Feminist Movements in the Age of Social Media: Crossing the Thin Line Between Authentic and Performative Activism

By Irem Ergul, Emma Fuchsová, Alexandra Hagedorn

1. Introduction

Activism is conventionally seen as a form of public protest, that is a rally, public meeting or a march (Anderson and Herr 20). In this day and age, however, activism goes far beyond this understanding and is not limited to real-life event participation. The field of digital activism encompasses various forms of collective actions taken by individuals often physically separated by space and time (Grejidanus 2020). There exist a great number of online tools which are being used to engage with this particular form of activism. They include online petitions, social networks, blogs, micro-blogging, mobile phones, proxy servers, and crowdsourcing platforms (Rees, Mitchell 2020). The aforementioned instruments allow for reaching a large number of online participants, simply by defying physical distance and creating an online space for collective actions.

Social media as a particular tool, facilitates the existence of digital activism. Platforms such as Instagram, Facebook or Twitter allow their users to easily disseminate or share information regarding various causes and movements. Despite the guise of simplicity, the reality is more complicated. In recent years, social media activism has turned into a source of innumerable heated debates. Many point out its lack of engagement and genuineness (Aranake 2020). After all, it only takes a few clicks to repost a message or a picture. As a result, many social media users (re)produce a plethora of posts without any commitment to the real issue.

Commenting, sharing, (re)posting, using hashtags and Instagram stories embody the ways in which Instagram can be used as a means of political and civic engagement. Some argue that the main premise of Instagram is to share photos, not information, and this aspect contributes to its performative nature when it comes to activism (Aranake 2020). Such an opinion, however, is not shared by everybody. Many social media activists highlight the importance of visualization. This aspect is crucial in order to make a narrative clear and authentic, which in turn makes it easier for people to get emotionally invested (Ho, McCausland 2020). Instagram stories – which disappear after 24 hours – let their users share various kinds of visual/textual information and educate others. However their fleeting nature contributes to a culture of rapid reposting without substantial content verification. While Instagram offers a virtual space for political and civic engagement, due to its nature it often becomes an arena of self-promotion.

Performative activism, often referred to as ‘slacktivism,’ is a term associated with gaining social capital on various social media platforms in order to be seen in a better light (Meta 2020). It’s a pretense which often has nothing to do with genuine activism. Many people jump on the bandwagon of ‘being woke’ and present a completely altered version of themselves to gain likes. Posting a picture of oneself with a protest sign or using a trending hashtag does not necessarily contribute to spreading any meaningful information, nor does it definitively help the cause. Potentially, these types of posts can redirect attention from the real issue. Unfortunately, there appears to be more and more social media users who contribute to the spread of ‘slacktivism’, ultimately undermining the true intent of digital activism.

2. Context

As the social media platform Instagram has become a place in which political debate can take place, the impact of activist movements has seen an increase. Douglas Kellner (2001) argues that social media enable “new terrains of political struggle for voices and groups excluded from the mainstream media and thus increases potential for intervention by oppositional groups.” (182). However, this does not necessarily suggest that the original or intended message always gets communicated across.

A closer look was taken at two similar movements on Instagram which resulted in a different user interaction and media coverage. In 2019 nearly 500 women were murdered in Turkey by men and numbers have been increasing (Kadin Cinayetlerini Durduracagiz 2019). Apart from that, more than 1000 femicides were registered in Mexico in the year of 2019. Moreover, numbers are expected to increase in 2020 due to the Covid-19 lockdown policies in Turkey and Mexico (The Guardian 2020).

Around July 2020, a Turkish movement emerged on Instagram to address the rising femicide rate and illustrate the violence Turkish women face in their daily lives. With the movement, women wanted to raise awareness for the named issue by applying a black and white filter on their Instagram pictures. This practice was meant to mimic images of Turkish women who were killed featured in Turkish media.

Since Turkish women are seen as responsible for holding up the individual and collective honour, sentences for men are often more mild if they state the women did not behave accordingly (Muftuler-Bac 2-3). Over time, the original message of this Instagram initiative got lost, as many people started posting their black and white pictures without referring to the original message and simply tagged the next person who should take part in this “challenge“. Furthermore, many celebrities who participated were often unaware of the intended message and therefore spread false information (CNN 2020). The movement evolved in the direction of a popularity contest, and over time appeared to be regarded as performative activism, as self-representation came to the fore (Forbes 2020).

