From Field Recordings to A Future Recipe: Sensing Blockchain as An Infrastructure in China

The idea of using blockchain to revamp cryptocurrency transaction and data storage is no longer exciting. After years of test and development, blockchain has been applied to different aspects of our society, including fields like finance, public health, agriculture and government administration.

Blockchain, an intangible infrastructure

The recently published “Outline of China’s 14th Five-Year Plan (2021-2025) and Vision 2035” (2021) hastily inculcates a sense of common belief that blockchain is becoming a new information infrastructure in China, and this belief is permeating Chinese peoples’ everyday life. Nevertheless, from the government’s recent crackdown on bitcoin mining and cryptocurrency to ‘blockchain chickens’ and ‘blockchain health code’ on food delivery apps and WeChat, for those who are not acquainted with the technology behind, it seems that blockchain is only latent in myths of overnight bitcoin wealth or existing as a buzzword in the digital world.

Blockchain is not as ubiquitous as transport, electricity or the Internet infrastructures in daily life, this shared cryptographic register enables immutable storage and tamper-resistant ledger “in a permanent and verifiable manner without the need for any intermediary or central authority” (Husain, Franklin, and Roep 2020). However, when blockchain is authoritatively reinvented as an infrastructure, one cannot help but wonder what blockchain would do to the society and how it would function “between the material and immaterial, the empirical and theoretical, the place-bound and the placeless” (Mattern 2013).

To answer these questions, the first step is to sense the existence of blockchain as an intangible but perceptible infrastructure. Mattern (2013) points out that infrastructure can easily switch between figure and ground as it is the “most sophisticated technological artifacts” (Graham and Marvin 1996 cited in Star and Bowker 2006) that “runs ‘underneath’ actual structures” (Star and Bowker 2006). In addition, infrastructural systems like blockchain “are not necessarily static; they are mutable, portable, transient” (Mattern 2013). To pin down blockchain as a new infrastructure that does not “easily translate into more conventional, or visual, graph formats” (Bogost 2012 cited in Mattern 2013), new ways are required to “make some process perceptible” (Mattern 2013).

Zomia field recording and bitcoin mining

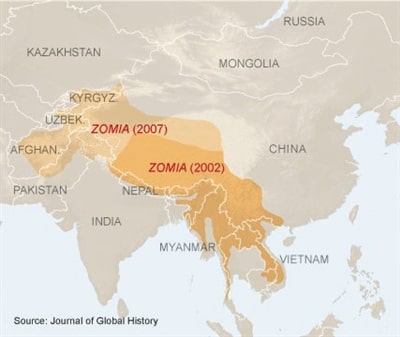

China used to be home to some of the biggest cryptocurrency and blockchain firms (Wang 2020a) because of its cheap and abundant hydropower in southwest mountain regions. Bitcoin mining farms in southwestern China would move from one river valley to another according to the dry and wet season of rivers because of the dependency on hydroelectricity. Artist Liu Chuang incidentally found the overlap between his route of a field research on Chinese ethnic minorities in Zomia region and the route of bitcoin farm’s seasonal relocation. In Liu Chuang’s three-channel video Bitcoin Mining and Field Recordings of Ethnic Minorities (2018), the artist interweaves field recordings, ethnographic archives, narration, footages, film clips and machine noise, “tracing the material and immaterial lines of power that are used to conquer people and territories, and to generate material and immaterial profit”(2019).

By utilizing different forms of media and juxtaposing seemingly irrelated objects, the artist questions the technology and infrastructure of bitcoin and blockchain from three main perspectives: Firstly, in an attempt to indicate that blockchain is actually neither “wireless” (Mackenzie 2010 cited in Mattern 2013) nor “chipsetless”, Liu Chuang juxtaposes video footages of hydroelectricity power station and the sign of bitcoin. In addition, the video is accompanied by noise of fans and hard disks inside computers recorded in bitcoin mining farms, by building nuanced connections between hydroelectricity and blockchain technology, the artist implies that blockchain is an infrastructure like electricity and it is also embedded in and attached to infrastructures such as electricity and the Internet.

Second, in this video, the voiceover narration of bitcoin and blockchain was recorded in Muya language, a patois spoken by only ten thousand Tibetan and Qiang minorities in Zombia regions. To understand the second layer of the artist’s thinking, the ethos of Zomia will be explained.

