The Academic Value of Bottom-up Knowledge Produced by Marginalized Groups: The Relevance of Instagram Infographics for Ethical Terminology Frameworks

Language is power. Rosemary Clark-Parson and Jessa Lingel explain that when studying online alterity in an ethical way, it is important to critically reflect on the power politics behind the terminology internet researchers use to describe the groups they study[1]. Instagram infographics, a tool where marginalized groups share simplified content about their identity and political issues, are not only a way to inform peers, but also a relevant source for researchers when creating an ethical terminology framework. Therefore I propose this form of bottom-up knowledge production is added to the margins-as-methods approach – using the bisexual identity and experience as a case study[2].

Definition Power

Michel Foucault explains in The Order of Things that human language is a demonstration of the human mind which slowly changes through time and through cultural exchange, just like the cycle of human beliefs. Language and definitions are present in all aspects of our society, and therefore it is important to investigate the underlying power structures in defining accepted terminologies[3].

It is important that researchers are aware of this. Clark-Parson and Lingel explain that respect for the group you are researching requires thoughtful representations of them, because researchers have a final say in how participants are portrayed[4]. Moreover, the labels that are used can have repercussions for the well-being of the people that are studied[5]. Stigmas have tactical consequences for marginalized groups and in order to address these, ethical definitions are needed.

