The Dilemma of Prisoners on TikTok: An Analysis of the Implications of Dark Subcultures Online

By Alejandra O’Connor (oconnorale@hotmail.com), Li Shen (lshen141@gmail.com), Niall Manley

Abstract

This research study analyses the content of previously-seen, crime-related online content – such as Tumblr’s True Crime Community – exploring the implications of this type of content for young people, in particular. Following this, we outline a range of possible solutions to this phenomenon, and the ways in which TikTok can work to quell this trend before it leads to any dangerous consequences.

Introduction

Typically subcultures in the real world have been limited by space and time. However, the rise in internet usage and affordances offered by social media applications have allowed numerous subcultures to act trans-locally and enabled the existence of virtual subcultures dedicated to death, murder, and massacres (Raitanen and Oksanen 196). A new subculture has formed on TikTok dedicated to life in prison. The posts portray a pleasant prison life where inmates perform popular dances and teach their followers how they cook. As innocent as this may appear, when directly compared to a similar community on Tumblr, the True Crime Community, it can indicate possible dangers of the platformisation of crime. This research aims to analyse the phenomenon of dark subcultures online through content analysis and suggest possible solutions to this issue, as well as exploring the idea of responsibility as it pertains to deplatformisation.

Methodology

The methodology chosen to analyse this trend is a content analysis of previous case studies on the social media platform, Tumblr. The purpose of content analysis in the social sciences is to provide “predictions of future events” and to “get a sense of understanding about what causes events” (Riffe et al 20) and how to control such events. By choosing this qualitative method we are able to gain a deeper understanding of the cases by carefully examining and interpreting the stories, and attempting to identify patterns that can help us understand the consequences of internet subcultures further, which can then be used to foreshadow what could happen with the rising popularity of prisoners on TikTok.