Another example that we focused on was a Mexican movement which similarly dealt with femicides. The movement was created by two anonymous Mexican artists after they were faced with an extensive list of femicides in Mexico, which they found shocking (Mardo 2018). This movement was about sharing creatively designed pictures of women who had been murdered or found dead (Gazette 2018). Rather than posting an image of themselves, the participants created portraits of the Mexican women who had lost their lives. The artist duo created an Instagram page titled “No Estamos Todas” (translates to: “We are not all here”) where the artworks could be published (CTV News 2020).

The two movements possess similar backgrounds, however, they have developed differently in their meanings and applications. In the following sections, the focus is on the analysis of the mentioned movements and the means in which they have been applied in different forms and witnessed a change in their meanings.

3. Methodology

For the purpose of examining the posts connected to the Turkish femicide movement on Instagram, we have selected three posts from three different accounts to analyze. To keep the study relevant and feasible, we decided to only pick the Instagram posts of users who had at least 100,000 followers at the time of data collection. The posts belonging to the hashtags #Womensupportingwomen have been accumulated by using the Popsters: Social Media Analytics Tool. The dates have been filtered from July 21st to August 21st; the former being the date on which Pinar Gultekin, a Turkish woman, was declared murdered by her ex boyfriend. This tragic incident was the leading event that contributed to the rise of the movement in Turkey. Moreover, a spreadsheet has been accumulated with the results and with the help of a random number generator, three accounts have been selected that fit the aforementioned criteria. Though selecting from a bigger variety of accounts, such as accounts that had a smaller number of following would have yielded a more fair research, due to the capacity and time limitation of this project we opted for a more feasible path.

In order to examine the posts made for the Mexican femicide movement, we focused on one account in particular, as this was the account in which the artwork was posted, @noestamostodas. It should also be noted that the account tagged the authors of the featured artworks. In order to keep the study fair, we used Popsters: Social Media Analytics Tool. Furthermore we used an Excel spreadsheet and a random number generator to pick three random posts from the @noestamostodas Instagram account.

The research has been completed by conducting both a visual and textual analysis of the selected Instagram posts. The visual content was examined by inspecting the uploaded image, what the image involves and what it is depicting. The textual analysis included the observation of the caption and the comments made under the post.

3.1 Visual and contextual analysis of the Instagram posts

The analysis of the six individual posts has yielded for many interesting results, those which have led us to question the reasons behind the success of a certain feminist movement in comparison to another.

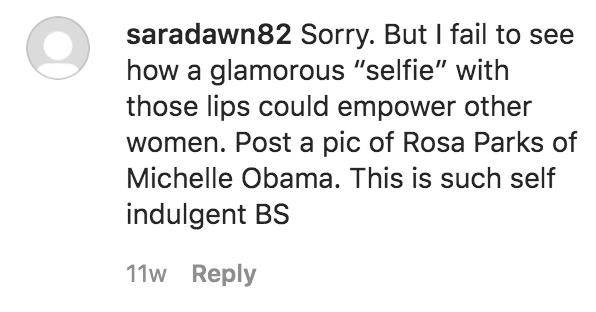

Figure 1 below illustrates the image posted by Lisa Rinna, an American reality television star with the hashtag “#Womensupportingwomen”. Additionally, Figures 2 and 3 portray some examples of the comments the actress has received.

The photograph depicts Linna in a revealing lace dress, posing for the camera while puckering her lips. As made apparent from the screenshots above, the actress has received a mix of negative and positive comments. Whilst some of her followers admired her for her strength and labeled her as a “legend”, some made a point in questioning “how a glamorous ‘selfie’ … could empower women”. Furthermore some questions regarding her awareness of the purpose of the movement have been raised. Although in her caption she talks about women empowerment and its importance, no mention of the true origin of the movement is to be seen.

Figures 4, 5 and 6 below exemplify the post created by an American celebrity Paris Hilton and the comments she has received.