Infographics and the Bisexual Discourse

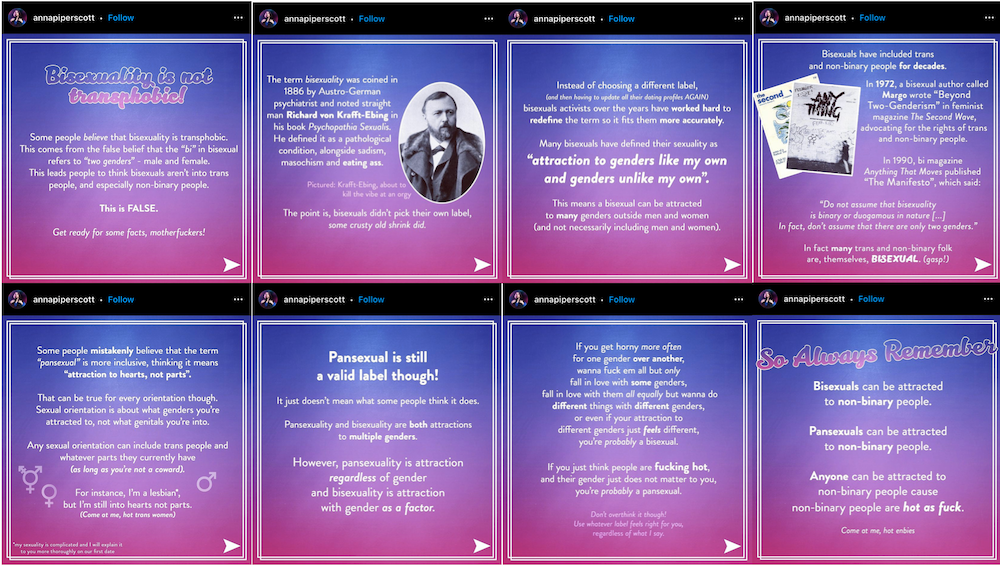

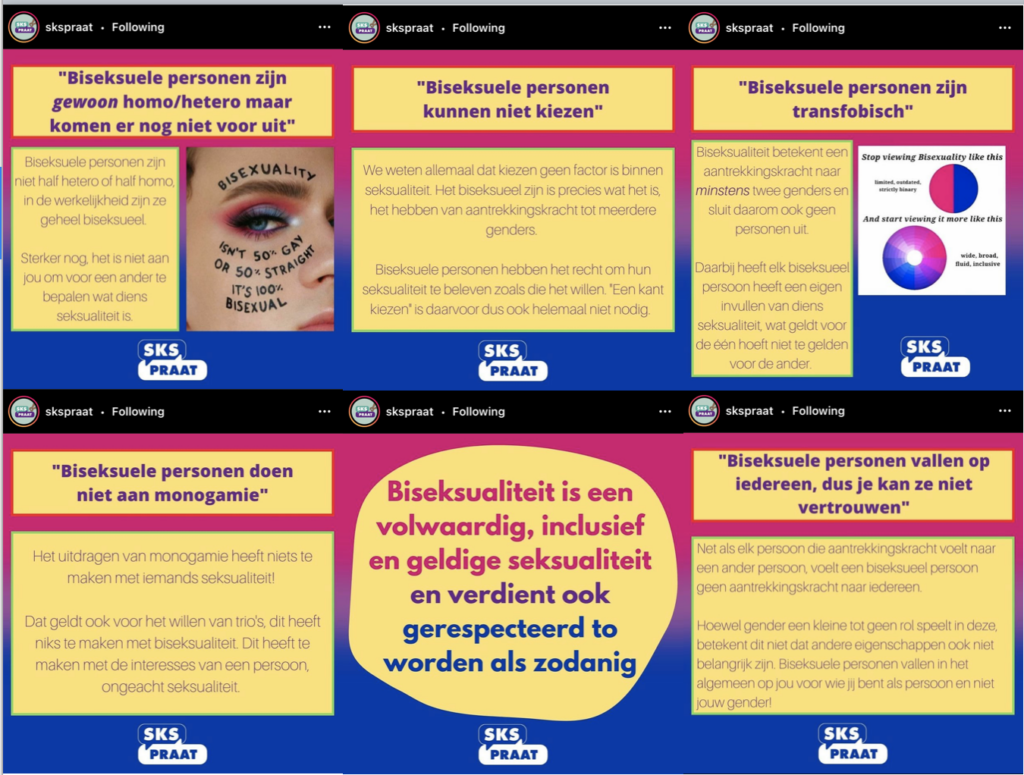

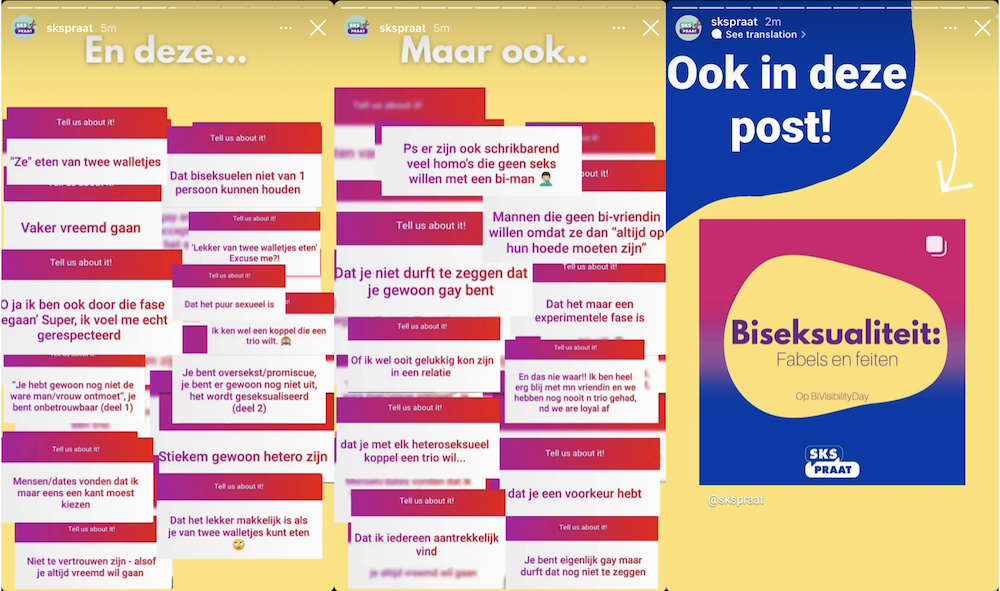

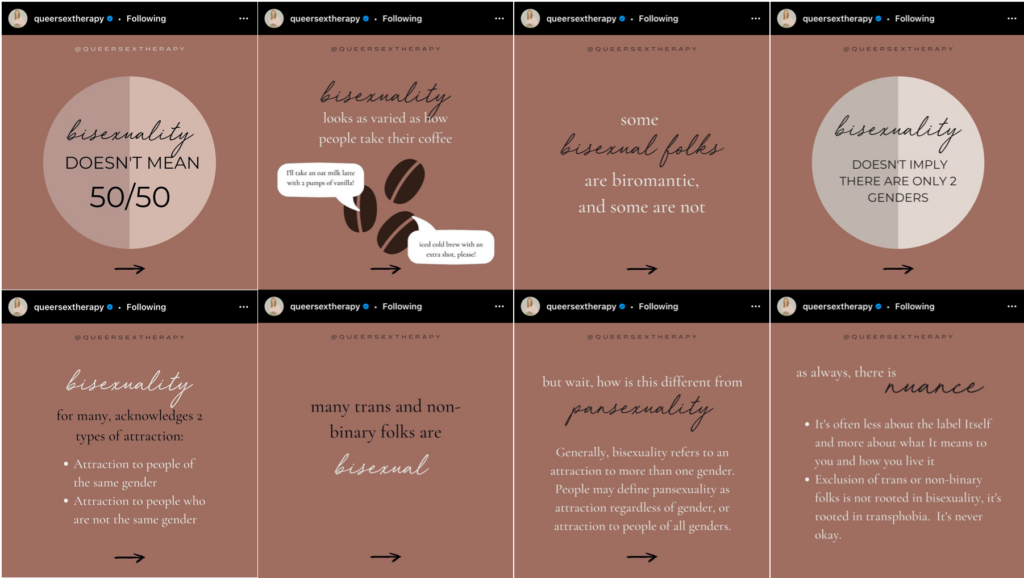

The bisexual identity, with all its ambiguities and stereotypes[6] is a perfect example to address this political need for defining. Through Instagram infographics (II), the bisexual community is currently informing peers and having discussions about their identity.

Hannah Berman contextualizes II and states that this trend, that emerged in the wake of George Floyd’s murder, should receive more attention. According to her, II are uniquely capable of transmitting information and are therefore a powerful political tool. Owen Jones, in his article about millennials and generation Z turning their backs on capitalism, illustrates that political information being shared in a simplified way on social media such as Instagram[7] has opened users’ eyes about political issues such as race, identity and class, of which II, that usually consist of texts and slogans that are presented in an aesthetically pleasing way, are a perfect example. The infographic has been democratized, because according to Berman, anyone with an Internet connection and basic understanding of free editing tools has the capacity to create and widely share information.