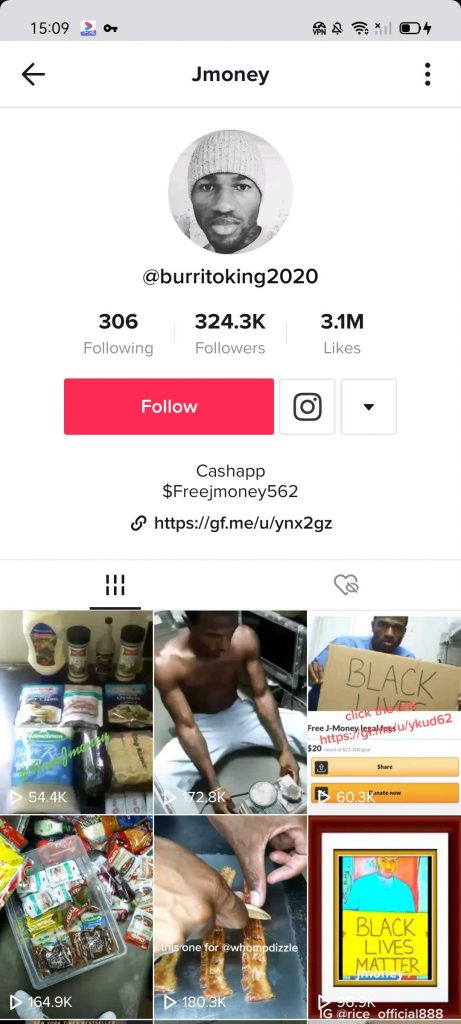

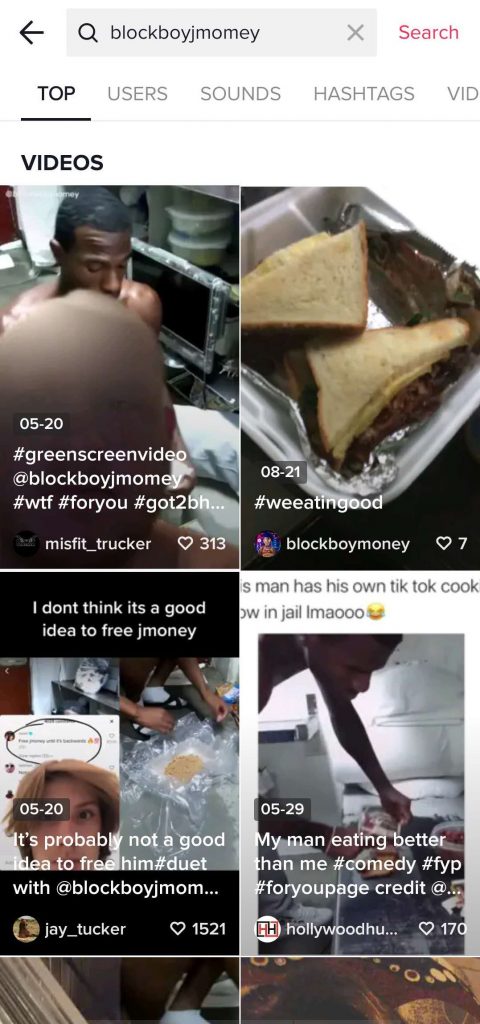

To do this we focused on the True Crime Community (TCC) of Tumblr and studiedcopy-cat cases of users in the community. We then analysed the content being published by popular accounts on TikTok, such as: @burritoking2020 and @coronakilla2020, as well as the comments left on their pages. From this we assessed the possibility of this subculture on TikTok mirroring that of Tumblr’s TCC, but with more dangerous implications due to TikTok’s younger demographic and the immediate communication followers have with prisoners.

The Importance of Studying TikTok

TikTok is known as a social media of freewheeling fun. Its higher tolerance and broad definition of “good content” do not exclude the dark sides of society, which emphasizes the replicating and sharing function (Tolentino). Phenomenally ranked the most downloaded app, this platform is characterized for its viral spreading format and addictive content, making it easier to trend (Tolentino).

The Importance of Studying Subcultures Online

Subcultures have been defined and studied since the mid 20th Century, with David Riesman distinguishing them from mainstream cultures saying a subculture “actively sought a minority style… and interpreted it in accordance with subversive values” (Middleton 155). Since then, subcultures have multiplied and diversified even further, with developments in technology and digital media heavily aiding this change and growth. To understand these alternative groups – and the psychological reasons for their birth – hence, it is important to study and examine them closely; to see, too, the potential effects and dangers of young people expressing themselves in ways and interests that veer from the norms of society today.