The caption of Hilton’s picture discusses the importance of womanhood and women supporting each other. Scrolling through the comments under this post, what stands out is the number of heart emojis, admiring words and praise the star has received. From over a thousand comments, only a few suggest what the hashtag and the movement derived from.

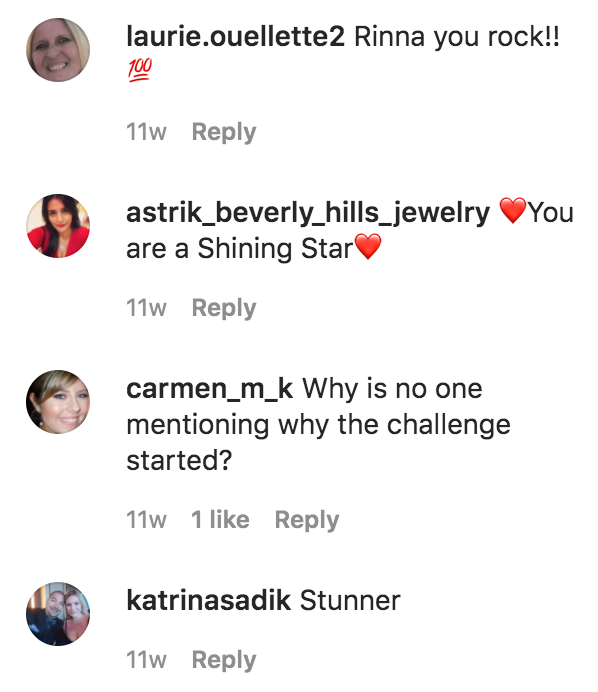

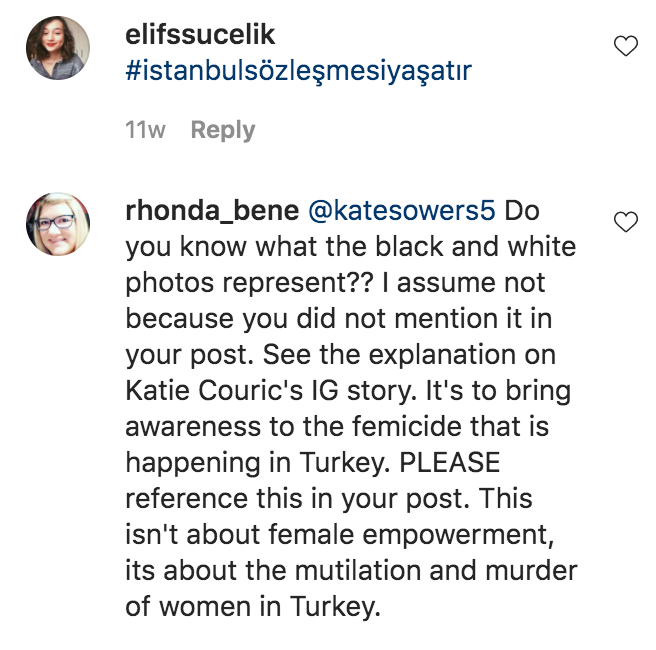

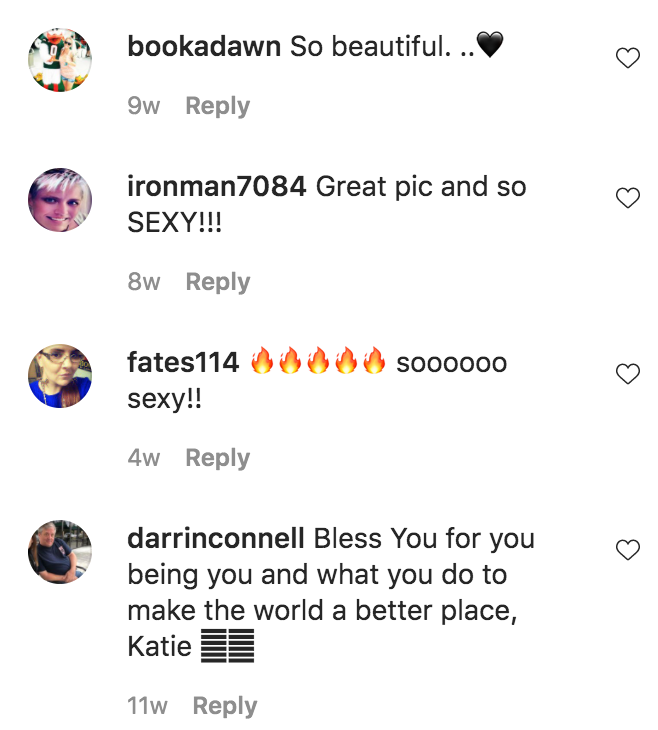

The last analyzed post is one that belongs to Katie Sowers, an American football assistant coach. Figures 7, 8 and 9 below illustrate the image posted by Sowers and the comments she has received.

Whilst Rinna and Hilton decided to use the space given to reflect back on womanhood and sisterhood, Sowers has accompanied her image with a simple “Challenge accepted” and two hashtags. In the course of the analysis, it became apparent there was a relative balance between the amount of comments that seemed to praise her and the ones which were referring back to the purpose of the movement. Another interesting aspect of the comment section was the fact that there was an immense number of comments regarding her beauty and looks. This is almost contradictory to what the commencement of the movement was about, which was to focus on womanhood and saving women’s lives.

In the following section, three Instagram posts created in support of the Mexican femicide movement have been analysed. It should be noted that in contrast with the #WomenSupportingWomen challenge, the Mexican femicide tag has been mostly manifested through the chosen Instagram page. This aspect has had a direct effect on the number of likes and comments under each of the analysed posts.

In Figure 10 above, the artwork created by Zermeno depicts a murdered Mexican woman called Lizet. The caption features the date of the murder, the name of the woman, her age, city of origin and by whom the illustration was created. Furthermore, seven different hashtags have been added to the caption, referring to the movement and Mexican femicides. The first sentence of the caption reads “No estamos todas, nos falta…”, which translates to “We are not all here, we are missing (name of woman)”. There is only one comment posted under the image, and that is an emoji with heart eyes. Furthermore, Figure 11 below showcases an artwork created by an artist Laura de Leon.