Bisexual people have been practicing this and consequentially they are becoming a direct agent in defining the discourse around their existence. As Audre Lord says, “visibly which makes us most vulnerable is that which also is the source of our greatest strength” and to use the power of language is to reclaim it; to “define ourselves, name ourselves, and speak for ourselves, instead of being defined and spoken for by others”[8].

Fig. 1: Infographic by @annapiperscott discussing the incorrect believe that bisexual people are transphobic and the ontological difference between bisexuality and pansexuality.

Fig. 2.1: Infographic in Dutch by @skspraat discussing incorrect assumptions about bisexual people, such as them not being able to be monogamous, to choose between genders and their sexuality being a phase, based on the input of their followers (see Fig 2.2).

Fig. 2.2: Stories in Dutch by @skspraat sharing the input they received from their followers about incorrect assumptions about bisexual people, which resulted in an infographic (see Fig 2.1).

Fig. 3: Infographic by @queersextherapy about how bisexuality does not imply that there are only two genders and that binary people and trans people can be bisexual, among other subjects.

Fig. 4: Infographics by @mattixv about the different types of attraction that are possible within bisexuality and different stereotypes regarding men and women that are bisexual.

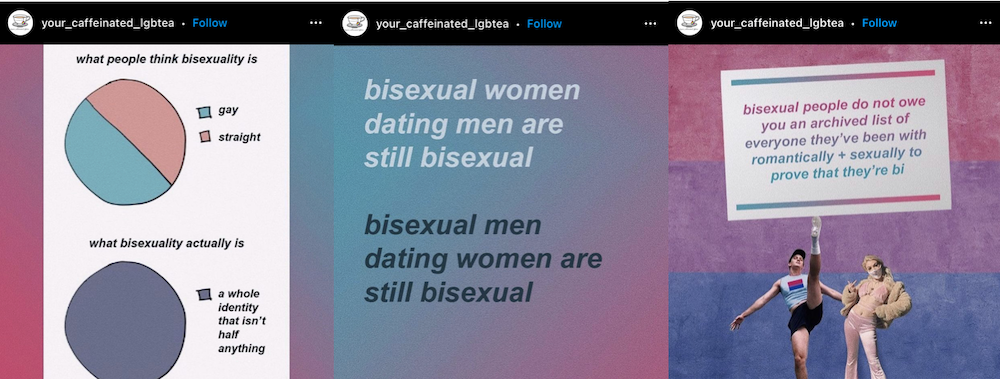

Fig. 5: Infographics by @your_caffinated_lgbtea about the bisexual identity being a valid autonomous identity that does not need to be proven with one’s history of partners.