Platformisation of Crime and Their Fandoms

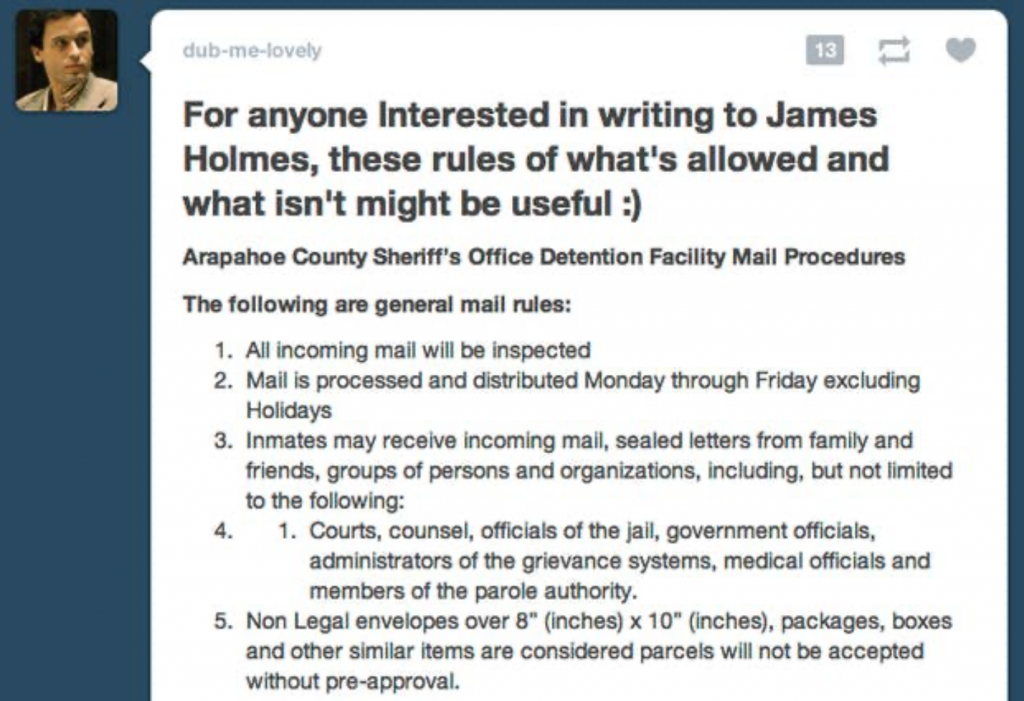

The platformisation of crime and their fandoms online has allowed users to be active prosumers, encouraging individuals to continuously edit, update, and comment (Raitanen and Oksanen). The difference between the idolisation of crime offline and online is that social media allows users to not just receive media messages passively, but rather re-create and circulate them online. This process then gives new meanings to this content and allows for circulation of new objects and ideas, like artwork and fanfiction (Raitanen and Oksanen 206). According to Naomi Barnes, recent studies conclude that media reports and coverage of homicides – including mass shootings – subsequently increase the occurrence of similar incidents among communities, “similar to the patterns seen in the spread of infectious disease” (43). She suggests that this study can be applied to the TCC, who spend hours creating and consuming violent and graphic material, leading them to be more likely to commit such crimes. Previously, the TCC organized letter writing campaigns, uploading guidelines for writing criminals like mass murderer James Holmes (see fig.1), who was responsible for the Colorado movie theatre shooting. However, now TikTok users can immediately reach out to criminals without the barrier of mail inspection and without needing to follow mailing formats or waiting months for a response.

