers all over the world, are coming up with ideas and inventions to slow the spread of the virus and have better control on the situation. The Covid-19 pandemic has influenced a new wave of technological advancements including Contact Tracing Apps. But with this innovation, we have observed a rise in concerns about citizens’ data protection and privacy, and a fundamental question; Is our collective survival more important than our individual freedom?

How do contact tracing apps work?

The Information Commissioner’s Office had defined the contact tracing apps as ”considered to be a mobile application which functions to notify users when they have been in recent proximity with another user who has confirmed symptoms of COVID- 19 (whether via official or self-diagnosis). It uses ‘proximity data’ which consists of identifiers broadcast by pairs of devices that have been close to each other (possibly including how close they were, and for how long).” (ICO 2)

What seemed like an efficient idea turned out to be more complicated than anticipated. Following the rise in Covid-19 cases all over the world, multiple countries have turned to contact tracing apps to control the situation. In most cases, these apps were developed by the governments themselves, while others turned to private developers like Canada and Finland, but for every app created, more and more people started voicing their concerns regarding the protection of their data and the threat to their privacy.

In an effort to prevent these concerns from becoming real issues, Amnesty International, with more than 100 other organizations, have published a statement that ”the use of digital surveillance technologies to fight pandemic must respect human rights” (Amnesty). The American Civil Liberties Union has followed in the same path by publishing the Principles for Technology-Assisted Contact-Tracing. These documents share similar goals for these apps such as voluntary participation, privacy-preserving, data minimization, and a guarantee of no data leakage.

Privacy threats and issues

We know that ”Big Data is seen as a powerful tool to address various societal ills, offering the potential of new insights into areas as diverse as cancer research, terrorism, and climate change. [But] On the other, Big Data is seen as a troubling manifestation of Big Brother, enabling invasions of privacy, decreased civil freedoms, and increased state and corporate control. (Boyd and Crawford; 663-664; 2012)” And despite the efforts made by NGOs and governments to preserve citizens’ freedom and privacy intact, many issues have come up. One of the biggest threats encountered is how these apps open the door to unethical mass surveillance. Indeed, with many of the users giving consent and access to the apps, it has become easier for governments to track and surveil citizens using the data collected directly from them, the data collected by their phone operators, and in some cases, by including geo-locators in the app. The use of a centralized location to store the data has also caused people to panic as it can easily be hacked. Many experts have suggested to decentralize the data and store it in many different places, such as people’s phones (Nature; 2020). Furthermore, most of the apps require the users to keep their Bluetooth on at all time, a practice that ”has a history of security breaches” (Nature; 2020). Users are left exposed to hacks, data theft, or phone invasion (Qureshi; 2019).

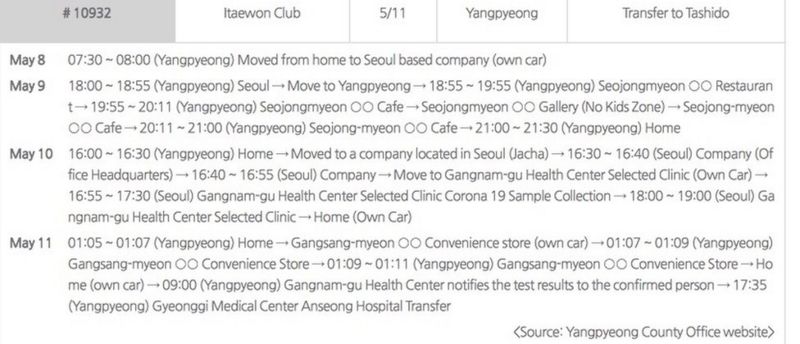

Case study: South Korea

Many of these issues were met when the South Korean government released its contact tracing app. By using GPS tracking, mobile operator’s phone location logs, credit and debit card transactions, and videos taken by the country’s surveillance cameras, the South Korean government created a state where everyone’s actions and movements were tracked and captured in order to retrace their steps in case of contamination. But the issue here, other than the government having access to all this data, is that the data is then published online with each citizen having an anonymous case number. In many instances, people were able be to identified based on the data shared by the government which has led to legal sanctions, as well as interpersonal issues, leaks of personal information, and public shaming. A study conducted by Rocher, Hendrickx, and Montjoye, Estimating the success of re-identifications in incomplete datasets using generative models showed that 99.98% of people would be correctly re-identified in any dataset using 15 demographic attributes. With South Korea releasing information on citizens’ every movement, this task became even simpler.

