The future in the eye of the beholder?: Facebook’s Ray-Ban Stories and their claim on our data

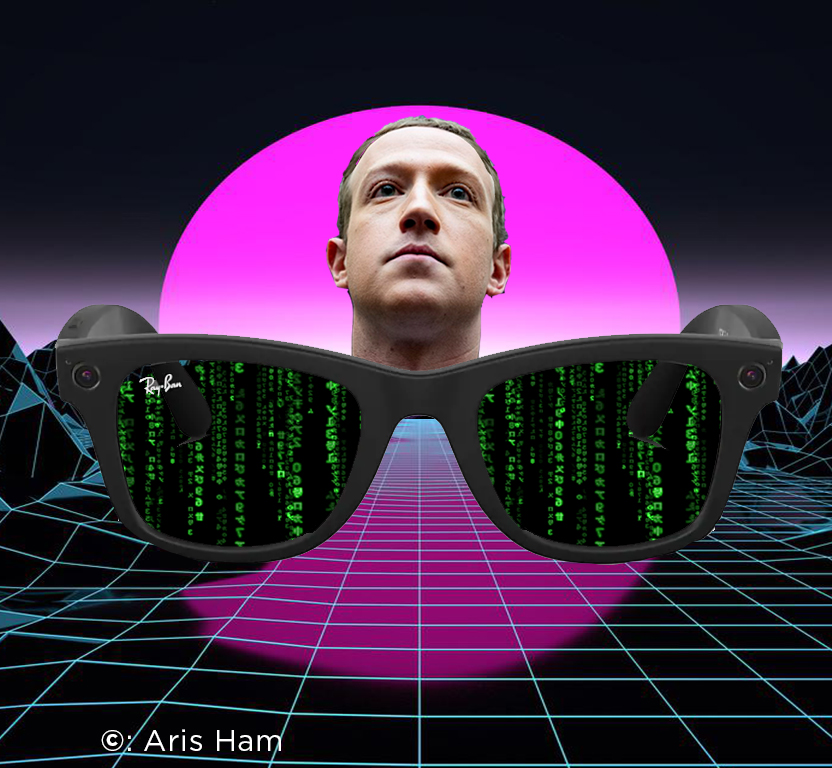

Since Baudrillard made his famous notion about a ‘hyperreality’ in his book ‘Simulacra and Simulation’ (1981), many people have been inspired by his differentiating views on reality. Big Tech companies are since their foundations influenced by the concept of creating a ‘hyperreality’ or in Mark Zuckerberg’s (CEO of Facebook) words a ‘metaverse’ (Casey, 2021), which could be explained as ‘a virtual world that connects virtual worlds with each other and with the real reality (NRC, 2021). Technology companies have for a long time been obsessed with trying to seize humanity’s senses through their products and services to monetize our data and execute their utopian visions about the future of technology. The newest invention in this range of technology is the ‘Ray-Ban Stories’ (Facebook, 2021): a pair of glasses made by Facebook’s development team with the goal to combine the functionalities of your phone with the optical spectacles that many people see their world through daily. Hereby, extending our bodies with technology and moving closer to the concept of a Cyborg (Donna Haraway, 2006), in which we break down the boundaries between humans and machines.

The idea of e-glasses is not new: companies like Google and Snapchat have developed their versions of the e-glasses in the last few years, but they had not much success due to their ugly designs, bad-marketing strategies and timing (Wired, 2018). Facebook tries to do it slightly differently this time by doing a stylish collaboration with one of the world’s most popular sunglasses brands and by developing a more subtle product design. Mark Zuckerberg said that his plan in creating the glasses is to ‘ultimately replace mobile phones with Facebook Smart Glasses’ (technologyreview, 2021).

Critical Questions

With these innovations, the following questions arise: how much privacy are we willing to give up for the creation of an environment in which the rules are determined by the same people that control the means of production within a framework of communicative capitalism (J. Dean, 2015, as cited in Hillis, Paasonen, Petit, 2015)? And what are the implications for our privacy with Big Tech companies seizing our eyes for monetization?

To answer the questions imposed above I will use the article ‘Critical Questions for Big Data’ by Boyd & Crawford (2012) to substantiate my argumentation. When examining the ‘Ray-Ban stories’, we must evaluate the technology in the interactions with the ‘social ecology’ in which it functions. ‘Technological developments frequently have ‘environmental, social, and human consequences that go far beyond the immediate purposes of the technical devices and practices themselves’ (Kranzberg 1986, p. 545, as cited in Boyd and Crawford, 2012). With this article and the subject of privacy as a framework, I take a critical perspective on the way e-glasses could change our environment.

