Hiding Behind a Choice: The New Digital Divide the ‘Find My’ App Shows Us

In the age of data capitalism in which our sensitive information is of economic value, it is important to critically examine Big Data and the practices that are used to collect it. In their work ‘Critical Questions for Big Data: Provocations for a Cultural, Technological, and Scholarly Phenomenon’ Danah Boyd and Kate Crawford (2012) state that “Big Data is seen as a troubling manifestation of Big Brother, enabling invasions of privacy, decreased civil freedoms, and increased state and corporate control”. This eludes to the collection and analysis of data as a form of surveillance, also called dataveillance, which is done by companies to fulfill their data imperative (Sadowski, 2019). This idea of companies in this way surveilling people has often been criticized within academia (Boyd & Crawford, 2012); (Kitchin, 2014); (Lupton & Micheal, 2017); (Shilton, 2009). As Boyd and Crawford state, it is still important to keep critically examining data on its meaning, who gets access, how it is analyzed. With this in mind, I want to critically examine the ‘Find My’ app which is owned by Apple using Boyd and Crawford’s article as the framework.

Behind the choice

The Find My app is an app where you can share your real-time location with anyone of the user’s choosing. Provided that the other user also uses the app. The app can also be used to find a person’s missing Apple device. The app’s function to track a friend’s or family’s location is marketed by Apple as “keeping up with friends and family” (Apple, 2021). It seems to be marketed as a kind of social surveillance. Social surveillance means that a person uses social media to see what people in their lives are ‘up to’ (Marwick, 2012). Although one might be uncomfortable at the thought of people constantly knowing their location, the choice of who gets to know their location might offer comfort to the users of the app (Consolvo et al., 2005).

I would argue, however, that Apple hides behind the affordance of choice. Perhaps giving their users a false sense of security. On a podcast called ‘Why’d You Push That Button?’ Russell Brandom, a senior reporter at The Verge, criticizes the Find My app by saying:

“I guess I would just start from the premise that you believe you’re making these choices of your own free will, but in fact, you’re operating in a system that’s been created by corporations to extract information out of you that can be used to target advertising” (Carman, 2017).

This criticism is arguably a fair one. The market sees an opportunity in Big Data for targeted advertisements according to Boyd and Crawford (2012), but as they further state in their article, just because the data is accessible does not mean it is ethical.

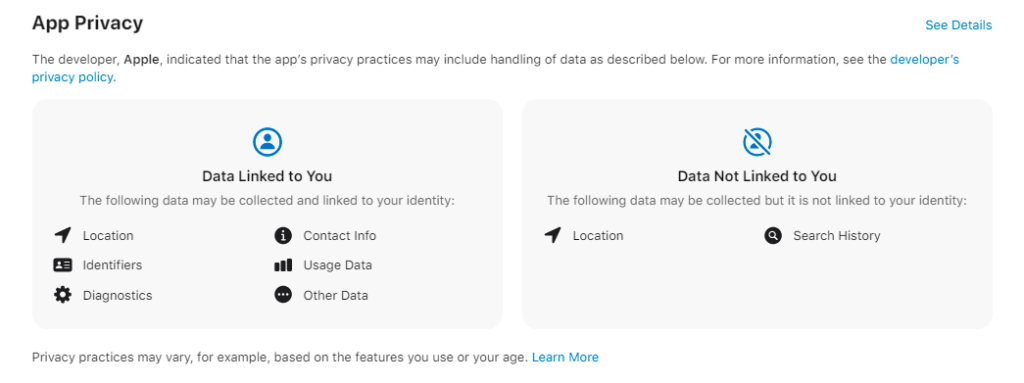

Location data can be classified as sensitive personal data considering it gives insight into a person’s everyday life. This also at the same time makes this data more valuable to companies. In Apple’s app store privacy labels are placed on apps in which one can see what kind of data the app collects and how that data might be used. This is divided into three categories. The first is data that is used to track you, the second is data linked to you, and the third is data not linked to you. In figure 1, the labels on the Find My app can be seen. There is no data collected used to track you according to the label, which seems like good news. However, there is still a lot to say about the ‘data linked to you’ category. The data that is collected under this category can be tied to your identity, like your account. (Apple Support, 2021). With this data, Apple is not supposed to be able to track you across apps. The question arises if this is true when an Apple account can be used for a variety of apps.

The New Digital Divide

Although these labels seem like a move forward in protecting user privacy by providing them more knowledge on what is being done with their data, there is still a relatively large discrepancy in who actually holds the most control over the user data. As Boyd and Crawford (2012) explain in their article Big Data has created new digital divides. As they point out, only social media companies have full access to the data. They also argue that not only in access these companies hold more control but also in knowledge. It is also pointed out by Boyd and Crawford that this divide in knowledge is also gendered. Computer scientists (of which there are more males) working for social media companies are more knowledgeable in the meaning and handling processes of that data. Which in turn also gives them more power over an app user that is likely to not have that kind of knowledge. Users usually do not read the privacy policies, and when they do, they are likely not to understand them (Solove, 2013). So the effort by Apple to put these labels in their app store, albeit with possibly good intentions, might not reach the user in the way it is supposed to.

The Future

Questions arise out of this new digital divide. In my opinion, the most important one is the question of how we are going to bridge this divide. Of course, things like an increase in informational literacy among the public (Van Dijck, 2010) might help in terms of the divide in knowledge. The processes of gathering user data and handling that data by companies are still a black box to most, which limits the control one might want over their data. Actions through legislation to make the box more transparent are good steps forward. We are still trying to keep up with how fast the realm of data is developing and finding out what these consequences are, hopefully one day we will be able to catch up.

References

Apple. 2021. “ICloud – Find My.”. https://www.apple.com/icloud/find-my/.

Apple Support. 2021. “About Privacy Information on the App Store and the Choices You Have to Control Your Data.”. https://support.apple.com/en-us/HT211970.

Boyd, d. & Crawford, K., 2012. Critical Questions for Big Data. Information, Communication & Society, 15(5), pp. 662–679.

Carman, Ashley. 2017. “Why Do You Share Your Location?” The Verge. https://www.theverge.com/2017/12/19/16792336/location-sharing-apps-privacy-whyd-you-push-that-button-podcast.

Consolvo, S., Smith, I., Matthews, T., LaMarca, A., Tabert, J., and Powledge, P. 2005. Location disclosure to social relations: why, when, & what people want to share. Proc. CHI 2005, ACM Press, 81–90.

Kitchin, Rob. 2014. The Data Revolution: Big Data, Open Data, Data Infrastructures & Their Consequences. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Lupton, Deborah, and Mike Michael. 2017. “‘Depends on Who’s Got the Data’: Public Understandings of Personal Digital Dataveillance.” Surveillance & Society 15, no. 2 (n.d.): 254–68. doi:10.24908/SS.V15I2.6332.

Marwick, Alice. 2012. The public domain: social surveillance in everyday life. Surveillance & Society 9 (4):378-393. doi:10.24908/SS.V9I4.4342

Sadowski, Jathan. 2019. “When data is capital: Datafication, accumulation, and extraction.” Big Data & Society 6.1: 2053951718820549.

Shilton, K. 2009. Four billion little brothers? Privacy, mobile phones, and ubiquitous data collection. Communications of the ACM, 52, 48-53.

Solove, D. 2013. ‘Privacy management and the consent dilemma’, Harvard Law Review, 126: 1880-903

Van Dijck, José. 2010. “Search Engines and the Production of Academic Knowledge.” International Journal of Cultural Studies 13 (6): 574–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367877910376582