Case Study: Tumblr’s True Crime Community

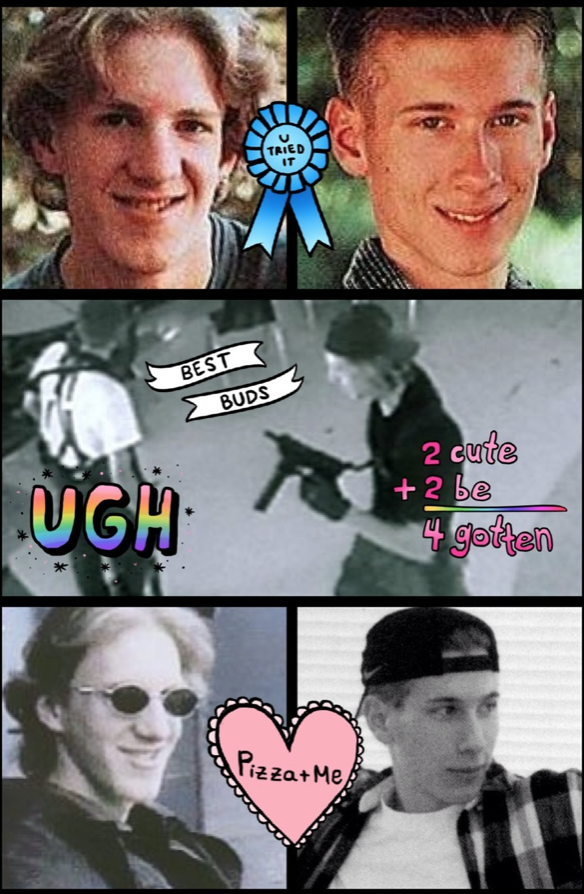

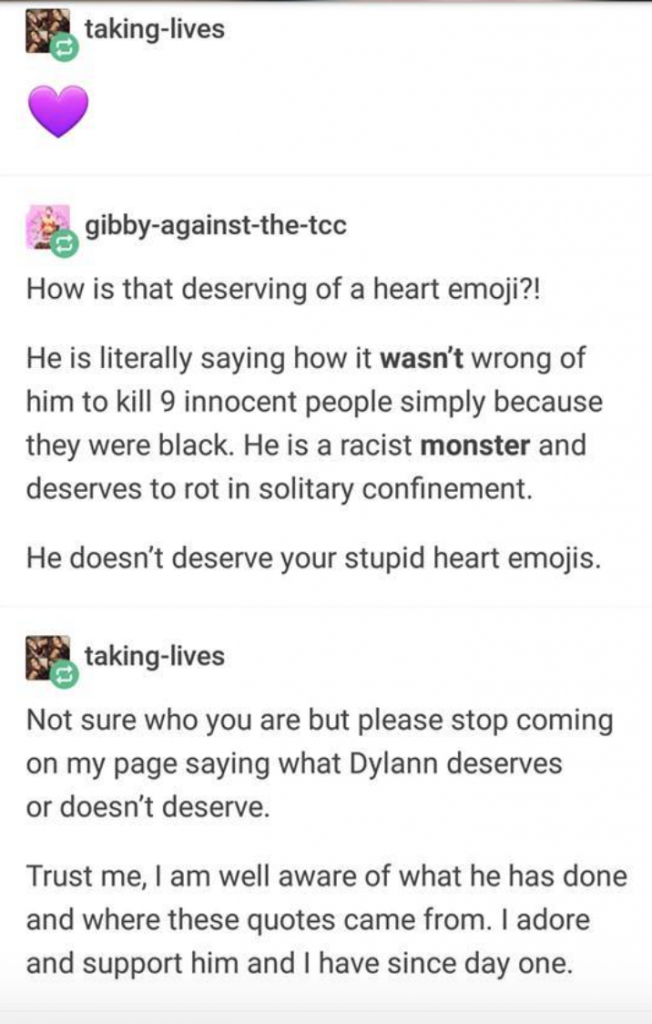

Tumblr is commonly known for “enabling the formation of counter-public spaces for marginalized millennial communities and progressives” (McCracken 151). Tumblr cultivated these subcultures as it gave people who were “labelled as weird or socially awkward a place to feel welcome” and share interests within groups of people who feel “othered” (Barnes 7). However, the affordance that enables communities to form and connect so easily has also assisted the development of niche groups, like the TCC. The community consists of people interested in criminology involving serial killers and mass murderers, and people who admire them (Beaumont), also known as hybristophilia, which is the sexual attraction towards people who have committed violent crimes (John). The community focuses largely on the Columbine shooters Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, and the white supremacist shooter Dylann Roof. Users post collages, art, jokes, fanfiction, etc. (see figs. 2&3) about these killers, stating things like they “wish they could comfort the killers before they go on trial” (Barnes 32).

The idolization of criminals usually stays online; However, it can spill over into the real world and have catastrophic consequences (Weill). One member of the community was Brein Basarich, who uploaded collages of notorious serial killers and called Roof “precious and handsome” (Weill). Basarich was recently arrested for planning her own shooting, posting her plans under the name “Taking-lives” (see figs. 4&5), where she posted her fantasies about marrying Roof (Farrell). Her charges were listed as “threats to kill, do bodily injury or conduct a mass shooting or an act of terrorism” (Farrell). Another member of the TCC was Adam Lanza, who was responsible for the Sandy Hook Elementary shooting in 2012. He constantly posted pictures and videos of mass shootings (Weill). Members of the community are repeatedly validating and glorifying killers; recirculating information about their crimes; keeping “the images fresh” helping to “foster an environment where a contagion factor is increasing the incidents” (Barnes 43); encouraging others among them to look for that same support from the community, leading them to commit copy-cat crimes. One positive aspect might be that most of the criminals idolized in the TCC community are now deceased and the majority of the fans were not alive when the crimes occurred. However, with the increase of convicted felons gaining access to TikTok, the immediate contact available to users can be seen as an issue that requires more attention.