Fig. 6: Infographics by @lekkerblijvenlikken about bisexuality not being dependent on one’s current partner.

The Relevance of Bottom-Up Knowledge Production on Instagram

II are not just relevant for the education of peers, but also have academic value for researchers when composing an ethical terminology framework, and therefore I would like to propose that they be added to the margins-as-methods approach.

Firstly, because this kind of bottom-up knowledge production should be taken seriously in an academic context. Anahita Neghabat states that mainstream media shape public discourse and (re)produce hegemonic, often sexist, racist, classist or otherwise marginalizing violent views, masked by their veil of neutrality[9]. II, similar to memes, can be used to intervene in oppressive public discourse, because they are simple, reach a huge audience, yet also stimulate critical thinking[10]. Because of the DIY aesthetic, it allows marginalized groups to create alternative representations[11]. In this way, II reject the logic of exclusive, elitist, top-down knowledge production[12] and give space for a bottom-up approach in the context of participatory internet platforms that complicate the distribution of media power[13]. In a similar way, I propose that researchers start taking these narratives just as seriously as peer reviewed sources. Even Jose van Dijk does not question the authority[14] of the peer reviewed journal when discussing the way knowledge is produced, even though Richard Smiths points out that as a method it is slow, expensive, inconsistent and is full of bias and power abuse[15]. II are a great form of what Clark-Parsons and Lingel call participatory knowledge-building practices[16].

However, as Bergman points out, II are a limited method of sharing information. She explains that because they rely on being shared widely, the information is usually simplified into eye-catching snippets, losing important context, which can lead to dangerous misunderstandings. She also states that reach and shareability seem to be more important than the reliability. However, when infographics have a reputable cited source and when researchers have a critical attitude, as Bergman concludes, infographics can be a great starting point for ethical terminology frameworks in addition to other methods.

Secondly, because II are publicly available and are meant to be spread. Clark-Parsons and Lingel mention that researchers lurking around unnoticed during the data collection process can be a form of a power imbalance between the researcher and researched[17]. In the case of II no ethical questions in this context have to be raised.

Finally, they should be added because using II as a source does not require emotional labor from the participants being researched. Focus groups are be valuable, as they are help researchers to rely on participants to provide the best vocabulary for describing their identities and collaborating with participants can shed a light on complex processes that might otherwise remain unstudied, as Clark-Parsons and Lingel point out[18]. However, asking participants to relive deeply personal experiences and potential trauma and abuse[19] can be avoided when using II that are already out there.

Conclusion

To conclude, the bottom up knowledge being produced in the form of Instagram infographics by marginalized groups, such as bisexual people, is a relevant source for researchers when composing an ethical terminology framework. However, in addition, the power structures that are in place within Instagram should be studied, in the context of platform studies and by looking at the platform’s affordances and algorithms. This profit driven platform disadvantages certain marginalized groups and progressive voices, such as sex workers[20] and activists who speak out for the freedom of Palestine[21], by limiting their reach or blocking them from the platform entirely. While Instagram is being used as a tool by marginalized groups to define their own discourses, it also limits the way in which they can do so – which is important to examine in future research.

Works cited

@annapiperscot, “It’s Bisexual Visibility Day”, Instagram photo, September 23, 2020, https://www.instagram.com/p/CFde8guDl2p/.

Berman, Hannah, “Should We Trust Instagram Infographics? How the Infographics Recent Rise in Instagram Popularity has Changes the Art Form, and What We Should Be Doing About It,” Medium.com, July 28, 2020, https://medium.com/age-of-awareness/should-we-trust-instagram-infographics-f80f04e1549e.

Clark-Parsons, Rosemary, and Jessa Lingel. 2020. “Margins as Methods, Margins as Ethics: A Feminist Framework for Studying Online Alterity.” Social Media+ Society 6 (1): 2056305120913994. https://doi-org.proxy.library.uu.nl/10.1177%2F2056305120913994.

