Feminist Tools for Feminist Research

In the margins stand other softwares, approaches, and visions to resist mainstream and extractivist technologies that stand in the back-end of even the most feminist methods. Adopting these tools is itself an act of resistance. In the hegemony stand the megalomaniac server centres, extracting data and natural resources. How can we imagine servers and data practices that resist, that exist in the margin?

In Margins as Methods, Margins as Ethics: A Feminist Framework for Studying Online Alterity, Rosemary Clark-Parsons and Jessa Lingel outline practices and methods when studying “marginalised or activist media” (2020). Unbalanced power relations and lack of inclusive tools still pertain to most of Academia, turning the research of these groups often one-sided, while risking “oversimplifying contexts” and “romanticise resistance” (Abu-Lughod 1990 in Clark-Parsons and Lingel 2020). In an insightful yet pragmatic approach, the authors identify challenging aspects of digital methods research such as “engaging with personal data in a manner that does not further disempower groups”, and conclude with “guiding questions” and suggested approaches that might help bridge gaps and contribute to a more inclusive and diverse research practice. These methods mainly centre around notions of “situated knowledge” (Haraway 1988 in Clark-Parsons and Lingel 2020) and “feminist ethics of care”, bringing feminist reflexivity to digital methods and highlighting each and every step of the research process.

This is an important and powerful gesture towards acknowledging marginal, more radical ways of thinking academic research, particularly key if we are to move towards including all identities and ways of living online and beyond. But not only the methods, but the tools matter. One aspect that was left out in this article was the kind of digital tools we use and thrive for towards inclusive, feminist data research. In the margins stand other softwares, approaches, and visions to resist mainstream and extractivist technologies that stand in the back-end of even the most feminist methods. Adopting these tools is itself an act of resistance, “the possibility of radical perspective from which to see and create, to imagine new alternatives, new worlds” (hooks 1989).

In the hegemony stand the megalomaniac server centres, extracting data and natural resources. How can we imagine servers and data practices that resist, and exist in the margin?

Feminist approaches to technology aren’t new, and neither are marginal imaginaries of online futures. While this essay doesn’t aim to draw a (her)storical perspective on cyberfeminism, it is important to acknowledge the past efforts and situatedness from which the following examples and arguments come. In her famous chapter-manifesto, Haraway lays out the liberating possibilities for a cyborg existence and writing, as a gesture towards “seizing the tools to mark the world that marked them as other” (1991). Imagining digital futures as cyborg, Haraway describes them as “imagination[s] of a feminist speaking in tongues”, that “both build and destroy machines, identities, categories, relationships, space stories.” This work revolutionises not only writing in itself but the way cyberspace had been conceptualised until then, mostly by Silicon Valley white, male figures (Ensmenger 2015).

This essay centres — or brings to the margin — A Feminist Server Manifesto (2013), a text written collectively that outlines and imagines what could a feminist server mean. It followed discussions during the workshop Are you Being Served?, questioning similar aspects as outlined by Haraway, in the “phallogocentrism” of the “one code that translates all meaning perfectly” (1991) and other marginal approaches to data and the internet. In this context, one can point out that the manifesto as a cultural object, more particularly within technological culture, is “a tool for establishing new epistemological ground towards world-making” (Foster 2020) and creating new worlds and collective visions, situating this object as key to feminist movements in the past and present times.

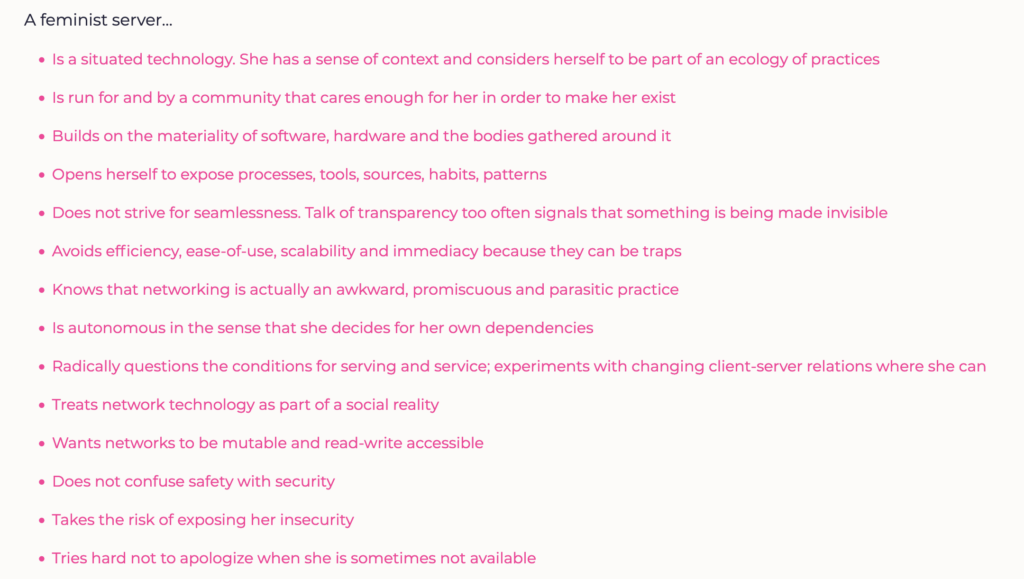

A Feminist Server Manifesto is a short series of one-line sentences that describe this imaginary-possible object:

