Cut the Cookie: Dark Patterns in BIG DATA

Cookies, introduced as a promise of choice, developed into an institutional nuisance one encounters daily. Formerly an attempt to provide Europeans with a consent infrastructure for or against participation in Big Data practices turned into an exercise in ethical ambiguity through the platform economy and misleading interface design.

CREDIT: COURTESY OF SESAME WORKSHOP / SESAME STREET (edited by Author)

Introduction

Humans have asked for millennia, if and how they will be remembered, what will be left?[1] Data: If the Information age has provided one answer to the existential dread, it might be that one will not be forgotten, not by the algorithmic machines.[2] Nevertheless, before there may be immortal data or digital traces, a medium is required to capture the shape of the footprints. Are the tools for collection and preservation genuine? What If one does not want to be remembered? Not for one’s digital traces nor imaginary selves, since “just because data is accessible does not make it ethical.”[3] The following commentary examines the rift between creators and collectors of data, asking if cookies and dark patterns constitute an ethical device for traditional informed consent by online users.

Platform Economy

Data being the most valuable commodity of the 21st century, large infrastructural platforms such as Facebook and Google are spearheading how the valuable resource is extracted and refined.[4] Platforms employ tracking cookies, small blocks of data which are saved to the users’ computer through the web browser, including bits of information about the users long-term browsing history – for readying external data for their databases, promising clients using Big Data tools such as google analytics better insights into their user base.[5]

Establishing Oversight

Boyd and Crawford interrogate the big data paradigm in their article “Critical Questions for Big Data” and describe the imbalance in power dynamics of digital actors as a standoff between the Data-Rich versus the Data poor, attributing the digital divide embraced through the platform economy due to the “deep government and industrial drive towards gathering maximal value from data…leading to more targeted advertising, product design, traffic planning, or criminal policing.“[6] Furthermore, pointing to the ethical dilemma, the Data-Rich would face when capturing and keeping data on a consensual basis and if such practices are designed to constitute forms of traditional informed consent by the Data Poor.[7]

As a detriment to the wide-ranging implications of consensual data practices, the European Union adopted the ePrivacy Directive the EU Cookie Law in 2002.[8] Stating that “data must be processed fairly for specified purposes and based on the consent of the person concerned” and further “no cookies and trackers must be placed before prior consent from the user, besides those strictly necessary for the basic function of a website.”[9] Drafting the General Data Protection Regulation, The European Union expanded on the Directive to regulate Big Data practices of the Data-Rich. The legal framework is an attempt to (re-)instates data sovereignty of EU Citizens and Residents, “designed to give individuals more control over how their data is collected, used and protected online.”[10] Under the GDPR, Websites targeting European Union member states must gain informed consent from users before storing non-essential cookies on their device. The GDPR identifies two classes of the Data-Rich – Data Controllers and Data Processors.[11] Following the ePrivacy Directive and Article 25, Data Controllers and Producers are obligated to implement “Data protection by design and by default,” providing “natural persons” access to choose if they want to opt-in or opt-out of tracking, thus being part of Big Data practices by giving consent and be remembered following Article 17, or the right to be forgotten.[12] [13]

Succeeding the introduction of the ePrivacy Directive and GDPR, internet users across Europe, upon visiting a website, are greeted with large banners asking for consent to save Cookies for tracking purposes. Despite the immediate presence of the European consent architecture informing of a digital interface, large proportions of web users remain unclear on how to engage with the consent mechanism.[14] The confusion among users may be by design – as nudging techniques such as Dark Patterns can be observed throughout web applications. [15]

Techniques of Opaqueness

While small-scale businesses struggle with the successful implementation and compliance of the GDPR, the Data-Rich utilize strategies of opaqueness such as Dark Patterns. Dark Patterns describe features of interface design crafted to trick users into doing things they might not want to do, but which benefit the business in question.[17] [18]