The image showcases an artwork created by Zermeno, depicting Tenia, another murdered woman from Mexico. The caption of the image is almost identical to the aforementioned one. It states the date of the murder, age and the city of origin. The same hashtags were used, and the author of the image was tagged. The only comment made on the image is made by the same user as the one before, featuring an emoji with heart eyes. Interestingly, a white flower was drawn concealing the woman’s face. In art and literature, the motif of a flower has widely been used to represent beauty, femininity and innocence (Stott 68). The white flower depicted in the artwork above may thus have been used as a metaphor for fragility and pure femininity. Additionally, the particular placement of the flower may also depict the ever-growing number of femicides in Mexico, and how they each slowly turn from an individual case to merely a statistic. Finally, the image below illustrates the last post that was analysed regarding the Mexican femicide movement.

Figures 10 and 11 above illustrate the artwork created by Mayra Canela. Translated from Spanish, the description of the woman reads, “Jovita’s friends describe her as a hard-working, cheerful, sincere young woman who was always committed to whatever work she did”. Though it cannot be stated that there is a direct correlation between the caption and comments, this post in particular has received more comments than the ones mentioned before. The comments include emojis of despair, praise and “Por jovita!”, which translates to “For Jovita!”, Jovita being the woman in the image. Additionally, similarly to the previous post, floral motifs have been included in the artwork, where they appear to be blooming from the bottom of the picture. Pink tones also stand out in the image, a color that has been vastly correlated with femininity and delicacy in literature and popular culture (Harris 119). As made apparent in the posts examined in this section, the means in which each user has taken part of the movements differs heavily.

4. Discussion and conclusion

Although, both of the analysed movements started with a similar intention, they took a different course over time. The Turkish movement lost its original meaning and its importance shifted from a femicide movement to an empowering women tag challenge. The focus shifted to self-promotion, rather than spreading awareness regarding the cause. This deceptive understanding was further reinforced by the participation of celebrities, many of which have been supported by their fans and followers. The misunderstanding resulted into a form of performative activism. By posting black and white pictures of themselves, accompanied by the hashtag #WomenSupportingWomen, the participants did not spread any awareness nor they referred to the original purpose of the Turkish femicide movement. It remains unclear whether the majority of them were aware of the origin of this movement, as this was not made apparent in the posts itself.