Dawson, Brit, “Instagram’s Problem with Sex Workers is Nothing New,” Dazeddigital.com, December 24, 2020, https://www.dazeddigital.com/science-tech/article/51515/1/instagram-problem-with-sex-workers-is-nothing-new-censorship.

Van Dijck, José. 2010. “Search Engines and the Production of Academic Knowledge.” International Journal of Cultural Studies 13 (6): 574–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367877910376582

Foucault, Michel. The Order of Things. London and New York: Routledge Classics: 2002.

Jones, Women, “Eat the Rich! Why Millennials and Generaztion Z Have Turned Their Backs on Capitalism,” Theguardian.com, September 20, 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2021/sep/20/eat-the-rich-why-millennials-and-generation-z-have-turned-their-backs-on-capitalism.

@landpalastine, “Are You Having Problems with Your Instagram/TikTok Account when Posting or Engaging with Palestinian Related Content,” Instagram photo, September 18, 2021, https://www.instagram.com/p/CT9r7N_Nx-U/?utm_medium=copy_link.

@lekkerblijvenlikken, “I Am Bisexual”, Instagram photo, September 23, 2021, https://www.instagram.com/p/CUKs4ezI451/.

Lorde, Aurde. Your Silence Will Not Protect You. Mardrid: Silver Press, 2017.

@mattixv, “Happy Bi Week,” Instagram photo, September 18, 2021, https://www.instagram.com/p/CT8OLBsMEsX/.

Neghabat, Anahita. “Ibiza Austrian Memes: Reflections on Reclaiming Political Discourse through Memes.” In Critical Meme Reader: Global Mutations of the Viral Image, edited by Chloë Arkenbout, Jack Wilson and Daniel de Zeeuw, 130-142. Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, 2021.

@queersextherapy, “Bisexuality Does Not mean 50/50”, Instagram photo, September 23, 2021, https://www.instagram.com/p/CUKn8hJLY3i/.

@skspraat, “Biseksualiteit: Fabels en Feiten”, Instagram photo, September 23, 2021, https://www.instagram.com/p/CUKl7hEoRie/.

@skspraat, “Biseksualiteit: Fabels en Feiten”, Instagram Stories, captured on September 24, 2021.

Smith, Richard. “Peer Review: a Flawed Process at the Heart of Science and Journals.” Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, no. 99 (April 2006): 178-182.

“Wij VS Zij #24 – Wie Bepaalt het Gesprek? Over Machtstructuren in Taal, Cultuur en Wie een Podium Krijgt Binnen Beleid, Media en Culturele Organisaties,” OneWorld.nl, accessed October 2, 2021, https://www.oneworld.nl/events/wij-vs-zij-24-wie-bepaalt-het-gesprek/.

@your_caffeinated_lgbtea, “Happy Bi Pride”, Instagram photo, September 18, 2021, https://www.instagram.com/p/CT8d4BprnUD/.

[1] Clark-Parsons, Rosemary, and Jessa Lingel. 2020. “Margins as Methods, Margins as Ethics: A Feminist Framework for Studying Online Alterity.” Social Media+ Society 6 (1): 2056305120913994. https://doi-org.proxy.library.uu.nl/10.1177%2F2056305120913994: 2.

[2] It is important to note that I am part of the bisexual community and therefor have emphatical knowledge on the subject, but as a researcher I am also biased because of personal experience. As Clark-Parsons and Lingel point out, it is important to acknowledge the researcher’s perspective and their situated knowledge (7). The analysis that will follow is also applicable to other marginalized groups that share infographics in a similar way. Studying this phenomenon with an intersectional approach, connecting these groups, would be desirable in the future.

[3] “Wij VS Zij #24 – Wie Bepaalt het Gesprek? Over Machtstructuren in Taal, Cultuur en Wie een Podium Krijgt Binnen Beleid, Media en Culturele Organisaties,” OneWorld.nl, accessed October 2, 2021, https://www.oneworld.nl/events/wij-vs-zij-24-wie-bepaalt-het-gesprek/.

[4] Clark-Parsons, Rosemary, and Jessa Lingel. 2020. “Margins as Methods, Margins as Ethics: A Feminist Framework for Studying Online Alterity.” Social Media+ Society 6 (1): 2056305120913994. https://doi-org.proxy.library.uu.nl/10.1177%2F2056305120913994: 6.