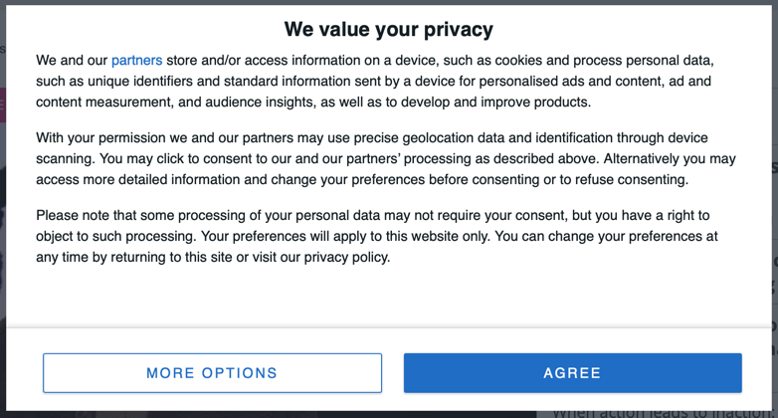

An example of a Dark Pattern is how informed consent is translated into the interfaces of tracking cookies. The button for agreeing to be tracked is distinguished by using a contrasting color while displaying a less visible smaller link to “more options” – more options leads the user to a more complicated menu were opting out – could be achieved – fostering an imbalance to ease of access to data sovereignty of the individual. (Figure 1.)[19] Users determined to op-out are confronted with a list of tracking cookies, which must be checked before scrolling to the bottom of the page to save the settings, which accounts for the users’ consent decision. Therefore, the interface discourages the users’ desire not to be tracked – opting out, demanding to engage with a time-consuming and confusing process of opting out or accepting being tracked.[20]

Conclusion

If the User is neither capable of evaluating the interface’s affordance nor interacting, not being equipped with cultural or institutional knowledge – an organization dedicated to capturing and keeping data is at an advantage. Moreover, considering the confusion experienced by large proportions of Internet users when encountering cookie banners, the widespread press coverage of the GDPR in its quest for curbing data hegemonies of the “Data-Rich” did not lead to an inclusive reality of digital informed consent. The affordance provided by the governance regime of the Data-Rich produces normative structures in user behavior of the Data Poor by discouraging practices of informed consent through employing opaque techniques of Dark Patterns in cookie banners.[21] Besides expressing ethical ambiguity, it remains in question if the techniques employed breach Article 25 of the GDPR, hindering users from exercising their right to consent as stated in the ePrivacy Directive and being forgotten, as stated in Article 17. Consequently, hardening the class-based structure due to inequalities, designed as part of the system by the Data-Rich.[22] Thus, further dividing those who have the means of collection and analysis and those who do not want to be remembered.

Bibliography

General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). “Art. 17 GDPR – Right to Erasure (‘Right to Be Forgotten’).” Accessed October 3, 2021. https://gdpr-info.eu/art-17-gdpr/.

General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). “Art. 25 GDPR – Data Protection by Design and by Default.” Accessed October 3, 2021. https://gdpr-info.eu/art-25-gdpr/.

Boyd, Danah, and Kate Crawford. “CRITICAL QUESTIONS FOR BIG DATA: Provocations for a Cultural, Technological, and Scholarly Phenomenon.” Information, Communication & Society 15, no. 5 (June 2012): 662–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2012.678878.

Campbell-Dollaghan, Kelsey, and Kelsey Campbell-Dollaghan. “The Year Dark Patterns Won.” Fast Company, December 21, 2016. https://www.fastcompany.com/3066586/the-year-dark-patterns-won.

GDPR.eu. “Cookies, the GDPR, and the EPrivacy Directive,” May 9, 2019. https://gdpr.eu/cookies/.

“Dark Patterns.” Accessed October 3, 2021. https://www.darkpatterns.org/.