The Mexican Movement stayed relatively small, however, it remained true to its original meaning. The re-creation of the images of the deceased women carried the intention of the movement with a deeper understanding. Therefore, the participation in this movement required more effort and time than the former. This may have been the reason for this movement not gaining the same coverage but keeping its intended meaning, since only people who really cared about the background actually made the effort to participate in it. This can be attributed to the fact that the Turkish movement was similar to a quick tag challenge and the Mexican was a more creative initiation. The Turkish movement required far less effort and creativity and was therefore distributed more quickly.

Waves of social media trends appear on a daily basis, and at times it is hard to depict what they mean or where they originated from. Seeing examples of performative activism on Instagram may be frustrating at times, especially when we are surrounded by individuals who pride themselves in their authenticity (Chae 259). The research conducted has brought up several points of discussion, particularly whether self-empowering selfies constitute performative activism. Women, especially those in power, can accomplish a great deal for gender equality. It is without a doubt that we are so fortunate as to have political debates, exchange viewpoints and connect with our loved ones through social media. Unfortunately, because of the decentralized structure of social media platforms, such as Instagram, it may be rather difficult to keep track of the sources of each ‘trend’. Turkey and Mexico, in comparison with the United States, are countries in which free speech is comparatively limited and social media challenges and hashtags may act as a space for raising awareness and starting a conversation.

5. References:

“2019 November Report of We Will End Femicide Platform”, Kadin Cinayetlerini Durduracagiz,

http://kadincinayetlerinidurduracagiz.net/veriler/2890/2019-report-of-we-will-end-femicide-platform. Accessed 19. Oct. 2020

“Activism, Social and Political.” Encyclopedia of Activism and Social Justice, by Gary L. Anderson and Kathryn G. Herr, Sage, 2007, p. 20.

Aranake, Shreeya. “Take Your Activism Away from Instagram.” The GW Hatchet, 17 June 2020, www.gwhatchet.com/2020/06/16/take-your-activism-away-from-instagram/. Accessed 20 Oct. 2020.

“Challenge Accepted: Turkish Feminists Spell out Real Meaning of Hashtag.” The Guardian, 31 July 2020, http://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/jul/31/challenge-accepted-turkish-feminists-spell-out-real-meaning-of-hashtag. Accessed 19. Oct. 2020

Chae, Jiyoung. “Explaining Females’ Envy Toward Social Media Influencers.” Media Psychology, vol. 21, no. 2, Routledge, Apr. 2018, pp. 246–62. Taylor and Francis+NEJM, doi:10.1080/15213269.2017.1328312.

“‘Empowerment’ Selfies Are Burying a Turkish Women’s Rights Campaign.” KQED, https://www.kqed.org/arts/13883979/empowerment-selfies-are-burying-a-turkish-womens-rights-campaign. Accessed 20 Oct. 2020.

Andrew, Scottie. “No, the Instagram ‘challenge accepted’ trend did not originate in Turkey”, CNN,https://edition.cnn.com/2020/07/30/us/challenge-accepted-turkey-instagram-trnd/index.html. Accessed 19 Oct. 2020.

Greijdanus, Hedy, et al. “The Psychology of Online Activism and Social Movements: Relations between Online and Offline Collective Action.” Current Opinion in Psychology, vol. 35, 2020, pp. 49–54., doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2020.03.003.

Harris, Anita. All About the Girl: Culture, Power, and Identity. Routledge, 2004.

Ho, Shannon, and Phil McCausland. “How Instagram Became a Destination for the Protest Movement.” NBCNews.com, NBCUniversal News Group, 29 June 2020, www.nbcnews.com/tech/tech-news/how-instagram-became-destination-protest-movement-n1232342.

Katie Sowers on Instagram: “Challenge Accepted #womenempowerment #womensupportingwomen . . . . . @coach_lo_loc #49ers #niners #faithful #ninerfaithful #ninergang….” https://www.instagram.com/p/CDKj_cZhOzk/. Accessed 18 Oct. 2020.