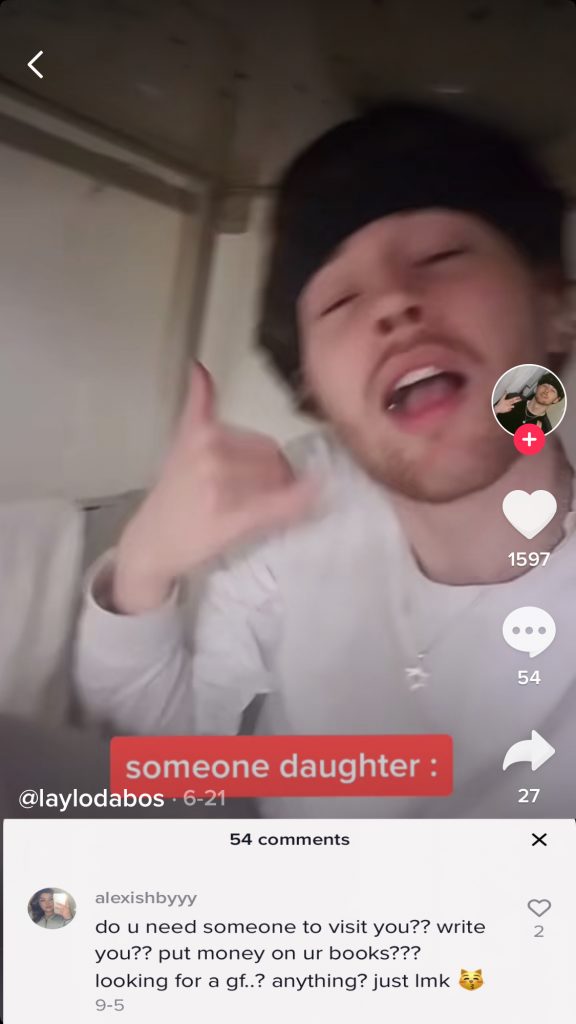

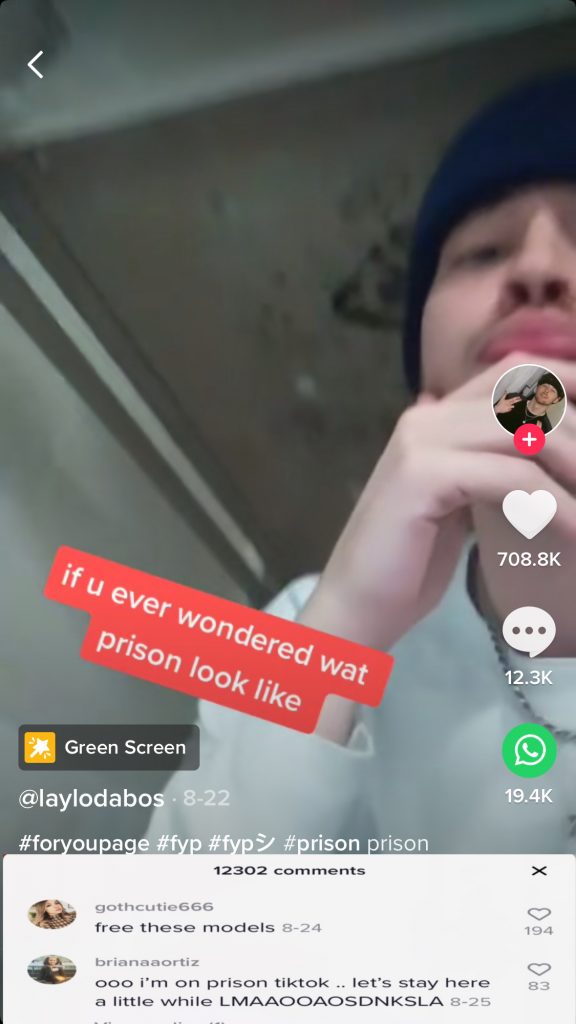

Tumblr’s TCC vs. TikTok’s #PrisonLife

According to an industry report, 43% of Tumblr users are from the age groups of 18-24 years old (Tumblr Statistics). In comparison, on TikTok, 69% of users are between the ages of 13-24 (20 Important TikTok Stats). These statistics showcase the young demographic on TikTok and why prisoners being popularized on this social media app can be dangerous. The rise of this subculture on TikTok mirrors the TCC as users have already begun idolizing the prisoners on the app by leaving comments showing their support on their posts (see figs. 6,7,8,9).

Retrieved from @Prisonbirkin on TikTok.

Retrieved from @Laylodabos on TikTok.

Analysis

Ethical Debate of Prisoners on TikTok

According to law professor Demetria Frank, the prisoner-to-public communication right has been argued as necessary to deal with the human right issue in the overcrowded prisons of the United States with relevant policies, which also includes the prisoners’ access to social media (143). The technological use of prisoners in many countries, such as Australia and Russia, has left us questioning whether access to personal social media accounts a human right is (Piacentini, and Katz; Kerr, and Willis). As Frank stated, this right should be designed to help the prison accountability, for prisoner rehabilitation, and to reduce jail population (147-150). However, social media platforms now provide more visibility and content of non-deliberative communication, which enables users to generate intimate relationships in virtual spaces (Piacentini, and Katz 186). The “electronic intimacy” in such social networking demands high frequency and earlier sharing of affection and intimate emotions, which paradoxically transforms private connection into open communication (Rosen 50). Therefore, in the case of the celebrity prisoners on TikTok, the convenience of producing intimacy contributes to idolizing criminals and involves the users into dark subcultures. With the decentralizing feature of TikTok reflected by its discouragement of building social networks among pre-existing contacts, private interaction between prisoners, and teenagers through TikTok is more separated and difficult to track (Tolentino). Simultaneously, criminal fandoms can be reorganized in the newly built social networking site through platform-based interactions (Poell et al. 8).

The communication patterns between prisoners and the public used to be more unidirectional because of technical limitations and now its gradually become more mutual shaping. The position of prisoner shifts from passive to active; their contents vary from mediaoriented to individual-oriented, which is against the principle of censoring public-to-prisoner and prisoner-to-prisoner approaches, thus raising new ethical problems (Frank 144).

For prisoners, social media platforms, like TikTok, have an effect similar to museums, as they beautify the shame of violating laws as prisoners’ fame (Ferguson, and Madill 415). Although much of the content released on prisoners’ TikTok accounts show the positive and socially integrated part of prison life, the social media access simultaneously empowers them with unfettered freedom to reach the public.