Contact tracing apps in the current debate about data privacy and protection

With the emergence of Big Data, we have witnessed a rise in concerns over our online privacy and protection. Until now, these concerns were mostly targeting companies who were collecting our data, and the lack of laws by governments ”it was easier to understand the ways that data was collected about us, first through the institutions and practices of governmentality—the census, the department of motor vehicles, voter registration—and then through the institutions and practices of consumer culture, such as the surveys which told us who we were, the polls which predicted who we’d elect, and the ratings which measured how our attention was being directed. (Gitelman; 2)”. As contact tracing apps become the norm in many countries, we have to question the ethical dilemma that accompanies their release. From a legal standpoint, these apps follow the newly established laws dictated by their countries, but are they ethical? The general legal consensus around data protection is that the data can be kept for no longer than necessary for the purpose of their collection (Voss; 2016). But in these times, no one can offer or predict a timeframe, which could lead to citizens’ data being collected and kept for longer than needed.

Can we, or more precisely, should we, trust our governments with such intrusive data? Is our collective survival and well being more important than our freedom? I believe that in these unprecedented times, this debate is no longer about the protection of our data and our privacy but mostly about how far we should go as nations to physically protect ourselves and our health.

References:

Amnesty International. Joint Civil Society Statement: States Use of Digital Surveillance Technologies to Fight Pandemic Must Respect Human Rights. 2 Apr. 2020.

Boyd, Danah, and Kate Crawford. “CRITICAL QUESTIONS FOR BIG DATA.” Information, Communication & Society, vol. 15, no. 5, June 2012, pp. 662–679, 10.1080/1369118x.2012.678878.

Cellan-Jones, Rory. “Tech Tent: What Can We Learn from South Korea?” BBC News, 15 May 2020, www.bbc.com/news/technology-52681464.

“Contact Tracing Apps: A New World for Data Privacy.” Https://Www.Nortonrosefulbright.Com/En-Nl/Knowledge/Publications, July 2020, www.nortonrosefulbright.com/en-nl/knowledge/publications/d7a9a296/contact-tracing-apps-a-new-world-for-data-privacy#France.

“Coronavirus Privacy: Are South Korea’s Alerts Too Revealing?” BBC News, 5 Mar. 2020, www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-51733145.

Council of Europe. “Contact Tracing Apps.” Council of Europe, www.coe.int/en/web/data-protection/contact-tracing-apps.

Gillmor, Daniel. “Principles for Technology-Assisted Contact-Tracing.” American Civil Liberties Union, 16 Apr. 2020.

Gitelman, Lisa. ” Raw Data ” Is an Oxymoron.

Hautala, Laura. “COVID-19 Contact Tracing Apps Create Privacy Pitfalls around the World.” CNET, 8 Aug. 2020, www.cnet.com/news/covid-contact-tracing-apps-bring-privacy-pitfalls-around-the-world/.

Information Commissioner’s Office. COVID-19 Contact Tracing: Data Protection Expectations on App Development. ICO.

Ng, Alfred. “Location Data Used for Tracking COVID-19 Has Its Limits, ACLU Warns.” CNET, 8 Apr. 2020, www.cnet.com/health/location-data-used-for-tracking-covid-19-has-its-limits-aclu-warns/.

Park, Sangchul, et al. “Information Technology–Based Tracing Strategy in Response to COVID-19 in South Korea—Privacy Controversies.” JAMA, 23 Apr. 2020, 10.1001/jama.2020.6602. Accessed 25 Apr. 2020.

Qureshi, Annie. “4 Ways Big Data Has Made Bluetooth A Terrifying Security Risk.” SmartData Collective, 15 May 2019, www.smartdatacollective.com/4-ways-big-data-has-made-bluetooth-terrifying-security-risk/.

Rocher, Luc, et al. “Estimating the Success of Re-Identifications in Incomplete Datasets Using Generative Models.” Nature Communications, vol. 10, no. 1, 23 July 2019, 10.1038/s41467-019-10933-3.

“Show Evidence That Apps for COVID-19 Contact-Tracing Are Secure and Effective.” Nature, vol. 580, no. 7805, Apr. 2020, pp. 563–563, 10.1038/d41586-020-01264-1.

Voss, Gregory W. “European Union Data Privacy Law Reform: General Data Protection Regulation, Privacy Shield, and the Right to Delisting.” Business Lawyer, vol. 72, no. 1, 2016.