Even though this manifesto might not translate or encompass all feminist translations of technology and data, it was conceptualised with an ecological (“network technology as part of social reality”), feminist ethics of care (“run for and by a community that cares”) and marginal (“does not strive for seamlessness”) mindset, translating what Clark-Parsons and Lingel refer to as “alternative media” produced by a “counterculture” (2020). In fact, the workshop that produced this manifesto was hosted by Constant, an artist-run space dedicated to art, media, and technology. Small cultural organisations such as these are worth researching, as they not only produce cultural value in the fields of new media, — independently from any mainstream platforms — but also develop alternative tools and softwares within the copyleft and open-source software movements.

Also worth noting is that this manifesto encompasses both Clark-Parsons and Lingel’s definition of the “counterculture” and “counter publics” (2020), by intersecting marginal digital practices and marginalised bodies, namely women or feminist identifying people. Open source movements are often populated by male voices, which is why it remains important that feminist thinking takes part in shaping marginal digital practices. In an interview for Haus der Elektronischen Künste Basel, Femke Snelling underlines the importance of practising and researching feminist technology, by developing new methods, imagining new futures, and understanding what “feminist technology can be, but also how it can be done” (Snelting et al 2018, 03’00’’) emphasising praxis and tool-making. Elaborating on feminist servers, Snelting continues that these are thought of through feminist lenses and ethics of care perspectives, reflecting on the relation between “service” and “server” (13’08’’). If we are to move towards more reflexive and inclusive digital tools, feminist servers can be a key node in the network, visualising the importance of servers as spaces and as actors.

But outside of the niche spaces of new media art and culture, rethinking the spatial and social implications of servers and data remains urgent for the present and future online. Alternative media or mainstream — either will be shaped with and through data and technology imaginaries. Contributions such as Clark-Parsons and Lingel’s article and objects like A Feminist Server Manifesto show how it is not only possible but important to work towards reparative, feminist approaches to research both methodologically and tool-wise. Embracing situated perspectives as opposed to a “seemingly neutral” mechanism, and “elevate emotion and embodiment” (D’Ignazio and F. Klein 2020) remain crucial tools. Data feminist imaginaries construct feminist data, by avoiding “the view from an imaginary and impossible standpoint that does not and cannot exist.” (D’Ignazio and F. Klein 2020). Perhaps only then, critical gestures online can really emerge, and the feminist server can materialise thanks to the “communities that care enough for her in order to make her exist” (“Feminist Server Manifesto” 2013).

Bibliography:

‘A Feminist Server Manifesto – SystersWiki’. 2013. Accessed 27 September 2021. https://hub.xpub.nl/systers/mediawiki/index.php?title=A_Feminist_Server_Manifesto.

Clark-Parsons, Rosemary, and Lingel, Jessa. 2020. ‘Margins as Methods, Margins as Ethics: A Feminist

Framework for Studying Online Alterity’. Social Media + Society 6 (1): 205630512091399. https://doi.org/

10.1177/2056305120913994.

D’Ignazio, Catherine and F. Klein, Lauren. 2020. Data Feminism. Ideas Series. Cambridge, Massachusetts:

The MIT Press.

Ensmenger, Nathan. 2015. ‘Beards, Sandals, and Other Signs of Rugged Individualism: Masculine Culture

within the Computing Professions’. Osiris 30 (1): 38–65. https://doi.org/10.1086/682955.

Foster, Ellen K. 2020. ‘Histories of Technology Culture Manifestos: Their Function in Shaping Technology

Cultures and Practices’. Digital Culture & Society 6 (1): 57–84. https://doi.org/10.14361/dcs-2020-0104.

Haraway, Donna. 1991. Simians, Cyborgs, and Women : The Reinvention of Nature. New York: Routledge. 149—181.

hooks, bell. 1989. ‘Choosing the Margin as a Space of Radical Openness’. Framework: The Journal of

Cinema and Media, no. 36: 15–23. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44111660.

Snelting, Femke, Spideralex, and Sollfrank, Cornelia. 2018. Forms of Ongoingness: Interview with Femke

Snelting and Spideralex. Video. https://medienarchiv.zhdk.ch/entries/fcdf4e3e-5bf0-4a8e-9467-

e43657f01257