Jeron Combs, known as @burritoking2020, a celebrity prisoner still sitting out his sentence for murder, has successfully run a cooking channel on TikTok with 324,300 followers (see fig.10). One notable example from him is how he uses one iron bed frame as a griddle to cook burritos (Rodriguez-Jimenez). The behind-bar life on TikTok is presented as a pleasant vacation rather than a punishment, thus defusing the deterrent function of imprisonment and normalizing the concept of crime in public perception (Esposito 62). This leads other TikTok users to question the quality of prison life compared to that of law-abiding citizens (see fig.11). Are prisoners under the digital surveillance of the public or are they able to benefit and free themselves through social media?

Apart from the public unfairness, injustice for victim families, and the risks of weakening the authority of the prison system as an infrastructure to operate laws (Esposito 51), the ethical debate about teenage criminal fandoms become increasingly important as social media usage rises. According to Raitanen and Oksanen, school shooting fans centralizes amongst teenage girls, as one fluid category of this fandom present their admiration with sexual interest and romantic fantasy (196-201). Recent TikTok users applied this misleading and alluring intimacy by creating the hashtag #WriteAPrisoner to so-called “search for love” (Caldwell), thereby exacerbating the platformisation of this niche subculture

Moreover, due to the intense popularity of prison TikTok accounts, the TikTok recommendation algorithm will distribute more relevant content on the endless sliding interface under the “For You” column (Matsakis). Since the prominent visibility of such content is shaped by platform governance of data sorting, the recommendation expands the directions and possibilities of categorization, which means niche tastes of criminal content can widely point to the dark fandom on TikTok, algorithmically targeting teenagers and allowing dangerous interactions and the spreading of extreme ideologies (Bucher; Pasquale).

Implications and Solutions

Deplatforming is defined as removing one’s “access to a channel for delivering messages to an audience” (Rouse). This is predominantly a tactic used by social media companies to remove or restrict the exposure and power of so-called “dangerous individuals” on platforms (Rogers). Most notably, in 2019, Facebook removed the accounts of Louis Farrakhan, Alex Jones, and others on the claim they were a danger to society for their extremist ideologies (Wells). While opinions on the worthwhileness of deplatforming individuals vary, as discussed above, the issue of the platformisation of crime, specifically, would appear to be more clear-cut. Beyond what allowing prisoners access to spaces like TikTok does in terms of empowering them – and its blurring of the lines over whether or not they are in fact being “punished” for their past crimes – looking at previous related phenomena like Tumblr’s True Crime Community, giving voice to criminals and, to some degree, celebrating them can lead to disastrous consequences. Evidently, it is neither worth the risk to give prisoners use of TikTok nor has it been proven that it aids in their rehabilitation either; unlike permitting internet use for educational purposes (Champion & Edgar). Therefore, to avoid the threat of copycat crimes and the formation of intimate, one-to-one relationships between prisoners and susceptible young people; this trend must be stopped. The responsibility of this lies with the social media platforms themselves.

In the early 2010s, a similar trend appeared on the short-form video app Vine when one anonymous inmate, bearing the username @AcieBandage, in particular gained a sizable following on the app for showing his life inside of prison. This user’s account was effectively deplatfomed after his account was suspended (Knox et al.) Likewise, Tumblr changed its community guidelines in 2018 to explicitly ban all content glorifying violence, urging its users to report posts celebrating mass murderers and school shooters (Liao). Henceforth, TikTok must adopt similar measures to quell the celebrity of prisoners on its service.

Firstly, outright suspending the accounts of such content creators should form the bulk of their approach. Announcing to the public their intent to do so, and as well explaining the reasons why it is necessary to do so can inspire users to report relevant accounts, increasing TikTok’s potential to identify as many prisoner accounts as possible. Of course, TikTok cannot feasibly dedicate all of their manpower resources to this matter, so by combining this strategy with other techniques, they can work towards eradicating the source of this content completely. For example, if they do not see suspending all accounts to be achievable or the best solution, TikTok can “shadowban” certain popular accounts – heavily-limiting their exposure and ability to reach new users through hashtags, without directly removing the accounts (Seattle). With the ability to locate each newfound prisoner account immediately upon its creation essentially impossible, TikTok can make use of age-limiting content and reducing new prisoners growth potential from the outset – for instance, all content on popular hashtags like #WriteAPrisoner can be blocked from appearing on the accounts of users under the age of 18.