Zomia is a region rejecting the “mighty lowland states that are seen as defining Asia” (Scott 2009, p179), the once called ‘hill people’ in Zomia have “remained culturally aloof from the traditional centers of power and the pull of empires” (2009) in thousands of years because of their “anti-authoritarian tendencies” (Scott 2009, p179). Being similar to Zomia, blockchain is also endowed with the ethos of decentralization and anti-authoritarian, and interestingly, the distribution of bitcoin mining farms and the Zomia region within China somehow overlap. This overlap also connotes the question of whether blockchain can keep the state at arm’s length as what Zomia has been doing for ages. Star and Bowker (2006) argues that “frequently a technical innovation must be accompanied by an organizational innovation in order to work”, therefore, can blockchain find a way out of centralized, authoritarian system, or instead, will it become a de-decentralized “Techno-Leviathan”(Scott cited in Husain, Franklin, and Roep 2020) with Chinese characters? This is the ultimate question the artist wants to ask throughout the video.

Last but not least, the artist also displayed what Star and Bowker (2006) refers to as the ‘information rich’ and the ‘information poor’. By taking fiat money (a coin) on a bullet train trip, Liu Chuang implies that bitcoin and electricity are transited over space, from disadvantaged, rural southwest villages to megacities in the east of China through ‘invisible’ infrastructures; and the rural are paving way for urban development and capital accumulation. This artwork was created in the year of 2018, however, the query on decentralized blockchain as an infrastructure, and the inequality behind blockchain are currently highlighted in China’s society. In his work, Liu Chuang distinctively creates his “own infrastructures” (Mattern 2013) of looking at the connections between technology and human society. By generating the intertextuality between different materials, methods and media, the artist pushes the audience “to question, and to be more self-reflexive” (Mattern 2013) when facing with a new infrastructure–blockchain.

Chickens wear FitBit and a future recipe

In contrast to Liu Chuang’s ethnographic perspectives of thinking, Xiaowei Wang’s research on blockchain as an infrastructure in agriculture is more playful and microcosmic. Morevoer, Wang’s study also to some extent responds to the questions Liu Chuang raised before. In an effort to understand the concept of ‘blockchain chicken’ (also known as ‘Gogo Chicken’) amid all the marketing hype, she visited ‘blockchain chicken farms’ located in Sanqiao village in Guizhou (also in Zomia region), one of the impoverished villages. The blockchain chicken farms are invested by both private tech firms and the government. As Wang describes, Gogo Chicken farm “stored the information of each free-range chicken on a private blockchain, with each chicken’s weight, date slaughtered and number of steps taken in the pasture on the blockchain”(Wang 2020a). These ‘FitBit-equipped’ chickens slake Chinese wealthy people and mid class’ hunger of healthy food since there are a lot of concerns over food-safety issues in China. This fact re-emphasizes the gap between both the information and the socioecnomic rich and poor”.

Wang argues that blockchain is similar to an authoritarian regime, they both underly the assumption that from famers to merchants and firms “people cannot be trusted in a free market, and bad actors are intrinsic to a social system”(Wang 2020b). She goes one step further quoting Karissa McKelvey’s statement “blockchain governance is not unbiased or neutral. It’s just shifting bureaucratic roles to more technical roles”(Wang 2020b). Ironically, according to Wang, the advanced blockchain technology did not observably increase famer’s incomes as the overheads of raising chickens also increased. When asked about if they like blockchain, the Gogo Chicken farmers asked back “what is blockchain?”