[5]Clark-Parsons, Rosemary, and Jessa Lingel. 2020. “Margins as Methods, Margins as Ethics: A Feminist Framework for Studying Online Alterity.” Social Media+ Society 6 (1): 2056305120913994. https://doi-org.proxy.library.uu.nl/10.1177%2F2056305120913994: 6.

[6] See Fig. 1-6 for concrete examples.

[7] This article also mentions other social media platforms such as TikTik, Twitter and Tumblr. Researching these platforms, in addition to Instagram, in the context of spreading simplified information in the future would be desired.

[8]Lorde, Aurde. Your Silence Will Not Protect You. Mardrid: Silver Press, 2017.

[9] Neghabat, Anahita. “Ibiza Austrian Memes: Reflections on Reclaiming Political Discourse through Memes.” In Critical Meme Reader: Global Mutations of the Viral Image, edited by Chloë Arkenbout, Jack Wilson and Daniel de Zeeuw, 130-142. Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, 2021: 133-137.

[10] Neghabat, Anahita. “Ibiza Austrian Memes: Reflections on Reclaiming Political Discourse through Memes.” In Critical Meme Reader: Global Mutations of the Viral Image, edited by Chloë Arkenbout, Jack Wilson and Daniel de Zeeuw, 130-142. Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, 2021: 133-137.

[11] Neghabat, Anahita. “Ibiza Austrian Memes: Reflections on Reclaiming Political Discourse through Memes.” In Critical Meme Reader: Global Mutations of the Viral Image, edited by Chloë Arkenbout, Jack Wilson and Daniel de Zeeuw, 130-142. Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, 2021: 133-137.

[12] Neghabat, Anahita. “Ibiza Austrian Memes: Reflections on Reclaiming Political Discourse through Memes.” In Critical Meme Reader: Global Mutations of the Viral Image, edited by Chloë Arkenbout, Jack Wilson and Daniel de Zeeuw, 130-142. Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, 2021: 138.

[13] Clark-Parsons, Rosemary, and Jessa Lingel. 2020. “Margins as Methods, Margins as Ethics: A Feminist Framework for Studying Online Alterity.” Social Media+ Society 6 (1): 2056305120913994. https://doi-org.proxy.library.uu.nl/10.1177%2F2056305120913994: 4.

[14] Van Dijck, José. 2010. “Search Engines and the Production of Academic Knowledge.” International Journal of Cultural Studies 13 (6): 574–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367877910376582.

[15] Smith, Richard. “Peer Review: a Flawed Process at the Heart of Science and Journals.” Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, no. 99 (April 2006): 179-180.

[16] Clark-Parsons, Rosemary, and Jessa Lingel. 2020. “Margins as Methods, Margins as Ethics: A Feminist Framework for Studying Online Alterity.” Social Media+ Society 6 (1): 2056305120913994. https://doi-org.proxy.library.uu.nl/10.1177%2F2056305120913994: 5.

[17] Clark-Parsons, Rosemary, and Jessa Lingel. 2020. “Margins as Methods, Margins as Ethics: A Feminist Framework for Studying Online Alterity.” Social Media+ Society 6 (1): 2056305120913994. https://doi-org.proxy.library.uu.nl/10.1177%2F2056305120913994: 5.

[18] Clark-Parsons, Rosemary, and Jessa Lingel. 2020. “Margins as Methods, Margins as Ethics: A Feminist Framework for Studying Online Alterity.” Social Media+ Society 6 (1): 2056305120913994. https://doi-org.proxy.library.uu.nl/10.1177%2F2056305120913994: 6.

[19] Clark-Parsons, Rosemary, and Jessa Lingel. 2020. “Margins as Methods, Margins as Ethics: A Feminist Framework for Studying Online Alterity.” Social Media+ Society 6 (1): 2056305120913994. https://doi-org.proxy.library.uu.nl/10.1177%2F2056305120913994: 5.

[20] Dawson, Brit, “Instagram’s Problem with Sex Workers is Nothing New,” Dazeddigital.com, December 24, 2020, https://www.dazeddigital.com/science-tech/article/51515/1/instagram-problem-with-sex-workers-is-nothing-new-censorship.

[21] @landpalastine, “Are You Having Problems with Your Instagram/TikTok Account when Posting or Engaging with Palestinian Related Content,” Instagram photo, September 18, 2021, https://www.instagram.com/p/CT9r7N_Nx-U/?utm_medium=copy_link.