Furthermore, if TikTok can work with governments around the world and gain the power to do so, they can establish a policy whereby all TikTok content emitted from prison locations can be censored. This would involve prison internet networks to be secured by a firewall with no possibility for activity on TikTok to be broadcast and sent outside the walls of the prison (Benton Foundation). As well as, TikTok can work together with other social media companies to create a shared Firewall strategy to prevent the likes of Tumblr’s TCC and their own current prisoner trend to curtail any future communities from developing. Essentially, to deal with this phenomenon, it will take a range of approaches over a long period of time to lead to an eventual, effective deplatformisation strategy of crime-related content on both TikTok and elsewhere; as there is no immediate solution that will put an end to the online glorification of criminals. By acting now, however, TikTok can work towards a future whereby societies will not have to worry about the dangers of social media-inspired copycat crimes and the ilk someday soon in the future.

Conclusion

The importance of this topic lies on the impact of social media subcultures and how a seemingly innocent trend on these apps may lead to extremist opinions and actions. The research we conducted regarding this topic is only an introduction and does not entail the full scope of the issue. Nevertheless, it is important to analyse the dangerous of online activity through dark fandoms and potentially dangerous subcultures. Through the research conducted in this paper, we can conclude that the dark subculture of prisoners on TikTok can lead to the normalization of crime among young, impressionable users, which can result in copy-cat crimes, as previously seen with Tumblr’s TCC. The public-toprisoner communication on TikTok is barely restricted, which misguides teenagers through the recommendation algorithm and content of prisoners’ accounts. Digital intimacy builds dark fandoms regardless of ethical problems, which raises the reconsideration of the balance between human rights of prisoners and the legitimacy of social media’s role in public perception. By adopting policies of account suspension, shadowbanning, age limits, and content blocking by firewall, TikTok can work toward the essential deplatforming of prisoners that is needed to protect our society.

Works Cited

“Tumblr Statistics, User, Demographics and Facts For 2020”. Saas Scout (Formerly Softwarefindr), 2020. <https://saasscout.com/tumblr-statistics/> Accessed 15 October 2020.

“20 Important Tiktok Stats Marketers Need to Know In 2020”. Social Media Marketing & Management Dashboard, 2020. <https://blog.hootsuite.com/tiktok-stats/> Accessed 15 October 2020.

Barnes, Naomie. “Killer Fandoms Crime-Tripping & Identity in The True Crime Community”. All Graduate Plan B and Other Reports, 2015, <https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1725&context=gradreports> Accessed 13 October 2020.

Beaumont, Hillary. “Inside the World of Columbine-Obsessed Tumblr Bloggers”. Vice on the Internet, 2015. <https://www.vice.com/en/article/kwpd4n/speaking-to-columbiners-aboutdepression-suicide-and-the-halifax-shooting-plot-232.> Accessed 13 October 2020.

Broderick, Ryan. “A Guide to The Dark World of James Holmes Internet Fandom”. Buzzfeednews.Com, 2012. <https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/ryanhatesthis/a-guideto-the-dark-world-of-the-james-holmes-inte#.fybm8p3bpo> Accessed 14 October 2020.

Bucher, Taina. If… then: Algorithmic power and politics. Oxford University Press, 2018.

Caldwell, Jenna. “TikTok Teens Are Writing Prisoners in Search of Love”. Digital Trends on the Internet, 2020. <https://www.digitaltrends.com/features/tiktok-writeaprisoner-trend/>Accessed 14 October 2020.

Champion, Nina, and Edgar, Kimmett. Through the gateway: How computers transform rehabilitation. London: Prison Reform Trust.

Esposito, James L. “Virtual Freedom–Physical Confinement: An Analysis of Prisoner Use of the Internet.” New England Journal on Criminal and Civil Confinement, vol. 26, no. 1, Winter 2000, p. 39-66. HeinOnline.

Factora, Gisela. “A Deadly Obsession: Tumblr’S Fan Culture”. The Paw Print, 2014.<https://www.wrpawprint.com/opinions/2014/12/08/please-kill-tumblr> Accessed 16 Oct 2020.

Farrell, Paul. “Brein Basarich: Stripper Accused of Planning Mass Shooting”. Heavy on the Internet, 2019. <https://heavy.com/news/2019/01/brein-basarich/> Accessed 14 October 2020.

Ferguson, Matthew, and Devon Madill. “From shame to fame: ‘Celebrity’ prisoners and Canadian prison museums.” The Palgrave Handbook of Prison Tourism. Palgrave Macmillan, London, 2017. 415-434.

