Draw me like one of your French boys

Activism against online sexual harassment

As the digital era has made former consumers into prosumers; creating, editing, liking, disliking, saving and sharing content around the clock, life’s perks and detriments have mutated into the online realm too. With the presence and constantly increasing amount of visually based social media platforms, a lot of life’s challenges have become only more challenging. One of the downsides that social media platforms have inflicted, is the increase of sexual harassment and the new possibilities for voyeurism (Mandau 2020). Yet, as the online community has shown time after time, new problems call for new solutions.

Dick Pics on Blast

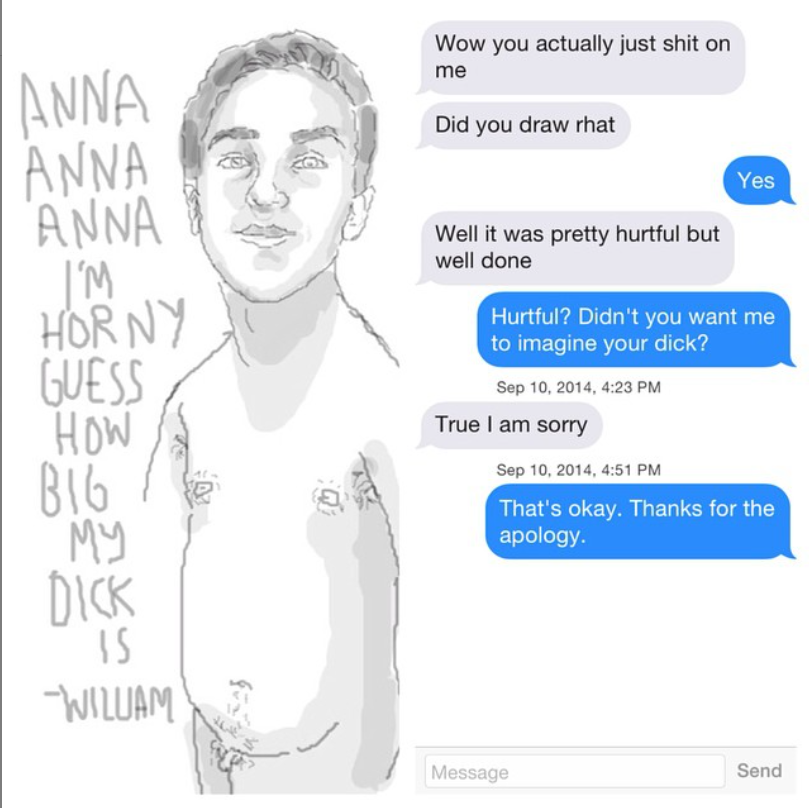

A great example of creative and appropriate reaction to online sexual harassment, was put forward by Anna Gensler on her Instagram account @Instagranniepants. As her bio briefly summarizes: “Objectifying men who objectify women in 3 easy steps: Man sends crude line via internet. Draw him naked. Send portrait to lucky man, enjoy results.” She found a rather humoristic manner to openly, yet so fittingly, repulse those men who think that women on online platforms post content for their filthy minds to thrive on. In particular those men who take their voyeurism to the next level by sliding in DM’s and enunciating their desires in often not so decent fashion. By drawing pictures of the harassers, she goes beyond just disclosing them to the online community, which has given her lots of positive attention (Vitis and Gilmour 2017). She has a following over 30.000, and while this might seem slim in comparison to the numbers of many influencers out there, it is substantial for an account that’s solely focussed on online resistance.

Anna might be one of the early adapters and certainly one of the most creative ones, as many perv-shame-accounts have been created on Instagram in the last couple of years. The majority of which is straightforward in its format; screenshot the DM’s, screenshot the profile picture (preferably a picture with wife or kids), edit and post. While these accounts are less creative, they do contribute substantially to the battle against online abuse and unsolicited male behaviour (Vitis and Gilmour 2017).

Critiquemydickpic,

Some users of Tumblr have also found new and taboo-breaking ways to “deflate the sexual threat of the dick pic”. On the page critiquemydickpic, users try to reconfigure the sexual aggression of the conventional dick pic and their normative feminist responses. In contrast to unsolicited dick pics, as many women receive on a regular basis, this page offers space to queer people who desire to open up and prioritise the desires of the viewer of the penis as artistic creations. As such it opens space for a more humorous and less threatening relationship with dick pics (Ringrose and Lawrence 2018). While the images can still be quite explicit, the affordances of the platform only make it possible for users to consciously visit the pages, by a disclaimer for explicit content, thus the images can’t be regarded as offensive. There seem to be very little requirements for contributions, resulting in a wide array of “dick pics”. The pictures do not even always include “real” dicks and when they do, it is indeed in a staged and deliberate manner that is miles away from the conventional dick pic. The humour included in many contributions and the receptive spectators do actually reconfigure the heteronormative power relationship and give a different perspective to the phallus (Ringrose and Lawrence 2018). By doing so critiquemydickpic seems to fulfil its promise to deflate the sexual threat of the dick pic, offering a new and fun fashion of online resistance.

http://critiquemydickpic.tumblr.com/

#Mencallmethings

On other, more mature, platforms like Twitter, there is a longer tradition of women trying to stand up to sexual harassment. For example the #mencallmethings campaign was one of the first effective feminist movements in the battle against female oppression in the online public sphere (Megarry 2014). The campaign enabled women to share their bad experiences, which led to a better overall picture of the scale on which women are confronted with online harassment. The hashtag indicated that the threatening abuse women receive online impedes their freedom of expression and often causes them to modify their own behaviours in response (Megarry 2014). Whilst this might seem like a obvious observation, the campaign did open a door to a new way of public unification for victims. The hashtag enabled and empowered women to share and collaborate, not only lowering the threshold for talking about harassment, but also formalizing the opposite stance against the patriarchy in the (online) public domain.