Kellner, Douglas. “Globalisation, Technopolitics and Revolution.” Theoria: A Journal of Social and Political Theory, no. 98, Berghahn Books, 2001, pp. 14–34.

L I S A R I N N A on Instagram: “I Am so Moved by This Challenge I’ve Had so Many Amazing Women in My Life That I Adore! Thank You to Them All! Challenge Accepted Again! 🤍….” https://www.instagram.com/p/CDJsfCYjOiS/. Accessed 18 Oct. 2020.

Mardo, Paola. “An Instagram art project spreads awareness about femicides in Mexico.” Post Gazette, https://www.post-gazette.com/news/world/2018/03/05/An-Instagram-art-project-spreads-awareness-about-femicides-in-Mexico/stories/201803010256. Accessed 19 Oct. 2020.

Mardo, Paola. “Instagram Art Project Spreads Awareness about Femicides in Mexico.” The World from PRX, https://www.pri.org/stories/2018-03-02/instagram-art-project-spreads-awareness-about-femicides-mexico. Accessed 18 Oct. 2020.

Metta, John. “The Problem of Performative Activism.” US & Canada | Al Jazeera, Al Jazeera, 20 July 2020, www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2020/7/20/the-problem-of-performative-activism/. Accessed 20 Oct. 2020.

Muftuler-Bac, Meltem, and Canan Muftuler. “Provocation Defence for Femicide in Turkey: The Interplay of Legal Argumentation and Societal Norms.” European Journal of Women’s Studies, May 2020, doi:10.1177/1350506820916772.

No Estamos Todas on Instagram: “No Estamos Todas, Nos Falta… 11/01/17 – Jalisco – Tenia Aproximadamente 25 Años Ilustración Por: Laura de León IG: @nklauradleon.” https://www.instagram.com/p/Bb5pIHUgpba/?utm_source=ig_embed. Accessed 18 Oct. 2020.

No Estamos Todas on Instagram: “No Estamos Todas, Nos Falta Jovita Amistades de Jovita La Describen Como Una Joven Trabajadora, Alegre, Sincera y Siempre Comprometida Con….” https://www.instagram.com/p/B9LLI3cDXPv/. Accessed 18 Oct. 2020.

No Estamos Todas on Instagram: “No Estamos Todas, Nos Falta Lizeth 16/04/17 – Puebla – Tenía 32 Años Ilustración Por: Melissa Zermeño IG: @mel.Zermeno.” https://www.instagram.com/p/Bd0vdTDA9ve/?utm_source=ig_embed. Accessed 18 Oct. 2020.

Paris Hilton on Instagram: “#ChallengeAccepted 🥰 Thank You to All the Amazing Women for Your Beautiful Messages & Nominating Me for This Challenge. I Love You All! I….” https://www.instagram.com/p/CDK_DJAp-T0/?utm_source=ig_embed. Accessed 18 Oct. 2020.

Popsters – Social Media Content Analytics Tool. https://popsters.com/. Accessed 18 Oct. 2020.

Rees, Anna, and Kristine Mitchell. “Digital and Online Activism: Responsibility.” RESET.to, https://en.reset.org/knowledge/digital-and-online-activism. Accessed 20 Oct. 2020.

Somos, Christy. “Outraged Mexicans flood social media with beautiful images to drown out photos of murdered woman.” CTV NEWS,

https://www.ctvnews.ca/world/outraged-mexicans-flood-social-media-with-beautiful-images-to-drown-out-photos-of-murdered-woman-1.4810414. Accessed 20 Oct. 2020.

Sternlicht, Alexandra. “#ChallengeAccepted: Here’s Why Women Are Posting Black And White Photos On Instagram”, Forbes,https://www.forbes.com/sites/alexandrasternlicht/2020/07/28/challengeaccepted-heres-why-women-are-posting-black-and-white-photos-on-instagram/#221f92371379. Accessed 20 Oct. 2020.

Stott, Annette. “Floral Femininity: A Pictorial Definition.” American Art, vol. 6, no. 2, [University of Chicago Press, Smithsonian American Art Museum], 1992, pp. 61–77.