Ray-Ban Stories

Boyd & Crawford (2012) state that ‘Big Data is seen as a troubling manifestation of Big Brother, enabling invasions of privacy, decreased civil freedoms, and increased state and corporate control’ (664). The most striking example of this concerning privacy issues is that the glasses possess two little camera’s on the top of the screen that could film their surroundings. Ideal when you are walking your pet and want to take some cute snapshots of them, but they could also be used for other – less normative – purposes, such as ‘card-skimming’, fraud or filming and leaking certain business data. Purposes that Facebook has no real solution for in mind yet other than a suggestion for the ‘best practices in which they include ‘not to use the device in private spaces’, and advising users not to ‘engage in harmful activities’ (theconversation, 2021). To assume that everyone will comply with these rules is very naïve.

Furthermore, Boyd & Crawford illustrated that ‘Just because it (i.e. data) is accessible does not make it ethical’ (671, 672) regarding the available data that is up for grabs on social media. With the e-glasses, the grey area that existed between what is private and what is public when filming with your smartphone vanishes even more with glasses that will allow you to stealthy record everything and everyone that you cross. Often without people noticing. While twenty years ago, the only way of filming people in the streets was through pointing large camera lenses at them. With the rise of smartphones, the sentiment has changed our perspective on these privacy issues and recording people became easily possible without them even noticing they are being subject to it. According to a spokesman for a privacy forum non-profit (funded by Facebook), the reason for this semi-public acceptance is that ‘the public’s expectations of privacy have changed since the days of previous smart glasses releases’ (NYTimes, 2021). But is this an effect that humans have imposed on themselves all along? Or is it slowly implemented through new updates and applications with long, vague contracts imposed by Big Tech companies? Whenever I ask people around me if they would want improvements for their online privacy, they answer that they value it and rather would want to have more ownership over it, but that the functionalities of the products and services made by these companies are just too crucial to our modern way of living. Examples of this are the use of work-related group chats in Whatsapp, in which important notifications are mentioned or the reliance on the Google search function to perform effective and efficient search results when you need to find anything specific.

Accountability

With Facebook trying to colonize even more parts of our bodies for data monetization, the important question to ask is; to which extent could we trust the accountability of powerful social media companies like Facebook in protecting important civic matters such as privacy? Concerning working with data, Boyd & Crawford (673) plead for steering the focus away from privacy awareness only and moving to the ‘accountability’ that researchers have in working with data. It also applies to the way companies like Facebook should take their responsibility. The company could be more concerned with its users and protect their ‘rights and well-being’ (673) by developing products that handle issues such as privacy and data with more care. The Ray-Ban glasses are an example that they do not have held those values high in the last few years and are probably not about to change their ways in the neoliberal structure that we have created for them in which they thrive.

Bibliography

- Applin, Sally. 2021. ‘Why Facebook Is Using Ray-Ban to Stake a Claim on Our Faces’. MIT Technology Review. Accessed 21 September 2021. https://www.technologyreview.com/2021/09/15/1035785/why-facebook-ray-ban-stories-metaverse/.

- Boyd, Danah, and Kate Crawford. 2012. ‘CRITICAL QUESTIONS FOR BIG DATA: Provocations for a Cultural, Technological, and Scholarly Phenomenon’. Information, Communication & Society 15 (5): 662–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2012.678878.

- Egliston, Ben, and Marcus Carter. 2021. ‘Ray-Ban Stories Let You Wear Facebook on Your Face. But Why Would You Want To?’ The Conversation. Accessed 29 September 2021. http://theconversation.com/ray-ban-stories-let-you-wear-facebook-on-your-face-but-why-would-you-want-to-167708.

- Eveleth, Rose. 2018. ‘Google Glass Wasn’t a Failure. It Raised Crucial Concerns’. Wired. Accessed 27 September 2021. https://www.wired.com/story/google-glass-reasonable-expectation-of-privacy/.

- Haraway, Donna. 1994. Een cyborg manifest. Amsterdam: De Balie.

- Hillis, Ken, Susanna Paasonen, and Michael Petit, eds. 2015. Networked Affect. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press: 1-24

- ‘Introducing Ray-Ban Stories: First-Generation Smart Glasses’. 2021. About Facebook. 9 September 2021. Accessed 29 September 2021. https://about.fb.com/news/2021/09/introducing-ray-ban-stories-smart-glasses/.

- Isaac, Mike. 2021. ‘Smart Glasses Made Google Look Dumb. Now Facebook Is Giving Them a Try.’ The New York Times, 9 September 2021, sec. Technology. Accessed 29 September 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/09/09/technology/facebook-wayfarer-stories-smart-glasses.html.

- Kist, Reinier. 2021. ‘Silicon Valley is in de ban van een nieuwe visie op de digitale toekomst: de metaverse. Wat is dat?’ NRC. Accessed 29 September 2021. https://www.nrc.nl/nieuws/2021/09/13/is-het-eind-van-het-scherm-tijdperk-nabij-a4058144.

- Newton, Casey. 2021. ‘Interview: Mark Zuckerberg on Facebook’s Metaverse’. The VergeCast. Accessed 1 October 2021. https://open.spotify.com/episode/0ouoP9Qb96XMgfT5kt5ZEk. 1:10 – 19:10.