Apart from the contribution in the fight against the imbalance in patriarchy, the campaign also revealed an advantage for online harassment in comparison to its offline equivalent; it creates an online public record of women’s experiences (Megarry 2014). The affordances of the internet enable women to permanently document cases of harassment, taking away any doubt or interpretability of the concerning abuse. If and when legislation picks up the pace, this should simplify the criminal trial in the future, with clear and undeniable proof.

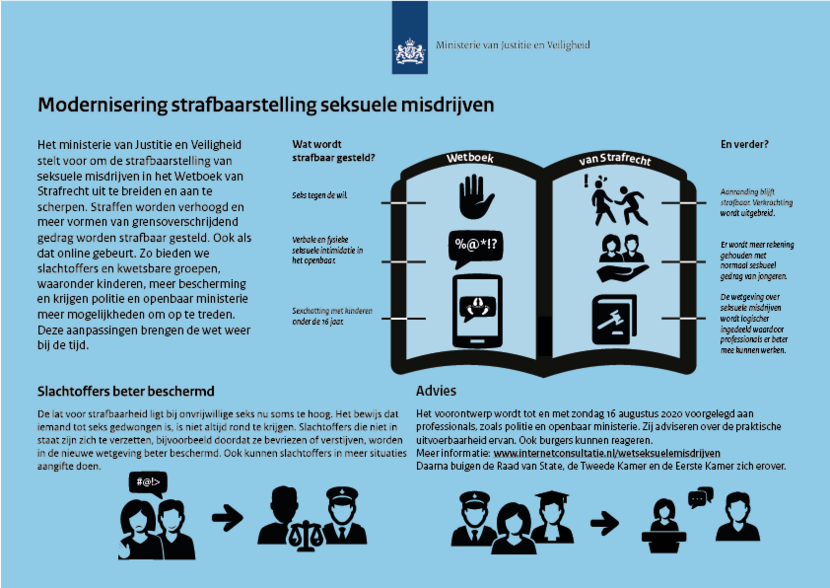

Legislation

Even though these new forms of online resistance are becoming more widely supported and the notion that women are passive victims in these cases is obsolete, the lack of applicable legislation is a major obstacle. This absence conserves a situation in which women are responsible and places the burden of managing harassment on the individual, to exclusion of the government or society (Milford 2015). The current COVID-19 pandemic has increased our social media usage and the current build-up of polarization in the public sphere, suggests a parallel increase in online abuse. While this might not mainly take shape in sexual harassment, the current remedies are inappropriate. Suggested measurements like blocking, muting and reporting do not tackle the ferocity, nor scale of the harassments (Vilk 2020). The problem, as for more of the online problems, seems to lie with liability. While social media platforms did take some measures by installing tools like the report buttons, the call for institutional measures and proper prosecution keeps on growing. There is hope though, as Dutch Minister of Justice Grapperhaus has filed a bill that judges online harassment equal to offline harassment (Veiligheid 2020).

References

Mandau, Morten Birk Hansen. 2020. ‘“Directly in Your Face”: A Qualitative Study on the Sending and Receiving of Unsolicited “Dick Pics” Among Young Adults’. Sexuality & Culture 24 (1): 72–93.

Megarry, Jessica. 2014. ‘Online incivility or sexual harassment? Conceptualising women’s experiences in the digital age’. In Women’s Studies International Forum, 47:46–55. Elsevier.

Milford T (2015) Revisiting cyberfeminism: Theory as a tool for understanding young women’s experiences. In: Bailey J and Steeves V (eds) eGirls, eCitizens. Ottowa: University of Ottowa Press, pp.55–82.

Ringrose, Jessica, en Emilie Lawrence. 2018. ‘Remixing misandry, manspreading, and dick pics: Networked feminist humour on Tumblr’. Feminist Media Studies 18 (4): 686–704.

Veiligheid, Ministerie van Justitie en. 2020. ‘Grapperhaus moderniseert wetgeving seksueel grensoverschrijdend gedrag – Nieuwsbericht – Rijksoverheid.nl’. Nieuwsbericht. Ministerie van Algemene Zaken. 12 mei 2020. https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/actueel/nieuws/2020/05/12/grapperhaus-moderniseert-wetgeving-seksueel-grensoverschrijdend-gedrag.

Vilk, Viktorya. 2020. ‘You’re Not Powerless in the Face of Online Harassment’. Harvard Business Review, 3 juni 2020. https://hbr.org/2020/06/youre-not-powerless-in-the-face-of-online-harassment.

Vitis, Laura, en Fairleigh Gilmour. 2017. ‘Dick pics on blast: A woman’s resistance to online sexual harassment using humour, art and Instagram’. Crime, media, culture 13 (3): 335–355.