Frank, Demetria D. “Prisoner-to-Public Communication.” Brooklyn Law Review, vol. 84, no. 1, 2018, p. 115.

John, Arit. “How Tumblr’s True Crime Fandom Reacted to The Escape of a School Shooter”. The Atlantic, 2014. <https://www.theatlantic.com/culture/archive/2014/09/how-tumblrs-true-crime-fandom-reacted-to-the-escape-of-a-school-shooter/380124/> Accessed 14 October 2020.

Kerr, Aysha, and Matthew Willis. “Prisoner use of information and communications technology.” Trends and Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice, no. 560, 2018, p. 1.

Knox, George W., Etter, Gregg W., and Smith, Carter F. Gangs and Organized Crime. New York, NY: Routledge.

Liao, Shannon. “Tumblr Is Explicitly Banning Hate Speech, Posts That Celebrate School Shootings, And Revenge Porn”. The Verge on the Internet, 2018. <https://www.theverge.com/2018/8/27/17786584/tumblr-hate-speech-ban-school-shootingsrevenge-porn> Accessed 15 October 2020.

Matsakis, Louise. “Behind Bars, But Still Posting on Tiktok”. Wired on the Internet, 2020. <https://www.wired.com/story/prison-tiktok-behind-bars-still-posting/> Accessed 14 October 2020.

Middleton, Richard. Studying Popular Music. Open Univ. Press, 2010, p. 155. McCracken, Allison. “Tumblr Youth Subcultures and Media Engagement”. Cinema Journal, vol. 57, no. 1, 2017, pp. 151-161. Project Muse, doi:10.1353/cj.2017.0061.

Pasquale, Frank. The black box society. Harvard University Press, 2015.

Piacentini, Laura, and Elena Katz. “The Virtual Reality of Imprisonment: The Impact of Social Media on Prisoner Agency and Prison Structure in Russian Prisons.” Oñati Socio-Legal Series, vol. 8, no. 2, 2018, p. 183.

Raitanen, Jenni, and Atte Oksanen. “Global Online Subculture Surrounding School Shootings”. American Behavioral Scientist, vol 62, no. 2, 2018, pp. 195-209. SAGE Publications, doi:10.1177/0002764218755835. Accessed 15 October 2020.

Riffe, Daniel et al. Analyzing Media Messages. 4th ed., Routledge, 2019.

Rodriguez-Jimenez, Jorge. “Prisoner Starts His Own Cooking Show on TikTok And, Like, How”. We Are Mitú, 2020. <https://wearemitu.com/culture/prisoner-burrito-cookingshow-tiktok/> Accessed 14 October 2020.

Rogers, Richard. “Deplatforming: Following extreme Internet celebrities to Telegram and alternative social media.” European Journal of Communication, vol. 35, no. 3, 2020, pp. 213-229.

Rosen, Christine. “Electronic intimacy.” The Wilson Quarterly, vol. 36, no. 2, 2012, p. 48.

Rouse, Margaret. “What Is Deplatform? – Definition from Whatis.Com”. Whatis on the Internet, <https://whatis.techtarget.com/definition/deplatform> Accessed 15 October 2020.

Seattle, G.F. “What Is “Shadowbanning”?”. The Economist, 2018. <https://www.economist.com/the-economist-explains/2018/08/01/what-is-shadowbanning> Accessed 15 October 2020.

Smith, Douglass III. “Unlocking Potential: Internet and Prisons”. Benton Foundation, 2016. <https://www.benton.org/blog/unlocking-potential-internet-and-prisons> Accessed 14 October 2020.

Tolentino, Jia. “The Meme Factory.” The New Yorker on the Internet, vol. 95, no. 29, 30 Sept. 2019, p. 34. Gale Academic OneFile,<https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A601918110/AONE?u=amst&sid=AONE&xid=77d915a5> Accessed 10 October 2020.

Weill, Kelly. “Inside the Tumblr Community Where Women Worship Killers”. The Daily Beast on the Internet, 2019. <https://www.thedailybeast.com/inside-the-tumblr-communitywhere-women-worship-killers> Accessed 14 October 2020.

Wells, Georgia. “Facebook Bans Louis Farrakhan, Alex Jones And Others As ‘Dangerous’”. Wall Street Journal on the Internet, 2020. <https://www.wsj.com/articles/facebook-banslouis-farrakhan-alex-jones-and-others-as-dangerous-11556827652?mod=rsswn> Accessed 14 October 2020.