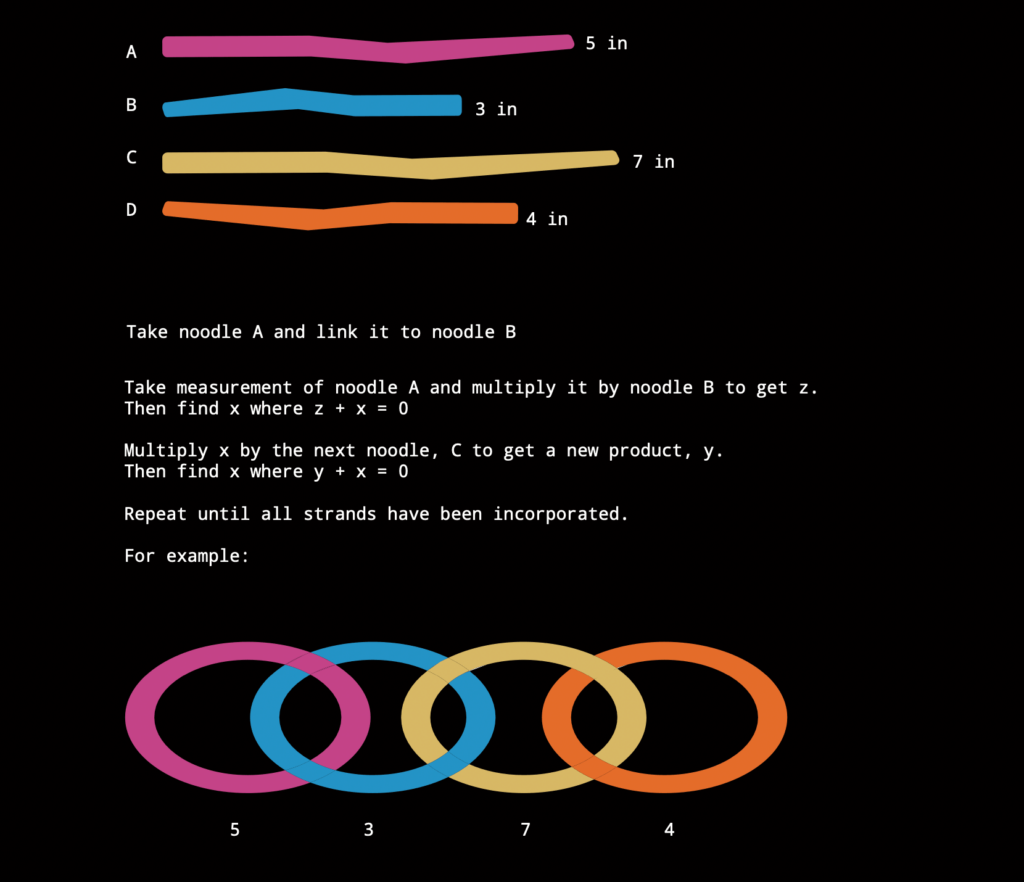

Intrigued by the experience in Guizhou, in the article Future Recipes, Wang (2020a) fabricates a short story as a travesty to the socioeconomic inequality and bureaucratic character behind blockchain as infrastructure in China. In the story, a farmer’s wife who owns a noodle stand in Guizhou “set up an Ethereum mining rig for herself through the village’s poverty alleviation fund and cheap wind power”(Wang 2020a), after opening several successful blockchain noodle shops in 2025, this woman “open sourced her recipe for blockchain noodles”(Wang 2020a).

In the apocryphal future recipe, she ingeniously illustrates the basic idea of blockchain by likening making noodles to building up blockchains, encouraging people’s willingness to understand blockchain. Liu Chuang and Xiaowei Wang’s ways of study blockchain not only generate “awareness about existing infrastructures” but also reveal “operational modes and logics” (Mattern 2013) of infrastructures. In today’s context, their concerns are still not misplaced. From blockchain chickens to blockchain health code, where would blockchain take us? To a ‘nanny state’ composed of machines? Or probably we should borrow some wisdoms from the ancient Zomia.

Work cited:

Academic source:

Husain, SO, Franklin, A, and Roep, D 2020, “The Political Imaginaries of Blockchain Projects: Discerning the Expressions of an Emerging Ecosystem.” Sustainability Science 15(2): 379–94.

Mattern, S 2013, “Infrastructural Tourism.” Places Journal (2013). https://placesjournal.org/article/infrastructural-tourism/ (October 3, 2021).

Star SL and Bowker GC 2006, “How to Infrastructure”, Handbook of New Media, Social Shaping and Social Consequences of ICTs, SAGE Publications Ltd.

Wang, X 2020a, “Future Recipes”. In Real Time: Making Digital China, Renaud, C, Bideau, FG & Laperrouza, M (chap.10, p209-217) Presses polytechniques et universitaires romandes.

Wang, X 2020b, Blockchain Chicken Farm: And Other Stories of Tech in China’s Countryside. “E-book ISBN: 978-0-374-72125-1”

Online source:

China’s ‘two sessions’: first mention of blockchain in five-year plan boosts still-nascent industry. https://www.scmp.com/tech/policy/article/3125020/chinas-two-sessions-first-mention-blockchain-five-year-plan-boosts

White Rabbit Gallery, Media Release of Bitcoin Mining and Field Recordings of Ethnic Minorities. https://explore.dangrove.org/objects/3330

The mystery of Zomia http://archive.boston.com/bostonglobe/ideas/articles/2009/12/06/the_mystery_of_zomia/