“Dark Patterns Are Designed to Trick You (and They’re All over the Web) | Ars Technica.” Accessed October 3, 2021. https://arstechnica.com/information-technology/2016/07/dark-patterns-are-designed-to-trick-you-and-theyre-all-over-the-web/.

Davis, Jenny L., and James B. Chouinard. “Theorizing Affordances: From Request to Refuse.” Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society 36, no. 4 (December 2016): 241–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/0270467617714944.

Esposito, Elena. “Algorithmic Memory and the Right to Be Forgotten on the Web.” Big Data & Society 4, no. 1 (June 1, 2017): 2053951717703996. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951717703996.

“EUR-Lex – 32002L0058 – EN – EUR-Lex.” Accessed October 3, 2021. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX%3A32002L0058.

Helmond, Anne. “The Platformization of the Web: Making Web Data Platform Ready.” Social Media + Society1, no. 2 (July 1, 2015): 205630511560308. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305115603080.

TechRadar. “TechRadar | The Source for Tech Buying Advice.” Accessed October 3, 2021. https://www.techradar.com/uk.

“The World’s Most Valuable Resource Is No Longer Oil, but Data.” The Economist, May 6, 2017. https://www.economist.com/leaders/2017/05/06/the-worlds-most-valuable-resource-is-no-longer-oil-but-data.

Utz, Christine, Martin Degeling, Sascha Fahl, Florian Schaub, and Thorsten Holz. “(Un)Informed Consent: Studying GDPR Consent Notices in the Field.” In Proceedings of the 2019 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, 973–90. London United Kingdom: ACM, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1145/3319535.3354212.

European Commission – European Commission. “What Is a Data Controller or a Data Processor?” Text. Accessed October 3, 2021. https://ec.europa.eu/info/law/law-topic/data-protection/reform/rules-business-and-organisations/obligations/controller-processor/what-data-controller-or-data-processor_en.

GDPR.eu. “What Is GDPR, the EU’s New Data Protection Law?,” November 7, 2018. https://gdpr.eu/what-is-gdpr/.

“Who Will Be Remembered in 1,000 Years? – BBC Future.” Accessed October 3, 2021. https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20171220-how-to-be-remembered-in-1000-years.

[1] “Who Will Be Remembered in 1,000 Years? – BBC Future.”

[2] Esposito, “Algorithmic Memory and the Right to Be Forgotten on the Web.”

[3] Boyd and Crawford, “CRITICAL QUESTIONS FOR BIG DATA.” Page. 671

[4] “The World’s Most Valuable Resource Is No Longer Oil, but Data.”

[5] Helmond, “The Platformization of the Web.”

[6] Boyd and Crawford, “CRITICAL QUESTIONS FOR BIG DATA.” Page. 675

[7] Boyd and Crawford. „CRITICAL QUESTIONS FOR BIG DATA.”

[8] “EUR-Lex – 32002L0058 – EN – EUR-Lex.”

[9] “Cookies, the GDPR, and the EPrivacy Directive.”

[10] “What Is GDPR, the EU’s New Data Protection Law?”

[11] “What Is a Data Controller or a Data Processor?”

[12] “Art. 25 GDPR – Data Protection by Design and by Default.”

[13] “Art. 17 GDPR – Right to Erasure (‘Right to Be Forgotten’).”

[14] Utz et al., “(Un)Informed Consent.”

[15] Campbell-Dollaghan and Campbell-Dollaghan, “The Year Dark Patterns Won.”

[16] “TechRadar | The Source for Tech Buying Advice.” Screenshot

[17] “Dark Patterns.” darkpatterns.org

[18] “Dark Patterns Are Designed to Trick You (and They’re All over the Web) | Ars Technica.”

[19] “TechRadar | The Source for Tech Buying Advice.” Screenshot

[20] Davis and Chouinard, “Theorizing Affordances.”

[21] Davis and Chouinard.

[22] Boyd and Crawford, “CRITICAL QUESTIONS FOR BIG DATA.”